Understanding Bladder Cancer in Cats: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Care

- What Is Bladder Cancer in Cats?

- Recognizing the Early Signs and Symptoms

- Causes and Risk Factors Behind Feline Bladder Cancer

- How Veterinarians Diagnose Bladder Cancer in Cats

- Treatment Options for Feline Bladder Cancer

- Prognosis and Survival Time for Affected Cats

- Differences Between Bladder Cancer and Other Feline Urinary Disorders

- Comparison of Urinary Disorders in Cats

- Managing Urinary Blockages and Emergencies

- Monitoring Progression and Adjusting Care Plans

- Palliative and End-of-Life Care Considerations

- Supporting Cat Owners Through the Diagnosis

- Differences Between Bladder Cancer in Cats and Dogs

- Preventive Insights: Can Bladder Cancer Be Avoided?

- Research and Future Outlook in Feline Bladder Cancer

- Compassionate Management of a Complex Disease

- FAQ

What Is Bladder Cancer in Cats?

Bladder cancer in cats is a rare but serious condition that typically originates in the urinary bladder’s lining or muscular wall. The most common type of tumor is called transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), an aggressive cancer that can invade surrounding tissues and metastasize to distant organs if left untreated.

While it accounts for a small percentage of all feline cancers, bladder cancer often presents diagnostic challenges because its symptoms overlap with more common urinary tract conditions, such as infections or bladder stones. This disease tends to occur more frequently in middle-aged to older cats, with no strong breed or sex predilection, though some suggest a slightly higher incidence in females.

Due to its low prevalence and vague early signs, bladder cancer is often diagnosed at a more advanced stage. Early detection and appropriate intervention are critical for improving quality of life and extending survival time in affected cats.

Recognizing the Early Signs and Symptoms

Identifying the signs of bladder cancer early is essential, but unfortunately, most symptoms are nonspecific and resemble other urinary tract issues. The most common clinical signs include:

- Straining to urinate (stranguria)

- Blood in the urine (hematuria)

- Frequent urination (pollakiuria)

- Urinating in inappropriate places

- Vocalization or discomfort during urination

- Lethargy or decreased appetite in later stages

As the tumor grows, it may obstruct the urethra or even lead to urinary retention, which can become a life-threatening emergency. Some cats might display behavioral changes, become withdrawn, or exhibit signs of pain when their abdomen is touched.

Because these symptoms mimic those of cystitis or urinary tract infections, bladder cancer may be overlooked initially. Persistent symptoms despite antibiotic treatment should prompt further diagnostic work-up, especially in older cats.

Causes and Risk Factors Behind Feline Bladder Cancer

The exact causes of bladder cancer in cats remain poorly understood. Like many other cancers in both animals and humans, it likely results from a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental exposure. Potential contributing factors include:

- Chronic inflammation of the bladder lining (interstitial cystitis)

- Exposure to certain herbicides or pesticides in the household

- Obesity or metabolic stress, which may alter normal cell regulation

- Secondhand smoke or chemical inhalants

- Advanced age, as cancer risk generally increases with time

Though no direct genetic mutation has been firmly linked to feline bladder cancer, the role of cellular mutations in driving abnormal tissue growth is consistent with mechanisms seen in human cancers, including bile duct cancer where specific mutations influence tumor progression.

Understanding risk factors may help veterinarians assess which patients warrant closer monitoring, especially when chronic urinary issues persist without a clear cause.

