Understanding Fainting Spells (Syncope): From Causes to Clinical Management

Clinical Overview of Fainting Spells

Definition and Scope

Fainting, medically known as syncope, is a sudden and brief loss of consciousness caused by a temporary reduction in blood flow to the brain. This transient decrease in cerebral perfusion interrupts normal brain function for a few seconds, leading to collapse followed by spontaneous and complete recovery. Syncope differs from other transient losses of consciousness such as seizures or metabolic disturbances because it arises from circulatory rather than neurological dysfunction.

Clinically, understanding fainting spells begins with recognizing them as a physiologic response rather than a disease. They may occur in otherwise healthy individuals or in the context of serious cardiovascular disorders, requiring careful evaluation to determine the underlying cause.

- Key distinction: Circulatory rather than neurological origin.

- Duration: Brief loss of consciousness with full recovery.

- Clinical importance: A common symptom that may signal underlying cardiac or autonomic dysfunction.

How Fainting Occurs

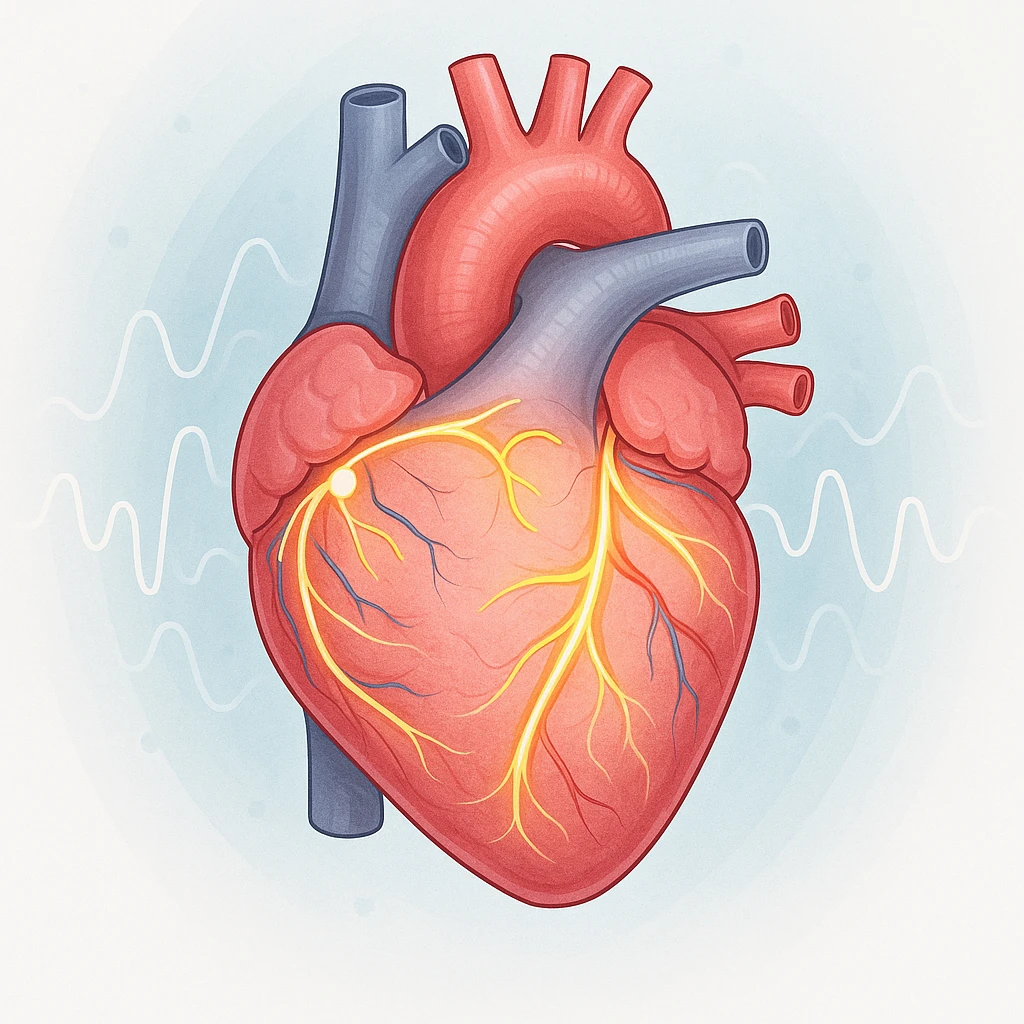

The body’s ability to maintain consciousness depends on a steady blood supply to the brain. When this balance is disrupted, even briefly, fainting can occur. In many cases-particularly vasovagal syncope-the body’s autonomic reflexes cause blood vessels to widen (vasodilation) and the heart rate to slow (bradycardia). These changes lower blood pressure and cardiac output, momentarily decreasing brain perfusion.

Before a fainting episode, subtle physiological changes occur, including pooling of blood in the lower extremities, reduced venous return to the heart, and compensatory but sometimes insufficient autonomic adjustments. The result is transient global cerebral hypoperfusion, a reversible state that resolves quickly once the person becomes horizontal and blood flow normalizes.

Clinical Relevance

Syncope is a frequent reason for emergency and outpatient visits. Despite its prevalence, it often remains undiagnosed after initial evaluation due to varied triggers and mechanisms. Recognizing fainting spells as possible indicators of cardiovascular or autonomic instability is essential for proper risk assessment and determining when further testing is required.

