Types of Breast Cancer: From Papillary to Inflammatory

Types of Breast Cancer: From Papillary to Inflammatory

- Foreword

- Part 1: Why the Type of Breast Cancer Matters

- Part 2: How Breast Cancer Is Classified

- Part 3: Common Histological Types of Breast Cancer

- Part 4: Papillary Breast Cancer: What Makes It Different

- Part 5: Inflammatory Breast Cancer: Understanding the Aggressive Outlier

- Part 6: Rare and Aggressive Types: Metaplastic Carcinoma

- Part 7: Hormone Receptors, HER2 Status, and How They Shape Treatment

- Part 8: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Special Challenge

- Part 9: How Doctors Diagnose Breast Cancer Type

- Part 10: Treatment Planning Based on Breast Cancer Type

- Part 11: Living with Different Types of Breast Cancer

- Part 12: FAQs About Breast Cancer Types

Foreword

If you’ve recently been told you have breast cancer — or if you’re helping someone who has — the sheer number of different types and labels can feel overwhelming. Ductal, lobular, papillary, inflammatory, triple-negative — the names come fast, often before there’s even time to process what they all mean.

Understanding the type of breast cancer isn’t about memorizing complicated medical terms. It’s about knowing what doctors are looking at when they recommend treatments, what to expect in the months ahead, and what questions you might want to ask. Some types behave slowly and predictably. Others move faster and need a different kind of plan. Each one carries its own challenges — but none of them take away the strength, dignity, or possibilities that remain.

This article is here to walk you through it carefully and respectfully. We’ll explain how doctors classify breast cancer, what the different types mean, how they affect treatment decisions, and why understanding these distinctions can help you feel a little more grounded at a time when everything feels uncertain.

Let’s start from the beginning — with why doctors focus so much on the “type” of breast cancer in the first place.

Part 1: Why the Type of Breast Cancer Matters

When a doctor talks about the “type” of breast cancer, they’re not just using medical jargon for the sake of it. The type tells them what the cancer cells look like, how they behave, how likely they are to spread, and which treatments are likely to work best. It’s one of the first keys to building a treatment plan that fits the real situation, not just the statistics.

Breast cancer is not one single disease. Some types grow slowly. Others move quickly. Some respond well to hormone-blocking treatments. Others need different, more aggressive approaches. Understanding the type helps doctors — and patients — make decisions that are based on what the cancer is actually doing, not just on its size or location.

You might wonder why the type matters so much if all breast cancers can potentially spread or recur. The answer is that the path a cancer takes — how fast it moves, where it tends to go, how it responds to drugs — is strongly tied to its biological behavior, and that behavior depends heavily on type. Two people can have tumors the same size and stage, but their cancers may behave very differently if the types are different.

In practical terms, knowing the type shapes almost every decision. Should surgery come first, or chemotherapy? Is hormone therapy an option? Would a targeted drug be better than standard chemotherapy? Is there a high risk of recurrence that needs aggressive treatment now, or a low risk where smaller interventions could be enough? All of these questions start with the basic facts revealed by type.

For patients, knowing the type of breast cancer also helps make the road ahead less mysterious. It gives context when doctors talk about treatment options, expected responses, possible side effects, and what kind of monitoring will be needed over time. It’s not about predicting the future with perfect accuracy — no test or label can do that — but it is about making decisions with open eyes and a real understanding of the disease.

In the next section, we’ll take a closer look at how doctors classify breast cancer, because “type” turns out to have more than one meaning in the medical world.

Part 2: How Breast Cancer Is Classified

When doctors talk about the “type” of breast cancer, they’re often referring to more than one thing. Part of it is about where the cancer started and how the cells look under a microscope. But there’s also a second layer — what drives the cancer’s growth at a molecular level. Both levels are important, and they come together to shape the overall diagnosis and treatment plan.

