Spinal Cancer in Dogs: A Comprehensive Guide

- Understanding Spinal Cancer in Dogs

- Common Types of Spinal Tumors in Dogs

- Recognizing Symptoms of Spinal Cancer

- Diagnostic Approaches to Spinal Tumors

- Treatment Options for Spinal Cancer in Dogs

- Surgical Intervention: When and How It’s Used

- Prognosis and Survival Rates

- Recovery and Rehabilitation After Treatment

- Managing Pain and Neurological Symptoms

- Long-Term Monitoring and Relapse Prevention

- Lifestyle Modifications and Supportive Care at Home

- Emotional Impact on Pet Owners and Decision-Making

- Alternative and Integrative Therapies

- Differences Between Spinal Cancer and Other Neurological Disorders

- Spinal Tumors in Different Dog Breeds and Ages

- End-of-Life Care and Euthanasia Decisions

- FAQ

Understanding Spinal Cancer in Dogs

Spinal cancer in dogs encompasses a range of neoplastic conditions affecting the spinal cord, vertebrae, or surrounding tissues. These tumors can be primary, originating in the spine, or secondary, resulting from metastasis. Primary spinal tumors, such as meningiomas, gliomas, and nerve sheath tumors, are relatively rare but can have significant neurological implications. Secondary tumors often arise from cancers like hemangiosarcoma or lymphoma spreading to the spine.

The classification of spinal tumors is based on their location: extradural (outside the dura mater), intradural-extramedullary (inside the dura but outside the spinal cord), and intramedullary (within the spinal cord). Extradural tumors are the most common, accounting for approximately 50% of spinal tumors in dogs. Intradural-extramedullary tumors represent about 30%, while intramedullary tumors are less common, comprising around 15% .

Understanding the type and location of the tumor is crucial for determining the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Early detection and intervention can significantly impact the prognosis and quality of life for affected dogs.

Common Types of Spinal Tumors in Dogs

Several types of tumors can affect the canine spine, each with distinct characteristics and implications.

Extradural Tumors: These tumors are located outside the dura mater and often involve the vertebral bones. Common extradural tumors include osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and fibrosarcoma. These tumors can cause bone destruction and spinal instability, leading to pain and neurological deficits.

Intradural-Extramedullary Tumors: Situated within the dura mater but outside the spinal cord, these tumors often compress the spinal cord, leading to neurological signs. Meningiomas and nerve sheath tumors are prevalent in this category. Meningiomas are typically slow-growing and may be amenable to surgical removal.

Intramedullary Tumors: These tumors arise within the spinal cord itself and are less common. Examples include astrocytomas and ependymomas. Due to their location, surgical intervention is challenging, and treatment often involves radiation therapy.

Metastatic Tumors: Secondary tumors result from the spread of cancer from other body parts to the spine. Common primary cancers that metastasize to the spine include hemangiosarcoma and lymphoma. These tumors can affect any part of the spine and often present with rapid onset of neurological signs.

Identifying the specific type of tumor is essential for developing an effective treatment plan and providing an accurate prognosis.

Recognizing Symptoms of Spinal Cancer

Early recognition of spinal cancer symptoms in dogs is vital for prompt diagnosis and treatment. Symptoms often correlate with the tumor’s location and the extent of spinal cord compression.

Pain: One of the most common signs, pain may manifest as vocalization, reluctance to move, or sensitivity when touched along the spine.

Neurological Deficits: Depending on the tumor’s location, dogs may exhibit weakness, incoordination, or paralysis in one or more limbs. For instance, tumors in the cervical spine can affect all four limbs, while thoracolumbar tumors may impact the hind limbs.

Changes in Gait: Dogs may develop an abnormal gait, such as a wobbly or unsteady walk, due to impaired nerve signaling.

Incontinence: Loss of bladder or bowel control can occur if the tumor affects nerves responsible for these functions.

Behavioral Changes: Some dogs may become withdrawn, less active, or show signs of depression due to chronic pain or discomfort.

These symptoms can develop gradually or appear suddenly, depending on the tumor’s nature and growth rate. Any of these signs warrant immediate veterinary evaluation.

Diagnostic Approaches to Spinal Tumors

Accurate diagnosis of spinal tumors in dogs involves a combination of clinical evaluation and advanced imaging techniques.

Neurological Examination: A thorough neurological exam helps localize the lesion within the spinal cord and assess the severity of deficits.

