Stage 4 Appendix Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide

- What Is Stage 4 Appendix Cancer?

- Signs and Symptoms in Stage 4

- Diagnostic Workup and Staging Procedures

- Treatment Approaches in Advanced Disease

- Prognosis and Factors Affecting Survival

- Histological Subtypes and Clinical Implications

- Systemic Complications and Disease Burden

- Psychological Impact and Emotional Resilience

- Managing Pain, Nausea, and Digestive Symptoms

- Terminal Phase and Spiritual Considerations

- When to Euthanize: Ethical and Clinical Reflections

- Communication and End-of-Life Planning

- The Role of Family, Caregivers, and Emotional Anchors

- Clinical Trials and Experimental Therapies

- Common Missteps and Missed Opportunities

- Reframing the Meaning of Survival

- FAQ

What Is Stage 4 Appendix Cancer?

Stage 4 appendix cancer is the most advanced form of malignancy originating in the appendix, defined by the spread of cancer cells beyond the organ into distant regions of the body. Common metastatic sites include the peritoneal lining, liver, ovaries, and sometimes the lungs. This stage indicates that the disease is no longer confined to a local or regional area, making curative treatment less likely but not always impossible.

Appendiceal cancer itself is extremely rare, accounting for less than 1% of all gastrointestinal cancers. It is typically classified by histological subtype: mucinous adenocarcinoma, non-mucinous adenocarcinoma, goblet cell carcinoma, and signet ring cell carcinoma — each with unique behaviors and response profiles. In Stage 4, these distinctions still matter, but the focus often shifts toward systemic control and quality of life.

As with many advanced cancers, including nasal cancer in dogs, this diagnosis demands a balance between aggressive treatment options and realistic outcome expectations. The goal is to maintain quality of life while extending survival when possible.

Signs and Symptoms in Stage 4

By the time appendix cancer reaches Stage 4, symptoms are usually more pronounced and less ambiguous than in earlier stages. The most common presentation includes persistent abdominal bloating, cramping, pain, and a noticeable increase in abdominal girth due to peritoneal carcinomatosis or mucinous ascites (also known as pseudomyxoma peritonei). In women, the disease may be misdiagnosed as ovarian cancer because of pelvic spread.

Other symptoms may include:

- Chronic fatigue and weakness

- Sudden changes in bowel habits (diarrhea or constipation)

- Nausea or vomiting due to partial bowel obstruction

- Weight loss and poor appetite

- Fluid buildup in the abdomen, leading to breathing difficulty

In cases of liver metastasis, jaundice or abnormal liver function tests may develop. Blood clots and anemia are also potential complications in Stage 4, either due to the cancer itself or side effects from treatment.

Early recognition of these signs is critical. While most cases are caught at a later stage, persistent symptoms that mimic irritable bowel syndrome or gynecologic disorders should prompt further imaging and diagnostic workup. In hindsight, many patients later realize that their early symptoms were subtle but progressive.

Diagnostic Workup and Staging Procedures

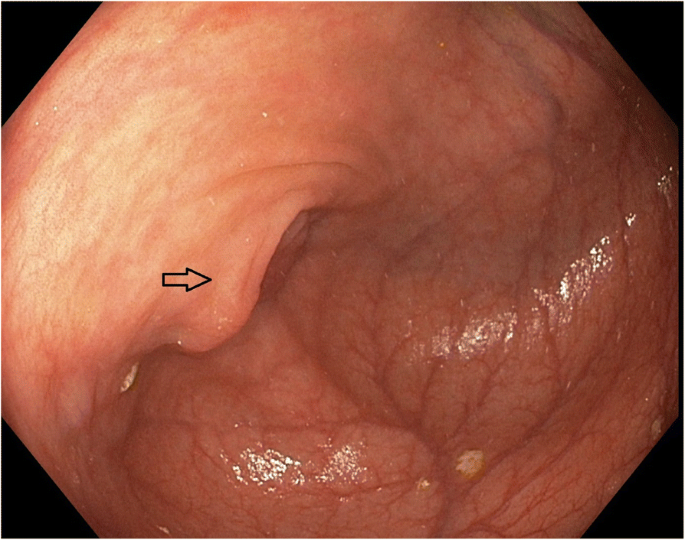

The diagnostic approach to Stage 4 appendix cancer begins with a comprehensive history and physical exam, followed by targeted imaging. CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast are the primary tools to assess tumor burden and the extent of peritoneal involvement. MRI may be used to evaluate liver metastases or subtle mucinous spread, while PET scans can help detect distant organ involvement.

