Terminal Cancer Couloir: How To Navigate The Final Stage

- Foreword: Why This Guide Exists

- 1. Understanding Terminal Cancer

- 2. The Patient’s Journey Through the Couloir

- 3. Medical Management and Palliative Care

- 4. Psychosocial and Spiritual Support

- 5. Ethical and Legal Considerations

- 6. Caregiver Support and Resources

- 7. Cultural and Societal Perspectives

- 8. Innovations and Future Directions

- 10. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword: Why This Guide Exists

Let’s start by acknowledging something most people shy away from: talking about death—especially death from cancer—makes us deeply uncomfortable. And yet, for many patients, caregivers, and even clinicians, there comes a time when the question is no longer “How do we beat this?” but rather “How do we live well while dying?”

That’s where the idea of the terminal cancer couloir comes in.

It’s not a medical term you’ll find in your oncologist’s office notes. It’s more of a conceptual shorthand—a passage between two realities. Think of it like a narrow alpine corridor carved through the most unforgiving terrain, treacherous in parts, breathtaking in others. Once you’re in it, there’s no turning around. But there are ways to navigate it with clarity, with agency, and yes, even with a measure of peace.

This guide exists because too often, patients and families find themselves in this space with no map. The medical system may still be focused on treatments. Friends may be too afraid to ask the hard questions. Google returns either cold statistics or overly cheery blog posts. So we’re going to do something different.

We’re going to talk honestly, but with compassion. We’re going to look at how people move through the terminal phase of cancer—not as statistics or case studies, but as human beings with preferences, fears, and moments of unexpected grace. Whether you’re the one facing the couloir or walking beside someone who is, this guide is here to be your final stop: medically sound, emotionally literate, and relentlessly practical.

Now, let’s begin at the beginning.

1. Understanding Terminal Cancer

What Does “Terminal” Really Mean?

The word “terminal” gets tossed around a lot, but let’s be precise. In clinical terms, terminal cancer is an advanced malignancy that is not responsive to curative treatment and is expected to lead to death, typically within a limited timeframe—often measured in months.

But here’s what it doesn’t mean: it doesn’t mean giving up. It doesn’t mean that all medical support stops. And it certainly doesn’t mean the patient’s journey is over. In many ways, this is when the most essential decisions are made, the most intimate conversations had.

If you’re thinking, But how do they even know it’s terminal?—that’s a good question. Doctors make that determination based on tumor progression, treatment history, lab and imaging findings, and patient condition. But prognostication isn’t a precise science. Some people outlive their estimates by years. Others decline more rapidly than anyone predicted. That’s why understanding terminal cancer isn’t just about numbers—it’s about context.

The Timeline Nobody Wants to Talk About

You may have heard phrases like “months to live” or “weeks to months.” These are educated guesses based on population data. But you’re not a population. You’re an individual. Still, some general patterns help orient people:

- Late-stage organ failure (like liver or kidney collapse due to metastasis) typically signals a more accelerated decline.

- Functional decline—less energy, reduced appetite, more time in bed—is often more telling than scan results.

- Symptom escalation, like uncontrolled pain, breathlessness, or delirium, can mark the last chapter.

So what do you do with this information?

Some people want the whole truth as early as possible so they can plan, prioritize, say what needs to be said. Others prefer not to ask. There’s no right answer here—just your answer. But this guide assumes you want to know what you’re facing so you can make the most of the time you have.

How It Feels—for Everyone

For patients, hearing the word “terminal” can land like a guillotine. There’s often a moment of silence, even in a room full of people. Then the flood of questions begins—some spoken, some not.

- What happens to me now?

- How long do I have?

- What will it feel like to die?

- Will I be in pain?

- Will I still be me?

Families, on the other hand, may be caught between needing to support their loved one and processing their own grief. Some go into overdrive, searching for last-ditch clinical trials or experimental treatments. Others freeze. Still others begin to grieve preemptively—what’s often called anticipatory grief.

All of these responses are normal. But if you’re a patient, you deserve to know that this phase of your illness isn’t just about loss. It can also be a time of deep reconnection—with others, with your values, and with the self that lives beneath all the diagnoses and statistics.

Why Language Matters

One last thing before we move on: people sometimes shy away from saying “terminal.” They’ll say “advanced,” or “late-stage,” or just “very sick.” That’s understandable. But euphemisms can obscure rather than comfort. In this guide, we’re going to use the word “terminal” deliberately—not to scare, but to clarify.

Naming things gives us power. It allows us to ask better questions, make wiser choices, and access support systems designed specifically for this phase.

So if you’re ready, let’s keep going. The next part of the journey deals with how people—real people—move through this couloir, not in theory, but in practice.

The Patient’s Journey Through the Couloir

When the map of your life reroutes through the terminal cancer couloir, there’s no universal path to follow. Each person’s passage is shaped by their beliefs, body, medical history, and the terrain of their relationships. Still, there are patterns—emotional, psychological, practical—that appear again and again. Understanding these doesn’t eliminate the pain, but it can illuminate the road.

From Diagnosis to Meaning

For many, the moment terminality is acknowledged marks a distinct before and after. It’s not just another appointment or scan result. It redefines time, narrows focus, and often brings clarity to what truly matters. Some describe a fog lifting. Others feel a sense of falling—like the ground beneath them has simply disappeared.

What follows isn’t linear. People cycle through complex responses. Anger doesn’t always come before acceptance. Denial can return even after months of lucidity. But generally, there’s a transition from fighting to live to living while dying—a shift from the language of war to the language of presence.

