Understanding Lung Cancer Metastasis to the Breast: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prognosis

- What Is Lung Cancer Metastasis to the Breast?

- Epidemiology and Rarity of Breast Metastasis from Lung Origin

- Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Metastatic Spread

- Clinical Presentation and Early Warning Signs

- Diagnostic Challenges in Differentiating Primary Breast Cancer from Lung Metastases

- Role of Imaging in Detecting Breast Metastasis from Lung Cancer

- Histopathological Findings and Biomarkers in Confirmation

- Treatment Approaches: Systemic and Localized Options

- Prognosis and Survival Rates in Patients with Breast Metastases from Lung Cancer

- Hormone Receptors and HER2 Expression in Breast Metastasis from Lung Cancer

- Patient-Centered Care and Palliative Considerations

- Key Differences Between Primary Breast Cancer and Lung Cancer Metastasis

- Impact of Lung Cancer Subtype on Breast Metastatic Behavior

- Role of Biopsy and Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis

- Treatment Outcomes and Emerging Research

- Psychosocial Support for Patients with Rare Metastases

- FAQ

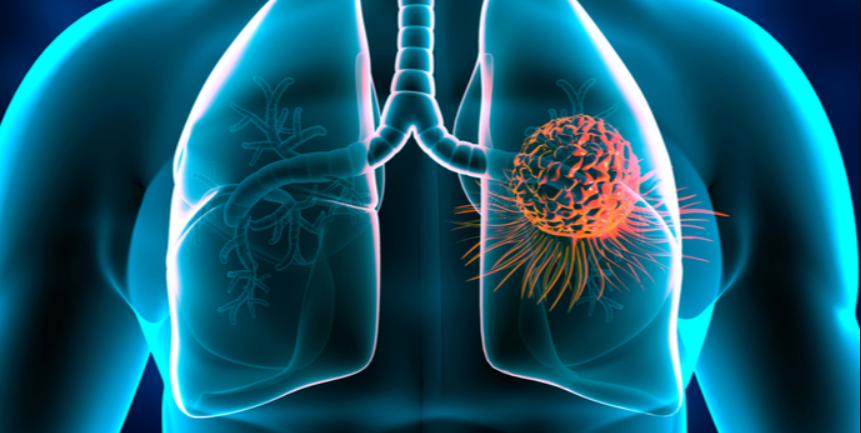

What Is Lung Cancer Metastasis to the Breast?

Lung cancer metastasis to the breast refers to the spread of primary lung cancer cells to breast tissue. Although lung cancer commonly metastasizes to the brain, bones, liver, and adrenal glands, breast involvement is highly unusual and accounts for a very small fraction of secondary breast malignancies. This phenomenon occurs when cancer cells break away from the primary tumor in the lung, travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, and settle in the breast, where they begin to grow. It is critical to distinguish metastatic lung cancer from primary breast cancer, as treatment strategies and prognostic implications differ significantly. Advanced imaging and histopathological analysis are required to make this distinction clear.

Epidemiology and Rarity of Breast Metastasis from Lung Origin

Secondary breast tumors from lung primaries are rare, comprising less than 1% of all breast malignancies. This low frequency is likely due to the unique microenvironment of breast tissue, which is not typically conducive to colonization by lung cancer cells. Most reported cases involve non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), particularly adenocarcinoma, although small cell lung carcinoma has also been documented. Women are more frequently diagnosed with this type of metastasis, not necessarily due to higher biological susceptibility, but because breast tissue is more commonly monitored and investigated in female patients. Nonetheless, both sexes may be affected. The infrequency of this condition can lead to delayed diagnosis and misclassification as primary breast cancer, further underscoring the need for thorough diagnostic evaluation.

