What Is the Life Expectancy If Stage 4 Neuroendocrine Cancer Has Spread to the Liver?

- Understanding Neuroendocrine Cancer: A Complex Disease

- Why the Liver Is a Common Site of Spread

- Prognostic Factors That Affect Life Expectancy

- Symptoms That May Indicate Liver Involvement

- How Long Can You Live With Stage 4 Neuroendocrine Cancer in the Liver?

- Treatment Options for Liver Metastases in NETs

- Comparison of Treatments and Their Impact on Prognosis

- Monitoring Disease Progression and Response to Treatment

- Impact of Functional vs. Non-Functional Tumors on Prognosis

- Quality of Life Considerations in Advanced Disease

- Role of Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies

- Environmental and Lifestyle Factors in Long-Term Management

- Surgical Options and Liver Resection in Select Cases

- End-of-Life Considerations and Hospice Care

- Communicating Prognosis with Patients and Families

- Living with Stage 4 NETs and Liver Metastases

- FAQ: Stage 4 Neuroendocrine Cancer Spread to Liver — Life Expectancy and Care

Understanding Neuroendocrine Cancer: A Complex Disease

Neuroendocrine cancer (NET) originates from neuroendocrine cells, which have both nerve and hormonal functions. These tumors can develop in various organs, including the pancreas, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and rectum. Unlike many other cancers, NETs vary greatly in how aggressive they are. Some grow slowly over years, while others progress rapidly and resemble high-grade carcinomas.

The challenge with NETs lies in their diversity. Low-grade NETs may cause few symptoms for long periods, especially if they’re non-functional (i.e., not secreting hormones). High-grade or poorly differentiated NETs, however, behave more like traditional cancers, often spreading quickly and aggressively. Diagnosis requires a combination of imaging, pathology, and biochemical markers.

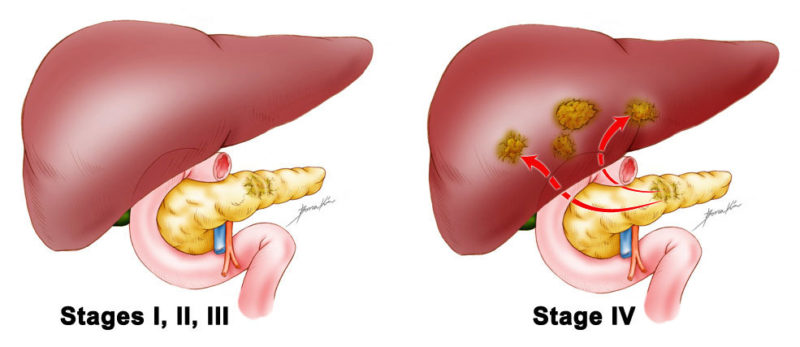

When NETs reach stage 4, it means the disease has metastasized, typically to the liver, lungs, or bones. Liver involvement is particularly common and has critical implications for prognosis and treatment. Unlike localized disease, metastatic NETs are not curable, but many patients still live for years, depending on tumor grade and burden.

Why the Liver Is a Common Site of Spread

The liver is often the first and most significant site of metastasis for neuroendocrine cancer. This happens because blood from the gastrointestinal tract flows directly to the liver through the portal vein, carrying tumor cells with it. Once there, the cells can lodge in liver tissue and begin forming metastatic lesions.

Liver metastases can remain asymptomatic for months or even years, especially in well-differentiated NETs. However, as the disease progresses, these lesions can interfere with liver function, hormone clearance, and bile drainage. In functional tumors, metastases may amplify hormone secretion, causing severe symptoms such as flushing, diarrhea, wheezing, or heart complications.