And that shift, while painful, can be incredibly liberating.

There’s often a surprising intimacy in these moments: the unspoken becomes spoken, long-avoided conversations finally unfold, and clarity sharpens into things like “I want to die at home,” or “I need to see the ocean again,” or “I’m done with more chemo.”

You might ask: Is there a “right” way to do this? Should I be more at peace by now? No, and no. Some people embrace the process of letting go with an almost spiritual readiness. Others grip tightly until the very end. The truth is, acceptance isn’t an endpoint; it’s a posture that may come and go, like a tide. The key isn’t to force yourself to be serene—it’s to be real.

Decision Points Along the Way

One of the cruel ironies of terminal cancer is that even after curative treatments are no longer on the table, the decisions don’t stop. If anything, they multiply.

Do I stop treatment altogether?

What does “comfort-focused care” actually look like?

Is this hospital stay necessary—or even helpful?

Should I tell people how bad it is, or protect them?

You may feel like you’re navigating a minefield with no clear signals. That’s normal. But the couloir is also the place where the quality of decision-making starts to matter more than the quantity of medical interventions. It’s not about extending time at all costs. It’s about aligning your time with what matters most to you.

Consider this: every decision is a way of shaping the end of your story. Saying no to one more hospitalization might not feel like an act of power—but it can be. So can choosing hospice over one more round of radiation. So can telling your doctor, “I’m done chasing things that make me sicker.”

And let’s pause here on hospice, because that word gets loaded with misunderstanding.

Hospice isn’t about giving up. It’s not a last resort. It’s a shift in focus—from prolonging life to supporting life in its final chapter. It brings pain control, emotional support, home visits, and respite for caregivers. The earlier it’s integrated, the more it can help. But it requires an emotional reckoning: an acknowledgment that the goal has changed.

Similarly, advance care planning is often avoided until it’s too late. Yet writing a living will, designating a healthcare proxy, and talking through your preferences for end-of-life care can save you and your loved ones a great deal of uncertainty and suffering. It’s not a formality. It’s a lifeline—to your autonomy, your voice, your sense of agency.

Coping and Reorientation

Some people in the couloir turn toward meaning-making as a way to cope. That might look spiritual—prayer, meditation, rituals of closure. But it might also be deeply personal: writing letters to children, planning a celebration-of-life event, or simply telling your favorite stories one more time.

Others find strength in routines. Making tea every morning. Watering the plants. Rewatching a favorite show. These small rituals offer structure when everything else feels unstable. They can anchor the self, reminding you that even when the future is collapsing, the present is still yours.

You might wonder: Is it wrong to laugh? To still want things? Absolutely not. In fact, joy and longing can become sharper at the end of life, not dulled. Many people report experiencing moments of astonishing clarity and tenderness. Not despite their prognosis—but because of it.

There’s also the question of how much to share, and with whom. Not everyone needs—or deserves—every detail. You get to curate your truth. You get to decide who gets your energy, and when. It’s okay to protect your peace. It’s okay to say, “I don’t want to talk about cancer today.” The couloir doesn’t require you to become an open book.

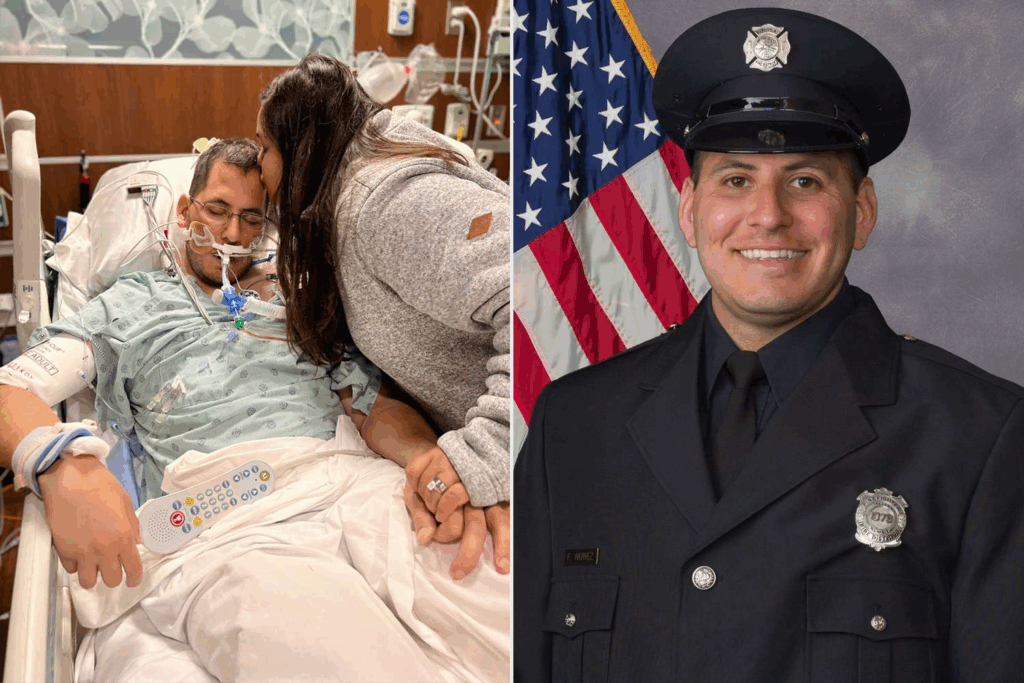

Walking Beside the Patient

Let’s not forget the caregivers—the spouses, children, siblings, friends. Their journey, while different, is equally complex. They’re not just companions; they’re witnesses, decision-makers, sometimes interpreters between the patient and the healthcare system. Their presence can be steadying, but they, too, need acknowledgment, support, and rest.