How Veterinarians Diagnose Bladder Cancer in Cats

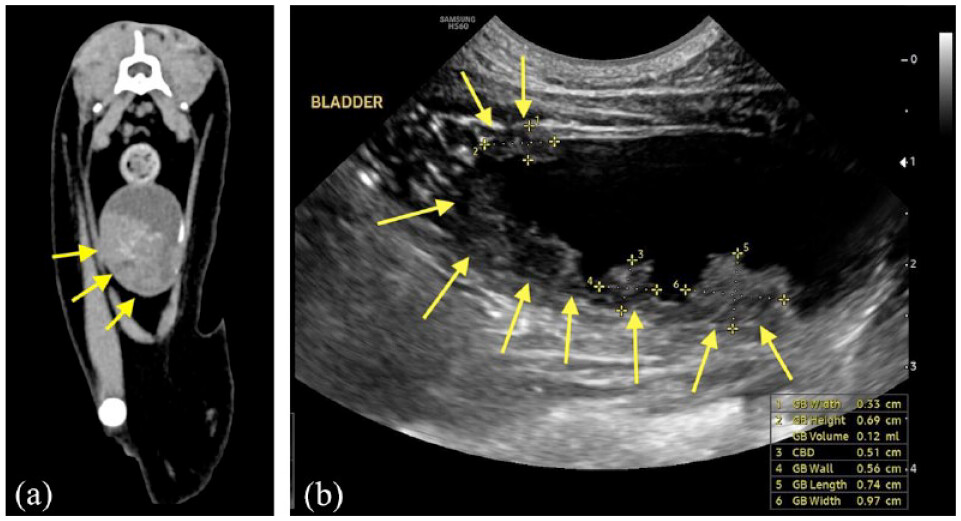

The diagnostic process for bladder cancer begins with a thorough clinical examination and a detailed history of urinary symptoms. From there, vets often pursue a combination of laboratory and imaging tools, including:

- Urinalysis, to check for blood, abnormal cells, or infection

- Urine culture, to rule out bacterial causes

- Cytology, where urine samples are examined under a microscope for cancerous cells

- Abdominal ultrasound, which can visualize mass formation in the bladder wall

- X-rays or contrast radiography, used to detect tumors and rule out bladder stones

- Biopsy or fine-needle aspirate, providing tissue for a definitive diagnosis

One of the challenges in feline bladder cancer is that urine cytology is often inconclusive, especially in low-grade tumors. Therefore, imaging and tissue sampling are typically required. It is crucial to differentiate bladder cancer from benign conditions to avoid unnecessary or ineffective treatments.

Treatment Options for Feline Bladder Cancer

The treatment of bladder cancer in cats depends on the tumor’s size, location, degree of invasiveness, and whether it has spread (metastasized). Because most feline bladder tumors are diagnosed late and are locally invasive, surgical removal is often not a viable option. In some cases, if the tumor is confined to a small, accessible area, partial cystectomy (removal of part of the bladder) may be attempted, but this is rare.

The primary treatment modality is medical management, particularly with:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like piroxicam or meloxicam, which may help slow tumor growth and reduce inflammation

- Chemotherapy, such as mitoxantrone or doxorubicin, administered by a veterinary oncologist to target systemic disease

- Targeted therapy or tyrosine kinase inhibitors, still under investigation but potentially promising

Radiation therapy is not commonly used in cats due to anatomical limitations and higher risk of adverse effects on nearby organs like the intestines. However, palliative care is essential and includes pain management, hydration, and nutritional support.

Veterinarians must also address the emotional side of care, preparing owners for long-term monitoring similar to how humans track biochemical relapse in prostate cancer via PSA levels. Biochemical relapse prostate cancer – as an analogue of systemic monitoring of relapse.

Prognosis and Survival Time for Affected Cats

Prognosis for cats diagnosed with bladder cancer is generally guarded to poor, particularly because of the tumor’s aggressive nature and late-stage detection. On average, cats treated symptomatically or with NSAIDs may survive 3 to 6 months, while those receiving chemotherapy and targeted care may live closer to 6 to 12 months—occasionally longer with early diagnosis and excellent response.

Several factors influence survival:

- Tumor size and location

- Presence or absence of metastasis

- Response to anti-cancer drugs

- Degree of urinary obstruction

Quality of life should be prioritized, and treatment goals must be individualized. In some cases, owners may choose palliative care only, focusing on comfort and supportive measures. Regular rechecks and imaging help assess tumor progression and ensure the chosen management remains effective and humane.