In women, transvaginal ultrasound is often performed to differentiate ovarian spread from primary gynecologic malignancies. Colonoscopy may be necessary if there’s suspicion of synchronous colorectal tumors.

A definitive diagnosis is obtained through biopsy — often during surgery or image-guided aspiration — and confirmed by histopathological analysis. Immunohistochemical staining and genomic profiling are increasingly used to classify subtypes and identify molecular targets for therapy.

Staging is determined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system:

- T: tumor depth and invasion

- N: regional lymph node involvement

- M: distant metastasis

At Stage 4, the “M1” category is fulfilled, signifying at least one site of distant spread. Prognosis and treatment depend heavily on whether the disease is mucin-producing and whether cytoreduction is technically possible.

Treatment Approaches in Advanced Disease

There is no universal protocol for treating Stage 4 appendix cancer; management is highly individualized. However, three main categories guide most treatment plans: cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy), systemic chemotherapy, and palliative care.

Cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC remain the most promising for long-term control in selected patients, especially those with peritoneal-only disease and good functional status. During this operation, visible tumor masses are removed surgically, and heated chemotherapy is infused into the abdominal cavity to destroy microscopic residual cells.

Systemic chemotherapy, often using regimens similar to those for colorectal cancer (e.g., FOLFOX or FOLFIRI), is employed when HIPEC is not possible or as adjunctive therapy. Molecular profiling may reveal targets like KRAS, GNAS, or BRAF mutations that guide the use of targeted agents.

Palliative care becomes increasingly important in cases with widespread metastases, poor surgical candidates, or progressive symptoms despite treatment. This includes pain management, nutritional support, and gastrointestinal symptom relief — all focused on maintaining dignity and comfort.

Prognosis and Factors Affecting Survival

The prognosis in Stage 4 appendix cancer varies widely and depends on tumor subtype, the extent of peritoneal disease, patient performance status, and response to treatment. For example, patients with low-grade mucinous tumors (disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis) may survive for years with aggressive cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC. In contrast, those with high-grade carcinomatosis or signet ring cell histology generally face a poorer outcome.

Age, comorbid conditions, and nutritional status also influence outcomes. Patients with strong baseline function and good response to chemotherapy may achieve meaningful extensions of survival, sometimes reaching two to five years post-diagnosis with sustained multidisciplinary care. However, the median survival for high-grade Stage 4 cases typically ranges from 12 to 20 months.

Importantly, survival data should be contextualized. While statistics provide a framework, they do not predict individual cases. Some patients exceed expectations significantly, especially when managed at specialized centers with experience in rare peritoneal cancers.

Histological Subtypes and Clinical Implications

| Histological Subtype | Behavior | Common Spread Pattern | Prognosis | Comments |

| Low-Grade Mucinous Adenocarcinoma | Indolent, mucin-producing | Peritoneal only | Favorable with HIPEC | Common in pseudomyxoma peritonei |

| High-Grade Mucinous Adenocarcinoma | Aggressive with mucinous | Peritoneum and liver | Intermediate | May respond to surgery + chemo |

| Non-Mucinous Adenocarcinoma | Infiltrative, epithelial | Lymph nodes, liver | Poorer | Treat as colorectal-type cancer |

| Goblet Cell Carcinoma | Neuroendocrine features | Peritoneum, lymph nodes | Variable | Often treated with combo protocols |

| Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma | Highly aggressive | Diffuse spread, early mets | Very poor | Rare, usually advanced at detection |

This classification guides not only prognosis but also surgical planning, chemotherapy sensitivity, and trial eligibility. Subtype-specific management improves survival odds and reduces overtreatment in patients unlikely to benefit from intensive regimens.