Whether you’re a caregiver or patient, the topic of advanced care overlaps heavily with How Fast Oral Cancer Spreads, particularly in terms of progression and comfort priorities.

If you’re one of them, don’t wait for someone to give you permission to take care of yourself. The patient may feel guilt for how their illness affects you. You may feel guilt for resenting your role. That’s not failure. That’s humanity.

What matters is not perfection, but presence.

Medical Management and Palliative Care

Let’s dispel a persistent myth right out of the gate: Palliative care isn’t just “what they do when there’s nothing left to try.” It’s not a white flag. It’s not a soft form of abandonment. Palliative care is a specialized, evidence-based branch of medicine that focuses on reducing suffering and improving quality of life—for people of any age, at any stage of serious illness, including (and especially) the terminal phase.

In the couloir, this isn’t optional. It’s foundational.

The Shift in Medical Priorities

There’s a noticeable pivot when someone crosses into the terminal phase. Previously, the emphasis may have been on tumor shrinkage, lab values, or getting into a clinical trial. But when curative efforts have been exhausted or declined, the medical team must reorient. The metrics of success change.

Now we ask:

- Is your pain controlled?

- Are you sleeping at night?

- Can you enjoy your food?

- Do you have the energy to talk to your family, to go outside, to listen to music?

This is medicine rehumanized. And ironically, it often takes more skill to manage symptoms at the end of life than to write another chemotherapy order. Good palliative care is not passive. It’s attentive, strategic, and highly individualized.

Managing Pain—More Science Than People Think

Pain is often the first and loudest concern. And with good reason. Cancer pain can come from many sources—tumor invasion, nerve compression, bone metastases—and it can be constant, or it can flare without warning. But the good news is that pain can almost always be controlled.

Opioids remain the cornerstone of cancer pain management, despite public confusion due to the opioid epidemic. Terminal patients are not at risk of becoming addicted in the conventional sense. The real risk is undertreatment—either due to clinician hesitancy or outdated fears among patients and families.

What does good pain management look like? It looks like:

- Morphine or hydromorphone for steady, baseline pain.

- Short-acting doses (“breakthrough meds”) for flares.

- Adjuncts like gabapentin for nerve-related pain.

- Anti-inflammatories or even steroids for tissue swelling.

The goal is always comfort with alertness—enough relief to live, not just to sedate. And that’s a balance you can strike with the right team.

Navigating Other Symptoms: Not Just Pain

Pain may be king, but it doesn’t rule alone. Nausea, constipation, shortness of breath, fatigue, confusion—these are frequent visitors in the couloir, and each can erode quality of life in its own unique way.

Take nausea: Sometimes it’s due to the cancer itself, but it can also stem from meds, liver dysfunction, or bowel blockages. The treatment might involve antiemetics like ondansetron, but also dietary adjustments or even radiation to shrink a mass that’s pressing on the stomach.

Or consider breathlessness—what clinicians call dyspnea. This one can be especially distressing. Not being able to get enough air triggers panic, even if oxygen saturation is technically fine. Low-dose opioids can ease the sensation of breathlessness. Yes, opioids for breathing. It sounds counterintuitive, but it works—by changing how the brain perceives air hunger.

Then there’s fatigue, which isn’t just “being tired.” It’s systemic depletion. It doesn’t go away with a nap. It can stem from anemia, cachexia (muscle wasting), poor nutrition, or the sheer energy cost of illness. There are no magic fixes, but sometimes small interventions—a transfusion, a stimulant, gentle physical therapy—can restore a sense of agency.

Symptom control is both art and science. It requires creativity, persistence, and a team that listens closely. If you feel like you’re being brushed off—told to “just take Tylenol” when your bones feel like they’re breaking—advocate harder, or find someone who will.

Hospice vs. Palliative: What’s the Difference?

People use these terms interchangeably, but they’re not synonyms.

- Palliative care can be given alongside active treatment. It’s a medical specialty focused on symptom management, communication, and quality of life.

- Hospice care is a Medicare-defined program for people with a life expectancy of six months or less, who have chosen to forgo curative treatments.

In practice, hospice brings the palliative philosophy home—literally. It offers:

- Regular visits from a nurse case manager.

- A 24/7 on-call line for symptom crises.

- Home delivery of medications and equipment.

- Aides to help with bathing and hygiene.

- Spiritual care and grief support for families.

Hospice can be done at home, in a facility, or even in the hospital, depending on what’s available. It’s a wraparound model, and when started early, it doesn’t just improve comfort—it often extends life.

Yet people delay it. Why? Because saying yes to hospice feels like saying no to hope. But hope doesn’t have to die when cure is off the table. It just changes shape. Hope for peace. Hope for control. Hope for a good goodbye.

Integrative Therapies: More Than Placebos

Let’s talk about acupuncture, massage, music therapy, aromatherapy. These often get dismissed as “alternative,” but within palliative care, they’re increasingly seen as legitimate adjuncts. Why? Because evidence shows they reduce pain, anxiety, and nausea—with minimal side effects.

- Acupuncture may modulate endorphins and calm the autonomic nervous system.

- Music therapy can lower cortisol and evoke memories, even in late stages of decline.

- Gentle massage can reduce agitation and provide human touch in a time when much touch becomes clinical.

Are these treatments “essential”? Maybe not in the technical sense. But when you’re trying to optimize someone’s final weeks or days, small comforts can mean everything. And choosing them can be another way of asserting control, of saying: This is how I want to feel. This is how I want to be treated.