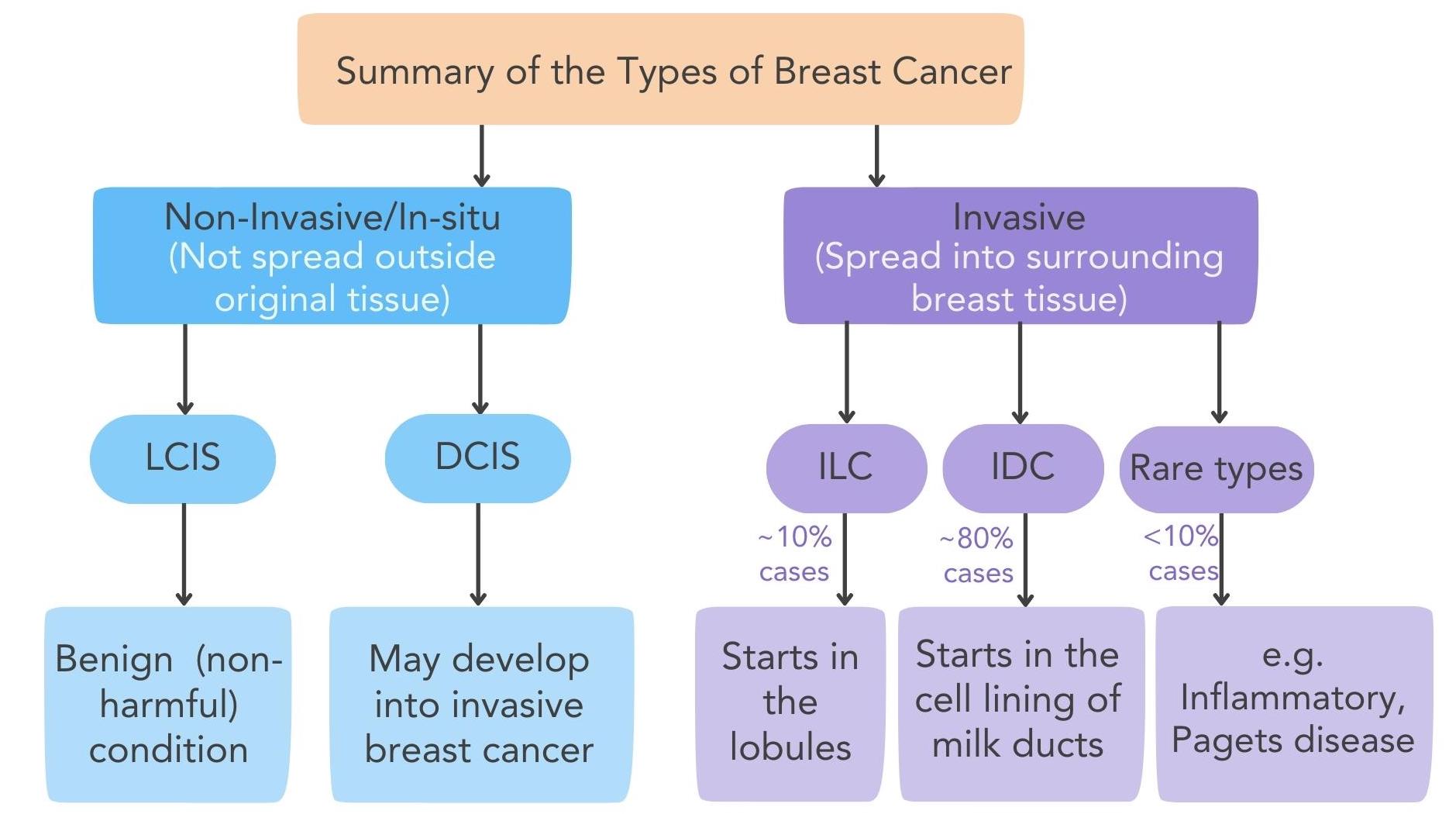

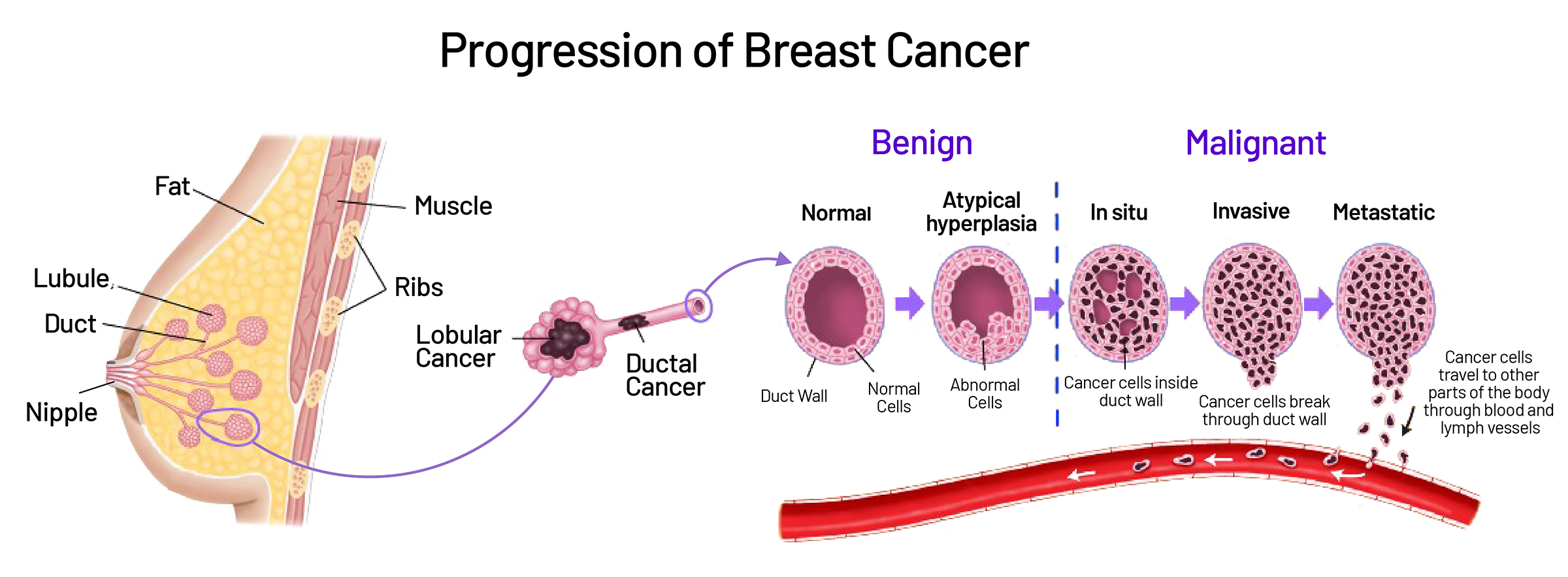

First, there’s histological type. This means the pathologist looks at the cancer cells under a microscope and identifies where the tumor began — most often in the milk ducts or the milk-producing lobules. The structure, pattern, and appearance of the cells tell a lot about how the cancer behaves. A ductal carcinoma may spread differently than a lobular carcinoma, even if they are the same size.

Next, there’s molecular subtype. This has to do with proteins and receptors on the surface of the cancer cells. Some cancers have receptors for estrogen or progesterone — hormones that help them grow. Some have too much of a protein called HER2, which makes them more aggressive but also vulnerable to specific targeted treatments. Others, called triple-negative cancers, don’t have any of these markers and need a different approach altogether.

