Understanding Colon Cancer with Stomach Wall Metastasis: A Detailed Guide for Patients and Families

- Introduction: The Complexity of Metastatic Colon Cancer

- Mechanism of Metastasis from Colon to Stomach Wall

- Clinical Symptoms When Colon Cancer Reaches the Stomach Wall

- Diagnosing Stomach Wall Metastasis in Colon Cancer Patients

- Differences Between Primary Stomach Cancer and Metastatic Colon Cancer to the Stomach Wall

- Systemic Treatment Options for Stomach Wall Metastasis

- Surgical Intervention in Selected Cases

- Palliative Care and Symptom Management

- Prognosis for Patients with Colon Cancer Spread to the Stomach Wall

- Differences Between Peritoneal Carcinomatosis and Stomach Wall Metastasis

- Nutritional Management During Treatment

- Strategies for Maintaining Caloric Intake

- Monitoring Response to Treatment and Disease Progression

- The Role of Clinical Trials in Advanced-Stage Colon Cancer

- Psychological Support for Patients and Families

- Hospice and End-of-Life Considerations

- Managing a Complex and Rare Metastasis with Comprehensive Care

- FAQ: Colon Cancer Metastasized to the Stomach Wall

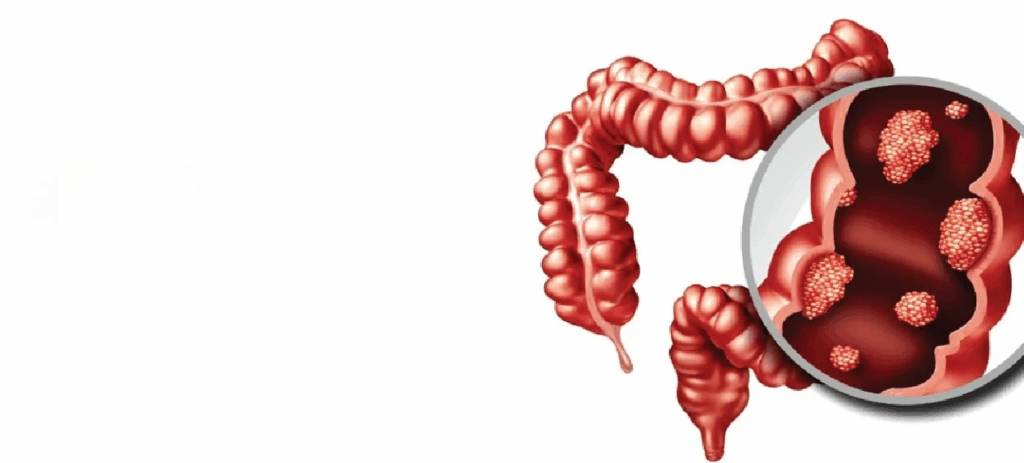

Introduction: The Complexity of Metastatic Colon Cancer

Colon cancer is one of the most common malignancies worldwide, but when it spreads beyond the colon, especially to atypical sites like the stomach wall, it presents unique challenges. The condition—known as metastatic colon cancer—typically spreads to the liver, lungs, or peritoneum, but stomach wall involvement is rare and often misdiagnosed or detected late. This progression indicates advanced-stage disease and requires highly individualized care.

Metastasis to the stomach wall usually occurs through hematogenous spread, lymphatic invasion, or peritoneal seeding. When cancer cells settle in the stomach lining, they may mimic primary gastric cancer in appearance, making diagnosis complex. Recognizing this pattern is crucial for selecting the right treatment strategy, which often involves a combination of systemic chemotherapy, targeted agents, and supportive care.

Mechanism of Metastasis from Colon to Stomach Wall

Biological Pathways of Tumor Spread

Colon cancer cells can leave the primary site through the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Once in circulation, these cells may travel to distant tissues, including the stomach. The stomach wall—composed of mucosa, submucosa, muscle, and serosa—can serve as a fertile ground for implantation, especially if immune surveillance is compromised.

Another route involves peritoneal spread, where cancer cells exfoliate into the abdominal cavity and attach to nearby surfaces, including the gastric serosa. Over time, these cells can invade deeper stomach layers, causing symptoms and structural changes. While liver and lung metastases are more common, gastric metastasis is increasingly recognized in advanced colorectal cancer.

Molecular Characteristics of Aggressive Tumors

Certain genetic and molecular features in colorectal cancer increase the likelihood of atypical metastasis. Mutations in KRAS, BRAF, or TP53, as well as microsatellite instability (MSI), correlate with aggressive tumor behavior and a higher tendency to spread beyond traditional boundaries. Tumors with these markers may bypass the liver or lungs entirely and spread to unusual locations like the stomach, bones, or brain. See “can accutane cause cancer” in the context of the influence of genetic mutations and chemicals on cell behavior.