Systemic Complications and Disease Burden

Beyond local tumor effects, Stage 4 appendix cancer often exerts systemic stress on multiple organs. One of the most common complications is malignant ascites, in which cancer cells trigger excess fluid buildup, leading to severe abdominal distention, reduced appetite, and impaired breathing. This often requires repeated paracentesis or peritoneal catheter placement.

Bowel obstruction is another frequent issue, especially with mucin-producing tumors. As intestines become compressed or encased by tumor or mucin, patients experience nausea, vomiting, and painful cramping. Surgical intervention may be necessary, although it is not always feasible in advanced cases.

Cachexia — a wasting syndrome marked by profound weight loss and muscle atrophy — also affects many Stage 4 patients, often unresponsive to nutrition alone. Managing fatigue, anemia, and electrolyte disturbances becomes a daily challenge for care teams.

These complications can parallel patterns seen in advanced cancers located in sensitive areas. For instance, patients with invasive tumors like lower eyelid cancer may face similarly complex decisions about balancing intervention and maintaining dignity.

Psychological Impact and Emotional Resilience

The emotional toll of a Stage 4 diagnosis cannot be overstated. Patients often feel overwhelmed by the gravity of their condition, the complexity of treatment options, and the unpredictability of symptoms. Anxiety, depression, and fear of loss of autonomy are common, and these emotional responses may intensify during treatment transitions or hospitalizations.

Families, too, face high levels of stress. Caregiver fatigue is real, especially when balancing work, emotional support, and medical coordination. In some cases, family members are the primary advocates during appointments and the front-line responders to emergencies.

Supportive mental health care, including counseling, mindfulness techniques, and group therapy, significantly improves patients’ coping skills. Even small interventions — a weekly check-in with a counselor, spiritual support, or guided journaling — can help patients reframe their experience and reclaim some sense of control.

Clinical teams should initiate conversations about emotional needs as early as possible, not just near the end of life. Proactive psychological care is as critical as physical treatment in preserving dignity and extending peace of mind.

Managing Pain, Nausea, and Digestive Symptoms

Symptom management is one of the pillars of care for patients with Stage 4 appendix cancer. As tumors grow and invade abdominal organs or produce excess mucin, they exert pressure on intestines, blood vessels, and nerves — all of which can create significant discomfort.

Pain may stem from peritoneal inflammation, nerve compression, or surgical complications. It is typically managed using a tiered approach: acetaminophen or NSAIDs for mild pain, progressing to opioids such as morphine or fentanyl patches for moderate to severe pain. For neuropathic discomfort, gabapentinoids or antidepressants may also be prescribed.

Nausea and vomiting are frequently triggered by bowel obstruction, chemotherapy, or mucin overload. Antiemetics like ondansetron, metoclopramide, or olanzapine can help control these symptoms. In cases of intractable nausea, palliative decompression (via nasogastric or PEG tube) may be considered.

Constipation and diarrhea often alternate due to partial obstruction or chemotherapy side effects. Bowel regimens are tailored individually using laxatives, antispasmodics, or stool softeners.

Proactive symptom management — initiated early — not only preserves physical function but prevents emergency hospitalizations that often compound distress in terminal patients.

Terminal Phase and Spiritual Considerations

As Stage 4 appendix cancer progresses beyond the reach of effective disease-modifying treatment, the clinical focus shifts toward terminal care. This phase is characterized by progressive frailty, fatigue, appetite loss, and growing dependence on caregivers.

At this point, medical priorities include controlling discomfort, maintaining dignity, and supporting the patient’s emotional and spiritual needs. Hospice services — whether at home or inpatient — provide critical resources including 24/7 nursing, pain control, social work, and chaplaincy.

Patients may also explore legacy work, writing letters to family, recording messages, or sharing memories. These small acts often bring peace and closure, helping patients feel that they are leaving a mark beyond their diagnosis.

Interestingly, the emotional parallels between terminal human care and animal oncology — such as nasal cancer in dogs, where owners must also make palliative decisions under stress — highlight the universal weight of saying goodbye, whether for a pet or a loved one.

When to Euthanize: Ethical and Clinical Reflections

Deciding when to stop active treatment and consider assisted dying — where legally available — or purely comfort-focused care is among the most difficult conversations for any family. In many cases, the question is not when death will occur, but how — and how much suffering is acceptable.