You’ll sometimes hear about grade and stage too, but these are different. Grade describes how abnormal the cancer cells look and how quickly they’re likely to grow. Stage describes how far the cancer has spread. Type focuses on what kind of cancer it is at its core, not how big it is or how far it has traveled.

It’s normal to feel overwhelmed hearing so many labels at once — ductal, HER2-positive, Grade 2, Stage II — but each piece gives doctors critical information. They aren’t just piling on terms; they’re building a complete picture that helps guide choices. Understanding how type fits into that bigger puzzle can make the flood of information a little easier to handle.

Now that we’ve laid out the basics, let’s get more specific. The next part will walk you through the most common histological types of breast cancer — what they are, how they behave, and why those differences matter.

Part 3: Common Histological Types of Breast Cancer

Breast cancer can take many forms, and each type behaves a little differently. Some grow slowly and stay contained for a long time. Others move faster and require more aggressive treatment. Knowing the basic histological types — the types defined by what the cancer cells look like under the microscope — helps doctors predict how the disease might act and what treatments are likely to work best.

Let’s walk through the major types, one by one:

- Ductal Carcinoma In Situ (DCIS)

DCIS is sometimes called “stage 0” breast cancer. The cancer cells are inside the milk ducts but haven’t broken through into surrounding breast tissue. Even though DCIS isn’t invasive, it’s important to treat it, because it can develop into invasive cancer over time if left alone. Treatments usually involve surgery, sometimes radiation, and, depending on hormone receptor status, medications to lower recurrence risk.

- Invasive Ductal Carcinoma (IDC)

IDC is the most common type of invasive breast cancer. It starts in the milk ducts but has broken through into surrounding breast tissue. IDC can grow outward into the breast and, if not treated, can spread to lymph nodes or distant organs. Because it’s so common, most clinical trials and treatments are built around it. IDC can be hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive, or triple-negative, depending on the tumor’s biology.

- Invasive Lobular Carcinoma (ILC)

ILC starts in the milk-producing lobules and invades surrounding tissue. It behaves differently from IDC in a few key ways. It often grows in single-file lines instead of forming lumps, which can make it harder to spot on mammograms. ILC can also be more likely to show up in unusual places like the gastrointestinal tract or ovaries if it spreads. Most ILC tumors are hormone receptor-positive, which opens options for hormone therapy.

- Medullary Carcinoma

This is a rare type of breast cancer that tends to behave less aggressively than its appearance might suggest. Under the microscope, medullary tumors can look alarming — with lots of immune cells mixed in — but in real life, many respond well to treatment. Some medullary cancers are triple-negative, but they don’t always act as aggressively as typical triple-negative tumors.

- Mucinous (Colloid) Carcinoma

Mucinous breast cancer produces large amounts of mucus. When pathologists examine it, the tumor looks gelatinous and less dense than most cancers. This type usually grows slowly and has a better prognosis than many others. Mucinous cancers are often found in older women and are frequently hormone receptor-positive, making them responsive to hormone-based treatments.

- Papillary Carcinoma

Papillary carcinoma — one of our main focuses here — has a distinct finger-like growth pattern under the microscope. It usually affects older women and tends to grow slowly. Most papillary cancers are contained within a cyst or capsule and have a relatively good prognosis, although invasive forms can behave more like other invasive breast cancers. We’ll go deeper into papillary carcinoma shortly.

- Tubular Carcinoma

Tubular breast cancer is named for the tube-shaped structures the cancer cells form. It’s a rare type but generally carries an excellent prognosis. Tumors are usually small and slow-growing, often picked up early through mammograms. They are typically hormone receptor-positive and respond well to surgery and hormone therapy without needing aggressive chemotherapy.

- Metaplastic Carcinoma

Metaplastic carcinoma is rare and aggressive. Unlike most breast cancers that resemble ductal or lobular tissue, metaplastic tumors can look like bone, cartilage, or even muscle under the microscope. These tumors are often triple-negative and resist standard treatments. Because they behave differently, doctors sometimes recommend more experimental or clinical trial options.

- Inflammatory Breast Cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is not a separate type under the microscope but a distinct clinical presentation. Cancer cells block lymphatic vessels in the skin, causing redness, swelling, and warmth that mimic infection. IBC moves fast and needs aggressive, multi-step treatment — typically starting with chemotherapy before surgery or radiation. We’ll cover it in full detail later because of its unique challenges.

Breast cancer’s diversity is one of the reasons treatments vary so much from patient to patient. No two cancers — and no two people — follow exactly the same path. Understanding the basic histological types gives a foundation for everything that comes next.

Coming up, we’ll dig deeper into papillary breast cancer — what sets it apart, who it affects most, and how it’s usually treated.

Part 4: Papillary Breast Cancer: What Makes It Different

Papillary breast cancer stands out because of how it looks under the microscope and how it behaves in real life. It’s relatively rare, making up only about 1–2% of all breast cancers. Yet when it appears, it often behaves less aggressively than many other types — especially when caught early.

This type of cancer gets its name from the way the cells grow in slender, finger-like projections called papillae. These structures are often surrounded by a cystic or fluid-filled space, giving the tumor a very distinct appearance compared to more common breast cancers like ductal or lobular carcinoma.

Most cases of papillary breast cancer happen in older women, typically over the age of 60. Doctors aren’t entirely sure why age plays such a strong role, but hormonal changes after menopause may be part of the reason. It’s less common to see papillary carcinoma in younger women, although it can happen.