Clinical Symptoms When Colon Cancer Reaches the Stomach Wall

Overlapping and Unique Presentations

Patients with colon cancer that has metastasized to the stomach wall may experience a combination of gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms. Early signs often overlap with primary stomach conditions, which leads to delayed recognition. Nausea, early satiety, bloating, and upper abdominal pain are frequent complaints. These symptoms arise due to infiltration of the gastric wall, reduced motility, and eventual obstruction.

In more advanced cases, patients might develop vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, or significant weight loss. Because these symptoms mimic peptic ulcers or gastritis, a full diagnostic workup is required to confirm metastatic origin. When accompanied by fatigue, anemia, and a known history of colon cancer, the suspicion should be high for metastatic involvement.

Physical and Nutritional Decline

The presence of cancer in the stomach wall often compromises nutrient absorption and food tolerance. As eating becomes painful or inefficient, patients may involuntarily reduce food intake, leading to cachexia—a syndrome of weight loss, muscle wasting, and systemic weakness. This decline affects not just the gastrointestinal system but also overall immune response and treatment tolerance.

Diagnosing Stomach Wall Metastasis in Colon Cancer Patients

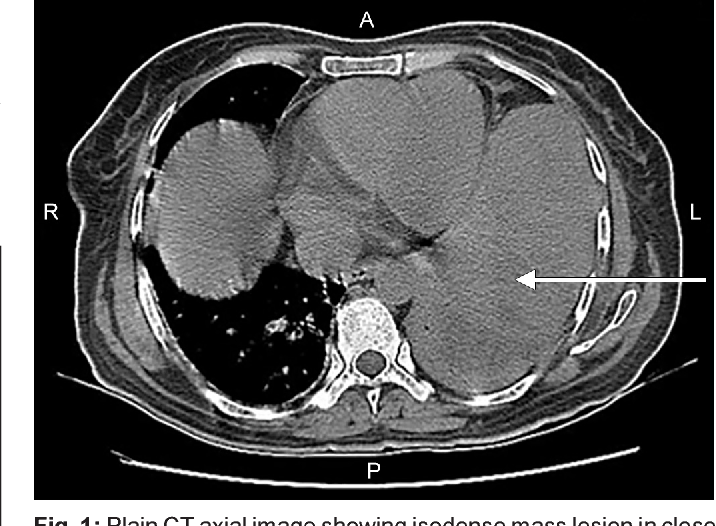

Diagnostic Imaging and Biopsy Protocols

Accurate diagnosis requires a combination of imaging and histological confirmation. Contrast-enhanced CT scans can reveal thickening of the stomach wall, but such findings are non-specific. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provides better resolution for assessing the depth of invasion and guiding biopsy. Positron emission tomography (PET) may be used to evaluate the metabolic activity of suspicious lesions.

Upper GI endoscopy is the most definitive method for identifying lesions in the stomach wall. During the procedure, a gastroenterologist visually inspects the mucosal surface and takes biopsies. Histopathological analysis confirms whether the tissue is consistent with metastatic colorectal origin rather than primary gastric carcinoma.

Role of Immunohistochemistry and Genetic Markers

Distinguishing a metastatic lesion from a primary stomach tumor often requires immunohistochemical staining. Markers such as CK20, CDX2, and SATB2 are typically positive in colorectal origin, while gastric cancers express CK7 or HER2 more frequently. Molecular profiling helps in not only confirming the diagnosis but also tailoring targeted therapy options. Salivary gland cancer in dogs as an example of an oncological diagnosis where it is critically important to distinguish between the primary and metastatic nature of the tumor.

Differences Between Primary Stomach Cancer and Metastatic Colon Cancer to the Stomach Wall

Clinical and Histological Contrasts

Although primary stomach cancer and metastatic colon cancer to the stomach wall may produce similar symptoms—such as abdominal pain, nausea, or GI bleeding—their origins and microscopic structures differ significantly. Primary gastric adenocarcinomas usually arise from the stomach’s mucosal lining and show features consistent with gland-forming carcinoma. In contrast, metastasis from colon cancer typically presents with well-formed glandular structures that resemble colonic histology.

Histopathology often reveals cleaner demarcation in metastases, and the surrounding gastric tissue may appear unaffected until deeper layers are invaded. In primary cancers, mucosal changes and ulcerations tend to be more extensive. Knowing the source of the malignancy is crucial because treatment protocols vary significantly based on origin.