Psychosocial and Spiritual Support

If the body leads the early part of the journey through the terminal cancer couloir, the mind and spirit begin to take the foreground as time narrows. You may still be dealing with medications and symptoms—but increasingly, it’s the intangible things that occupy the most space: fear, memory, regret, love, legacy. The inner life becomes the primary terrain.

So why is this part so often overlooked?

Because it’s hard to talk about. Because physicians may not be trained in existential distress. Because family members want to keep morale high. Because “How are you feeling today?” is easier to answer when it refers to pain or appetite, not loneliness or dread.

And yet, for many, this is the phase when life becomes most distilled.

The Weight of Being Aware

Let’s begin with something that deserves to be said out loud: Knowing you are dying is a specific kind of psychological weight. It changes how you perceive time, how you relate to others, and how you think about yourself.

Some people experience what’s known as anticipatory grief—a slow grieving of oneself. Not just the future that won’t be, but also the parts of life you’re already losing: physical independence, identity as a provider or partner, control over your days. That grief can arrive quietly or crash in like a wave.

Others struggle with something harder to name: the dissonance between being treated as a “patient” and feeling like a person. Medical systems tend to focus on symptoms and logistics. But what about sorrow? What about fear? What about wondering, at 3am, whether you’re ready—or what being ready even means?

These aren’t psychiatric symptoms. They’re signs of consciousness.

It’s not uncommon to experience existential distress: anxiety, helplessness, or an overwhelming sense of what’s been left undone. That doesn’t mean you’re depressed (although depression is certainly possible). It means you’re awake to the magnitude of your life—and its ending.

If that sounds familiar, know this: There are supports. There are clinicians trained in exactly these challenges. And acknowledging them isn’t weakness. It’s one of the most courageous acts in this whole journey.

Talking to Someone—And Not Just Anyone

Therapy may not have been your thing in the past, but in the couloir, it can become a lifeline. Palliative care teams often include psychologists or licensed counselors who specialize in end-of-life work. Their job isn’t to “fix” your thinking. It’s to witness it, challenge it, and offer tools to help you carry it more easily.

Support groups—whether in-person or virtual—can also be a source of unexpected connection. You’re suddenly among people who get it, who won’t flinch when you say “hospice” or talk about funeral plans. These spaces can be grounding. And if you’re not up for groups? Even one deep, ongoing conversation—with a therapist, a chaplain, a wise friend—can help you make emotional sense of what’s happening.

If you’re a caregiver, you’re part of this too. Watching someone you love approach death is its own psychological storm. You might feel helpless, guilty, angry, fiercely loving, completely numb—or all of that in one day. You also need space to talk, to feel, to grieve. Caregiver counseling exists, and it matters.

The Role of Spirituality (Whether or Not You’re Religious)

Let’s be clear: spiritual support is not the same thing as religion. Religion can be a part of it, certainly—but spirituality in this context refers to the part of you that asks: What does this all mean? What happens after I die? Was my life enough?

These are not abstract questions when you’re in the couloir. They become embodied. And avoiding them doesn’t make them go away—it just makes the silence louder.

For some, a faith tradition provides structure and comfort. Rituals. Clergy. Sacred texts. A sense of community and afterlife. Others find spiritual solace in nature, music, legacy work, or simply being present with loved ones. What matters is that you have the space to ask the questions that surface. Even the unanswerable ones.

You might also want to see how other end-stage cancers present, such as Stage 4 Appendix Cancer, which shares some systemic features and palliative dilemmas.

Hospitals and hospices often have chaplains—not to proselytize, but to walk beside people asking spiritual or existential questions. You don’t need to believe in God to talk to one. You just need to be human.

And if you’re feeling things you can’t name—restlessness, disconnection, dread—that’s part of it too. Sometimes spiritual suffering shows up as a vague ache, a loss of meaning. Naming it can be the first step toward easing it.

The Tension in Families

Families mean well. They want to support you. But they’re grieving too—sometimes loudly, sometimes quietly, sometimes in ways that don’t match your needs at all.

You may find yourself managing their emotions instead of your own. Or biting your tongue to avoid upsetting them. Or watching old tensions resurface, even as time grows short.

This is a delicate dance.

Try, when possible, to be clear about what you want—and what you don’t. If you’re the patient, you don’t need to entertain every visitor or reassure every friend. You get to say, “I’d rather talk about something else today,” or “Please don’t tell me to stay positive.” You get to define the emotional temperature of your own space.

And if you’re the caregiver or loved one, remember: being present doesn’t always mean talking. Sometimes presence means just sitting. Listening. Holding a hand without needing to fill the silence.

There may also be last conversations you want—or need—to have. This can be the time to say what wasn’t said. Apologies. Gratitude. Forgiveness. “I love you.” “I remember.” “It’s okay.” These are not clichés. They are anchors.

The Possibility of Peace

Let’s not romanticize this. Dying is not easy. But it can be meaningful. It can be honest. It can be deeply human.

And sometimes, people find peace—not because they’ve tied up every loose end, but because they’ve made peace with the fact that not all things can be tied. Because they’ve named what mattered. Because they’ve felt seen and heard.

This is why psychosocial and spiritual care aren’t “extras.” They’re not afterthoughts. They are central to living the final chapter with as much fullness as possible.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

There comes a moment in every terminal journey—sometimes early, sometimes abruptly—when the clinical gives way to the ethical. Not because medicine has nothing left to offer, but because the questions shift. Not “what can be done?” but “what should be done?” Not “what is possible?” but “what is right—for me, for now?”