Papillary breast cancer can appear in two main forms:

- Encapsulated (Non-invasive) Papillary Carcinoma

In this form, the tumor is surrounded by a thick fibrous wall and has not yet invaded the surrounding breast tissue. It acts almost like a precancerous lesion and is sometimes treated similarly to ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Surgery is usually very effective, and many patients do not need chemotherapy if margins are clean and hormone receptors are positive.

- Invasive Papillary Carcinoma

In some cases, cancer cells break out of the cyst or capsule and invade surrounding breast tissue. When this happens, papillary carcinoma behaves more like other invasive breast cancers. Treatment typically involves surgery plus either radiation, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination — depending on receptor status and other tumor characteristics.

One of the challenges with papillary breast cancer is that it can look benign on imaging. On a mammogram or ultrasound, these tumors often appear well-circumscribed and cystic, not jagged or irregular like more aggressive tumors. Because of this, doctors sometimes mistake papillary cancers for harmless cysts or benign papillomas at first. A biopsy is essential to make sure nothing is missed.

The prognosis for papillary breast cancer is generally very good, especially when the tumor is hormone receptor-positive and detected early. Five-year survival rates are high, particularly for non-invasive cases. Even when the cancer is invasive, it tends to grow more slowly and spread later than other invasive cancers of similar size.

Patients diagnosed with papillary breast cancer often ask whether it’s “better” to have this type compared to others. While no cancer is ever truly “good,” papillary carcinoma usually offers more treatment options and a more favorable outlook than more aggressive types. With careful surgical removal and, when needed, appropriate systemic therapy, outcomes are often excellent.

Now that we’ve looked at papillary carcinoma, it’s time to shift gears and focus on one of the most aggressive forms of breast cancer: inflammatory breast cancer, which behaves very differently from the slow-growing patterns we’ve seen so far.

Part 5: Inflammatory Breast Cancer: Understanding the Aggressive Outlier

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) doesn’t behave like most other breast cancers. It doesn’t usually form a lump you can feel. It doesn’t wait quietly to be found on a mammogram. Instead, it spreads quickly through the skin and lymph vessels of the breast, causing swelling, redness, and warmth that can appear almost overnight.

In many ways, IBC looks more like an infection than a tumor. That’s one of the reasons it can be missed at first. Patients and even some doctors may mistake the early signs for mastitis or cellulitis — common infections that cause similar skin changes. Antibiotics are often prescribed initially, but when the redness doesn’t improve, further testing reveals the real cause.

Inflammatory breast cancer happens when cancer cells block lymphatic channels in the skin. The fluid that normally drains through the lymph system gets trapped, causing swelling (edema) and redness (erythema). The skin may take on a dimpled appearance, often compared to the surface of an orange (peau d’orange). Sometimes the breast feels heavy, painful, or warm to the touch. In some cases, the nipple may flatten or turn inward.

You might wonder how common IBC is. The answer is: rare, but serious. Inflammatory breast cancer makes up only about 1–5% of all breast cancer cases. Despite its rarity, it accounts for a disproportionate number of breast cancer deaths because of how quickly it moves and how easily it can spread before being diagnosed.

Because of its aggressive nature, inflammatory breast cancer is always considered at least Stage III at diagnosis — and often Stage IV if distant metastases are found. That classification changes the treatment approach immediately. Doctors don’t usually start with surgery, as they might for other breast cancers. Instead, they begin with chemotherapy to shrink the cancer, followed by surgery and radiation.

Typical treatment steps for IBC include:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (before surgery) to shrink the cancer and clear some of the lymphatic blockage.

- Modified radical mastectomy, removing the entire breast and many lymph nodes.

- Radiation therapy to the chest wall and regional lymph nodes to catch microscopic cancer cells that might still be present.

- Targeted therapy (such as HER2-directed treatments) if the cancer expresses HER2.

- Hormone therapy if the cancer is hormone receptor-positive.

Even with aggressive treatment, inflammatory breast cancer remains challenging. Survival rates are lower than for more common breast cancers, but outcomes have improved in recent years. According to studies, the five-year survival rate for IBC ranges between 30% and 55%, depending on factors like stage at diagnosis, response to treatment, and tumor biology. HER2-positive IBC, once very grim, now responds better thanks to newer targeted therapies.

Facing inflammatory breast cancer can feel like stepping into a different world compared to more familiar types. The pace is faster, the treatments are heavier, and the need for coordinated care is greater. But even so, many patients achieve good responses, long remissions, and meaningful quality of life through careful management and evolving therapies.

Coming up, we’ll look at another rare but aggressive type of breast cancer: metaplastic carcinoma, and how it fits into the broader picture of difficult-to-treat cancers.

Part 6: Rare and Aggressive Types: Metaplastic Carcinoma

Among the rare types of breast cancer, metaplastic carcinoma stands out for how different — and how difficult — it can be. It doesn’t just look unusual under the microscope; it behaves differently from most other breast cancers, often requiring more aggressive and creative treatment approaches.

Metaplastic carcinoma is rare, making up less than 1% of all breast cancer cases. What makes it different is that the cancer cells don’t stick to the typical breast tissue patterns. Instead, they can transform into cells that look like bone, cartilage, muscle, or even connective tissue. Under the microscope, one part of the tumor might look like standard ductal cancer, while another part looks completely foreign — almost like a different kind of tumor altogether.

Because of these differences, metaplastic carcinoma tends to be more aggressive. It grows faster, resists many standard treatments, and is more likely to spread to other parts of the body. Most metaplastic tumors are triple-negative — meaning they don’t have estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, or HER2 overexpression. Without these targets, hormone therapy and HER2-targeted treatments don’t work, leaving chemotherapy as the mainstay.