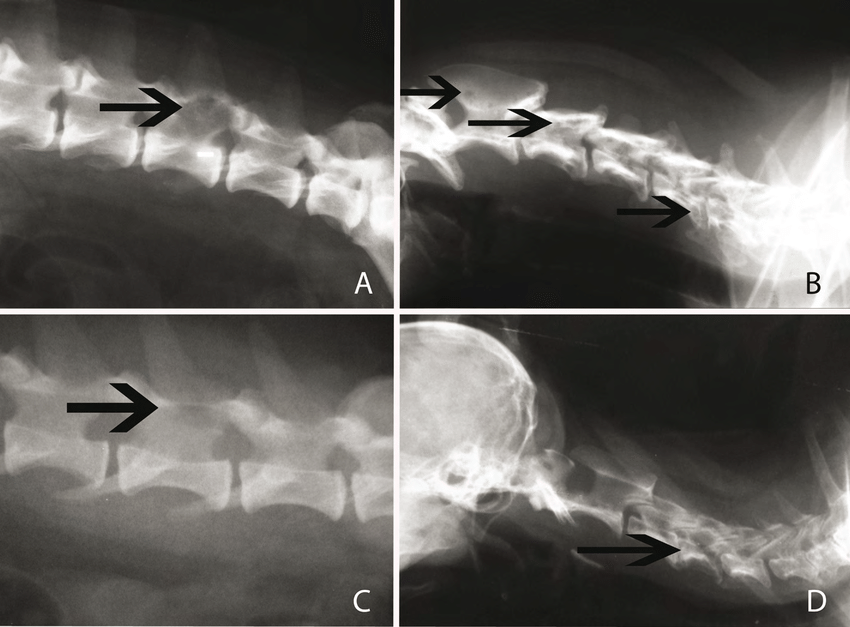

Radiography (X-rays): While X-rays can reveal bone abnormalities, they have limited utility in detecting soft tissue tumors or intramedullary lesions.

Myelography: This imaging technique involves injecting a contrast agent into the spinal canal to visualize the spinal cord and detect compressive lesions.

Computed Tomography (CT): CT scans provide detailed images of the vertebral bones and are useful for identifying bony tumors or assessing bone involvement.