Implications for Treatment and Prognosis

Therapeutic strategies for metastatic lesions focus on the primary cancer’s biology and behavior. For instance, a metastatic lesion in the stomach wall from colorectal origin may respond well to chemotherapy regimens like FOLFOX or FOLFIRI, whereas primary gastric cancer may require HER2-targeted therapy or entirely different agents. The distinction not only affects drug choice but also prognosis, as metastatic colon cancer generally carries a more advanced stage designation, even if limited in location.

Systemic Treatment Options for Stomach Wall Metastasis

First-Line Chemotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy remains the foundation of treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer, including cases with gastric involvement. Standard regimens include combinations such as FOLFOX (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin) and FOLFIRI (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan), often combined with targeted therapies. Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, or cetuximab/panitumumab (anti-EGFR agents) may be added depending on tumor genetic profiles.

Because the stomach wall is a relatively rare site of metastasis, data on direct treatment outcomes are limited. However, patients with isolated or oligometastatic involvement often experience symptom relief and tumor shrinkage when systemic therapy is started promptly and tailored to molecular markers.

Role of Targeted and Immunotherapy

Genomic testing plays an increasingly important role in selecting advanced therapies. For example, tumors with microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) may respond well to immunotherapy agents such as pembrolizumab. Meanwhile, KRAS or BRAF mutations dictate the use or exclusion of EGFR inhibitors.

Although not all metastatic colon cancers qualify for these advanced options, their presence has significantly improved survival in selected patients. Personalized therapy is now the standard approach, especially in metastatic disease with uncommon spread patterns like stomach wall involvement.

Surgical Intervention in Selected Cases

Indications for Surgery

Surgery is generally not the first choice for metastatic colon cancer with gastric involvement, but in carefully selected patients, it may provide palliation or prolong survival. Indications include gastric outlet obstruction, uncontrollable bleeding, or perforation caused by the metastasis. In such cases, partial gastrectomy or bypass procedures may be required to restore gastrointestinal function.

In rare situations where metastasis is limited and systemic disease is well-controlled, surgical removal of the stomach wall lesion along with the primary tumor and other metastases might be considered. This is typically only offered at specialized cancer centers and within the context of multidisciplinary evaluation.

Risks and Postoperative Considerations

Gastric surgery in metastatic cancer patients carries elevated risks, including infection, delayed healing, and nutritional compromise. Moreover, recovery may be complicated by concurrent chemotherapy or frailty due to cancer cachexia. A comprehensive risk-benefit discussion is essential before proceeding.

Patients undergoing surgery often need nutritional support via enteral or parenteral feeding and frequent follow-up to monitor healing and disease status. The ultimate decision must be guided by prognosis, performance status, and overall goals of care.

Palliative Care and Symptom Management

Symptom-Focused Approaches

For many patients with metastatic colon cancer to the stomach wall, especially those with widespread disease, the focus shifts to quality of life. Palliative care aims to relieve symptoms such as nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting, and fatigue. Proton pump inhibitors may be used to reduce gastric acid and bleeding, while antiemetics help manage nausea from both the cancer and chemotherapy.

Nutritional counseling is also vital, as patients often struggle with reduced appetite or early satiety. Small, frequent meals and supplementation with high-calorie, high-protein drinks are common strategies. In severe cases, feeding tubes or intravenous nutrition may be necessary to maintain strength.

Psychosocial and Emotional Support

Living with metastatic cancer can take a significant toll on mental health. Anxiety, depression, and emotional distress are common, especially when eating becomes a source of discomfort or fear. Oncology teams often involve counselors, support groups, and palliative care specialists to help patients and families cope. Ensuring emotional support is as critical as managing physical symptoms. bph vs prostate cancer psa levels in the context of the importance of monitoring patients with a long-term oncological diagnosis, where treatment extends beyond one organ.

Prognosis for Patients with Colon Cancer Spread to the Stomach Wall

Factors That Influence Prognosis

Prognosis for metastatic colon cancer involving the stomach wall depends on a complex interplay of variables. Tumor burden, genetic markers, response to therapy, and overall health status are key predictors. Patients whose disease is limited to a few metastatic sites and who respond well to chemotherapy tend to have better outcomes than those with extensive systemic involvement or aggressive molecular profiles.

Microsatellite instability and lack of KRAS/BRAF mutations are associated with more favorable responses to targeted or immunotherapies, which can extend progression-free survival significantly. However, even with modern treatments, stomach wall metastasis generally signifies stage IV disease, which lowers long-term survival probability.