You might wonder if the unusual structure of metaplastic carcinoma offers any weaknesses doctors can exploit. Right now, unfortunately, the answer is no — at least not consistently. Research is ongoing to find therapies that better target these tumors’ unique biology, but as of today, treatment usually involves:

- Surgery to remove the tumor as completely as possible. Because metaplastic tumors often grow quickly, wide surgical margins are important to reduce the risk of local recurrence.

- Chemotherapy, although responses are often less robust than with typical triple-negative breast cancers.

- Radiation therapy to help prevent local recurrence, especially when surgical margins are close or when tumors are large.

- Clinical trials, offering access to experimental treatments like immunotherapy, anti-angiogenesis agents, or novel chemotherapy combinations.

For patients diagnosed with metaplastic breast cancer, the road can feel lonely simply because the type is so rare. Standard treatment pathways don’t always apply cleanly, and prognosis discussions tend to rely on small case series rather than large studies. Survival rates vary, but many patients face higher risks of recurrence and lower overall survival compared to more common types of breast cancer.

Still, research is moving forward. Some early studies suggest that certain metaplastic tumors may respond better to immunotherapy than traditional chemotherapy, opening the door to new treatment strategies. While these advances are still in their early stages, they offer hope that future options may be better tailored to the unique challenges metaplastic carcinoma presents.

Next, we’ll step back and look at another layer that shapes treatment even more than histology: hormone receptors, HER2 status, and what they mean for therapy across all types of breast cancer.

Part 7: Hormone Receptors, HER2 Status, and How They Shape Treatment

When a doctor examines a breast cancer tumor, they don’t just look at where it started or how the cells are arranged. They also check for special proteins on the surface of the cancer cells — proteins that tell them what’s driving the cancer’s growth, and what treatments are likely to work. These proteins include hormone receptors and HER2.

First, there are hormone receptors — specifically, receptors for estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR). If a breast cancer is ER-positive, it means that estrogen helps fuel its growth. The same goes for PR-positive tumors with progesterone. These cancers can often be treated successfully with hormone-blocking therapies, like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, that deprive the cancer of the signals it needs to keep growing.

If you hear your doctor say that your tumor is “hormone receptor-positive,” it usually means you have more options for long-term control. Hormone therapy is often easier to tolerate than chemotherapy, and it can be given for years to help keep the cancer from coming back.

Then there’s HER2 status. HER2 is a protein that, when overproduced, can make cancer cells grow faster and more aggressively. HER2-positive breast cancers used to have a very poor outlook, but that changed dramatically with the development of targeted therapies like trastuzumab (Herceptin), pertuzumab, and newer antibody-drug conjugates. If a tumor is HER2-positive, doctors typically recommend adding these targeted treatments to chemotherapy for the best chance of success.

Finally, some breast cancers are triple-negative — meaning they lack estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and HER2 overexpression. These tumors don’t respond to hormone therapy or HER2-targeted drugs. Instead, chemotherapy remains the primary treatment, often combined with newer immunotherapies when certain markers like PD-L1 are present.

It’s important to understand that hormone receptors and HER2 status cut across all histological types. A ductal carcinoma can be hormone receptor-positive or triple-negative. A lobular carcinoma can be HER2-positive, although it’s less common. Even rarer types like metaplastic carcinoma can have varied receptor statuses — although triple-negativity is more common there.

This molecular information matters because it often has more impact on treatment decisions than the histological type alone. Two tumors that look very different under the microscope might be treated similarly if they share the same hormone receptor and HER2 profile. On the flip side, two tumors that look similar might need very different treatments if their molecular drivers are different.

Understanding these markers gives patients — and doctors — more tools to personalize treatment plans. It’s not just about where the cancer started. It’s about what keeps it alive, and how best to shut that down.

Now that we’ve laid the groundwork, let’s take a closer look at triple-negative breast cancer, one of the most challenging subtypes to treat.