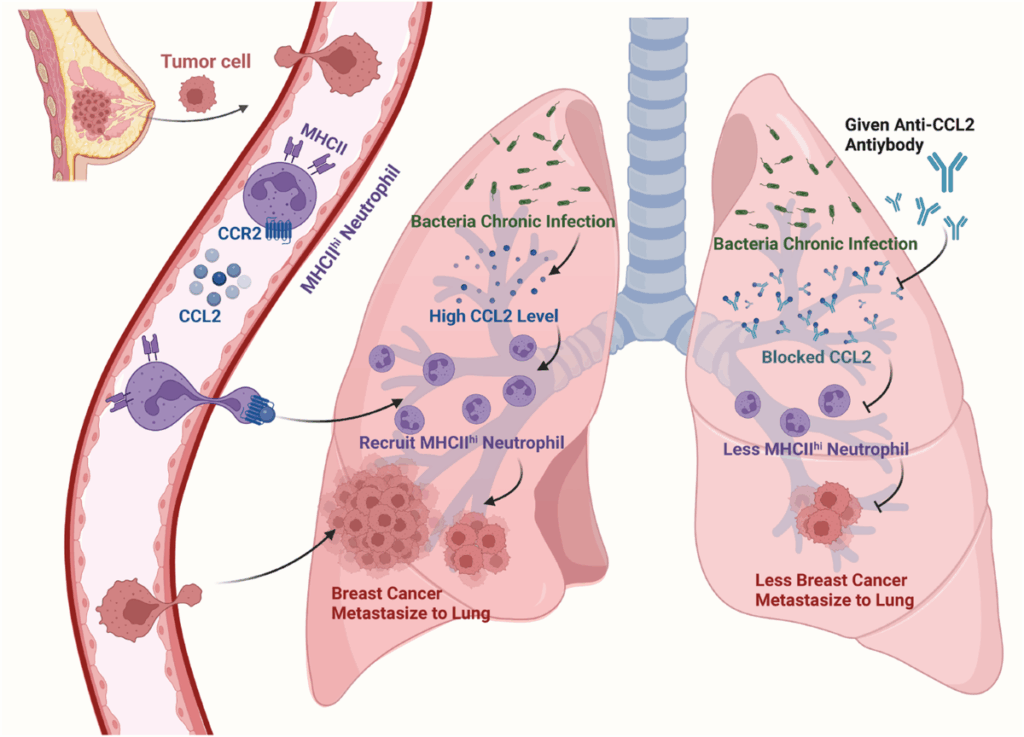

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Metastatic Spread

The process by which lung cancer spreads to the breast involves several biological mechanisms. Hematogenous dissemination is the most probable route, as lung cancer cells may enter the systemic circulation and bypass the lungs’ filtering mechanism, ultimately reaching the vascular-rich breast tissue. Alternatively, retrograde lymphatic spread may occur if lymphatic channels are disrupted, often by tumor burden or prior interventions. Once within the breast, cancer cells must adapt to the local environment, evade immune detection, and stimulate angiogenesis to thrive. These requirements may explain why such metastases are uncommon. Additionally, molecular factors such as the expression of certain adhesion molecules and mutations may influence a tumor’s metastatic behavior, which is actively studied in parallel research on lewis lung cancer and t cell exhaustion.

Clinical Presentation and Early Warning Signs

Patients with lung cancer metastasis to the breast often present with symptoms that mimic primary breast cancer. These may include a palpable lump, localized pain, skin retraction, or changes in nipple appearance. However, some unique characteristics can raise clinical suspicion. For example, metastatic lesions tend to be superficial, well-circumscribed, and lack microcalcifications commonly seen in primary breast tumors. Additionally, they may be associated with systemic symptoms such as weight loss, cough, or dyspnea, which reflect the underlying lung disease. In rare cases, the breast lesion may be the first noticeable manifestation, preceding the diagnosis of lung cancer itself. This highlights the importance of considering a metastatic origin when evaluating new breast masses, particularly in patients with a known history or risk factors for lung cancer, including heavy smoking or prior thoracic malignancy. In such cases, PET imaging can aid diagnosis — as discussed in our related resource.