Survival Expectations and Realistic Outcomes

While median survival for metastatic colon cancer has improved to 24–30 months with combination therapy, involvement of rare sites like the stomach wall may indicate more aggressive disease. If treated aggressively, some patients can achieve durable remission or long-term control, particularly when metastasis is isolated and surgically accessible. Still, clinicians often focus on balancing life extension with preservation of quality of life.

Differences Between Peritoneal Carcinomatosis and Stomach Wall Metastasis

Pathophysiology and Spread Patterns

Peritoneal carcinomatosis involves widespread dissemination of cancer cells across the abdominal cavity’s lining, often creating multiple tumor implants on the surfaces of organs including the stomach, intestines, and omentum. In contrast, stomach wall metastasis from colon cancer usually presents as localized infiltration rather than diffuse peritoneal spread.

These two conditions can coexist, especially in advanced cases, but they require different clinical management strategies. Carcinomatosis may lead to complications like ascites, bowel obstruction, or widespread inflammation, whereas stomach wall involvement tends to affect digestion and gastric motility directly.

Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Treatment for carcinomatosis often includes cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC), a complex but aggressive approach. On the other hand, isolated gastric metastasis may be managed with systemic therapy and selective surgery or radiation. Recognizing the distinction is critical for appropriate staging, prognosis, and therapy design.

Nutritional Management During Treatment

Strategies for Maintaining Caloric Intake

Nutrition becomes a central concern for patients with stomach wall involvement. Difficulty eating, early satiety, nausea, and pain may all lead to malnutrition, which negatively impacts immune function, tolerance to treatment, and recovery. Maintaining caloric intake requires creativity, patience, and professional guidance from oncology dietitians.

Patients are encouraged to eat small, frequent meals rich in protein and calories. Liquid supplements can help bridge the nutritional gap. If oral intake becomes insufficient, feeding tubes (e.g., jejunostomy or PEG) or parenteral nutrition may be required. Nutritional status is assessed regularly and addressed dynamically as disease and treatment evolve.

Avoiding Cachexia and Preserving Muscle Mass

Cachexia, or cancer-induced muscle wasting, is a life-threatening complication in advanced cancer. It cannot be reversed by food alone and often requires anti-inflammatory or anabolic agents in combination with nutritional strategies. Preserving muscle mass through gentle physical activity and supplementation (such as omega-3 fatty acids and amino acids) may reduce functional decline.

Monitoring Response to Treatment and Disease Progression

Imaging and Biomarker Tracking

Monitoring how well the disease responds to therapy is essential in adjusting the treatment plan. Imaging techniques such as CT scans or PET-CT are performed at regular intervals, typically every 2 to 3 months, to evaluate tumor shrinkage or stability. Endoscopy may be repeated if symptoms suggest re-infiltration of the stomach wall or new lesions.

Tumor markers like carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) are also tracked over time. A consistent decline suggests effective treatment, while a rising trend may indicate progression or recurrence. These markers, while not perfect, help guide decision-making alongside imaging and clinical symptoms.

Adjusting Therapy Based on Response

If a patient shows stable disease or partial response, current therapies may be continued. However, progression may prompt a switch to second-line chemotherapy, clinical trials, or best supportive care. Molecular reanalysis may be considered, especially if new mutations emerge that make the cancer eligible for targeted or immunotherapy.

The Role of Clinical Trials in Advanced-Stage Colon Cancer

Accessing Emerging Therapies

For patients with metastatic colon cancer involving the stomach wall, clinical trials may provide access to new treatments not yet available through standard care. These trials explore novel chemotherapy combinations, immunotherapy agents, targeted drugs, and even advanced delivery systems. Participation offers hope, especially for those who have exhausted first- and second-line treatments.

Enrollment criteria vary depending on previous treatments, genetic profiles, and functional status. Patients with specific mutations—such as NTRK fusions, HER2 overexpression, or MSI-H tumors—are often prime candidates for trial therapies showing promising early results. Clinical trial participation is coordinated through cancer centers and academic hospitals with dedicated oncology research departments.

Risks and Considerations

While clinical trials offer potential benefits, they also involve uncertainty. Experimental therapies may not work as intended, or side effects may be more severe than anticipated. Thorough discussions between patients and oncologists are necessary to weigh risks, expectations, and eligibility. For some, trials are a last resort; for others, they represent a proactive step toward innovative care.

Psychological Support for Patients and Families

Emotional Impact of Metastatic Diagnosis

A diagnosis of colon cancer that has spread to the stomach wall often brings a wave of emotional turmoil. Fear, grief, and anxiety are common, not just for patients but also for their families. This emotional weight can interfere with treatment adherence, decision-making, and day-to-day well-being. Psychosocial support is, therefore, an essential component of care.

