Understanding Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs: Diagnosis, Stages, and Treatment from a Veterinary Perspective

- Introduction: What Is Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs?

- Causes and Risk Factors of Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs

- Recognizing the Symptoms of Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs

- Diagnostic Process and Imaging Techniques

- Tumor Classification and Staging

- Treatment Options for Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs

- Prognosis and Life Expectancy After Diagnosis

- Managing Quality of Life During and After Treatment

- Preventive Measures and Early Detection Strategies

- Breed Susceptibility and Genetic Considerations

- Differences Between Benign and Malignant Salivary Tumors

- Postoperative Recovery and Owner Responsibilities

- Emotional Support for Pet Owners Facing Canine Cancer

- Metastasis and Systemic Spread of Salivary Gland Cancer

- Comparative Oncology: How Salivary Cancer in Dogs Resembles Human Cases

- When Euthanasia Becomes a Compassionate Choice

- Long-Term Monitoring and Recurrence Prevention

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Introduction: What Is Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs?

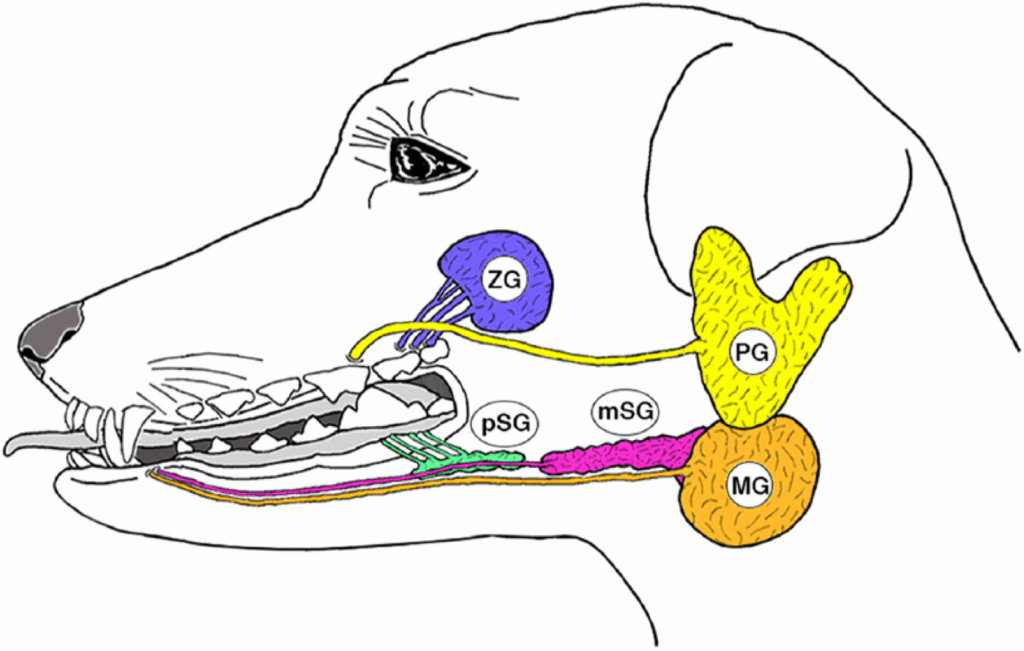

Salivary gland cancer in dogs is a rare but serious condition that involves the malignant transformation of cells within the salivary glands. Dogs have multiple salivary glands located near the jaw, tongue, and throat. When one of these glands develops a tumor, it can interfere with basic functions such as eating, breathing, and swallowing. Although this cancer is uncommon, early recognition and intervention significantly improve outcomes. As a veterinarian, I’ve seen that awareness and swift decision-making from dog owners make a substantial difference in prognosis and quality of life.

These tumors are often categorized as adenocarcinomas, which means they arise from the glandular tissue responsible for producing saliva. Other types, such as squamous cell carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinomas, can also be present but are less frequent. While these cancers can be aggressive, some respond well to surgery and radiation therapy if detected early.

Causes and Risk Factors of Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs

Genetic and Environmental Influences

The exact cause of salivary gland cancer in dogs remains unknown, but several contributing factors are suspected. Genetic predisposition plays a role, especially in certain breeds like Spaniels and Retrievers. These breeds are reported more frequently with head and neck tumors, though direct studies on salivary cancers remain limited.