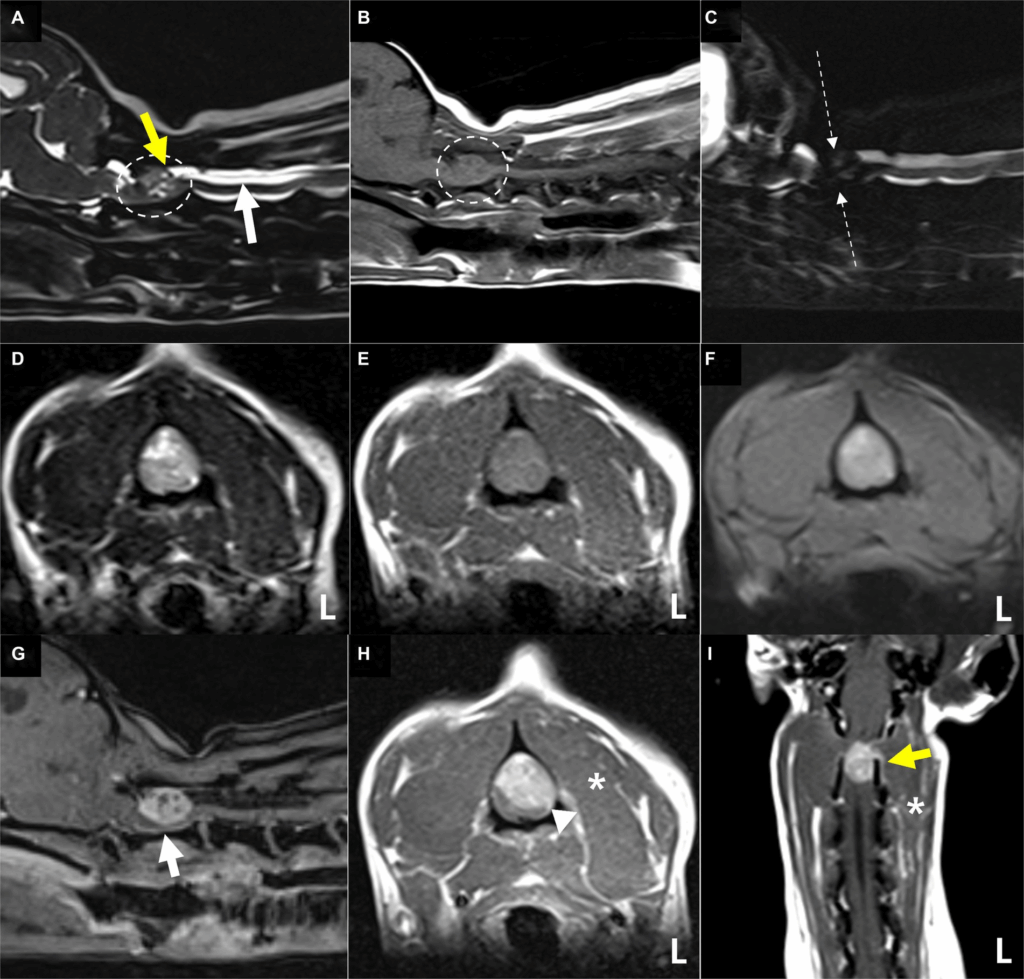

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is the gold standard for evaluating spinal cord tumors, offering superior soft tissue contrast and detailed images of the spinal cord and surrounding structures.

Biopsy: Obtaining a tissue sample through surgical or needle biopsy allows for histopathological examination, confirming the tumor type and guiding treatment decisions.

Timely and accurate diagnosis is crucial for initiating appropriate therapy and improving the dog’s quality of life.

Treatment Options for Spinal Cancer in Dogs

Treatment of spinal cancer in dogs depends on the type, location, and progression of the tumor, as well as the dog’s overall health. A multidisciplinary approach is often required to manage symptoms and extend quality of life. Surgery is commonly recommended when the tumor is accessible and operable, particularly for extradural or intradural-extramedullary tumors. The goal of surgery is decompression of the spinal cord and, when possible, full excision of the mass.

Radiation therapy is frequently used, especially for intramedullary or inoperable tumors. It helps reduce tumor size and alleviate pressure on the spinal cord. Stereotactic radiation, which delivers highly focused doses, is becoming increasingly available in veterinary oncology.

Chemotherapy may be effective in cases of lymphoma or metastatic tumors but is generally less successful with primary spinal cancers. Pain management, corticosteroids, and physical therapy are essential components of palliative care, particularly when curative treatment is not feasible.

Surgical Intervention: When and How It’s Used

Surgery is the most definitive treatment for many types of spinal tumors, but it carries inherent risks. Decisions about surgery must weigh tumor location, likelihood of complete excision, potential neurologic recovery, and the dog’s age and systemic health.

Extradural tumors that affect vertebrae or compress the spinal cord from outside are more accessible for removal. These surgeries often involve laminectomy or vertebral stabilization. Intradural-extramedullary tumors may also be removed surgically, though success depends on their exact position and adherence to nerve structures.

Intramedullary tumors are rarely resected due to the risk of permanent spinal cord damage. In those cases, debulking or biopsy may be performed to facilitate adjunctive therapy. Surgical success is highest when the tumor is localized and slow-growing, with careful post-operative care including pain control, physiotherapy, and bladder management.

Prognosis and Survival Rates

Prognosis varies widely depending on tumor type, stage at diagnosis, response to therapy, and access to advanced treatment options. In general, extradural tumors such as osteosarcomas have a guarded prognosis due to their aggressive nature and tendency to metastasize. Median survival times for dogs with surgical removal followed by radiation may range from 6 to 18 months.

Dogs with meningiomas, particularly when caught early and completely excised, can have favorable outcomes. In contrast, intramedullary tumors often have poor prognoses because of the challenges in surgical access and limited response to chemotherapy.

Palliative care, when curative treatment is not viable, can still provide significant relief and extend quality of life by several months. Owners should be prepared for progressive mobility decline and increasing care needs over time.

Recovery and Rehabilitation After Treatment

Post-treatment recovery for dogs with spinal cancer is highly individual and depends on the extent of neurological damage and the invasiveness of the procedure. Recovery protocols focus on pain management, wound care, and rehabilitation to restore strength and coordination.

Dogs that undergo surgery often require crate rest and limited activity for several weeks. Supportive devices such as slings or harnesses may be needed to assist with mobility. Rehabilitation therapy, including hydrotherapy, laser therapy, and assisted walking, can significantly improve neurological outcomes.

