The Breast Cancer Vaccine in 2025: A New Era of Prevention and Hope

- What Is the Breast Cancer Vaccine?

- The Science Behind Breast Cancer Vaccines

- Who Is Eligible for the Breast Cancer Vaccine in 2025?

- Benefits and Limitations: A Balanced Perspective

- How Vaccines Differ from Traditional Breast Cancer Treatments

- Timeline and Development Milestones of the 2025 Vaccine

- What Side Effects Are Associated with the Breast Cancer Vaccine?

- Comparing Breast Cancer Vaccine Types in 2025

- How Vaccines Impact Breast Cancer Recurrence

- Breast Cancer Vaccines and Hormone Receptor-Positive Disease

- Risks, Uncertainties, and Ethical Considerations

- Key Breast Cancer Vaccine Trials to Watch in 2025

- Can the Breast Cancer Vaccine Be Used for Prevention?

- Real-World Use Cases: From Trial to Treatment

- Public Perception and Vaccine Hesitancy

- What’s Next for Breast Cancer Vaccines?

- FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions About the Breast Cancer Vaccine 2025

What Is the Breast Cancer Vaccine?

The concept of a breast cancer vaccine may sound revolutionary, but its foundation lies in well-established immunological science. Unlike traditional vaccines that prevent infectious diseases, cancer vaccines aim to train the immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells by targeting specific antigens—molecules found on the surface of tumor cells but not on normal tissue.

In 2025, several vaccine candidates have entered advanced clinical phases. Most focus on HER2-positive breast cancer or triple-negative subtypes, both of which are known for their aggressive behavior. The vaccines introduce engineered peptides, mRNA sequences, or DNA plasmids that stimulate the body’s T-cells to recognize and attack breast cancer cells selectively, reducing the chance of tumor growth or recurrence.

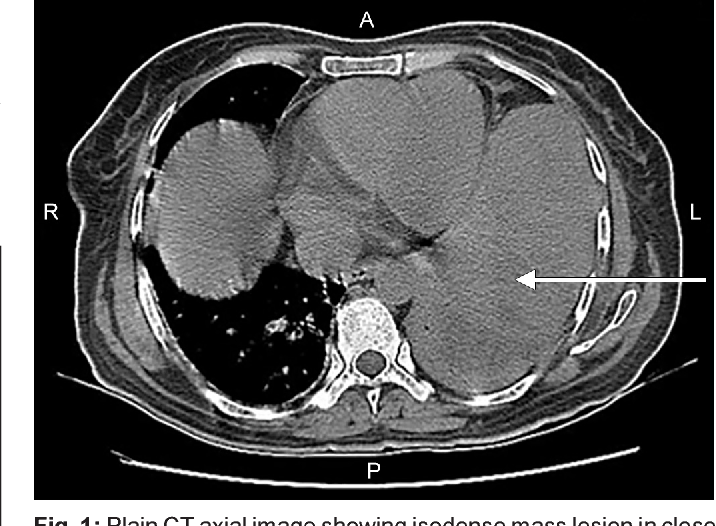

These therapies are not intended to replace existing treatments like chemotherapy or radiation but to enhance the immune system’s ability to prevent cancer from gaining ground again—especially in high-risk or recurrent cases. For patients with a history of breast cancer metastasis to liver, where the disease often returns aggressively, the vaccine approach represents a new frontier in relapse prevention.

The Science Behind Breast Cancer Vaccines

Cancer cells often evade detection because they resemble the body’s own tissues. The challenge has always been finding specific markers—or antigens—that distinguish malignant cells from healthy ones. The most promising vaccines in 2025 target tumor-associated antigens such as HER2, MUC1, and hTERT, which are overexpressed in many breast cancer types.

Vaccines use these antigens to train immune cells—especially cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTLs)—to identify and destroy cancerous tissue. Delivery methods include synthetic peptides, dendritic cell-based platforms, viral vectors, and mRNA formulations, the latter of which gained global recognition during the COVID-19 pandemic and is now adapted for oncology.