Environmental exposures also warrant consideration. Dogs that live in urban areas with higher pollution levels or those exposed to second-hand smoke may have an elevated risk. Chronic inflammation or trauma to the mouth and jaw region has also been suggested as a possible precursor to tumor development, although clinical proof is sparse.

Hormonal and Age-Related Factors

Hormonal imbalances and advanced age are common risk factors. Most salivary gland tumors are diagnosed in older dogs, typically over the age of 8. The aging process makes cells more susceptible to mutations that could initiate tumor formation. While there is no strong evidence that neutering or spaying affects risk in this specific cancer type, hormonal dynamics in general contribute to tumor growth in various tissues.

Interestingly, parallels have been drawn with human oncology, where glandular cancers sometimes arise due to hormonal dysfunction or prolonged hormonal therapy.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs

External Signs Near the Jaw and Neck

The most common visible sign is swelling near the jawline, under the tongue, or around the neck. Owners often first notice a lump near the cheek or throat, which may or may not be painful. In early stages, these lumps might be mistaken for benign cysts or lymph node enlargements.

The swelling may gradually enlarge, leading to facial asymmetry or skin ulceration in advanced cases. Because these tumors grow in confined anatomical spaces, they can quickly interfere with other structures, causing changes in facial movement or eye function if the tumor invades nearby nerves.

Systemic Symptoms and Behavior Changes

Internally, dogs may experience difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), excessive drooling, or even bloody saliva. As the cancer progresses, you may notice reduced appetite, weight loss, and increased lethargy. Dogs can also become more irritable or withdrawn due to discomfort in the head and neck area.

Some dogs develop secondary infections in the mouth due to open tumor surfaces, which produce foul-smelling breath and pus discharge. In advanced stages, breathing issues may arise if the tumor obstructs the airway or infiltrates the nasal passages.

Diagnostic Process and Imaging Techniques

Physical Examination and Palpation

Veterinarians begin with a thorough physical exam, focusing on the oral cavity and cervical region. The vet will palpate for asymmetry, firmness, and mobility of the swelling. Tumors in the salivary glands typically feel firm and may be fixed in place, unlike softer fluid-filled cysts.

During the initial visit, your vet may check lymph nodes and perform an oral examination under mild sedation if the mass is deep or the dog is in pain. Observations such as tissue ulceration or asymmetrical gland size are important indicators that prompt further investigation.

Biopsy and Imaging Modalities

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is commonly used for a preliminary diagnosis. A small needle extracts cells from the lump for cytological evaluation. If the results are inconclusive or if deeper tissue evaluation is required, a core biopsy or incisional biopsy under general anesthesia may be needed.

Imaging is essential for both diagnosis and staging. CT scans are preferred for evaluating the tumor’s size and its relationship to surrounding structures. MRI can be helpful when nerve involvement is suspected, especially if the dog has facial drooping or muscle atrophy. Chest X-rays and abdominal ultrasound are used to assess potential metastasis. Transverse colon cancer the same applies to oncological diagnostics and the importance of identifying metastases.

Tumor Classification and Staging

| Tumor Type | Description | Common Features | Prognosis |

| Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma | Mixed tumor of mucus and squamous cells | Irregular swelling, may ulcerate | Moderate |

| Adenocarcinoma | Arises from glandular tissue | Firm, invasive mass near jaw | Variable |

| Acinic Cell Carcinoma | Relatively well-differentiated tumor | Often less aggressive | Favorable |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Involves epithelial lining of ducts | Aggressive, rapid growth | Poor |

| Undifferentiated | Poorly defined cellular origin | Very aggressive, high metastasis risk | Poor |

Staging considers tumor size, lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis (TNM system). Early-stage tumors are localized and easier to treat surgically. Advanced-stage cancers with lymph node or lung involvement are managed more conservatively, often with palliative care.

Treatment Options for Salivary Gland Cancer in Dogs

Surgery as the Primary Approach

Surgical excision remains the cornerstone of treatment for salivary gland cancer in dogs. Complete removal of the tumor, including affected tissue and sometimes adjacent lymph nodes, offers the best chance for long-term control. Depending on the location of the tumor—such as near the parotid, mandibular, or sublingual glands—the surgical approach may vary significantly in complexity and invasiveness.