Diagnostic Challenges in Differentiating Primary Breast Cancer from Lung Metastases

Distinguishing between a primary breast tumor and metastasis from lung cancer poses a significant diagnostic challenge, particularly when there is no prior history of lung malignancy. While imaging tools such as mammography and ultrasound provide preliminary insight, they cannot definitively determine tumor origin. A breast lesion that appears well-circumscribed without spiculated margins or calcifications may raise suspicion of a metastatic tumor, especially if accompanied by systemic signs. However, definitive diagnosis requires a tissue biopsy and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis. Pathologists look for specific markers like TTF-1 (thyroid transcription factor-1), which is typically positive in lung adenocarcinomas and negative in breast carcinoma. Other relevant markers include Napsin A, cytokeratin 7, and ER/PR/HER2 receptors. Combining clinical data, radiologic features, and histological findings is the cornerstone of accurate classification.

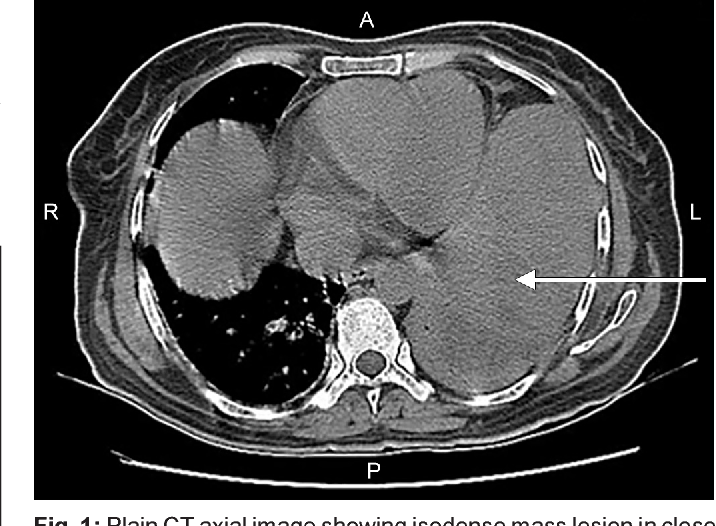

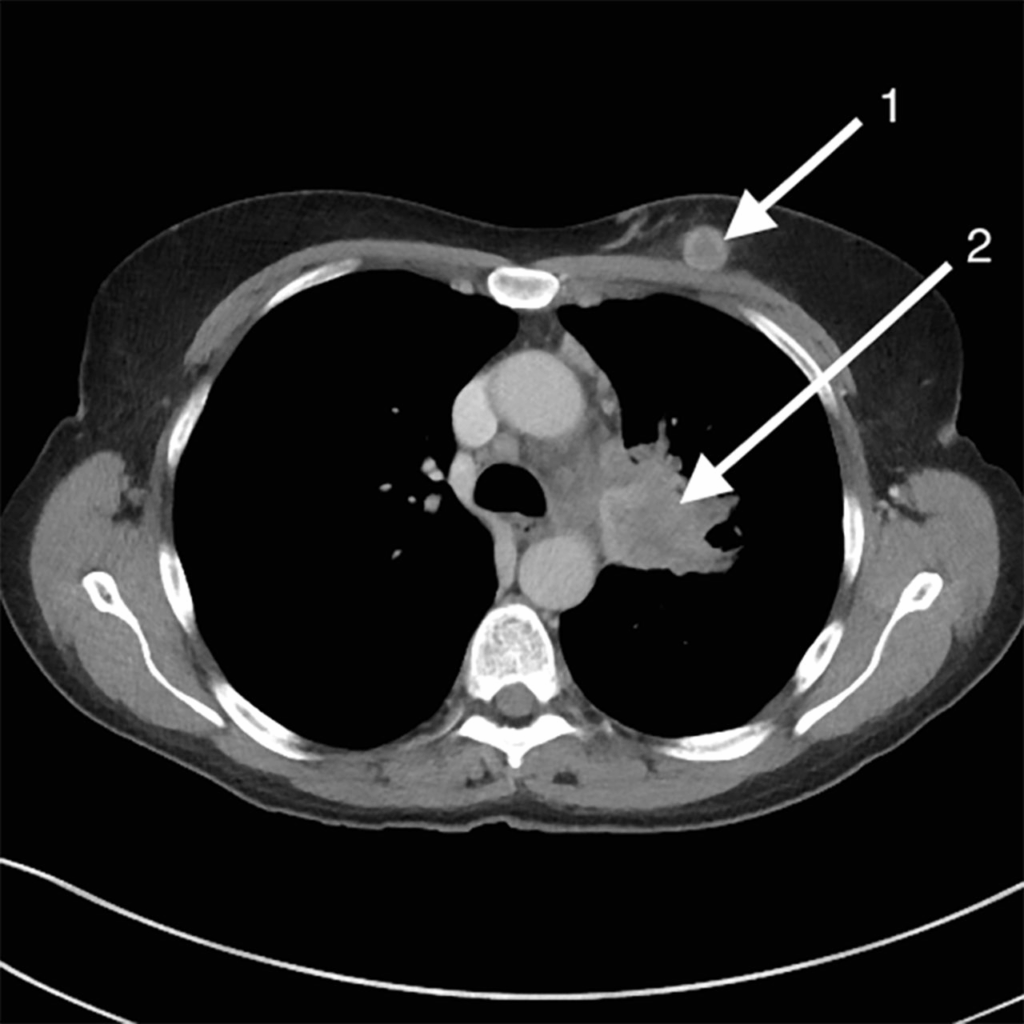

Role of Imaging in Detecting Breast Metastasis from Lung Cancer

Imaging plays a pivotal role in the initial detection and ongoing monitoring of breast metastases. Mammography may show a round, well-defined mass lacking the classic hallmarks of primary breast tumors. Ultrasound imaging often reveals hypoechoic lesions with minimal posterior acoustic shadowing. However, these findings are not specific. Advanced imaging modalities such as contrast-enhanced MRI and PET/CT scans offer higher sensitivity. PET/CT, in particular, is valuable for identifying multiple metastatic sites simultaneously, providing a more comprehensive view of disease spread. Functional imaging also assists in assessing treatment response over time. Furthermore, serial imaging helps determine whether a breast lesion changes in morphology or metabolic activity, which can reflect progression or treatment efficacy. For clinicians, combining imaging and histopathological data is essential for devising the most accurate and individualized treatment plan.

Histopathological Findings and Biomarkers in Confirmation