For patients, understanding how fainting occurs can reduce anxiety and promote informed management. Differentiating benign episodes from those associated with heart disease or other high-risk conditions is crucial for improving outcomes and preventing recurrences.

Causes and Types of Fainting Spells

Fainting spells can arise from several distinct physiological mechanisms. Understanding these causes is key to identifying which episodes are benign and which may signal serious cardiovascular disease. The three principal categories are reflex syncope, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac syncope, each representing a different pathway that leads to temporary cerebral hypoperfusion and loss of consciousness.

- Reflex syncope: Triggered by autonomic reflexes that cause vasodilation or bradycardia.

- Orthostatic hypotension: Results from failure to maintain blood pressure upon standing.

- Cardiac syncope: Arises from arrhythmias or structural heart disease that reduce blood flow.

Reflex Syncope

Reflex syncope, also called neurally mediated or vasovagal syncope, is the most common and generally benign type. It occurs when an inappropriate autonomic reflex triggers sudden vasodilation and/or a slowing of the heart rate (bradycardia). Common triggers include emotional stress, pain, or prolonged standing, all of which overstimulate the vagus nerve and disturb circulatory control.

- Vasovagal syncope: Triggered by emotional stress, pain, or prolonged standing.

- Situational syncope: Occurs during actions such as coughing, swallowing, or urination.

- Carotid sinus syncope: Caused by neck pressure activating carotid baroreceptors.

Despite its dramatic presentation, reflex syncope usually resolves spontaneously and has a good prognosis when structural heart disease is absent.

Orthostatic Hypotension

Orthostatic hypotension involves a sustained drop in blood pressure when moving from lying or sitting to standing. This occurs when the autonomic or vascular responses that maintain blood pressure fail. Causes include dehydration, blood loss, medications, or autonomic dysfunction. The resulting reduced venous return and cardiac output decrease brain perfusion, leading to dizziness or fainting.

Orthostatic hypotension is often chronic or recurrent, reflecting impaired volume regulation or autonomic control rather than a sudden reflex. Management typically focuses on correcting underlying causes or adjusting medications.