Owners play a critical role during recovery, ensuring the dog remains clean, receives medications on schedule, and maintains good nutrition and hydration. Recheck appointments are essential to monitor healing, assess for tumor recurrence, and adjust supportive care plans as needed.

Managing Pain and Neurological Symptoms

Pain management is a cornerstone of spinal cancer care, whether curative treatment is pursued or not. Dogs with spinal tumors frequently experience chronic pain due to nerve compression or direct invasion of the vertebrae. Managing this pain effectively not only improves quality of life but also helps restore mobility and emotional well-being.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often prescribed, but they must be used cautiously in dogs with compromised renal function. Opioids like tramadol or fentanyl patches may be introduced for more severe pain. Corticosteroids such as prednisone are frequently used to reduce inflammation and edema around the tumor, which can significantly relieve neurologic symptoms.

Gabapentin is another valuable medication, particularly for managing nerve-related pain. In advanced cases, veterinarians may create a tailored pain control protocol combining multiple drugs. Physical therapy and acupuncture may be used alongside medication to help reduce stiffness and restore some functionality.

Long-Term Monitoring and Relapse Prevention

Ongoing monitoring is essential after the initial treatment of spinal cancer. Even when the tumor has been surgically removed or reduced via radiation, recurrence is possible. Veterinarians typically recommend neurological exams every 1–2 months during the first six months and then every three to six months thereafter.

Periodic imaging — either MRI or CT — may be scheduled to detect any new growths or evaluate changes in the surgical site. Blood work helps monitor organ function, especially when medications like NSAIDs or chemotherapy agents are used long term.

Relapse prevention focuses on early detection and proactive management of any subtle signs of neurologic regression. Owners should be educated to report symptoms such as stiffness, dragging of limbs, or loss of bladder control as soon as they appear. Adjustments to therapy, including the addition of corticosteroids or initiation of another treatment round, are often based on these observations.

Lifestyle Modifications and Supportive Care at Home

Dogs living with or recovering from spinal cancer benefit greatly from environmental modifications that reduce stress on the spine and prevent injury. Slippery floors should be covered with rugs or mats to improve traction. Ramps are preferable to stairs, especially for dogs with thoracolumbar tumors.

Orthopedic beds or memory foam mattresses help reduce pressure points and joint discomfort. Raised feeding dishes can also assist dogs with neck or spine pain. Harnesses with back-end support are often necessary for dogs with hind limb weakness.

In terms of activity, walks should be short and controlled, avoiding sudden movements or rough terrain. Mental stimulation, gentle interaction, and consistent routines support emotional health. These dogs often thrive with stable, low-stress environments and attentive, patient caregivers who understand the limitations imposed by spinal disease.

Emotional Impact on Pet Owners and Decision-Making

Receiving a diagnosis of spinal cancer in a beloved dog is emotionally overwhelming for most owners. The impact of seeing a once-active pet struggle with mobility or pain creates intense stress, grief, and guilt — even when treatment is underway.

Veterinarians play an important role in guiding families through decision-making. This includes setting realistic expectations, explaining both the benefits and burdens of treatment, and supporting the owner’s emotional journey. Some owners may choose aggressive treatment; others may prioritize comfort and opt for palliative care.

Open communication is essential throughout the process. Regular check-ins, progress updates, and clear answers to evolving concerns help build trust. Many owners find peace in knowing they’ve explored every reasonable option and maintained compassion for their dog’s comfort and dignity.

Alternative and Integrative Therapies

While conventional treatments remain the standard of care, some owners seek complementary approaches to support their dog’s comfort and general wellness. Integrative therapies are not curative but may offer adjunctive benefits, especially in palliative cases.

Acupuncture is increasingly used in veterinary neurology to manage chronic pain and improve nerve function. Some dogs with partial paralysis show improved limb awareness and gait after regular sessions. Herbal supplements like turmeric (curcumin) or boswellia are sometimes incorporated for their anti-inflammatory properties, though they should always be used under veterinary supervision.

Other integrative options include laser therapy, chiropractic adjustments, and homeopathic remedies. While evidence supporting these methods varies, many practitioners and owners report anecdotal improvements in mobility and comfort. Integrative care should never replace diagnostics or critical interventions but can provide additional support when guided by a professional familiar with spinal oncology.