If you’re reading this as a patient, you may already feel the tension: a desire for autonomy met by a system that tends to operate on momentum. If you’re reading as a caregiver, you might be carrying the emotional weight of decision-making for someone you love. In either case, it’s essential to understand this truth: your values are not a side note to care. They are the center of it.

The Right to Choose—and the Right to Say No

One of the most important principles in medicine is patient autonomy—the right of a competent adult to make decisions about their own care, even if others disagree. This includes saying no. No to more scans. No to another hospitalization. No to interventions that prolong life without preserving quality.

In the couloir, this can be one of the most powerful forms of self-definition. Choosing comfort over cure is not surrender. It’s a shift in goalposts. It says: I want to live well, not just longer. And you are allowed to make that choice without apology.

Of course, making that choice can feel fraught—especially if family or even clinicians resist. This is where clarity matters. Saying what you want, in writing, and having that conversation before a crisis hits can prevent conflict later on.

Advance Directives: Not Just Bureaucracy

Let’s get practical. If you haven’t already, now is the time to complete your advance care planning documents. Yes, they’re legal forms. But they’re also emotional blueprints—for your care, your dignity, and your control.

At minimum, this includes:

- A living will: a document stating what types of life-sustaining treatments you would or would not want if you were unable to communicate.

- A healthcare proxy (or durable power of attorney for healthcare): someone you trust to make decisions on your behalf if you’re incapacitated.

The most common regret families express after a death isn’t about medicine—it’s about uncertainty. “I don’t know what she would have wanted.” “We never talked about this.” These documents spare your loved ones that burden.

And here’s the thing: These conversations don’t have to be morbid. They can be clarifying. Even loving. They give shape to your values. “If I can’t speak, I want music in the room.” “I don’t want machines keeping me alive.” “I want to be at home if possible.” These are not small preferences. They are the terms on which you meet the end of your life.

Medical Aid in Dying: A Difficult, Legal Reality

This is a complicated and controversial topic, but it would be intellectually dishonest not to include it. In some jurisdictions—such as parts of the U.S., Canada, Switzerland, and elsewhere—medical aid in dying is legal under strict conditions. This allows a mentally competent, terminally ill adult to request a prescription for a medication that will end their life.

Not everyone wants this option. Not everyone qualifies. But for some, just knowing it’s available provides a sense of peace. It restores a measure of control in a process where so much else has been lost.

That said, access is deeply uneven. Legal, ethical, and cultural opinions vary widely. If it’s something you’re considering, seek guidance from a physician, legal advisor, or palliative care specialist in your region. Make sure you understand the process—and the implications. This is not a decision to be made in isolation or haste.

When Capacity Is in Question

Cognitive decline can accompany terminal cancer—especially with brain involvement, medications, or metabolic shifts. When a person can no longer make their own decisions, the existence of a designated healthcare proxy becomes vital.

But here’s where it gets tricky: families don’t always agree. If there are no legal documents, conflict can arise over “what mom would have wanted.” The best way to prevent this? Name someone. Have the conversation early. Be specific.

If you’re the designated decision-maker, remember that your role is to honor the patient’s wishes, not your own instincts. This distinction can feel subtle but becomes crucial under stress. The best proxies act not as decision-makers but as advocates for previously expressed preferences.

The Legal Landscape of Death

There are a few other practical legal matters worth addressing—ones that aren’t glamorous, but will one day matter deeply to the people you love.

- Wills and estate planning: Who inherits what? Who handles your affairs? These decisions remove uncertainty and potential conflict.

- Digital legacy: Have you documented passwords, account information, instructions for social media or email?

- Final arrangements: Burial or cremation? A specific kind of ceremony? Even if you think your family “will figure it out,” articulating your preferences can provide a roadmap through grief.

These aren’t just financial details. They’re acts of care. They say: I thought of you. I tried to make this easier.

Ethics at the Bedside

Even with everything in order, ethical tensions can arise. A patient refuses food. A family wants “everything done” despite a DNR order. A doctor proposes an intervention that feels aggressive or unwanted.

In these moments, palliative care teams often serve as mediators—balancing medical insight with respect for values. If conflict arises, ethics consults can be requested in most hospitals. These are not about deciding who’s right. They’re about aligning care with goals.

It’s okay to ask for these conversations. In fact, it’s essential.

Caregiver Support and Resources

If the patient is at the center of the couloir, caregivers walk just behind the shoulder—close enough to support, far enough to witness. It’s a position of love, but also enormous complexity. And yet, even in a world flooded with cancer information, the caregiver’s experience is often sidelined, reduced to logistics or platitudes.

Let’s change that.

Caregiving during terminal illness is its own profound journey. It is physical, emotional, moral, and relational. It demands more than most roles in medicine or family life—and it’s frequently done with no formal training, little rest, and even less recognition.

So if you’re reading this and caring for someone who’s dying: yes, this part is for you.

You Become the Everything

Caregivers often become the de facto case managers, home health aides, advocates, nurses, drivers, and emotional anchors. You’re there during appointments, asking the questions your loved one is too exhausted—or too scared—to voice. You’re monitoring medication doses, rearranging furniture to make room for a hospital bed, calling insurance companies at 8:01 AM.

And sometimes, you’re doing all this while working, parenting, grieving.

It’s not uncommon to feel like the system expects you to act like a professional and a saint, when you are, in fact, a human being. One who is deeply tired. One who might feel guilty for wanting a break. One who wonders—quietly—how long you can do this.