In most cases, achieving clean margins is the goal, meaning that no cancer cells are present at the edges of the excised tissue. When complete removal isn’t possible due to involvement of nerves or major vessels, debulking may still provide temporary relief from symptoms like pressure and obstruction. Postoperative care includes managing pain, swelling, and infection risk, with many dogs recovering well if complications are minimized.

Adjunctive Therapies: Radiation and Chemotherapy

Radiation therapy is frequently recommended when surgical margins are incomplete or if the tumor shows signs of local invasiveness. It can also be used as a primary therapy in cases where surgery isn’t feasible due to location or health constraints. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) allows precise targeting, reducing damage to surrounding tissues like the brain or trachea.

Chemotherapy is less effective for this cancer type but may be considered in metastatic cases or for specific tumor histologies, such as undifferentiated carcinomas. Protocols involving carboplatin or doxorubicin are typically used, but response rates vary. Treatment planning is always customized, balancing efficacy, side effects, and the dog’s quality of life.

Prognosis and Life Expectancy After Diagnosis

Influencing Factors on Prognosis

Several factors determine how well a dog responds to treatment. Tumor type and grade are central: low-grade tumors such as acinic cell carcinoma tend to grow slowly and respond better to surgery, while high-grade tumors like squamous cell carcinoma are more aggressive and prone to recurrence.

Tumor size at diagnosis is another major factor. Smaller, localized tumors that haven’t invaded lymph nodes or metastasized generally have a favorable prognosis. Complete surgical removal, with no residual cells, further improves outcomes. Conversely, if the cancer has spread to the lungs or brain, the prognosis is poor regardless of therapy.

Average Survival Times and Recurrence Rates

With early surgical intervention, many dogs live 1 to 3 years post-treatment, especially if supported with radiation therapy. Some even survive longer, depending on tumor biology and individual resilience. However, recurrence is a valid concern. Local recurrence can occur within months if surgical margins were not clean or if microscopic disease remained undetected.

Routine follow-ups every 3 to 6 months help monitor for recurrence through imaging and physical exams. Even if recurrence occurs, secondary interventions like radiation can help extend the dog’s life and maintain comfort.

Managing Quality of Life During and After Treatment

Supportive Care for Pain, Appetite, and Stress

Beyond clinical treatment, managing quality of life is a vital part of veterinary oncology. Dogs undergoing surgery or radiation often experience discomfort, fatigue, and emotional changes. Effective pain management using NSAIDs, gabapentin, or opioids helps maintain activity and sleep patterns. For dogs experiencing nausea from chemotherapy, medications like maropitant or ondansetron can be prescribed.

Appetite stimulants such as mirtazapine or capromorelin may be introduced if weight loss becomes severe. Ensuring easy-to-eat meals—softened or blended—is often necessary after surgery or when oral tumors restrict chewing. Creating a calm, predictable routine with plenty of affection and rest is just as critical as any clinical protocol.

Monitoring Long-Term Complications

Even after recovery, dogs need ongoing observation for side effects. Scar tissue can occasionally impact nerve function, causing facial drooping or reduced mobility in the jaw. Radiation therapy may cause tissue fibrosis or dryness in the mouth, which can lead to gum infections and dental decay.

Owners should work with their veterinarians on a long-term care plan that includes oral hygiene checks, periodic bloodwork, and behavior assessments. Early detection of any setbacks—be it recurrence or therapy-related complications—greatly improves the chances of timely management. When speaking about the possibility of long-term inflammation as a factor for mutations, one cannot help but recall does tattoo removal cause cancer.

Preventive Measures and Early Detection Strategies

Importance of Regular Vet Visits and Home Monitoring

Although salivary gland cancer cannot always be prevented, early detection is achievable through consistent veterinary care. Routine wellness exams should include careful palpation of the head and neck, especially for breeds with known predispositions. When lumps are detected early—before they become painful or ulcerated—treatment outcomes are significantly improved.

At home, dog owners should get in the habit of gently checking the jawline and throat area during grooming sessions. Noticing asymmetry, persistent drooling, or unusual odors should prompt a vet visit. Behavioral changes like head shaking, pawing at the mouth, or disinterest in food are early warning signs worth investigating.