Differences Between Bladder Cancer and Other Feline Urinary Disorders

One of the greatest diagnostic challenges lies in distinguishing bladder cancer from other, more common urinary tract conditions in cats. Chronic cystitis, bladder infections, idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease (FLUTD), and even urinary crystals or stones can present with nearly identical symptoms.

Key distinguishing factors include:

- Persistence of symptoms despite antibiotic or anti-inflammatory therapy

- Lack of bacterial growth in urine cultures

- Recurrent hematuria without obvious cause

- Visible bladder wall thickening or mass on ultrasound

Because of these similarities, bladder cancer is often misdiagnosed until advanced stages. This reinforces the importance of thorough diagnostic imaging and cytology in cats with ongoing urinary issues.

Comparison of Urinary Disorders in Cats

| Condition | Common Signs | Key Diagnostic Clues | Treatment Options |

| Bladder Cancer | Straining, blood, frequency | Mass on imaging, malignant cells in urine | NSAIDs, chemotherapy, palliative care |

| Idiopathic Cystitis | Painful urination, vocalizing | No infection, history of stress | Diet change, stress management |

| Bacterial Urinary Infection | Frequent urination, odor, blood | Positive culture, leukocytes in urine | Antibiotics, hydration |

| Bladder Stones (Urolithiasis) | Intermittent obstruction, hematuria | Radiopaque stones, sediment in urine | Diet dissolution, surgical removal |

| FLUTD (mixed causes) | Variable symptoms | Diagnosis of exclusion | Multifactorial approach |

This table helps clarify how bladder cancer differs from more treatable urinary disorders, emphasizing the need for early and comprehensive diagnostic work.

Managing Urinary Blockages and Emergencies

A critical complication of bladder cancer in cats is urethral obstruction, which occurs when the tumor compresses or blocks the urinary outflow tract. This situation constitutes a medical emergency, as it can lead to bladder rupture, kidney failure, and death within 24–48 hours if untreated.

Signs of obstruction include:

- Repeated straining with no urine output

- Distended, painful abdomen

- Lethargy or collapse

- Vomiting

- Crying or hiding behavior

Initial emergency management involves catheterization, pain control, IV fluids, and sometimes sedation or anesthesia. In severe or recurrent cases, perineal urethrostomy (PU surgery) may be considered to create a wider urinary passage, especially in male cats. While PU does not treat the tumor, it can restore quality of life in cases where obstruction is the main concern.

Owners must be educated to watch for signs of difficulty urinating and to seek immediate care. Emergency readiness is especially crucial for cats in the later stages of bladder cancer, when obstructions are more likely to occur suddenly.

Monitoring Progression and Adjusting Care Plans

Bladder cancer in cats requires ongoing monitoring to track progression, response to therapy, and emerging complications. The veterinarian will schedule regular follow-ups, which may include:

- Physical exams every 4–8 weeks

- Repeat ultrasounds to assess tumor size and spread

- Bloodwork to monitor organ function and detect treatment-related side effects

- Urinalysis and possibly urine cytology for recurrence or infection

Adjustments to care plans are made based on the cat’s evolving condition. If NSAIDs are no longer effective, a chemotherapy protocol may be initiated. Conversely, if aggressive treatment becomes too burdensome, the focus may shift to palliative care only.

This model of adaptive, individualized treatment parallels management in certain non-cutaneous cancers with complex, chronic behavior—such as basal cell carcinomas tracked via ICD coding in human dermatologic oncology. Basal cell skin cancer icd 10 – an example of long-term observation with a change in tactics.

Open communication between the veterinary team and the pet owner is key to making these adjustments humane, timely, and in the best interest of the cat.

Palliative and End-of-Life Care Considerations

In cases where bladder cancer becomes unresponsive to treatment, or the cat’s quality of life declines significantly, palliative care becomes the central focus. This involves:

- Pain control using medications like buprenorphine or gabapentin

- Antispasmodic drugs to ease straining

- Anti-nausea medication

- Appetite stimulants or assisted feeding

- Home modifications for comfort (easy access to litter boxes, warm bedding, hydration support)

Ultimately, when suffering outweighs benefits, the decision for humane euthanasia may be considered. Veterinarians will guide this process compassionately, ensuring that owners understand the signs of end-stage disease such as complete urinary blockage, persistent inappetence, or severe pain.