Psychologists, social workers, and spiritual counselors are often included in oncology teams to provide guidance. Support groups—whether in person or online—help patients connect with others who understand the journey. When available, palliative care specialists can assist in managing not only symptoms but also existential distress.

Communicating with Family and Children

Sharing news of a metastatic diagnosis with loved ones is one of the most difficult tasks patients face. Being honest while maintaining hope is a delicate balance. Children, in particular, need age-appropriate explanations that offer reassurance without creating unnecessary fear. Counseling services can offer support through this process, ensuring communication remains open and emotionally safe.

Hospice and End-of-Life Considerations

When to Transition to Comfort-Focused Care

If colon cancer progresses despite all treatments, or if the burden of side effects becomes intolerable, transitioning to hospice care may be the most compassionate choice. Hospice focuses on comfort and dignity, prioritizing symptom relief over aggressive interventions. This shift does not mean giving up—it means refocusing care on what matters most to the patient.

Hospice services include pain management, nausea control, and emotional support. Care can be provided at home, in hospice centers, or sometimes in hospitals. Many families find that hospice allows them to spend more meaningful time together in a supportive, peaceful environment.

Planning and Legacy

End-of-life planning includes advance directives, choosing a healthcare proxy, and discussing preferences for final arrangements. These steps empower patients and reduce stress for families. Some choose to write letters, record videos, or share personal stories as part of legacy-building, leaving behind something meaningful for their loved ones.

Managing a Complex and Rare Metastasis with Comprehensive Care

Integrating Medical and Supportive Therapies

Colon cancer that metastasizes to the stomach wall is a rare and serious condition that demands expert, multidisciplinary care. While prognosis may be limited, outcomes have improved thanks to personalized treatments, advanced imaging, and better symptom control. A combination of systemic therapy, targeted care, nutritional and emotional support, and when appropriate, palliative or hospice services ensures that patients receive the most compassionate and comprehensive care possible.

Patients and families should remain hopeful but realistic, focused on quality of life, informed decision-making, and maintaining dignity throughout treatment. No two cases are alike—and care should always reflect the values, goals, and humanity of the person at the center of it all.

FAQ: Colon Cancer Metastasized to the Stomach Wall

What does it mean if colon cancer spreads to the stomach wall?

It means that cancer cells from the colon have traveled to the layers of the stomach, forming secondary tumors that complicate digestion and often signal advanced disease.

Is stomach wall metastasis common in colon cancer?

No, it is rare. Colon cancer more commonly spreads to the liver, lungs, and peritoneum. Stomach wall involvement occurs in a small percentage of advanced cases.

How is this different from primary stomach cancer?

Primary stomach cancer starts in the stomach lining, while metastatic colon cancer spreads from the colon and typically has distinct histological markers that help differentiate it.

What symptoms might appear in such cases?

Patients may experience nausea, early fullness, vomiting, abdominal pain, unintended weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding.

Can chemotherapy treat colon cancer in the stomach wall?

Yes. Standard regimens like FOLFOX or FOLFIRI are used, often with targeted therapies depending on genetic testing results.

Is surgery ever used for stomach wall metastasis?

Surgery is reserved for select cases where the metastasis is causing obstruction or bleeding, or when it is isolated and resectable.

How is the condition diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves endoscopy, imaging (CT, PET), biopsy, and immunohistochemical testing to confirm the cancer’s origin.

What are the treatment options besides chemo and surgery?

Immunotherapy, targeted therapy, palliative radiation, clinical trials, and supportive care are all part of the therapeutic arsenal.

Does this kind of spread affect prognosis?

Yes, stomach wall metastasis typically indicates stage IV disease and is associated with a more guarded prognosis.

Can the cancer return after treatment?

Yes, recurrence is common in metastatic disease. Regular monitoring is essential to detect and address progression early.

Are clinical trials a good option for these patients?

They may be, especially for those who have exhausted standard treatments or have unique tumor mutations.

What role does nutrition play in treatment?

Proper nutrition supports treatment tolerance, immune function, and overall quality of life, and should be managed proactively.

Is palliative care the same as hospice?

No. Palliative care focuses on symptom relief at any stage, while hospice is reserved for end-of-life care when curative treatments are no longer pursued.

How do patients emotionally cope with this diagnosis?

Many experience fear or sadness. Support groups, counseling, and honest conversations with care teams help patients navigate the emotional burden.

Does genetics play a role in this metastasis?

Yes, mutations such as KRAS, BRAF, and MSI-H status can affect how aggressively the cancer behaves and how it spreads.