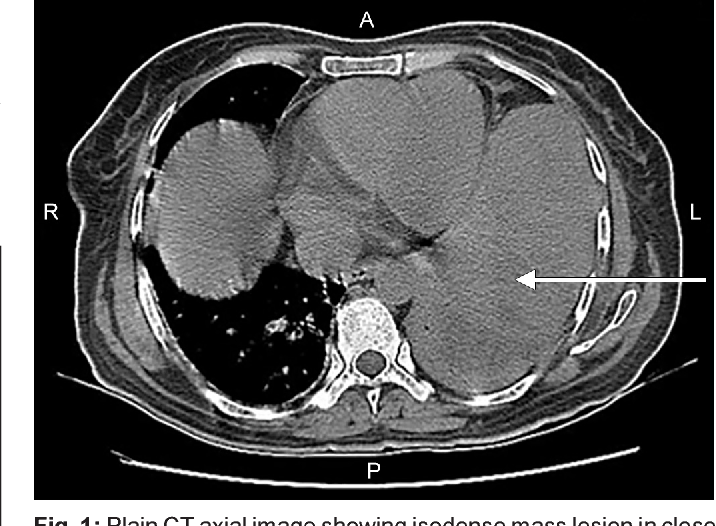

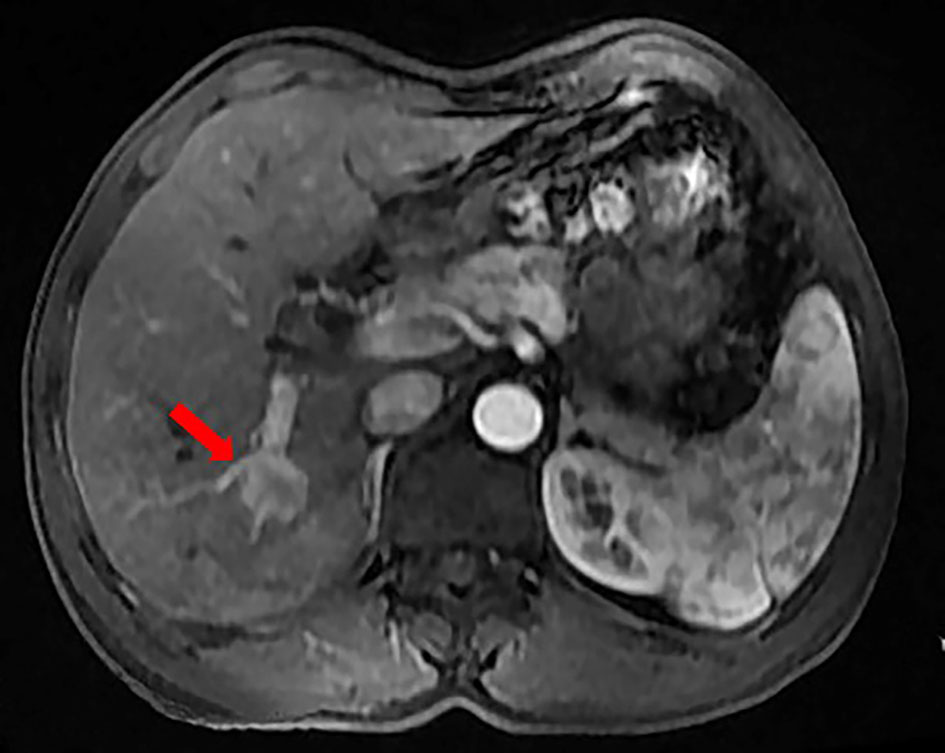

The extent and distribution of liver metastases play a central role in determining survival. Patients with fewer, localized lesions tend to live longer than those with widespread liver involvement. Imaging studies—such as contrast-enhanced MRI or Ga68 DOTATATE PET scans—help map the disease burden and guide both prognosis and treatment strategy.

Prognostic Factors That Affect Life Expectancy

Life expectancy in stage 4 NET with liver metastases is highly variable. It depends on a constellation of clinical and biological features. The most influential prognostic factor is tumor grade, determined by the Ki-67 proliferation index and mitotic rate. Low-grade tumors (G1, Ki-67 < 3%) may progress slowly and respond well to treatment, while high-grade tumors (G3, Ki-67 > 20%) are often aggressive with poorer outcomes.