Reducing Environmental and Lifestyle Risks

While research is still limited, reducing exposure to carcinogens may help lower the risk of developing salivary tumors. Avoiding environments with heavy smoke, using stainless steel or ceramic food bowls instead of plastic, and maintaining good oral hygiene can reduce chronic irritation of oral tissues.

For pet owners in urban or industrialized areas, keeping dogs indoors during high pollution periods and using air purifiers at home may offer additional protection. A healthy diet rich in antioxidants may also support general cellular resilience, although no specific diet is proven to prevent this cancer.

Breed Susceptibility and Genetic Considerations

Breeds with Higher Incidence

Although salivary gland cancer is rare, some dog breeds appear more predisposed than others. Among the most frequently noted are Cocker Spaniels, Golden Retrievers, and Poodles. These breeds have a higher incidence of oral and head/neck tumors in general, which may reflect underlying genetic vulnerabilities or structural predispositions in glandular tissue.

For example, Retrievers are also at higher risk for other glandular tumors, such as thyroid and anal sac adenocarcinomas, suggesting that glandular tissues in these dogs may be more prone to malignancy. While no breed-specific gene mutation has yet been linked directly to salivary gland cancer, the pattern of increased diagnosis in certain breeds raises suspicion of a hereditary component.

Role of Hereditary and Epigenetic Factors

In veterinary oncology, research on hereditary cancer risk is still emerging. Mutations in tumor suppressor genes or in DNA repair pathways may increase a dog’s likelihood of developing cancers, including in salivary tissues. Epigenetic influences—changes in gene expression due to environment or age—may also contribute, especially in breeds where high cancer rates are observed despite varied environments.

Breeders and owners of high-risk breeds should prioritize regular head and neck exams, especially in dogs over age 7. Additionally, when selecting breeding pairs, avoiding lines with recurrent cancer diagnoses may help reduce risk in future generations.

Differences Between Benign and Malignant Salivary Tumors

Diagnostic Challenges in Early Stages

One of the key difficulties in managing salivary gland tumors in dogs is distinguishing benign from malignant forms early on. Both may appear as firm swellings and neither is painful in the beginning. However, benign tumors such as adenomas tend to grow very slowly and remain well-circumscribed, while malignant tumors like adenocarcinomas are more infiltrative and often distort surrounding tissues.

In some cases, an initial fine needle aspiration might only reveal non-specific inflammation or mixed cellular populations, leading to diagnostic delays. Only a surgical biopsy with histopathological grading can provide a definitive distinction between benign and malignant tumors.

Long-Term Behavior and Prognosis

Benign tumors usually pose minimal risk unless they obstruct critical anatomical structures or become secondarily infected. Surgical removal is typically curative. Malignant tumors, by contrast, often recur and metastasize to regional lymph nodes or lungs. Their cellular structure tends to show rapid division, poor differentiation, and vascular invasion—all hallmarks of aggressive disease.

Understanding the difference between the two is critical not only for treatment planning but also for setting expectations with pet owners. A benign tumor may need only minor surgical attention, while malignancies call for a long-term care strategy.

Postoperative Recovery and Owner Responsibilities

Wound Management and Medication

After surgery to remove a salivary gland tumor, your dog will typically have a visible incision on the neck or side of the face, which requires careful monitoring. Vets often use absorbable sutures beneath the skin, but the outer layers may still need cleaning and protection from licking or scratching. A protective cone (Elizabethan collar) is almost always recommended during recovery.

Dogs will be prescribed antibiotics to prevent infection and pain medication to ensure comfort. Swelling is expected in the first few days, but should steadily decrease. Any signs of pus, increasing redness, or foul odor around the incision must be reported immediately. Feeding soft foods and maintaining hydration help support tissue healing.

Emotional Recovery and Routine Re-establishment

Beyond physical healing, dogs also need time to emotionally adjust. Some may experience temporary anxiety, lethargy, or clinginess following surgery, especially if their routines were disrupted. Gentle reassurance, a quiet space to rest, and familiar smells can ease this transition. Most dogs begin returning to their usual habits within 7–10 days, although full energy levels may take a few weeks to return.

Regular follow-up visits are essential to remove any external sutures, assess healing, and monitor for early signs of recurrence. Your vet will typically schedule checkups at 1 week, 1 month, and then every 3 to 6 months thereafter.