Let’s make something clear: feeling overwhelmed doesn’t mean you’re failing. It means you’re doing the hardest job most people never see.

Burnout: The Quiet Erosion

Caregiver burnout doesn’t arrive like a lightning bolt. It accumulates. It builds in the space between sleepless nights and emotionally loaded days. It lives in skipped meals, postponed medical checkups, and suppressed emotions.

You may notice it as irritability, brain fog, withdrawal. Or you may not notice it until you snap at the hospice nurse or burst into tears over the laundry. That’s not moral weakness. That’s human physiology under pressure.

And here’s where it gets dangerous: many caregivers feel they don’t have “the right” to burn out because the person they love is the one dying. But the truth is, if you go down, the whole system around that patient falters. You are not expendable. You are essential.

Which means you need help. Not just permission to get help—but a system around you that makes that help accessible.

Finding—and Accepting—Support

Let’s talk about what’s available. Because while it may not be enough, there are resources. The key is to ask early—before you’re desperate.

- Hospice agencies often provide a nurse case manager, a social worker, and aides who can assist with bathing, hygiene, and light care tasks. Don’t overlook how transformative this can be, especially as the patient becomes more dependent.

- Respite care is a critical, underutilized service. Some programs will cover short-term inpatient stays so caregivers can rest. Others offer volunteers to sit with the patient while you leave the house. You are not selfish for needing this. You are strategic.

- Support groups, whether online or local, connect you with others walking a similar path. Not everyone wants to talk—but if you do, these groups can be lifelines.

- Counseling is not indulgence. If you’re crying in the car or feeling numb to everything, talking to a professional isn’t weakness. It’s maintenance.

- Financial help may be available through cancer societies, religious organizations, or local nonprofits. Caregiving often takes an economic toll—missed work, out-of-pocket costs, increased utility bills. It’s okay to seek aid.

And then there’s the quieter help. The friend who brings food and doesn’t need to talk. The neighbor who walks your dog. The cousin who offers to handle paperwork. Let them. Let them. Let them.

Guilt, Grief, and the Myth of Doing It Perfectly

Caregivers often carry guilt like a second spine. Am I doing enough? Should I have caught that sooner? Was it wrong to snap yesterday?

Here’s the hard truth: there is no “right” way to walk someone through death. You will make mistakes. You will have bad days. You will long for rest or even—quietly—an end. That doesn’t make you cruel. It makes you exhausted and heartbroken.

What matters isn’t perfection. It’s showing up again and again. And if you need a break to keep showing up, take the break. The patient’s love for you is not measured in how many hours you stand vigil without flinching. It’s measured in presence, in truth, in the grace of being real.

And yes, you are grieving—already. This is anticipatory grief, and it’s real. It may come with guilt, or numbness, or irrational thoughts. You may imagine the funeral. You may dream about being free. This is not betrayal. It’s how the psyche copes with impossible proximity to loss.

After the Death: Caregiver, Then What?

Most people assume caregiving ends when the patient dies. In one sense, that’s true. But in another, it’s just a transition. Many caregivers report feeling adrift after the funeral. No more meds to administer, schedules to manage, tasks to fulfill. Just a haunting silence.

This is when the grief can hit with full force.

Hospice programs often include bereavement support for up to a year. Take it. Let yourself be accompanied, just as you accompanied someone else. Your needs don’t stop at the edge of the couloir. You’ve lived through something enormous. You deserve to heal.

Cultural and Societal Perspectives

Dying is a universal human experience. But how we die—and how we make sense of dying—is anything but universal. Culture, religion, geography, healthcare access, and even the language we speak all shape the terminal experience in profound ways. And when we talk about the couloir, we’re not just talking about medicine. We’re talking about meaning. About systems. About stories.

For those wrestling with the emotional weight of timing, Hyperthermia for Treating Breast Cancer in Dogssurprisingly offers an illustrative case of prolonging quality of life in advanced scenarios — even in animals.

So let’s step back and look around: What does it mean to die of cancer in a society that celebrates youth and productivity? What happens when the way you want to die doesn’t align with what your culture, your family, or your healthcare system believes is “appropriate”?

There are no single answers here—only lenses through which we can understand this part of the journey more deeply.

Cultural Norms Around Death

In some cultures, death is openly discussed, ritualized, and even celebrated. In others, it’s wrapped in silence, seen as taboo or even a moral failing. These differences matter—because they influence how comfortable people feel speaking openly about their illness, asking for help, or planning for the end.

In Japan, for instance, silence and stoicism are often valued in terminal care—patients may avoid discussing prognosis out of deference to the group. In contrast, some Western settings prioritize individual autonomy, emphasizing disclosure and informed decision-making.

In many Latin American and African cultures, extended family plays a central role, with the dying person often surrounded by relatives who participate in care and mourning. In contrast, in high-income Western nations, the dying process can become medicalized, occurring in facilities far removed from everyday life.

These aren’t just differences in setting. They reflect different ideas about what a good death is—and who gets to define it.

Language: The Words We Use (and Avoid)

It’s striking how much language shapes experience. Consider the difference between saying “He’s dying” versus “He’s transitioning.” Or “terminal cancer” versus “advanced illness.” Or “no more treatment” versus “comfort-focused care.”

Sometimes softer language is used out of compassion. Sometimes it’s used to avoid reality. But if you’re the one facing death—or helping someone who is—you deserve clarity, not euphemism. Precision is not cold; it’s kind. It allows for real decisions, grounded in real understanding.

And in some cultures or families, there may be no word at all for hospice, or for the kind of death we’re talking about. This absence can leave people feeling isolated or confused. One way to counter that? Start where people are, not where we think they should be. Use language that resonates—then build clarity from there.