Other key factors include tumor origin (pancreatic NETs often behave differently from small bowel NETs), the number and size of liver metastases, whether the disease is functional or non-functional, and the patient’s overall health. Liver function tests, chromogranin A levels, and imaging results also help estimate disease trajectory.

In large studies, median overall survival for well-differentiated NETs with liver metastases ranges from 3 to over 10 years, depending on treatment. For high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas, survival may be less than 12–18 months. These ranges highlight the importance of individualized treatment plans and realistic but hopeful counseling.

In clinical practice, discussing life expectancy is delicate and must reflect both biology and psychology—just as with hormone-related oncology cases like refusing hormone therapy for breast cancer, where decisions deeply influence survival and quality of life.

Symptoms That May Indicate Liver Involvement

When neuroendocrine tumors spread to the liver, symptoms can vary depending on tumor burden, hormonal activity, and liver function impairment. Many patients experience no symptoms at first, especially in the case of non-functional, slow-growing NETs. However, as disease progresses, several warning signs may emerge.

Fatigue is one of the earliest and most common symptoms, often mistaken for general weakness or aging. As liver metastases grow, abdominal discomfort or a sense of fullness on the right side may develop. Some patients notice weight loss, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes), or unexplained nausea.

In functional NETs—particularly those that secrete serotonin or other peptides—patients may experience carcinoid syndrome, marked by facial flushing, diarrhea, wheezing, and a racing heart. These symptoms result from excessive hormone levels and can significantly affect quality of life.

Importantly, liver-related symptoms don’t always reflect liver failure. The liver has large functional reserves, and it takes extensive damage to cause overt liver failure. That said, progressive liver compromise may lead to fluid retention, ascites, and confusion due to hepatic encephalopathy.

How Long Can You Live With Stage 4 Neuroendocrine Cancer in the Liver?

Life expectancy in this context is a deeply individual outcome influenced by tumor biology, response to treatment, and access to specialized care. While “stage 4” typically implies incurability, neuroendocrine tumors often behave differently from other cancers at the same stage.

Patients with well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors and liver metastases may live for many years—sometimes over a decade—especially if their disease is stable and responsive to systemic therapies. Median survival for these cases ranges from 70 to 130 months in some cohort studies. This stands in contrast to high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas, which carry a median survival closer to 12–18 months even with aggressive treatment.

Age, performance status, liver function, and comorbid conditions also play a role. A younger patient with isolated, treatable liver metastases will fare differently from someone with widespread disease and organ dysfunction. While statistics are helpful, prognosis must be personalized and discussed within the context of goals of care.

Hope is essential, but so is realism. Just as with seemingly unrelated illnesses where prognosis varies dramatically—such as functional bowel disorders explored in colorectal cancer vs IBS—understanding the biology behind a disease empowers better care.

Treatment Options for Liver Metastases in NETs

Therapy for liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors is usually multimodal, combining systemic treatments, localized liver-directed therapies, and sometimes surgery. Treatment choice depends on tumor grade, location, functional status, and symptom burden.

First-line systemic therapy for well-differentiated NETs includes somatostatin analogs like octreotide and lanreotide. These not only control hormonal symptoms but may slow tumor progression. In patients with progressive disease, options such as everolimus, sunitinib (for pancreatic NETs), or PRRT (peptide receptor radionuclide therapy) may be introduced.

Liver-directed treatments include embolization (TAE, TACE), radioembolization (Y90), or ablation. These therapies deliver local cytotoxic effects and can significantly reduce tumor load or control symptoms when systemic options are insufficient. In rare cases, surgical resection of liver lesions is possible, especially in oligometastatic disease or cytoreduction settings.

For high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, platinum-based chemotherapy is the standard, often with limited success. As disease progresses, best supportive care becomes central, emphasizing symptom relief and quality of life rather than disease control.