Signs that a patient may be nearing the end of their tolerable journey include:

- Constant, unrelieved pain despite escalated medication

- Persistent vomiting with no nutritional intake

- Complete bowel obstruction without surgical option

- Delirium or altered mental status from liver failure or metastasis

- Withdrawal from interaction, apathy, or visible distress

- Recurrent hospitalizations with diminishing returns

In regions where euthanasia is legally permitted, it may be considered if the patient, in full capacity, requests a dignified end to a painful and irreversible process. Elsewhere, withdrawal of life-prolonging interventions and initiation of terminal sedation may be options.

These decisions must be guided by patient values, religious beliefs, medical input, and — above all — a shared commitment to dignity. As physicians, our goal is not to extend suffering but to accompany the patient with honesty, comfort, and respect.

Communication and End-of-Life Planning

Open, compassionate communication is essential at all stages of terminal illness — but especially as end-of-life approaches. Families and care teams should regularly revisit goals, treatment burdens, and expectations to ensure alignment between medical actions and patient wishes.

Advance care planning is central. This includes creating advance directives, appointing healthcare proxies, and deciding on resuscitation preferences. For many, having these documents in place provides clarity and peace of mind, both for themselves and their families.

Clinicians should also discuss the dying process openly: what to expect, what symptoms will appear, and what can be done to ensure comfort. Families who understand what’s ahead often report less regret and emotional trauma after death.

This conversation mirrors those held in geriatric oncology and palliative specialties worldwide — and even in complex cases like pi-rads 4 prostate cancer survival rate, where treatment limits must be weighed compassionately.

The Role of Family, Caregivers, and Emotional Anchors

Family members often become the central figures in the care of a loved one with Stage 4 appendix cancer. They provide not only physical support — assisting with medication, hygiene, nutrition, and mobility — but also serve as emotional anchors, helping the patient navigate fear, grief, and difficult decisions.

Caregiving at this stage is both rewarding and exhausting. Caregivers may feel helpless watching symptoms progress, or isolated as they focus their time and energy entirely on one person. It’s vital to recognize and support the emotional well-being of the family as well. Psychological counseling, caregiver respite services, and family therapy sessions can be incredibly valuable.

Effective communication within the family is also critical. Aligning on care goals, sharing responsibilities, and preparing for the end of life together can prevent conflict and strengthen emotional bonds in the final weeks.

Clinical Trials and Experimental Therapies

For some patients with Stage 4 appendix cancer, especially those who have exhausted standard treatment options, participation in a clinical trial can offer renewed hope. Trials may involve novel chemotherapy combinations, targeted therapies, immunotherapy agents, or enhanced HIPEC protocols.

Enrollment eligibility depends on several factors: tumor subtype, molecular profile, performance status, and previous treatments. Many trials are conducted at major cancer centers specializing in gastrointestinal or peritoneal surface malignancies.

Before joining a trial, patients and families should understand:

- The phase of the study (I, II, or III)

- The potential risks and benefits

- Whether the treatment is randomized

- Any impact on quality of life

While not every experimental therapy leads to extended survival, participating in research can offer patients a sense of purpose, knowing they are contributing to better care for others in the future.

Common Missteps and Missed Opportunities

In the journey with Stage 4 appendix cancer, certain mistakes can compromise both longevity and quality of life. One frequent issue is treatment delay — often due to misdiagnosis, underestimating symptoms, or systemic barriers to imaging and specialist referral. By the time a definitive diagnosis is made, disease progression may already limit treatment options.

Another pitfall is over-treatment in the terminal phase, where chemotherapy is continued despite declining function, leading to hospitalizations, side effects, and diminished dignity in the final months.

Equally, under-treatment of symptoms — such as pain, breathlessness, and anxiety — can create needless suffering. This happens when palliative care is introduced too late or not offered at all.

Clear communication, timely palliative integration, and realistic goal-setting are essential to avoiding these outcomes. Empowered patients and proactive care teams reduce regret and preserve comfort.

Reframing the Meaning of Survival

Stage 4 appendix cancer represents a turning point in a person’s life — one where numbers, scans, and surgeries become deeply personal. It forces patients and families to confront mortality, redefine priorities, and choose how to live with what time remains.