Histopathological examination confirms the diagnosis and origin of the metastatic lesion. Under the microscope, breast metastases from lung cancer typically preserve their primary tumor characteristics, such as glandular formations in adenocarcinomas. The absence of an in situ component is a key indicator favoring metastatic disease. Immunohistochemistry is instrumental in distinguishing metastatic lung carcinoma from primary breast cancer. TTF-1 and Napsin A are frequently expressed in lung-origin tumors, while breast carcinomas usually express estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER/PR), as well as HER2. The pattern of cytokeratin staining (e.g., CK7 positive/CK20 negative) also supports diagnosis. Molecular profiling may be employed to detect mutations in EGFR, ALK, or KRAS, which can further confirm lung origin and guide targeted therapy decisions. These diagnostic elements are also integral in research on rare skin and hair conditions such as pili multigemini cancer, which similarly require precise histological distinction.

Treatment Approaches: Systemic and Localized Options

Treatment for breast metastases originating from lung cancer is generally systemic, as these lesions indicate advanced disease. Chemotherapy remains the cornerstone for managing metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, with regimens selected based on histological subtype and genetic profile. Targeted therapies, such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors for EGFR or ALK mutations, have significantly improved survival and quality of life in eligible patients. Immunotherapy, particularly checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 or PD-L1, is now standard in many cases and may also impact response in metastatic breast lesions. Localized treatments such as radiation therapy may be used to control painful or progressive breast masses. Surgical excision is not commonly performed unless the mass becomes ulcerated or causes substantial discomfort. A multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists ensures comprehensive care tailored to individual clinical scenarios. This integration of systemic and focal strategies mirrors frameworks used in assessing rare cancer imaging signs, including those in early eyelid malignancies.