The goal is to preserve dignity and comfort, ensuring that the final phase of the cat’s life is as peaceful as possible. Emotional support for grieving owners is also a vital part of veterinary oncology.

Supporting Cat Owners Through the Diagnosis

A diagnosis of cancer in a beloved pet is overwhelming for many families. Veterinarians must offer not only clinical expertise but also emotional guidance and clear communication. Owners often struggle with guilt, confusion, or a sense of helplessness.

Supportive care for owners includes:

- Providing written resources and prognosis details

- Offering second opinions or referral to oncology specialists

- Discussing finances and realistic expectations

- Ensuring 24/7 emergency contact information is available

- Referring to pet loss counseling if needed

Bladder cancer requires a partnership between the veterinary team and the pet family. With the right support system in place, even a challenging diagnosis can become an experience of love, advocacy, and deep care.

Differences Between Bladder Cancer in Cats and Dogs

Although bladder cancer affects both cats and dogs, there are key differences in frequency, progression, and response to treatment. Transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) is far more common in dogs, particularly certain breeds like Scottish Terriers, Beagles, and Shelties. In contrast, feline bladder cancer remains a rare diagnosis with more limited breed correlation.

Canine patients are often diagnosed earlier due to more routine urinalysis and behavioral observation. Additionally, dogs have more well-documented responses to NSAIDs and chemotherapy protocols, supported by broader clinical trials. Cats, on the other hand, are more sensitive to medications and require species-specific dosing and monitoring.

Furthermore, dogs tolerate surgical interventions and radiation therapy better than cats, which limits aggressive treatment options in feline oncology. Understanding these distinctions helps veterinarians set realistic expectations and refine diagnostic and care strategies based on species-specific factors.

Preventive Insights: Can Bladder Cancer Be Avoided?

At this time, there is no guaranteed way to prevent bladder cancer in cats, largely due to its unclear etiology. However, some proactive steps may help reduce general cancer risk and support urinary tract health:

- Keep cats indoors or in protected environments to reduce exposure to environmental toxins (e.g., lawn chemicals, automotive fluids, herbicides)

- Provide high-moisture diets to maintain optimal urinary dilution

- Address chronic urinary inflammation or infections promptly

- Schedule regular veterinary check-ups, especially for senior cats

Although not directly comparable, the broader strategy of preventing long-term inflammation and tracking subtle cellular abnormalities has applications in many oncological settings, including liver and bile duct cancers. Bile duct cancer icd 10 – as an analogue of systemic oncoprophylaxis.

Education, vigilance, and a proactive approach to urinary health remain the most practical steps owners can take toward early detection and intervention.

Research and Future Outlook in Feline Bladder Cancer

Veterinary oncology is an evolving field, and bladder cancer in cats—while uncommon—is gaining increasing attention. Current research efforts are focused on:

- Identifying molecular markers for earlier, more accurate diagnosis

- Exploring new NSAIDs and targeted therapies with fewer side effects

- Investigating minimally invasive diagnostic tools like liquid biopsies

- Establishing multicenter clinical trials to improve evidence-based protocols

Cats are underrepresented in oncology trials compared to dogs, partly due to their physiology and challenges in recruiting large enough study populations. Nonetheless, dedicated feline cancer research is expanding, with more institutions prioritizing species-specific oncology advancements.

Improved understanding of genetic mutations, immune responses, and pharmacokinetics in cats will likely lead to better diagnostics and more precise, tolerable therapies in the years ahead.

Compassionate Management of a Complex Disease

Bladder cancer in cats is a serious, often late-diagnosed condition that requires a multifaceted approach. From recognizing vague symptoms to navigating complex treatments, veterinary teams must combine clinical skill with empathy.