Comparison of Treatments and Their Impact on Prognosis

| Treatment Modality | Targeted Tumor Type | Goals of Therapy | Typical Outcome |

| Somatostatin analogs (SSA) | Well-differentiated NETs | Hormonal control, disease stabilization | Slows progression; 3–5 years median survival extension |

| PRRT (e.g., Lutetium-177) | SSTR-positive NETs | Tumor shrinkage, survival extension | Response in 30–40% of patients; durable disease control |

| Liver embolization (TACE, TARE) | Liver-dominant metastases | Reduce tumor burden and symptoms | Can extend survival and improve quality of life |

| Surgery (liver resection) | Limited liver metastases | Cytoreduction, potential cure | Rarely curative, but significant benefit in select patients |

| Systemic chemotherapy | High-grade NEC | Tumor shrinkage, symptom relief | Limited efficacy; median survival < 18 months |

Monitoring Disease Progression and Response to Treatment

Tracking the course of metastatic NETs in the liver requires ongoing imaging, laboratory monitoring, and clinical assessment. Contrast-enhanced MRI or CT scans are commonly used every 3 to 6 months to assess tumor growth or regression. Functional imaging, such as Ga-68 DOTATATE PET/CT, offers a high-sensitivity method for tracking somatostatin receptor expression and tumor spread.

Blood tests include markers like chromogranin A (CgA), pancreastatin, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE), depending on tumor type and grade. However, lab markers can be influenced by factors like kidney function or proton pump inhibitors, so results must be interpreted in context.

Clinical symptoms remain a vital part of monitoring. New or worsening abdominal pain, diarrhea, or fatigue may signal tumor progression or treatment side effects. It is also essential to track nutritional status, liver function, and psychological wellbeing, as these all affect long-term prognosis and decision-making.

Multidisciplinary teams—including oncologists, hepatologists, dietitians, and palliative care specialists—often coordinate this monitoring to ensure that treatment continues to align with patient goals and clinical reality.

Impact of Functional vs. Non-Functional Tumors on Prognosis

Neuroendocrine tumors are classified as functional or non-functional depending on whether they produce hormones that cause clinical symptoms. This distinction is crucial in evaluating both quality of life and survival outcomes in stage 4 disease with liver involvement.

Functional tumors often present earlier due to hormone-related syndromes. For example, carcinoid tumors may produce serotonin, leading to flushing, diarrhea, and heart valve damage. Gastrinomas and insulinomas can cause peptic ulcers or hypoglycemia. While early detection is an advantage, the presence of excessive hormones can lead to additional complications—such as carcinoid heart disease—which can negatively affect survival.

Non-functional tumors, by contrast, may remain undetected for longer periods, often presenting only when liver metastases are found incidentally or symptoms arise from tumor mass. While these tumors may lack hormonal symptoms, they can still behave aggressively depending on grade and differentiation.

Overall, prognosis tends to be better in functional tumors when caught early and managed effectively. However, symptom burden is often higher, and specialized care is required to control hormone-related complications.

Quality of Life Considerations in Advanced Disease

Stage 4 neuroendocrine cancer with liver metastases is a chronic and often complex condition. Patients live with both the physical burden of cancer and the psychosocial stress of an uncertain prognosis. Common quality-of-life issues include persistent fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, altered appetite, weight loss, and emotional distress.

Hormonal symptoms in functional NETs can be debilitating and unpredictable. Diarrhea, flushing, or wheezing may disrupt sleep and limit daily activities. In addition, repeated imaging, treatment cycles, and blood draws create a sense of ongoing medicalization of life, which can take a toll on mental health.

Supportive care becomes essential—not only at end-of-life stages but throughout the disease course. This includes nutritional support, symptom management (e.g., anti-diarrheals, anti-emetics), psychological counseling, and spiritual care if needed. Palliative interventions, such as ascites drainage or pain control, may also improve comfort without affecting tumor size.

Preserving dignity, independence, and social roles should be part of the care plan. Oncology is no longer about treating the tumor alone but treating the whole person, especially in long-term diseases like NETs.