Societal Support Systems: Infrastructure Shapes Experience

Let’s talk about systems.

Where you live can determine whether you die at home or in an ICU. It can dictate whether your pain is managed skillfully or left to escalate. It can mean the difference between coordinated hospice support and a desperate family doing their best with Google searches and expired medications.

In countries with universal healthcare and integrated palliative systems—like the UK, Canada, or parts of Scandinavia—patients may have earlier access to comfort care, fewer unnecessary hospitalizations, and more consistent support for caregivers. In the U.S., access to hospice often hinges on insurance policies and the quirks of Medicare regulations.

And even within one country, disparities are vast. Rural patients may face hours of travel to access palliative specialists. Black, Indigenous, and other marginalized groups often receive less pain medication, are referred to hospice later, and face cultural misalignment with providers.

These aren’t theoretical issues. They shape real people’s final days. Recognizing this doesn’t mean accepting it—it means advocating better, pushing harder, asking why the best care isn’t yet the standard everywhere.

Religion and Spiritual Legacy

In many traditions, death is not an end but a transformation.

- In Islam, death is a return to God, with an emphasis on surrender and prayer.

- In Hinduism, it’s a passage into rebirth—rituals are often performed to guide the soul.

- In Buddhism, mindfulness and detachment prepare the dying person for transition.

- In Christianity, death is both grief and hope, a reunion and a homecoming.

These frameworks influence everything from pain tolerance to care preferences. Some traditions resist sedation, valuing lucidity at the time of death. Others emphasize confession, absolution, or ritual washing.

Spiritual customs also shape how grief unfolds—what is said, what is worn, how the body is treated, who gathers, and for how long.

And for the nonreligious? There is still ritual. Still legacy. Still the deep human need to locate meaning in the ending of a life.

The key is to recognize what matters to the person dying—not to generalize, but to ask. Not “What does your religion say?” but “What would be meaningful for you as this chapter closes?”

The Myth of the “Right” Death

Let’s end with a caution: There is no universally right way to die. There is no perfect script. In trying to “do it well,” some people inadvertently burden themselves with impossible standards—peaceful, pain-free, surrounded by love, reconciled, ready.

Sometimes that happens. Sometimes it doesn’t.

And what’s more: culture can create pressure. Pressure to be brave. To be silent. To be faithful. To be stoic. But you are allowed to be scared. Angry. Unfinished. You are allowed to die as yourself—not as an ideal.

If we want to build better systems, we must make room for pluralism—for people to die in ways that reflect who they are, not who we think they should be.

Innovations and Future Directions

If there’s one truth about the terminal cancer couloir that most people underestimate, it’s this: even the end of life is a space for innovation. Not in the sense of disruption for disruption’s sake, but in how we make dying more humane, more aligned with dignity, and more responsive to the complexity of what patients and families actually need.

The fact that we are talking more openly about death now than a generation ago? That’s innovation. The integration of palliative care into cancer clinics? Innovation. The emergence of digital legacies, telehospice, and AI-assisted symptom tracking? All of that, too.

Even here—especially here—progress matters.

A Quiet Revolution in Palliative Medicine

Over the past two decades, palliative care has moved from the margins of medicine to something closer to the mainstream. Major cancer centers now embed palliative specialists early in treatment plans. Studies show that early palliative involvement not only improves quality of life, but can extend it, in some cases more than chemotherapy.

We’re also seeing the professionalization of the field. Once a patchwork of well-meaning generalists, palliative care now draws highly trained clinicians with expertise in symptom science, ethics, communication, and existential care. This isn’t “soft medicine.” It’s precision care of the body and soul.

Still, access is uneven. Rural areas, under-resourced hospitals, and low-income regions may offer little or no palliative support. One frontier of innovation, then, isn’t just clinical—it’s structural. It’s about scaling what works. Making sure a peaceful death doesn’t depend on your ZIP code.

Technology at the Bedside

Technology may not be the first thing you associate with terminal care—but it’s rapidly reshaping the landscape in ways both subtle and profound.

- Telehospice has expanded rapidly, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual visits allow nurses, social workers, and chaplains to support patients remotely—especially critical for rural or mobility-limited individuals.

- AI-assisted symptom tracking tools are now in use, helping teams monitor pain, anxiety, sleep, and medication efficacy between visits. Some apps even alert clinicians when symptom thresholds are breached.

- Digital legacy platforms are helping people document their lives—through voice messages, written reflections, or video journals. These aren’t just memory aids; they’re acts of authorship, offering loved ones a way to connect beyond time.

And then there are more experimental tools. Some palliative researchers are exploring VR for immersive experiences—allowing bedridden patients to “travel” virtually or experience calming environments. Others are trialing wearable devices that fine-tune medication dosing or monitor for distress.

Tech won’t replace the human touch. But it may help preserve and extend it.

Reimagining the Place of Death

Where people die matters. For decades, most deaths occurred at home. Then came the rise of hospital deaths—often high-tech, high-intensity, and, for many, at odds with how they wished to go.

Now, we’re seeing a reversal. Not a return to “home at all costs,” but a thoughtful rebalancing.

- Hospice and palliative care units in hospitals now offer low-stimulation, comfort-prioritized environments.

- Death doulas—non-medical companions trained in end-of-life support—are helping bridge gaps in emotional care.

- Community-based programs in places like Kerala, India, or British Columbia offer mobile palliative teams that bring care directly to people’s homes.