Prognosis and Survival Rates in Patients with Breast Metastases from Lung Cancer

When lung cancer metastasizes to the breast, it typically signifies an advanced stage with a generally poor prognosis. Survival rates are influenced by the histologic subtype of lung cancer, the burden and number of metastatic sites, the patient’s performance status, and the responsiveness of the disease to treatment. In most cases, patients with breast metastases also have dissemination to other organs such as the brain, liver, adrenal glands, or bones, compounding the complexity of care. While data is limited due to the rarity of breast metastasis from lung origin, retrospective case series suggest that median survival after diagnosis of breast involvement ranges from 6 to 12 months. Treatment advances, such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy, may extend survival in certain molecularly defined subgroups. However, the goal often shifts toward disease control and quality of life rather than curative intent, as seen in advanced-stage extrapulmonary metastasis scenarios.

Hormone Receptors and HER2 Expression in Breast Metastasis from Lung Cancer

Unlike primary breast tumors, which often express hormone receptors like estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR), metastatic lesions from lung cancer typically lack these receptors. This difference is crucial, as it changes the therapeutic approach. HER2 expression is also uncommon in lung cancer metastases. However, overlap in certain markers, especially in poorly differentiated tumors, can lead to diagnostic confusion. Immunohistochemistry helps clarify this distinction by identifying markers such as TTF-1 and Napsin A, which point toward a pulmonary origin. These results guide oncologists away from using hormone therapy and toward systemic treatments appropriate for lung cancer. Recognizing these biomarker patterns also parallels approaches in other atypical presentations, such as metabolic imbalances explored in the context of can cancer cause low phosphate levels, where nuanced lab interpretation is equally vital.

Patient-Centered Care and Palliative Considerations

When lung cancer has metastasized to uncommon locations like the breast, the treatment trajectory must consider the patient’s overall goals of care, preferences, and quality of life. Many patients at this stage experience fatigue, pain, anxiety, and emotional distress. The emphasis of care often shifts toward palliative interventions that prioritize comfort over aggressive therapy. This may include symptom control with analgesics, psychological support, nutritional guidance, and hospice planning. Open discussions about prognosis and expectations are critical, as are shared decision-making processes that involve family and caregivers. Multidisciplinary palliative teams—including oncologists, nurses, social workers, and chaplains—are instrumental in supporting both patient and family. Such approaches mirror those used in veterinary oncology, especially in end-stage cases addressed in alternative cancer treatments for dogs, where comfort-focused care is prioritized.

Key Differences Between Primary Breast Cancer and Lung Cancer Metastasis

| Feature | Primary Breast Cancer | Metastasis from Lung Cancer |

| Origin | Breast epithelial cells | Pulmonary epithelial cells |

| Typical Age of Onset | 50s–60s | 60s–70s (advanced stage lung cancer) |

| Hormone Receptor Status | Often ER+/PR+, sometimes HER2+ | Usually ER−/PR−/HER2−, often TTF-1+ |

| Radiologic Features | Spiculated mass, calcifications | Well-defined, non-calcified, round nodules |

| Histology | Ductal or lobular carcinoma | Adenocarcinoma or small cell carcinoma |

| In Situ Component | Common | Rare or absent |

| Treatment Approach | Surgery, radiation, hormone therapy | Systemic chemo, targeted agents, immunotherapy |