Cardiac Syncope

Cardiac syncope results from disorders that impair the heart’s ability to sustain adequate cardiac output. It may stem from arrhythmias-such as bradyarrhythmias or tachyarrhythmias-or from structural or obstructive lesions that restrict blood flow. Conditions like aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or pulmonary embolism can sharply reduce blood flow to the brain, leading to sudden and potentially dangerous fainting spells.

| Type | Main Mechanism | Typical Triggers | Clinical Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reflex Syncope | Autonomic reflex causing vasodilation and/or bradycardia | Emotional stress, pain, standing | Usually benign |

| Orthostatic Hypotension | Failure to maintain blood pressure on standing | Postural change, dehydration, medications | Low to moderate |

| Cardiac Syncope | Arrhythmia or structural heart disease reducing cardiac output | Exertion, lying down, cardiac disease | High, potentially life-threatening |

Cardiac syncope carries the highest risk for morbidity and mortality. Because it can indicate life-threatening arrhythmias or structural heart disease, rapid recognition and evaluation are critical for effective treatment.

Recognizing Warning Signs and Risk Factors

Recognizing early warning signs and risk factors is vital to distinguishing benign fainting spells from those with cardiac origins. A thorough evaluation clarifies the mechanism and severity, ensuring that at-risk patients receive timely medical attention.

Prodromal and Trigger Patterns

Before fainting, many individuals experience prodromal symptoms offering diagnostic clues. Common warning signs include:

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Nausea or feeling of warmth

- Blurred or dimmed vision

- Weakness or sweating

These symptoms often occur with triggers such as heat exposure, emotional stress, or prolonged standing-typical of reflex or vasovagal syncope. Conversely, fainting without warning, especially during exertion or while lying down, may signal cardiac causes.

Red Flags for High-Risk Syncope

High-risk indicators requiring immediate evaluation:

- Known or suspected structural heart disease

- Abnormal findings on a 12-lead ECG

- Syncope during exertion or while supine

- Family history of sudden cardiac death

The presence of these features increases the likelihood of cardiac or arrhythmic causes and warrants hospital monitoring or urgent cardiac assessment.

Risk Stratification in Practice

Risk assessment for syncope relies on detailed history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests such as orthostatic blood pressure measurement and a 12-lead ECG. These establish whether the event is likely benign or serious.

| Assessment Step | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Detailed History | Identify triggers, context, and prodromal symptoms |

| Physical Examination | Detect structural or autonomic abnormalities |

| Orthostatic Blood Pressure | Evaluate for orthostatic hypotension |

| 12-Lead ECG | Screen for arrhythmias or conduction disorders |

Patients with low-risk features and identifiable reflex triggers are typically managed outpatient, while those with cardiac findings may need inpatient observation to ensure safety and accurate diagnosis.

Diagnostic Approach and Specialized Testing

When the cause of fainting spells is unclear after initial evaluation, targeted diagnostic tests clarify the underlying mechanism. These tests are guided by history, physical findings, and ECG results to distinguish reflex, orthostatic, and cardiac causes.

Tilt-Table and Reflex Testing

Tilt-table testing is an important diagnostic tool for suspected reflex (vasovagal) syncope or autonomic dysfunction. During this test, the patient is placed upright at a controlled angle while heart rate and blood pressure are monitored, simulating the effects of standing. This helps clinicians observe abnormal autonomic responses such as vasodilation or bradycardia and confirm the diagnosis safely.

- Purpose: Identify abnormal autonomic responses causing fainting.

- Procedure: Patient positioned upright at a controlled angle with continuous monitoring.

- Clinical value: Confirms reflex syncope when other evaluations are inconclusive.

Additional autonomic assessments, including carotid sinus massage or Valsalva maneuver analysis, may be performed in selected patients to document exaggerated cardiovascular reflexes linked to recurrent fainting.