Part 8: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Special Challenge

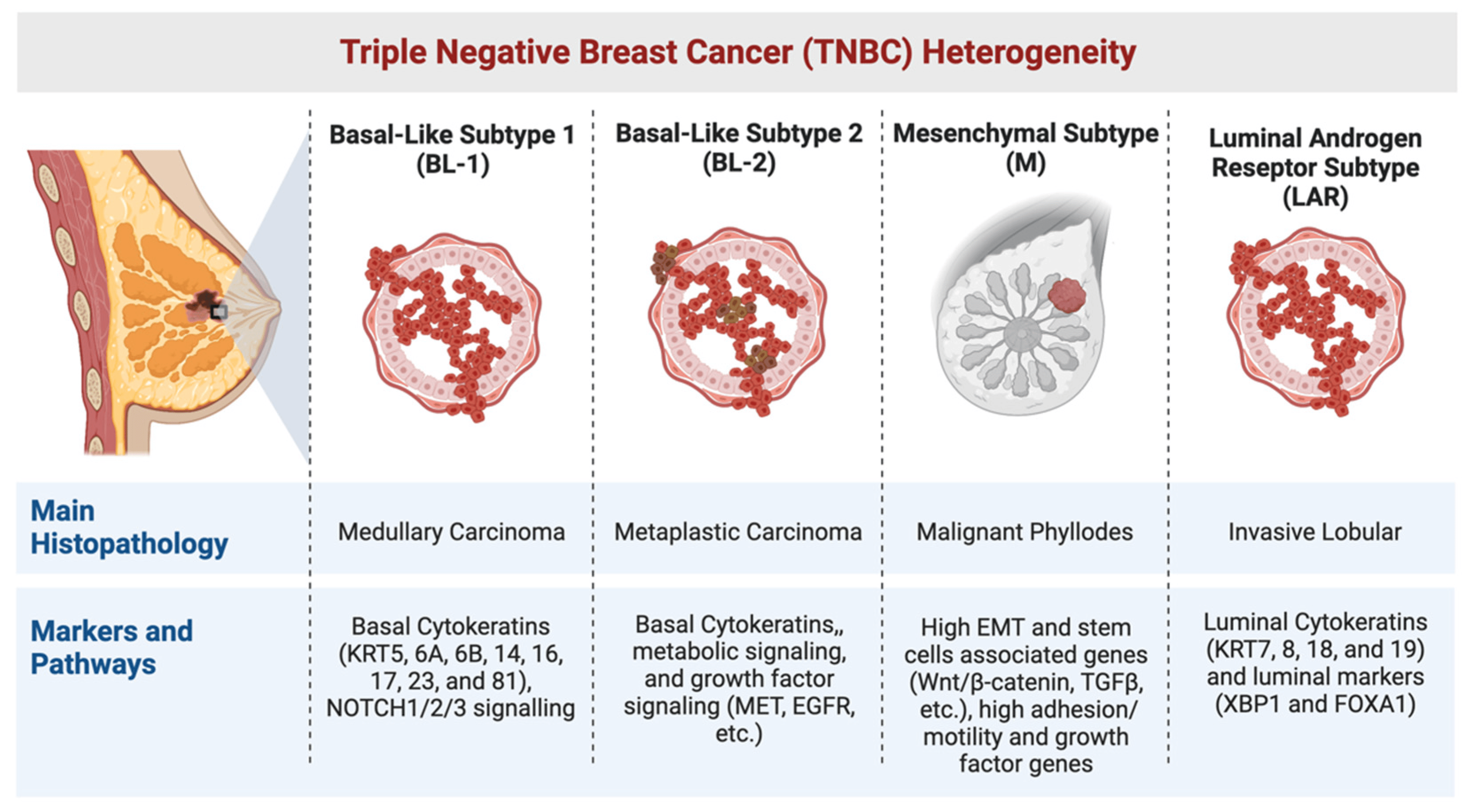

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) gets its name because the cancer cells test negative for estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and HER2 overexpression. Without these three common targets, treatment becomes more difficult. Doctors can’t use hormone-blocking drugs or HER2-targeted therapies. Instead, chemotherapy — often aggressive chemotherapy — remains the primary weapon.

TNBC accounts for about 10–15% of all breast cancer cases. It’s more common in younger women, particularly those under 50, and is seen more often in women of African descent and in patients with BRCA1 genetic mutations.

One of the hardest realities about triple-negative breast cancer is how fast it tends to move. Compared to hormone receptor-positive cancers, TNBC grows more quickly, spreads sooner to distant organs like the brain or lungs, and tends to recur earlier after treatment — often within the first three years if it recurs at all. After that high-risk window, though, the risk of recurrence drops sharply.

You might wonder why chemotherapy remains the mainstay despite its tough side effects. The answer is simple: for triple-negative breast cancer, chemotherapy still offers the best chance to shrink tumors, clear microscopic disease, and improve survival. Drugs like anthracyclines and taxanes form the backbone of treatment. In certain high-risk cases, platinum-based drugs like carboplatin are added because they seem particularly effective against TNBC.

In recent years, newer options have started to emerge. Some TNBC tumors express a marker called PD-L1, which allows doctors to add immunotherapy — drugs that help the immune system recognize and attack cancer cells. Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) combined with chemotherapy has shown benefit in patients whose tumors express PD-L1. More recently, antibody-drug conjugates like sacituzumab govitecan have offered new hope for patients with metastatic triple-negative disease.

Research is moving fast in this area. Clinical trials are constantly testing new combinations of chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted treatments aimed at finding better answers for TNBC patients. Many doctors encourage eligible patients to consider clinical trials early because breakthroughs often happen there first.

It’s important to remember that while triple-negative breast cancer carries real challenges, it is not untreatable — and it is not a death sentence. Many patients respond well to initial therapy, achieve complete remissions, and live long lives. The key lies in early detection, aggressive initial treatment, and careful follow-up afterward.

Next, we’ll look at how doctors confirm the type of breast cancer through biopsies and pathology — the essential steps that shape everything that follows.

Part 9: How Doctors Diagnose Breast Cancer Type

Every treatment plan starts with a clear diagnosis. Before doctors can recommend surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or anything else, they need to know exactly what kind of breast cancer they’re dealing with — both histologically and molecularly. That’s why biopsy and pathology are so critical.

When a suspicious lump, mass, or imaging abnormality is found, the next step is usually a biopsy. A biopsy means taking a small sample of tissue and sending it to a laboratory where a pathologist — a doctor trained to study cells under a microscope — examines it carefully.

There are different types of biopsies depending on the situation:

- Core needle biopsy

This is the most common method. Using a hollow needle, the doctor removes small cylinders of tissue from the tumor. Core biopsies provide enough material to analyze both the architecture of the tumor and the specific proteins expressed on the cancer cells.

- Excisional biopsy

If a core needle biopsy doesn’t give enough information, or if the lesion is hard to access, doctors may surgically remove the entire lump. This approach gives the pathologist a larger sample to work with but is usually reserved for cases where a needle biopsy isn’t feasible or inconclusive.

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA)

Sometimes used for sampling lymph nodes or cystic lesions, FNA involves removing cells with a thin needle. It’s less invasive but doesn’t give as much structural information as a core biopsy, so it’s not typically used for initial breast cancer diagnosis.