| Prognosis | Variable, depending on stage | Generally poor, palliative intent |

Impact of Lung Cancer Subtype on Breast Metastatic Behavior

The primary histological subtype of lung cancer plays a significant role in determining whether and how the disease may metastasize to the breast. Non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC), especially adenocarcinomas, have shown a slightly higher tendency to spread to distant soft tissues compared to small cell lung cancer (SCLC), which more commonly spreads to the brain, bone, and liver. Adenocarcinoma subtypes are characterized by peripherally located primary tumors, increasing the chance of hematogenous dissemination, including rare sites like the breast. On the other hand, squamous cell carcinomas of the lung rarely involve breast tissue. The subtype influences both diagnostic expectations and treatment strategy. Targetable mutations such as EGFR, ALK, or ROS1—frequently found in adenocarcinomas—guide oncologists toward precision therapies, whereas triple-negative or wild-type profiles leave fewer options, especially when dealing with unusual metastatic locations.

Role of Biopsy and Immunohistochemistry in Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of breast metastasis originating from lung cancer hinges on a biopsy of the breast lesion, accompanied by a thorough histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Core needle biopsy is preferred as it yields enough tissue for detailed evaluation. Pathologists examine the morphology under microscopy to differentiate it from primary breast carcinoma. Key immunomarkers are pivotal in this process. Positive expression of TTF-1 (thyroid transcription factor-1) and Napsin A are highly indicative of pulmonary origin. Negative hormone receptors and HER2 further differentiate it from breast primary. In rare cases where markers are ambiguous, additional testing such as CK7, CK20, and molecular profiling may be required. The diagnostic rigor here mirrors similar challenges faced in rare skin-hair conditions like pili multigemini cancer, where precise cellular analysis is required to rule out malignancy.

Treatment Outcomes and Emerging Research

While treatment of metastatic lung cancer to the breast remains palliative in most cases, ongoing research is exploring novel therapeutic avenues that may improve outcomes. Immunotherapy with checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab has revolutionized lung cancer care, especially for tumors expressing PD-L1. Additionally, targeted therapy continues to evolve with next-generation inhibitors for EGFR, ALK, and MET. Researchers are also investigating combinations of immunotherapy with chemotherapy or anti-angiogenic agents. Clinical trials are increasingly open to patients with atypical metastatic sites, including breast involvement. Despite promising advances, individual responses vary greatly, and real-world data on breast-specific metastasis remains scarce. Still, the broader understanding of metastatic patterns, similar to what we learn from gastrointestinal malignancies like early stage eyelid cancer pictures, is pushing forward the need for personalized medicine approaches.

Psychosocial Support for Patients with Rare Metastases

Receiving a diagnosis of lung cancer with metastasis to the breast can be deeply distressing for patients, especially when compounded by the rarity of such a presentation. The psychological burden often includes fear, uncertainty, grief, and a sense of isolation. Effective cancer care must therefore extend beyond pharmacologic treatment and incorporate psychosocial support systems. Oncology social workers, support groups, therapists, and peer networks play critical roles in helping patients process the emotional weight of diagnosis and prognosis. Some patients benefit from narrative therapy or expressive arts, while others may find strength in structured education programs that demystify the science behind their condition. Navigating such rare presentations often mirrors the anxiety faced by patients in unusual disease contexts such as low-phosphate syndromes or off-label therapy scenarios. Comprehensive care includes not just the body, but the mind and spirit of the patient.

FAQ

What makes breast metastasis from lung cancer so rare?

Metastasis of lung cancer to the breast is rare because breast tissue is not a typical site for secondary tumors. Most metastases from lung cancer go to the brain, bones, liver, or adrenal glands. The breast’s unique microenvironment, dense fibroglandular structure, and lower vascular density compared to other organs make it a less favorable location for circulating tumor cells to colonize and thrive.

How is metastatic lung cancer to the breast diagnosed?

Diagnosis begins with imaging, such as mammography or ultrasound, when a breast mass is detected. However, confirmation requires a tissue biopsy, followed by immunohistochemical staining. Markers like TTF-1 and Napsin A suggest lung origin, while absence of hormone receptors can help rule out primary breast cancer, leading to a conclusive diagnosis.