Role of Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies

For patients with progressive disease despite standard therapy, clinical trials offer access to investigational treatments that may provide benefit. Trials may involve novel PRRT compounds, immunotherapy agents, or targeted therapies based on molecular profiling of tumor tissue.

While immunotherapy has shown modest success in poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas, its role in well-differentiated NETs is still under investigation. Some trials are exploring combinations of checkpoint inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, or drugs that target angiogenesis and tumor microenvironment.

Liquid biopsies, next-generation sequencing, and personalized medicine approaches are expanding in neuroendocrine oncology. These advances may help identify biomarkers that predict response or resistance to therapies.

Patients interested in clinical trials should discuss eligibility with their care team and consider referral to specialized cancer centers. Enrollment in a trial is not a guarantee of benefit, but for some, it offers hope when standard therapies have been exhausted.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors in Long-Term Management

Although NETs are not strongly linked to lifestyle-related carcinogens, maintaining good overall health can influence treatment tolerance and emotional resilience. Proper nutrition, hydration, moderate physical activity, and stress management improve recovery after interventions and maintain muscle mass and energy levels.

Alcohol and hepatotoxic substances should be avoided, particularly in those with significant liver involvement. Certain foods may aggravate hormonal symptoms—such as foods high in serotonin or tyramine—so dietary counseling can be helpful, especially for functional tumors.

Emotional support and stress reduction also play a critical role. While NETs are not classified as psychosomatic diseases, emotional well-being affects immune function, sleep, digestion, and hormone balance. Structured psychosocial care has been shown to improve outcomes across many cancer types.

This holistic approach mirrors discussions seen in does polyester cause cancer, where the importance of chronic, low-level environmental exposure and stress on long-term health is explored in a non-obvious but meaningful way.

Surgical Options and Liver Resection in Select Cases

While surgery is rarely curative in stage 4 neuroendocrine cancer, it can still play an important role. Liver resection is considered in patients with limited hepatic metastases—particularly when the primary tumor is controlled and liver function is preserved. This is known as cytoreductive or debulking surgery.

The goal is not necessarily to eliminate all disease, but to remove the bulk of tumor burden, reducing hormonal output and allowing systemic therapies to work more effectively. Studies show that patients undergoing liver resection may experience improved survival and better symptom control, especially when more than 70% of tumor mass can be removed.

Surgical candidacy depends on tumor distribution, patient health, and liver reserve. Modern techniques, including laparoscopic and robotic-assisted approaches, reduce recovery time and complication rates. However, surgery must be considered in the context of disease biology—particularly tumor grade and growth rate.

For high-grade or widespread liver metastases, surgery is generally not indicated. In such cases, non-surgical local therapies or systemic treatment provide a better balance of risk and benefit.

End-of-Life Considerations and Hospice Care

For patients with progressive stage 4 disease despite all available therapies, the focus often shifts from treatment to comfort. Palliative care—when initiated early—can provide significant relief from physical symptoms and emotional burden. Contrary to common misconception, palliative care is not only for the dying but also for the living.

Hospice care becomes appropriate when life expectancy is estimated at six months or less and when the primary goal is quality of life rather than disease control. This can be provided at home, in dedicated facilities, or within hospitals. Key components include pain management, symptom relief (e.g., controlling ascites or nausea), spiritual support, and assistance for families.

Deciding to transition to hospice is not a failure. It is an acknowledgment of human limits and a shift toward comfort, dignity, and closure. Open discussions about prognosis, values, and legacy can guide these decisions in a way that respects each patient’s wishes.

The earlier these conversations begin, the more meaningful they become—offering space for planning, healing, and peace.

Communicating Prognosis with Patients and Families

Discussing prognosis is one of the most delicate tasks in oncology. In stage 4 neuroendocrine cancer with liver metastases, honesty must be balanced with compassion and tailored to each individual’s needs and values. Some patients want detailed statistics; others prefer broad overviews or emotional reassurance.

Clear communication requires preparation. Clinicians should understand the latest data, be transparent about uncertainty, and avoid overly optimistic or pessimistic tones. Using phrases like “most people in your situation…” helps set realistic expectations while preserving hope.