Differences Between Spinal Cancer and Other Neurological Disorders

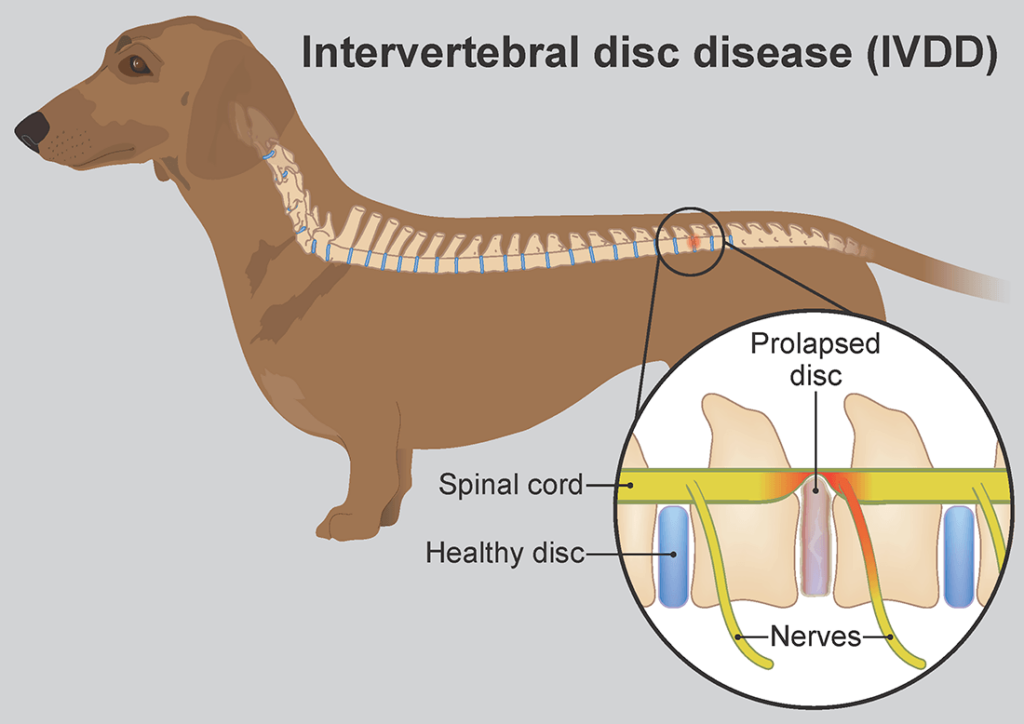

Because many spinal tumors mimic other neurologic conditions, accurate diagnosis is critical. Intervertebral disc disease (IVDD), degenerative myelopathy, and spinal trauma can all present with similar symptoms: weakness, incoordination, pain, or incontinence.

However, key distinctions exist. Spinal cancer often progresses steadily or worsens rapidly without fluctuation. It may cause persistent and deep-seated pain, while conditions like IVDD may have sudden onset but stabilize with rest or medical therapy. Unlike degenerative myelopathy, spinal cancer often presents asymmetrically or causes muscle wasting.

Imaging and biopsy are the only definitive ways to differentiate spinal tumors from other pathologies. Veterinarians rely on neurologic exams, history, and clinical signs to guide initial suspicion but always confirm with advanced diagnostics before initiating therapy.

Spinal Tumors in Different Dog Breeds and Ages

Spinal cancer can occur in any dog, but certain breeds and ages show increased susceptibility. Middle-aged to senior dogs are most commonly affected, with many cases diagnosed between 7 and 12 years of age. Large and giant breeds, such as German Shepherds, Boxers, and Golden Retrievers, are more frequently diagnosed with vertebral tumors like osteosarcomas.

Meningiomas and nerve sheath tumors are more common in older dogs and tend to appear in breeds like Shelties, Dobermans, and mixed breeds. Lymphoma, a hematopoietic cancer that may involve the spine, can occur in dogs of any breed or age but has been documented more frequently in Retrievers and Labradors.

Age, genetics, hormonal status, and exposure to environmental carcinogens may all influence cancer risk. While spinal tumors are not considered highly breed-specific, awareness of these predispositions can help with early recognition in at-risk dogs.