Key takeaways:

- Early signs can be subtle and easily mistaken for routine urinary issues

- Diagnostic imaging and tissue analysis are crucial for accuracy

- Treatment focuses on NSAIDs, symptom relief, and select chemotherapy

- Quality of life must guide all decisions, especially in advanced stages

With early recognition, compassionate care, and tailored management, many cats can experience meaningful months of comfort and connection—even with this challenging diagnosis.

FAQ

What is the most common type of bladder cancer in cats?

The most common form of bladder cancer in cats is transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). This cancer arises from the lining of the bladder and is known for being locally invasive. It can penetrate the bladder wall and may eventually spread to surrounding organs or lymph nodes if not diagnosed early.

Are certain cat breeds more prone to bladder cancer?

Unlike in dogs, where breed predisposition is more evident, bladder cancer in cats doesn’t strongly correlate with specific breeds. However, it tends to occur in older cats, typically over the age of 10. There’s no well-established sex or breed predilection.

How is feline bladder cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a combination of urinalysis, urine cytology, abdominal ultrasound, and sometimes biopsy. Imaging can help identify masses, while cytological analysis may detect malignant cells. A definitive diagnosis often requires a sample of the bladder wall or mass.

Can bladder cancer be mistaken for a urinary tract infection?

Yes, very often. Early symptoms like blood in the urine, straining to urinate, and frequent urination overlap with urinary infections. If symptoms persist despite antibiotics, vets should explore more serious conditions like cancer.

What is the prognosis for cats with bladder cancer?

The prognosis is generally guarded to poor, especially when diagnosed late. With palliative treatment, survival times average 3–6 months. Some cats may live up to a year with responsive tumors and consistent veterinary care.

Is surgery a viable treatment for bladder cancer in cats?

In rare cases, if the tumor is small and confined to a region that can be safely accessed, partial bladder surgery may be attempted. However, most tumors are not surgically resectable due to their location or invasiveness at diagnosis.

What medications are used in treating feline bladder cancer?

The most common medications include NSAIDs like piroxicam or meloxicam, which may slow tumor growth and reduce discomfort. Chemotherapy agents like mitoxantrone or doxorubicin may also be used under oncology supervision.

Can radiation therapy be used in cats?

Radiation is rarely used in feline bladder cancer due to the high risk of damaging nearby organs. Cats are also more sensitive to radiation compared to dogs, making this option less common.

What can I do at home to support my cat?

Owners can focus on hydration, pain management, easy litter access, and nutritional support. Ensuring a stress-free environment and observing urination habits daily are important. Follow-up with your vet regularly to adjust care as needed.

How often should follow-up exams be done?

Typically, follow-ups occur every 4–8 weeks, depending on disease progression and the chosen treatment plan. These may include physical exams, urinalysis, and imaging to monitor tumor size and detect complications.

Is euthanasia often necessary?

In advanced stages, when the cat experiences significant pain, obstruction, or no longer responds to treatment, humane euthanasia may be considered. This is always a difficult decision and should be discussed openly with your veterinarian.

Does bladder cancer spread to other parts of the body?

Yes, in some cases, TCC can metastasize to the lungs, lymph nodes, or kidneys. However, in many cats, the primary concern is local invasion and urethral obstruction rather than distant spread.

Can a cat live comfortably with bladder cancer?

With appropriate palliative care and symptom control, many cats can enjoy good quality of life for several months. Pain relief, frequent check-ups, and adjusting care strategies can help ensure their comfort.

What are the emergency signs I should look out for?

Signs of urinary obstruction, such as straining without output, vomiting, crying, or lethargy, are emergencies. Immediate veterinary intervention is required to prevent kidney failure or bladder rupture.

Should I get a second opinion from a specialist?

Absolutely. Veterinary oncologists have specialized training in cancer care and can offer advanced treatment options, prognosis insights, and customized care plans. A second opinion can be especially helpful in complex or late-stage cases.