Are symptoms different from primary breast cancer?

Yes, symptoms often differ. Metastatic lung cancer to the breast usually presents as a painless, rapidly growing mass without skin changes or nipple retraction, which are more common in primary breast cancer. It may also be located in unusual parts of the breast and be less likely to involve axillary lymph nodes initially.

Can lung cancer metastasize to only one breast?

It can, and typically does. Most reported cases involve unilateral breast metastasis, although bilateral involvement has occurred. The unilateral pattern aligns with hematogenous (bloodborne) spread, in contrast to lymphatic spread typical of primary breast malignancies.

Does metastasis to the breast mean the cancer is terminal?

While breast metastasis indicates stage IV disease, it doesn’t automatically mean the patient has no treatment options or is at immediate risk of death. Outcomes depend on various factors such as the tumor’s molecular profile, patient health, response to therapy, and access to emerging treatments like immunotherapy or targeted therapy.

What imaging is most effective for detecting breast metastasis?

Ultrasound and mammography can detect the presence of a mass, but they often cannot distinguish metastatic lesions from primary tumors. MRI provides additional detail and helps define the extent of involvement. PET-CT is particularly useful in staging, revealing both the breast lesion and distant sites of disease.

Is surgery an option for treating metastatic lesions in the breast?

Surgery is not typically curative for metastatic breast lesions, but in selected cases it may be performed for diagnostic clarity or symptom relief. The focus remains systemic therapy, as the underlying disease is already disseminated. Surgery might be considered if the lesion causes discomfort or ulceration.

How do doctors distinguish lung-to-breast metastasis from breast-to-lung spread?

Pathologists rely on tumor markers and histological patterns. Lung cancer metastasis to the breast expresses markers like TTF-1 and Napsin A, while primary breast cancers may show ER, PR, or HER2 positivity. A detailed patient history, imaging, and molecular workup guide the accurate origin determination.

What are the treatment options for patients with breast metastasis from lung cancer?

Systemic treatments are the standard, including chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. These depend on the cancer’s specific genetic mutations, such as EGFR or ALK alterations. Hormone therapies are generally ineffective unless the tumor expresses hormone receptors, which is rare in this setting.

Can immunotherapy be effective in such cases?

Yes, immunotherapy—especially PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors like pembrolizumab—can be effective for non-small cell lung cancers that express PD-L1. Success depends on the tumor’s immune landscape. Even in unusual metastatic sites like the breast, these therapies have shown promising responses in eligible patients.

Is radiation therapy used for breast metastases?

Radiation therapy may be used palliatively if the metastasis is painful, ulcerated, or at risk of bleeding. It’s not typically used with curative intent, but it can offer local control and symptom relief in cases where systemic therapies alone are insufficient.

Are certain lung cancer subtypes more likely to spread to the breast?

Adenocarcinoma, a subtype of non-small cell lung cancer, has been most frequently reported in cases of breast metastasis. Its molecular behavior and peripheral lung origin may contribute to its ability to spread via the bloodstream to distant sites like breast tissue.

How is patient quality of life addressed during treatment?

Quality of life is managed through a combination of symptom control, supportive therapies, and psychosocial care. Oncology teams often include social workers, psychologists, palliative care specialists, and pain management experts to help patients maintain comfort and emotional well-being throughout treatment.

Is genetic testing helpful in these cases?

Absolutely. Genetic profiling can uncover actionable mutations such as EGFR, ALK, ROS1, or MET, which guide treatment with targeted therapies. In rare metastatic cases, this testing becomes even more important, as traditional treatment approaches may be less effective or too toxic.

Where can patients find support for rare cancer presentations?

Patients can turn to national cancer support organizations, rare cancer registries, and online communities for connection and resources. Institutions that specialize in thoracic oncology often have multidisciplinary teams and trial access. Peer networks and clinical trial databases can offer additional pathways for help and hope.