These approaches are designed to generate long-term immune memory. The goal is not just to induce a temporary response but to create immune surveillance that prevents tumor recurrence years after initial treatment. This is particularly vital in breast cancer, where dormant cells can reawaken long after remission.

Who Is Eligible for the Breast Cancer Vaccine in 2025?

As of 2025, breast cancer vaccines remain primarily investigational and are generally available through clinical trials or early-access programs. However, eligibility criteria are becoming more inclusive as safety data accumulates. Initially targeted at patients with HER2-positive disease, current trials now encompass triple-negative and hormone receptor-positive subtypes as well.

Vaccines are being offered both as adjuvant therapy (after primary treatment like surgery and chemotherapy) and as preventive therapy in individuals with genetic risk factors such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Some trials are exploring use in patients with no prior cancer history but with strong family history or genetic predisposition.

Age, immune status, and current disease burden also play roles. Patients with active disease may receive vaccines alongside other immunotherapies, while those in remission might be candidates for maintenance or prophylactic vaccination.

Benefits and Limitations: A Balanced Perspective

The idea of a cancer vaccine is compelling, but it is not without limitations. The primary benefit is the potential for long-term immunity—teaching the body to fight recurrence without continuous medication. For survivors, this could reduce dependency on endocrine therapies or toxic chemotherapies and provide peace of mind against relapse.

However, breast cancer is not a single disease. Its subtypes vary genetically and immunologically, making it difficult to develop a one-size-fits-all vaccine. Some patients may not mount a strong enough immune response, especially those who are immunocompromised or elderly. Others may experience autoimmune-like side effects, where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissues.

Moreover, as with any evolving therapy, long-term data is still being collected. Vaccines may eventually reduce metastases, but they are unlikely to be curative on their own—particularly for patients with established metastases, such as those experiencing breast cancer metastasis to skin.

How Vaccines Differ from Traditional Breast Cancer Treatments

Unlike chemotherapy, which attacks rapidly dividing cells indiscriminately, or radiation therapy, which targets localized tumor regions, vaccines are designed to activate the body’s internal defense system to recognize and destroy only cancer cells. This specificity minimizes collateral damage to healthy tissues and typically results in fewer systemic side effects.

Traditional treatments are often limited by toxicity, cumulative dosing restrictions, and long-term complications like cardiomyopathy or early menopause. In contrast, cancer vaccines aim to offer a gentler yet sustained line of defense. They are also less invasive and, in some cases, can be administered as simple intramuscular injections, similar to flu or COVID-19 vaccines.

However, vaccines are not an alternative for every patient. They work best in individuals with minimal residual disease or in remission, where the immune system is not overwhelmed. They are also increasingly being combined with checkpoint inhibitors or targeted therapies to overcome immune suppression and tumor resistance.

Timeline and Development Milestones of the 2025 Vaccine

The road to the 2025 breast cancer vaccine has been decades in the making. Early-stage experiments in the 1990s focused on whole-cell vaccines and heat-shock proteins, which showed promise in animal models but faced translation issues in humans. Over time, focus shifted to peptide and dendritic cell vaccines, with limited success due to poor immune memory generation.

The real breakthrough came in the 2020s with the adaptation of mRNA platforms, borrowed from infectious disease vaccines. These allowed precise delivery of cancer antigens without requiring viral carriers or extended lab culturing. Several candidates, including NeuVax (targeting HER2) and MUC1-based mRNA vaccines, entered phase II and III trials.

In 2025, key clinical trials from institutions like the Cleveland Clinic and Moderna show promising results in disease-free survival and recurrence delay. The FDA has granted fast-track status to several candidates, suggesting commercial availability may be imminent for high-risk patient groups.

Importantly, the same immunological insights driving breast cancer vaccine progress have also inspired approaches in other fields, such as veterinary oncology. For example, ongoing canine trials for brain cancer in dogs mirror many of the human immunotherapy concepts, reinforcing the relevance of cross-species oncology research.

What Side Effects Are Associated with the Breast Cancer Vaccine?