Emotional Support for Pet Owners Facing Canine Cancer

Navigating the Initial Shock

Receiving a cancer diagnosis for your dog can feel overwhelming and devastating. Many pet owners describe intense grief, confusion, or helplessness in the early days after diagnosis. It’s important to acknowledge these feelings and seek support—from veterinarians, family, or online communities of dog owners who’ve gone through similar experiences.

Veterinarians play a key role in helping owners feel empowered. A good veterinary oncology team will take the time to explain the diagnosis, treatment options, costs, and expected outcomes in detail, providing a roadmap for what comes next. Clarity and empathy are essential at this stage, both for emotional well-being and practical decision-making.

Making Informed and Compassionate Decisions

Some owners struggle with the question of whether aggressive treatment is worth it, especially if the dog is elderly or already in decline. Quality of life—not just quantity—should be at the heart of all decisions. Choosing palliative care is not giving up; it’s prioritizing comfort and dignity. On the other hand, many dogs tolerate treatment surprisingly well and bounce back with energy, especially when pain is effectively managed.

Making these decisions is easier when you’re informed, supported, and guided by professionals who care deeply about your pet’s welfare. Remember that your bond with your dog is unique, and whatever path you choose, your compassion is central to their comfort.

Metastasis and Systemic Spread of Salivary Gland Cancer

Common Sites of Metastasis

When salivary gland cancer spreads beyond its original site, it often follows predictable patterns. The most common destinations are regional lymph nodes—especially mandibular and retropharyngeal nodes—followed by the lungs. In rare cases, metastases may reach the bones or liver, particularly in aggressive tumor types such as undifferentiated carcinomas or squamous cell carcinoma.

Once lymphatic spread is confirmed, prognosis typically worsens. A CT scan or ultrasound may be used to assess lymph node enlargement, and fine needle aspirates can provide cytologic confirmation. If pulmonary spread is suspected, chest radiographs or thoracic CT imaging are the diagnostic tools of choice.

Impact on Treatment Options and Survival

The presence of metastasis changes the therapeutic strategy. While surgery might still be considered for symptom relief, the likelihood of achieving a cure diminishes. In these cases, the focus often shifts toward slowing tumor progression and maintaining comfort. Radiation and chemotherapy may be used palliatively, aiming not to eradicate cancer, but to control its effects.

Owners should be prepared for a more aggressive monitoring schedule in metastatic cases, with regular imaging every 2–3 months. Still, some dogs with stable lung metastases can live comfortably for extended periods with the right care and symptom control.

Comparative Oncology: How Salivary Cancer in Dogs Resembles Human Cases

Shared Biology and Diagnostic Methods

Salivary gland cancer in dogs shares many features with its human counterpart. Both species experience tumors in similar anatomical locations, such as the parotid and submandibular glands, and the histologic classifications—adenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid, and acinic cell—are consistent across both.

This similarity allows veterinarians to adopt diagnostic and therapeutic approaches from human oncology. Techniques like CT-guided biopsies, radiation planning using IMRT, and systemic chemotherapy protocols mirror those used in people. Comparative oncology is a growing field, advancing both veterinary and human treatments through cross-species studies.

Implications for Research and Future Therapies

The overlap in disease mechanisms means that canine salivary tumors are sometimes used as models for human research. Clinical trials in veterinary medicine may test new therapies or surgical methods before they’re considered for human use. In return, veterinary oncologists gain access to cutting-edge treatments developed for people.

This collaboration holds promise for the future. New molecular treatments, such as targeted therapies or immunomodulators, may one day improve outcomes for dogs with salivary gland cancer, especially those with aggressive or inoperable tumors.

When Euthanasia Becomes a Compassionate Choice

Recognizing End-Stage Signs

There comes a point when cancer treatment may no longer provide meaningful relief. Advanced salivary gland cancer can cause severe pain, obstruct breathing or eating, and lead to profound fatigue or weight loss. If a dog no longer enjoys food, play, or affection—core pleasures that define quality of life—it may be time to consider humane euthanasia.

Veterinarians can help you assess these signs objectively through quality-of-life scoring systems. These include evaluating appetite, hydration, mobility, comfort, and mood. Decline in multiple areas over time usually signals that the disease has entered a terminal phase.