Involving family members in these conversations—when permitted by the patient—can foster shared understanding and reduce later confusion or distress. Providing printed materials, prognosis charts, or referrals to patient navigators and counselors can aid comprehension.

The goal isn’t to predict the future exactly, but to help the patient prepare emotionally and practically for what lies ahead. Language matters. Tone matters. And respect matters above all.

Living with Stage 4 NETs and Liver Metastases

Living with stage 4 neuroendocrine cancer that has spread to the liver is undeniably complex—but not hopeless. Prognosis depends on tumor grade, disease burden, and response to therapy. Many patients live for years, especially with well-differentiated tumors and access to modern, multidisciplinary care.

Treatment can include systemic therapy, liver-directed procedures, and sometimes surgery, supported by comprehensive monitoring and symptom control. Quality of life, patient values, and emotional resilience are just as important as any clinical variable.

Hope in oncology isn’t the same as false reassurance. It’s about making each day count, maximizing comfort and clarity, and staying informed. With the right support, even in advanced disease, life can still be meaningful, connected, and dignified.

FAQ: Stage 4 Neuroendocrine Cancer Spread to Liver — Life Expectancy and Care

What does stage 4 neuroendocrine cancer mean?

It means the cancer has metastasized—spread beyond the primary site—to distant organs, most commonly the liver, lungs, or bones. At this stage, the disease is incurable but often manageable for long periods.

How long can you live with liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors?

Survival varies widely. Some patients live more than 10 years with treatment, while others with aggressive tumors may live only 12 to 24 months. The key factors are tumor grade, treatment response, and overall health.Does liver involvement always mean a poor prognosis?

Does liver involvement always mean a poor prognosis?

Not necessarily. Patients with limited, well-differentiated liver metastases often have better outcomes, especially if treatment is initiated early and disease is slow-growing.

Is surgery an option in stage 4 NET with liver spread?

Yes, in selected cases where liver lesions are few and resectable. Surgery is more common in low-grade tumors and when at least 70% of tumor volume can be removed.

What are signs that liver metastases are progressing?

New abdominal pain, increasing fatigue, weight loss, or jaundice may indicate disease progression. Lab abnormalities or changes on imaging also help assess this.

Can neuroendocrine liver metastases be treated directly?

Yes. Local treatments like embolization, ablation, or radioembolization can target liver tumors specifically and control symptoms or tumor growth.

Are hormone symptoms worse with liver metastases?

Yes, especially in functional NETs. The liver normally filters hormones; when it’s compromised, hormone-related symptoms like flushing or diarrhea may worsen.

What is the difference between functional and non-functional NETs?

Functional tumors produce hormones that cause symptoms; non-functional tumors do not. Prognosis and management differ depending on tumor type and behavior.

What treatments improve survival in metastatic NETs?

Somatostatin analogs, PRRT, liver-directed therapies, and (in select cases) surgery are commonly used. Chemotherapy is mainly for high-grade tumors.

Is PRRT available for all patients with NETs?

No. PRRT is generally used for patients whose tumors express somatostatin receptors. Eligibility is determined through imaging and specialist evaluation.

What are common emotional struggles with this diagnosis?

Anxiety, uncertainty, and fear of progression are common. Support groups, counseling, and open communication with providers can help ease emotional distress.

Can hospice help even if I’m not in pain?

Yes. Hospice provides holistic care for patients nearing end of life, including emotional, social, and spiritual support—not just pain management.

Does having NET mean I have to give up work or social life?

Not necessarily. Many people continue working and maintaining social lives during treatment, especially with stable disease and symptom control.

Are clinical trials worth considering?

Yes, especially if standard therapies are exhausted. Trials offer access to cutting-edge treatments, but risks and expectations should be carefully discussed.

Should I get a second opinion?

Absolutely. NETs are complex, and second opinions from specialized cancer centers can clarify options and ensure you’re receiving optimal care.