While generally well-tolerated, breast cancer vaccines are not entirely side-effect free. The most common adverse reactions are mild and resemble those of standard vaccines: injection-site pain, low-grade fever, chills, and fatigue. These typically resolve within 24 to 72 hours.

More significant immune-related side effects can include skin rashes, lymph node swelling, or temporary joint pain. In rare cases, patients may develop autoimmune responses, such as thyroiditis or lupus-like symptoms, especially if they have a predisposing immune disorder.

Because the immune system is being activated to recognize antigens also found in small amounts on healthy cells, the risk of immune cross-reactivity remains. Ongoing surveillance in trials closely monitors for such effects, and most studies now include built-in safety protocols and eligibility criteria to minimize risk.

Comparing Breast Cancer Vaccine Types in 2025

Different vaccine platforms are in use or under development in 2025, each with specific advantages. Below is a summary table comparing key vaccine types and their characteristics:

| Vaccine Type | Target Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

| Peptide-Based | Small fragments of tumor antigens | Easy to manufacture; highly specific | Short-lived response; limited memory |

| Dendritic Cell-Based | Patient’s dendritic cells primed with tumor antigens | Personalized; strong immune activation | Expensive; time-intensive |

| mRNA-Based | Encodes tumor antigen directly into patient cells | Rapid development; adaptable to mutations | Storage and delivery challenges |

| DNA Plasmid | Delivers tumor genes via engineered plasmids | Stable; easy to replicate | Less potent in clinical studies so far |

| Viral Vector | Uses modified virus to introduce cancer antigen | Strong immune response | Risk of pre-existing immunity or inflammation |

Each type is being optimized further through combination strategies, including checkpoint blockade, T-cell boosters, and multi-antigen formulations. The field is rapidly evolving, with future generations likely to offer more robust protection and fewer side effects.

How Vaccines Impact Breast Cancer Recurrence

One of the most exciting potentials of breast cancer vaccines is their ability to reduce the risk of recurrence. Unlike conventional therapies, which target tumors already present, vaccines aim to eliminate microscopic cancer cells that may remain dormant after initial treatment. These residual cells are often the culprits behind late relapses, which can happen years—even decades—after apparent remission.

In clinical trials, vaccinated patients showed longer disease-free intervals compared to control groups. In HER2-positive subtypes, early data suggests the recurrence rate may be cut by as much as 30–50% depending on baseline risk factors and combination therapies. Similar trends are emerging for triple-negative patients receiving personalized neoantigen vaccines, which are custom-built from individual tumor profiles.

This approach is especially relevant for patients with a high likelihood of skin or liver recurrence—those with a history of breast cancer metastasis to skin are now being monitored for cutaneous immune responses post-vaccination. Immunologic memory offers a proactive defense against reemergence at these secondary sites.

Breast Cancer Vaccines and Hormone Receptor-Positive Disease

Hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancers are the most common subtype, typically treated with long-term endocrine therapy such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. While effective, these treatments come with side effects that affect quality of life: bone thinning, hot flashes, mood changes, and cardiovascular risks.

Vaccines offer a promising alternative or adjunct to endocrine therapy. Current trials are testing whether vaccination can allow for shorter hormone therapy durations without increasing recurrence. These vaccines often target antigens like MUC1 or survivin, which are expressed in many HR+ tumors.

Initial data suggests that vaccines can delay or prevent recurrence in early-stage HR+ patients, particularly when administered after surgery and radiation. The ability to taper off endocrine therapy without sacrificing protection could significantly improve survivorship for millions of women worldwide.

Risks, Uncertainties, and Ethical Considerations

Despite their promise, breast cancer vaccines raise valid concerns. For one, long-term effects are not fully known. While current safety profiles are reassuring, immune-based therapies may carry late-onset risks, including chronic inflammation or autoimmune reactions. Vigilant post-market surveillance will be critical.

Another issue is accessibility. Personalized vaccines, such as those built from a patient’s unique tumor DNA, are expensive and labor-intensive to produce. This raises ethical questions about healthcare equity, particularly in low-resource settings where breast cancer outcomes are already worse.