The Euthanasia Process and Emotional Closure

Euthanasia is a deeply personal decision, yet it is also a final act of compassion when suffering outweighs moments of peace. The process is gentle and usually involves two injections: the first for sedation, and the second for a painless passing. Most clinics allow the family to be present, hold the pet, and say goodbye in a calm setting.

Grief is natural and valid. Take time to process, talk, or even create a memorial to honor your dog’s life. Many owners find comfort in knowing they gave their companion a peaceful end, free from fear or prolonged pain.

Long-Term Monitoring and Recurrence Prevention

Follow-Up Schedules and Screening

For dogs who undergo successful treatment, vigilant follow-up care is crucial. The highest risk of recurrence typically lies within the first 12 months after surgery or radiation. Veterinarians will recommend rechecks every 3 months initially, then every 6 months, depending on tumor behavior and the dog’s response.

Routine physical exams, regional lymph node palpation, and imaging are part of this long-term strategy. Bloodwork can also help detect signs of systemic impact, especially in dogs who received chemotherapy.

Lifestyle and Health Maintenance

There’s no guaranteed way to prevent recurrence, but maintaining excellent overall health helps your dog’s immune system perform optimally. A balanced diet, routine dental care, and stress-free home life contribute to better recovery and resilience.

Some owners choose holistic adjuncts—such as acupuncture, medicinal mushrooms, or CBD oil—with the support of their veterinary team. While not a replacement for medical therapy, these may offer comfort and emotional support during recovery and beyond.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is salivary gland cancer in dogs?

It is a malignant growth that originates in one of the dog’s salivary glands, often affecting the mandibular, parotid, or sublingual glands. The tumor disrupts saliva production and can infiltrate surrounding tissues, leading to swelling, pain, and functional problems.

How rare is this type of cancer in dogs?

Salivary gland tumors are considered uncommon, representing less than 1% of all canine cancers. Because of their rarity, they are sometimes misdiagnosed or identified late in the disease process.

What breeds are more likely to develop salivary gland cancer?

Certain breeds, such as Cocker Spaniels, Golden Retrievers, and Standard Poodles, appear to have a higher incidence. However, any breed can be affected, especially older dogs.

Is salivary gland cancer painful for dogs?

It can become very painful in advanced stages. Initially, dogs may not show discomfort, but as the tumor enlarges, it can press on nerves, obstruct swallowing, or ulcerate, leading to significant pain.

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves physical examination, imaging (such as CT or MRI), and biopsy. Fine needle aspiration may be used initially, but surgical biopsy is the gold standard for confirming malignancy.

Can the cancer spread to other parts of the body?

Yes. It often spreads to nearby lymph nodes and, in more aggressive cases, to the lungs, liver, or bones. Staging tests are critical to determine the extent of the disease.

What is the main treatment?

Surgical removal is the primary treatment. If the tumor cannot be completely removed or is highly invasive, radiation therapy and, in some cases, chemotherapy may be used.

How successful is treatment?

Success depends on factors like tumor type, size, and stage. Dogs with small, localized tumors often have good outcomes, especially with complete surgical excision and clean margins.

Will my dog need chemotherapy?

Not always. Chemotherapy is usually reserved for cases with metastasis or particularly aggressive tumor types. It’s less commonly used than surgery or radiation.

How long can a dog live after diagnosis?

Survival varies. Dogs with early-stage, surgically removed tumors can live several years. Those with advanced or metastatic disease may live only months, depending on response to treatment.

Can salivary gland cancer come back?

Yes. Even with surgery, recurrence is possible, particularly if the tumor was incompletely excised. Routine follow-ups are necessary to catch recurrence early.

Should I consider palliative care instead of aggressive treatment?

Palliative care is a valid option, especially for older dogs or those with advanced disease. It focuses on comfort and quality of life rather than curing the cancer.

Is euthanasia ever the best choice?

In terminal stages with unmanageable pain or functional impairment, euthanasia can be the most compassionate choice to prevent prolonged suffering.

Can I do anything to prevent this cancer?

There’s no guaranteed prevention, but reducing environmental toxins, avoiding second-hand smoke, and maintaining regular vet visits may help with early detection and risk reduction.

Does this condition resemble any other cancers?

Yes. It shares biological and clinical similarities with some human glandular cancers and is often studied alongside other head-and-neck cancers like transverse colon or prostate conditions.