Once the tissue is collected, the pathologist examines it under the microscope. They determine the histological type — ductal, lobular, papillary, metaplastic, or others. They also assess the grade, meaning how abnormal the cells look and how fast they seem to be growing.

In addition, the tissue is tested for hormone receptors (ER and PR) and HER2 status. These tests are usually done using techniques called immunohistochemistry (IHC) and sometimes fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) if HER2 results are borderline. The results tell doctors whether hormone therapy, HER2-targeted therapy, or other strategies will be effective.

In more complex or unusual cases — such as very rare tumor types or ambiguous pathology — doctors may recommend sending the tissue for second opinion pathology review at a specialized cancer center. Even a small change in diagnosis can completely alter the treatment plan.

Patients sometimes ask if additional molecular testing is necessary beyond ER, PR, and HER2. The answer depends on the case. For early-stage, hormone receptor-positive cancers, genomic assays like Oncotype DX or MammaPrint may be used to predict recurrence risk and guide decisions about chemotherapy. In metastatic settings, broader genomic profiling may help identify rare mutations that could be targeted by clinical trial therapies.

Every decision that follows — from the choice of surgery to the sequence of therapies — is built on what the biopsy and pathology report show. Getting it right at the start gives the best chance of building a treatment plan that truly fits the cancer’s biology.

Ahead, we’ll walk through how treatment planning actually works once all this information is in hand — and why there’s no such thing as a “one-size-fits-all” approach to breast cancer.

Part 10: Treatment Planning Based on Breast Cancer Type

Once the biopsy results are in and the cancer’s type is known, doctors can start piecing together a treatment plan. This isn’t a simple, one-size-fits-all checklist. Instead, it’s a process that looks at the specific behavior of the cancer, the biology behind it, the stage at which it’s found, and the overall health and preferences of the patient.

For some cancers — like hormone receptor-positive, low-grade, small tumors — treatment might begin with surgery to remove the lump or breast tissue, followed by hormone therapy to reduce the risk of recurrence. For others — like inflammatory breast cancer or large triple-negative tumors — treatment usually starts with chemotherapy to shrink the cancer before surgery is even considered.

You might notice that two patients with “breast cancer” get completely different first steps. One starts with surgery; another with chemotherapy. One has hormone therapy afterward; another doesn’t. One gets radiation therapy; another skips it. That’s because the type of breast cancer, along with its stage, molecular profile, and behavior, shapes the order, intensity, and kinds of treatments used.

Here’s how the main treatments fit into the picture:

- Surgery

Surgery removes the primary tumor. Depending on the tumor’s size, location, and spread, this could mean a lumpectomy (removing the tumor and some surrounding tissue) or mastectomy (removing the entire breast). Lymph node evaluation is usually done at the same time to check for spread.

- Radiation therapy

Radiation is often used after lumpectomy to kill any microscopic cancer cells left behind. It’s also used after mastectomy if the tumor was large, involved lymph nodes, or had close surgical margins. In cases like inflammatory breast cancer, radiation is critical even after full mastectomy to lower recurrence risk.

- Chemotherapy

Chemo is used either before surgery (neoadjuvant) or after surgery (adjuvant) depending on the situation. It’s almost always part of treatment for triple-negative and HER2-positive cancers, and for hormone receptor-positive cancers when they are high-grade, large, or involve multiple lymph nodes.

- Hormone therapy

For cancers that express estrogen or progesterone receptors, hormone therapy (like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors) helps starve the cancer of hormones that fuel its growth. It’s typically prescribed for at least five years, sometimes longer.

- Targeted therapy

HER2-positive cancers benefit from targeted drugs like trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab. These therapies specifically attack HER2-overexpressing cells while sparing normal ones, dramatically improving outcomes for this group.

- Immunotherapy and experimental treatments

In some cases, especially metastatic triple-negative disease, immunotherapy or new targeted treatments may be added based on tumor markers or participation in clinical trials.

As science moves forward, personalized medicine becomes more central. Doctors no longer treat breast cancer based solely on where it started; they look at how it behaves at the molecular level. Some patients may have genetic tests like Oncotype DX to predict whether chemotherapy will help. Others may have genomic profiling to find rare targets for new drugs.

Treatment plans also evolve over time. If a cancer recurs, or if it spreads, the original plan may change based on how the tumor adapts and what new options become available.

Knowing the cancer’s type, receptor status, grade, and stage doesn’t just help doctors choose treatments. It gives patients a roadmap — a way to understand why certain steps are taken, why some are skipped, and how each piece fits into the bigger fight.

Up next, we’ll talk about what it’s really like to live with different types of breast cancer — the emotional, practical, and day-to-day realities that numbers and reports can’t fully capture.

Part 11: Living with Different Types of Breast Cancer

Getting a diagnosis of breast cancer isn’t just a medical event — it changes everyday life in ways that test patience, courage, and identity. The type of cancer matters medically, but it also shapes the personal journey each patient faces.

For some, living with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer means years of hormone therapy. That can bring its own challenges — hot flashes, joint aches, fatigue, and the quiet worry that any new ache or pain could signal a recurrence. Daily pills become part of life, checkups stretch on for years, and managing side effects becomes part of the long game of survivorship.

Patients with HER2-positive cancers often face intense initial treatments, with chemotherapy and targeted therapy running side-by-side. Infusion centers become familiar places. Over time, the urgency of treatment often gives way to a quieter but persistent vigilance, with regular scans and blood tests to make sure the cancer stays gone.