Even urban planning is getting involved. Some cities are experimenting with “compassionate communities” models, where neighborhoods collectively support terminal patients—sharing tasks, emotional presence, and rituals.

The message behind all of this? Dying should be treated as a relational, social experience—not just a medical event.

Legal and Policy Horizons

Policy is often the last to catch up—but there are promising shifts underway.

- Earlier hospice eligibility is under review in many systems, with efforts to remove the artificial “six-month prognosis” requirement that keeps people from accessing help when they most need it.

- Expanded aid-in-dying legislation is being debated in jurisdictions around the world. While controversial, the push for choice at the end of life reflects a broader movement toward patient-centered care.

- Palliative care mandates are being introduced in cancer centers, long-term care homes, and even prisons—reflecting the idea that the right to a good death is a matter of equity, not privilege.

At the same time, public health frameworks are beginning to integrate death into their models—not just as a tragic endpoint, but as a continuum that deserves planning, resourcing, and normalization.

The Cultural Turn: Death Literacy

Finally, something quieter but just as significant: our collective willingness to talk about death is changing.

Books like Being Mortal, movements like “Death Cafés,” podcasts, documentaries, subreddits—these are all parts of a rising death literacy. A willingness to ask, What does it mean to die well? And just as importantly: How do we support each other in the process?

This is perhaps the most vital innovation of all: not a gadget or a policy, but a shift in the social narrative. One that acknowledges death not as failure, but as a human milestone. One that restores storytelling, ritual, and community to their rightful place in the dying process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What’s the difference between palliative care and hospice care?

Palliative care is specialized medical support focused on comfort and quality of life, available at any stage of serious illness—even alongside curative treatment. Hospice care is a specific type of palliative care reserved for people with a life expectancy of six months or less who are no longer pursuing curative treatment. In short: all hospice is palliative, but not all palliative is hospice.

How is pain managed at the end of life—and will I be heavily sedated?

Pain can almost always be controlled, typically with a combination of opioids and other symptom-specific medications. The goal isn’t to sedate you into unconsciousness unless that’s what you want. The aim is clarity and comfort—not absence. Dosages can be titrated so that you’re alert enough to have conversations and make choices, while still staying out of agony.

Can I still receive treatments like chemotherapy or radiation if I’m in the terminal phase?

Yes, but only if those treatments are likely to improve quality of life, not just extend time. For example, a short course of radiation might relieve bone pain. The key is re-evaluating every intervention against the question: Will this help me feel better? If not, it’s okay to decline.

What documents should I prepare to make sure my wishes are followed?

At minimum, you should complete an advance directive (which may include a living will) and designate a healthcare proxy. If you have preferences around CPR, intubation, or artificial feeding, those should be spelled out clearly. Also consider your estate planning: a will, power of attorney, and instructions for digital assets.

How do I talk to my children or grandchildren about my terminal illness?

Gently, honestly, and in age-appropriate terms. Children sense when something is wrong. Giving them language—and the space to ask questions—often reduces anxiety more than hiding the truth. It’s okay to say, “I’m very sick, and the doctors don’t think I’ll get better,” and to let love guide the rest.

What are signs that it might be time to transition to hospice care?

If treatments are causing more harm than benefit, if symptoms are escalating, or if your goals have shifted from survival to comfort, it may be time. Other clues: increased hospital visits, declining function, and the feeling that your life is more about managing illness than living.

Is it normal to feel relief mixed with guilt as a caregiver?

Yes. Profoundly yes. Relief doesn’t mean you wanted your loved one to die. It means you’ve been carrying something immense—and your body and mind are responding to the lifting of that weight. Guilt is common, but rarely warranted. You showed up. That matters more than perfection.

Are there financial resources for patients and caregivers?

Many hospice organizations, cancer support networks, and disease-specific foundations offer financial aid, equipment, transportation support, or respite grants. Ask your palliative team or social worker for guidance—they often have a directory of local and national resources.

Can I die at home—and what does that actually involve?

Yes, and for many, it’s the preferred setting. Dying at home typically involves home hospice services: regular nurse visits, 24/7 on-call support, medications delivered to your door, and often a hospital bed or other equipment. It also means a more intimate, less clinical environment—but one where caregivers may need more hands-on involvement.

What if I’m not ready to die—or don’t want to accept it?

Then you’re human. Acceptance isn’t a binary state; it’s not required for dying. Some people come to peace. Others never quite do. What matters is that your fears and hopes are heard, your symptoms are managed, and your dignity is preserved. You don’t have to “feel ready” to be cared for well.

Closing Thoughts

There is no perfect way to die—just as there is no perfect way to live. But there are ways to meet the end of life that feel less like collapse and more like coherence. That’s what the terminal cancer couloir is really about: not the frantic final miles of a race, but a narrowing path that demands clarity, courage, and care.

By now, you’ve traveled with us through the full spectrum of what this journey entails. The medical. The emotional. The existential. The structural. You’ve seen that terminal cancer is not just a diagnosis—it’s a terrain. One that requires orientation, language, support systems, and—perhaps most of all—permission. Permission to feel all of it. Permission to choose. Permission to not always be okay.

Whether you’re the one walking the couloir or you’re accompanying someone who is, know this: there are no gold medals for stoicism. You do not have to be inspirational. You only have to be human.

We don’t get to choose the fact of death, but we can influence the way it unfolds. With the right care, the right conversations, and the right companions, the end of life can be more than just loss. It can be a passage full of memory, presence, and even—against all odds—beauty.

Thank you for reading. May this guide offer more than information. May it offer a sense of steadiness, of language, of knowing you are not alone.