End-of-Life Care and Euthanasia Decisions

Despite the best efforts, some dogs with spinal cancer will reach a point where curative or even palliative treatments no longer maintain their quality of life. In these cases, compassionate end-of-life care becomes the priority. Signs that may prompt these discussions include unmanageable pain, total loss of mobility, incontinence, anorexia, or severe behavioral changes.

Veterinarians can assist with pain control, hospice-style support, and objective assessments of suffering using quality-of-life scales. When a dog can no longer enjoy its daily routine or interact meaningfully with its family, euthanasia may be considered the most humane option.

These decisions are deeply personal, and every situation is unique. Owners should be supported emotionally and informed medically, with time to ask questions and express concerns. When handled with empathy and preparation, end-of-life care can offer peace and dignity for both the dog and its family.

FAQ

What is spinal cancer in dogs?

Spinal cancer in dogs refers to the development of malignant or benign tumors that affect the spine, spinal cord, or surrounding structures. These tumors may originate in the spine (primary) or spread there from other parts of the body (metastatic), often causing pain and neurological symptoms.

What are the common types of spinal tumors in dogs?

The most common types include extradural tumors like osteosarcoma, intradural-extramedullary tumors such as meningioma, and intramedullary tumors like glioma. Secondary tumors from cancers like lymphoma and hemangiosarcoma can also metastasize to the spine.

What are the first signs of spinal cancer in dogs?

Initial symptoms often include back pain, reluctance to move, limping, or stiffness. As the tumor progresses, dogs may develop neurological issues such as hind limb weakness, incoordination, or even partial paralysis, depending on the tumor’s location.

How is spinal cancer in dogs diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves a neurological exam, imaging such as MRI or CT, and sometimes a biopsy. These tests help determine the tumor’s location, type, and extent of spinal cord compression, which are critical for treatment planning.

Can spinal cancer be cured in dogs?

Some cases, particularly those involving slow-growing and surgically accessible tumors, may be cured or well-managed for extended periods. However, many spinal cancers are difficult to fully eliminate, and treatment often focuses on symptom control and quality of life.

What are the treatment options for dogs with spinal cancer?

Treatment may include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and palliative care. The choice depends on the tumor type, size, and location, as well as the dog’s overall health and how advanced the disease is at diagnosis.

How successful is surgery for spinal tumors in dogs?

Surgery can be highly effective for certain tumor types like meningiomas or nerve sheath tumors, especially when caught early. However, not all tumors are operable, and outcomes vary depending on location and how much of the tumor can be safely removed.

What is the prognosis for dogs with spinal cancer?

Prognosis ranges from several months to over a year, depending on the tumor type, treatment success, and how early it was diagnosed. Some dogs live comfortably with supportive care, while others may experience rapid decline without intervention.

Can dogs recover mobility after treatment?

Yes, some dogs regain partial or even full mobility, especially if treatment relieves spinal cord pressure and rehabilitation is consistent. Recovery often involves physical therapy, pain management, and home support.

Is spinal cancer more common in certain breeds?

While spinal tumors can affect any dog, large breeds like German Shepherds and Golden Retrievers may be more prone to bone cancers. Older dogs are generally at higher risk, but spinal lymphoma can also appear in younger dogs.

What are the side effects of treatment?

Side effects may include pain from surgery, fatigue from radiation, and gastrointestinal issues from chemotherapy. Long-term steroid use can cause increased thirst, appetite, or muscle loss. Close monitoring and veterinary follow-up are essential.

How can I make my home more comfortable for a dog with spinal cancer?

Provide soft bedding, ramps instead of stairs, and non-slip flooring. Limit jumping or rough activity and offer support harnesses if mobility is reduced. Keeping the dog in a calm, stable environment helps reduce stress on the spine.

Is it possible to prevent spinal cancer in dogs?

There is no guaranteed way to prevent spinal cancer, but early detection of any neurologic changes and routine checkups can lead to earlier diagnosis. Avoiding exposure to toxins and managing general health may also reduce risk.

What is palliative care for spinal cancer in dogs?

Palliative care focuses on keeping the dog comfortable through pain management, mobility aids, and supportive therapies like acupuncture or massage. It is often chosen when curative treatment is not an option, and it can greatly improve remaining quality of life.

When should euthanasia be considered for dogs with spinal cancer?

Euthanasia may be considered when pain is no longer manageable, the dog loses bladder control or mobility completely, stops eating, or no longer shows interest in surroundings. A quality-of-life assessment with your vet can guide this difficult decision.