For those with triple-negative breast cancer, the path can feel more abrupt and uncertain. Chemotherapy tends to be aggressive. Follow-up involves watching closely for signs of recurrence in the first few years. There’s often a heavier psychological weight because triple-negative disease is harder to predict — both in its risk of returning and in how it behaves if it does.

When rarer types like inflammatory breast cancer or metaplastic carcinoma are involved, the journey can be even more isolating. Support groups and online forums often cater to more common types of breast cancer, leaving patients with rare diagnoses searching for people who understand their specific battles. The treatments may be harsher, the unknowns greater, and the language around “beating cancer” harder to navigate when survival statistics aren’t as rosy.

At the same time, many patients adapt in ways that surprise even themselves. They learn how to live with uncertainty, how to balance normal life with medical appointments, how to advocate for their own needs within a healthcare system that doesn’t always feel designed for individuals. Some find deep friendships in support groups. Others find meaning in small victories — a good lab result, a week without pain, a normal holiday with family.

No type of breast cancer experience is easy. Each brings its own mix of medical, emotional, and social challenges. But patients find ways to live — not just to survive — even with difficult diagnoses. And when treatments stretch on, or side effects accumulate, or scans bring unwelcome news, the experience isn’t defined by medical charts. It’s defined by the quiet, stubborn work of showing up to life every day anyway.

Next, we’ll tackle some of the most common questions patients have when they first hear about breast cancer types — clearing up confusion and giving real answers you can hold onto.

Part 12: FAQs About Breast Cancer Types

What is the difference between ductal and lobular breast cancer?

Ductal breast cancer starts in the milk ducts — the channels that carry milk to the nipple — while lobular breast cancer begins in the lobules, the glands that produce milk. Ductal cancers are more common. Lobular cancers, though less frequent, can behave differently, spreading in a more diffuse pattern that’s sometimes harder to detect on imaging. Treatments often overlap, but imaging, surgical planning, and monitoring strategies may be adjusted based on the cancer’s origin.

Is papillary breast cancer considered aggressive?

Generally, no. Papillary breast cancer tends to grow slowly, especially when it’s non-invasive or encapsulated. Even invasive forms of papillary carcinoma usually behave less aggressively than many other types. That said, individual tumors can vary, and invasive papillary cancers are treated with full attention to standard protocols for invasive disease.

Why is inflammatory breast cancer so dangerous?

Inflammatory breast cancer spreads quickly through the skin’s lymphatic vessels, often before a lump forms. It can be misdiagnosed at first as an infection, delaying proper treatment. Even with aggressive therapy — chemotherapy, surgery, radiation — the disease tends to move faster than typical breast cancers, making early detection and prompt treatment absolutely crucial.

Can you have more than one type of breast cancer at once?

It’s rare but possible. Some tumors contain more than one histological pattern (for example, a mix of ductal and lobular features). In even rarer cases, patients may develop two separate breast cancers, sometimes with different receptor statuses or behaviors. When this happens, doctors tailor treatment to address the most aggressive features.

What happens if a tumor changes type during treatment?

It’s uncommon for a tumor to completely change histological type. However, molecular features can shift, especially under pressure from therapies. A cancer that was initially hormone receptor-positive might lose hormone sensitivity over time, or HER2 status might change in rare cases. If a recurrence happens, doctors often re-biopsy to get an updated molecular profile, which can change the next treatment plan.

How important are hormone receptors compared to cancer type?

Both matter, but hormone receptors often have more impact on treatment choices. A hormone receptor-positive cancer — whether ductal, lobular, or otherwise — can be treated with hormone therapies that dramatically reduce recurrence risk. Without hormone receptors, other treatment strategies must be used. Histology still shapes surgical and monitoring decisions, but receptor status drives systemic therapy planning.

What is the survival rate for rare breast cancers?

It depends heavily on the type and stage at diagnosis. Papillary and mucinous breast cancers, for example, generally have excellent survival rates when caught early. Inflammatory breast cancer and metaplastic carcinoma tend to have lower survival rates because of their aggressive nature. However, advances in targeted therapy, immunotherapy, and better supportive care are improving outcomes across many rare types year by year.

Part 13: Final Thoughts

Hearing that you have breast cancer is never simple. Hearing that there are “types” of breast cancer — and that yours carries certain risks, patterns, or treatment needs — can make an already overwhelming situation feel even heavier.

But understanding the type isn’t about assigning blame or sealing fate. It’s about building a map. Each type — ductal, lobular, papillary, inflammatory, triple-negative, HER2-positive — gives doctors more information to guide decisions. It tells them how the cancer might behave, which treatments are likely to work best, and what paths to prepare for.

No two breast cancers are identical. Even patients with the same diagnosis will experience different challenges, side effects, emotions, and victories. That’s why treatment is never one-size-fits-all — and why your care team looks at every detail, from the first biopsy to the final treatment plan.

It’s natural to feel fear when hearing unfamiliar terms. But remember: many types of breast cancer are highly treatable, especially when caught early. Even aggressive types have seen survival improve through research, better therapies, and earlier recognition. And no label — no type, no stage, no statistic — can capture the full story of an individual patient’s strength, hope, and determination.

If you’re facing a new diagnosis or helping someone who is, know this: you are not defined by a pathology report. You are more than a diagnosis. And no matter how rare, how complicated, or how aggressive the type of cancer may be, there are always people ready to fight alongside you — doctors, nurses, researchers, and fellow survivors who have walked their own hard roads.

Understanding the type of breast cancer is a tool. It’s one of many you’ll gather along the way. It doesn’t take away the difficulty, but it does help you move forward — clearer, stronger, and better prepared for the road ahead.