Survival, in this context, is not merely about duration. It’s about how we use that time: preserving dignity, maintaining connection, and avoiding unnecessary suffering. It’s about the courage to say “enough” when the burden of treatment outweighs the benefit — and the strength to make that choice without shame.

Incorporating palliative care, spiritual guidance, and honest communication allows patients to reclaim their voice and make decisions aligned with their deepest values.

The end of a cancer journey does not have to be a defeat. It can be a transition, guided by compassion, clarity, and the unwavering presence of those we love.

FAQ

What is Stage 4 appendix cancer?

Stage 4 appendix cancer means the disease has spread beyond the appendix to distant organs or the peritoneal cavity. It is the most advanced form of this rare cancer and typically requires systemic treatment and palliative support. It often involves widespread mucinous deposits, liver metastases, or lymphatic spread.

How is Stage 4 appendix cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis is made using CT scans, MRIs, biopsies, and in some cases, exploratory surgery. A tissue sample confirms the type of tumor, and imaging helps determine the extent of disease spread. Blood tests may also reveal tumor markers or abnormalities in liver function.

Is Stage 4 appendix cancer curable?

In most cases, Stage 4 appendix cancer is not considered curable, but some patients achieve long-term survival with aggressive surgery and HIPEC. The main goal becomes controlling the disease, alleviating symptoms, and extending life while maintaining quality of life.

What are the treatment options for Stage 4 appendix cancer?

Treatment may include cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC, systemic chemotherapy, targeted therapies based on molecular profiling, and palliative care. The choice depends on tumor type, extent of spread, and overall patient health.

What is HIPEC and how does it help?

HIPEC (hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy) involves delivering heated chemotherapy directly into the abdominal cavity after surgical tumor removal. It’s particularly effective for mucinous tumors and may improve survival when combined with complete cytoreduction.

How long can someone live with Stage 4 appendix cancer?

Survival varies widely. Some patients with low-grade tumors may live several years after surgery and HIPEC. Others with aggressive or high-grade disease may have a median survival of 12–20 months. Each case is unique.

What is pseudomyxoma peritonei and how is it related?

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a condition where mucin-producing appendix tumors spread gelatinous material throughout the abdominal cavity. It’s often associated with low-grade mucinous tumors and may respond well to HIPEC if caught early.

Is chemotherapy always necessary?

Chemotherapy is often used when surgery isn’t possible or as an adjunct to reduce recurrence risk. Some patients with low-grade, slow-growing tumors may avoid it, while those with aggressive histology typically require systemic treatment.

Can appendix cancer spread to other organs?

Yes. Stage 4 disease may spread to the liver, lungs, ovaries, or bones. This metastasis influences prognosis and limits surgical options, requiring more comprehensive systemic therapy and supportive care.

What are the symptoms near the end of life?

Common terminal symptoms include abdominal pain, fluid accumulation, bowel obstruction, fatigue, poor appetite, and progressive weight loss. Emotional withdrawal and increased sleep may also indicate the body is shutting down.

When should we consider stopping treatment?

Treatment should be reconsidered when side effects outweigh benefits, the patient expresses a desire to focus on comfort, or there is clear evidence that therapies are no longer effective. This decision should involve the patient, family, and palliative team.

What is the role of palliative care in Stage 4 cancer?

Palliative care improves quality of life by managing symptoms like pain, nausea, breathlessness, and fatigue. It also provides emotional, psychological, and spiritual support for both the patient and their loved ones.

Can patients with Stage 4 appendix cancer participate in clinical trials?

Yes. Clinical trials often include patients with rare cancers. Depending on the molecular profile of the tumor and previous treatments, trials may offer access to cutting-edge therapies and contribute to research for future patients.

What should I discuss with my doctor after a Stage 4 diagnosis?

You should talk about your treatment goals, options, prognosis, quality-of-life priorities, advance care planning, and eligibility for clinical trials. These conversations help guide care according to your values and preferences.

Is it possible to have a peaceful end-of-life experience with this diagnosis?

Absolutely. With proper palliative care, early communication, and emotional support, patients can experience a dignified, symptom-controlled, and meaningful end-of-life journey surrounded by loved ones.