Cardiac Imaging and Monitoring

When cardiac syncope is suspected based on history or ECG, imaging and rhythm monitoring become essential. Echocardiography reveals structural abnormalities such as valvular stenosis or cardiomyopathy, helping distinguish high-risk cardiac causes from benign fainting spells.

| Test | Main Purpose | When Used |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | Visualizes heart structure and function | Suspected structural heart disease or obstruction |

| Holter Monitor | Records heart rhythm for 24-48 hours | Frequent fainting or intermittent arrhythmia |

| Implantable Loop Recorder | Provides long-term rhythm monitoring | Infrequent but unexplained syncope episodes |

Ambulatory monitoring captures transient arrhythmias that short-term ECGs may miss. While Holter monitors aid frequent episodes, loop recorders detect rare but severe events, allowing correlation between symptoms and cardiac rhythm for accurate diagnosis.

Managing and Preventing Fainting Spells

Management of fainting spells, or syncope, depends on identifying the underlying cause. Because mechanisms vary-from benign reflex responses to potentially serious cardiac conditions-treatment must be tailored to the specific type. While most fainting episodes are self-limited, appropriate management and preventive measures can reduce recurrence and improve safety.

Treatment by Syncope Type

For reflex or vasovagal syncope, conservative strategies form the cornerstone of management. Patient education and reassurance are essential, focusing on recognizing early warning signs and avoiding known triggers such as dehydration, heat exposure, or standing for long periods. Increasing fluid and salt intake can help stabilize circulation. Physical counter-pressure maneuvers-such as leg crossing or tensing muscles at symptom onset-may maintain blood pressure and prevent fainting.

- Reflex/Vasovagal Syncope: Education, trigger avoidance, hydration, and counter-pressure maneuvers.

- Orthostatic Hypotension: Volume optimization and medication adjustment to stabilize blood pressure.

- Cardiac Syncope: Targeted treatment including pacemaker placement, ablation, or surgical correction of structural abnormalities.

Cardiac syncope, by contrast, requires targeted treatment of the underlying cardiac disorder. When arrhythmia is the cause, therapies may include pacemaker implantation for bradyarrhythmias or ablation for tachyarrhythmias. Structural heart disease may require surgical or interventional correction. Because cardiac syncope carries a higher risk of serious outcomes, early identification and specialized management are essential.

Prevention and Lifestyle Measures

Preventing fainting spells centers on managing predisposing factors and reinforcing behavioral measures. Maintaining adequate hydration and regular meals supports blood pressure and reduces the likelihood of orthostatic drops. Patients should rise gradually from sitting or lying positions and avoid prolonged standing. In recurrent reflex syncope, recognizing premonitory symptoms such as dizziness or nausea and lying down promptly can prevent full loss of consciousness.

- Stay well hydrated and maintain electrolyte balance.

- Rise slowly from sitting or lying positions.

- Recognize and respond to early warning signs like dizziness.

- Review medications that may affect blood pressure or circulation.

- Plan safe activities, especially in hot or crowded environments.

Medication review and safe activity planning can significantly lower recurrence rates, particularly in older adults or those on blood pressure-lowering drugs. For patients with frequent or unexplained fainting spells, continued follow-up helps detect pattern changes or emerging cardiac signs promptly.

Prognosis and Follow-Up

| Syncope Type | Typical Prognosis | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reflex Syncope | Excellent, with low mortality | Usually self-limited; managed with education and lifestyle changes. |

| Orthostatic Hypotension | Variable, often chronic | Requires ongoing management of volume status and medication review. |

| Cardiac Syncope | Higher short- and long-term mortality | Needs close monitoring and treatment for arrhythmia or structural disease. |

The prognosis for fainting depends on the cause. Reflex syncope generally has an excellent outlook with minimal long-term health impact and low mortality. Most patients recover quickly and can manage recurrences with lifestyle strategies. Orthostatic hypotension may persist but is typically controllable with hydration and medication adjustments.

Cardiac syncope, however, is associated with higher short- and long-term mortality due to the risk of sudden cardiac death. Regular follow-up and cardiac monitoring are essential to evaluate treatment effectiveness and detect new arrhythmias or disease progression early. A structured and individualized approach allows most patients to achieve good symptom control and improved quality of life.