Finally, there’s the risk of false hope. Some patients may believe the vaccine is a guaranteed shield, potentially leading to delays in follow-up care or neglect of traditional therapies. Medical teams must manage expectations carefully and reinforce that vaccines are part of a broader treatment continuum—not a silver bullet.

Key Breast Cancer Vaccine Trials to Watch in 2025

Here is an updated overview of major breast cancer vaccine trials active or reporting in 2025:

| Trial Name | Sponsor/Institution | Vaccine Type | Target Population | Current Phase |

| NeuVax (nelipepimut-S) | Galena Biopharma | Peptide (HER2) | HER2-low, disease-free women | Phase III |

| MUC1-mRNA | Moderna + NIH | mRNA | Triple-negative breast cancer | Phase II |

| E75 + GM-CSF Combo | U.S. Military Cancer Institute | Peptide combo | HER2-positive early-stage | Phase II/III |

| AVX901 | Advaxis | Viral vector | Metastatic HR+ breast cancer | Phase I/II |

| Dendritic Cell-Antigen Mix | Cleveland Clinic | Dendritic cell | BRCA mutation carriers | Phase I |

These studies not only examine clinical outcomes but also track immune markers, recurrence timing, and safety indicators. Their findings will shape how vaccines are integrated into standard breast cancer care over the next decade.

Can the Breast Cancer Vaccine Be Used for Prevention?

One of the most forward-looking uses of the breast cancer vaccine is not just in treatment, but in prevention. While most current trials focus on patients who have already had cancer, several programs are now enrolling high-risk individuals with no prior diagnosis. These include BRCA1/2 mutation carriers, women with strong family history, and even some healthy volunteers participating in first-in-human prophylactic studies.

The logic is simple: if we can train the immune system to recognize precancerous or early malignant cells, we may stop breast cancer before it ever starts. Much like how the HPV vaccine dramatically reduced cervical cancer rates, a similar approach for breast tissue antigens could shift the landscape of oncology toward immunoprevention.

This strategy is still experimental and not widely available, but early-phase studies in 2025 show strong immune responses in cancer-free participants. As technologies mature and long-term data accumulates, preventive vaccines may one day be offered alongside mammograms and genetic testing as part of a comprehensive breast health protocol.

Real-World Use Cases: From Trial to Treatment

As breast cancer vaccines begin transitioning from trials to clinics, real-world implementation becomes the next challenge. Integrating a novel biologic into existing care pathways requires collaboration among oncologists, immunologists, pharmacists, and policy makers.

Patients receiving adjuvant vaccines often continue traditional therapies for a time, making coordination critical. Oncology nurses are being trained to manage vaccine-specific side effects, and infusion centers are adapting their schedules to accommodate new protocols.

Insurance coverage and cost considerations are already in discussion, particularly for mRNA-based vaccines that require specialized storage and handling. Pilot programs in academic hospitals have begun administering vaccines under expanded-access designations, allowing patients who do not meet trial criteria to benefit early.

In many ways, this rollout echoes earlier experiences with biologic treatments for other diseases—showing how innovation must be paired with infrastructure to achieve public health impact.

Public Perception and Vaccine Hesitancy

Despite the scientific progress, the idea of a cancer vaccine still faces skepticism. Some patients, especially those wary of newer technologies like mRNA, express concerns about long-term risks, side effects, or experimental status. Others may mistrust pharmaceutical companies or be fatigued by the term “vaccine” due to recent global debates.

Addressing these perceptions is essential. Clear communication, transparent data sharing, and patient education will play a major role in adoption. Oncologists must help patients understand that the breast cancer vaccine is not an unproven experiment but a carefully studied, immune-enhancing tool based on decades of research.

At the same time, the emotional appeal is strong. Many survivors express hope that their daughters—or granddaughters—might one day be spared the pain of diagnosis thanks to a simple injection. As acceptance grows, so too will momentum toward broader uptake.

What’s Next for Breast Cancer Vaccines?

The road ahead is filled with potential. Scientists are already working on multi-antigen vaccines that can target several subtypes simultaneously. There is also growing interest in combining vaccines with personalized tumor sequencing, enabling off-the-shelf solutions that are still biologically tailored to individual patients.

Researchers are also exploring vaccines that integrate with wearable monitoring devices or blood-based biomarker platforms, allowing clinicians to track immune responses in real time. These “smart vaccines” could adjust dosing or antigen targets dynamically, based on patient feedback and tumor evolution.

Beyond breast cancer, this technology will likely spill over into related domains—such as ovarian, prostate, and colorectal cancers—where immunogenic targets exist. And in veterinary medicine, similar breakthroughs may offer hope in parallel domains like brain cancer in dogs and other companion animal tumors.

Ultimately, the breast cancer vaccine is not a finish line but a beginning—a gateway to an era where cancer may be prevented, intercepted, or neutralized before it ever takes hold.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions About the Breast Cancer Vaccine 2025

What is the main purpose of the breast cancer vaccine?

The primary goal is to activate the immune system to recognize and destroy breast cancer cells by targeting specific antigens, reducing the risk of recurrence or even preventing the initial development of the disease in high-risk individuals.

Is the breast cancer vaccine available to the public in 2025?

As of 2025, most breast cancer vaccines are still in clinical trials or limited-access programs. However, some patients—particularly those with HER2-positive or triple-negative breast cancer—can receive them through early-access initiatives in leading cancer centers.

Who is eligible to receive the breast cancer vaccine?

Eligibility depends on the specific vaccine and trial. Typically, patients who have completed initial treatment, those with a high genetic risk (like BRCA mutations), or individuals in remission with high recurrence risk are ideal candidates.

Can the vaccine prevent breast cancer in healthy people?

Preventive use is still in experimental stages. However, early-phase trials show that vaccines can generate strong immune responses in healthy, high-risk individuals. Broader preventive use may become feasible in the next several years.

Does the vaccine replace chemotherapy or radiation?

No. The vaccine is intended to complement—not replace—conventional treatments. It is often administered after surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation, helping prevent relapse or support immune surveillance.

What are the common side effects?

Most people experience mild effects like fatigue, injection-site swelling, or low-grade fever. Rarely, autoimmune-like symptoms can develop, especially in patients with pre-existing immune disorders.

How long does the vaccine protection last?

This is still being studied. Early evidence suggests immune memory may last for years, but booster doses or combination with other therapies might be needed to maintain long-term protection.

Is the vaccine effective against all types of breast cancer?

Not yet. Most candidates focus on HER2-positive or triple-negative subtypes. Research is ongoing to develop vaccines for hormone receptor-positive cancers and less common variants.

Can the vaccine help patients with metastatic breast cancer?

It can help, but results vary. Patients with limited metastasis may respond better. For example, those with breast cancer metastasis to liver may benefit from vaccine-based immune boosting, especially when combined with systemic therapy.

Are breast cancer vaccines safe for older adults?

Generally, yes—though immune response may be lower in elderly patients. Careful screening and monitoring are used to ensure appropriate dosing and minimize risks in this population.

How is the vaccine administered?

Most vaccines are delivered via intramuscular injection, much like flu or COVID-19 vaccines. Some require multiple doses or boosters, depending on the specific trial protocol.

What makes mRNA vaccines promising for breast cancer?

They are fast to produce, adaptable to genetic mutations, and capable of generating strong immune responses. Their success in infectious disease applications has accelerated their development in oncology.

Are there vaccines tailored to my specific tumor?

Yes, personalized vaccines based on your tumor’s genetic profile are in development. These neoantigen vaccines are more expensive and labor-intensive but show promise in targeting residual disease with high precision.

Will insurance cover breast cancer vaccines?

Since most vaccines are still in trials, insurance typically does not cover them. However, as they receive approval, coverage policies will evolve—especially for high-risk patients and recurrence prevention.

How does the breast cancer vaccine differ from vaccines for other cancers?

Breast cancer vaccines are designed to target antigens specific to breast tumors, such as HER2 or MUC1. Other cancer vaccines may target different proteins or use varied delivery methods, but the immune strategy is similar: train the body to recognize and destroy cancerous cells early.