Retroperitoneal Cancer: An In-Depth Overview

- Understanding Retroperitoneal Cancer

- Types of Retroperitoneal Tumors

- Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

- Diagnostic Approaches

- Treatment Options: Surgery, Radiation, and Chemotherapy

- Histological Subtypes and Their Clinical Behavior

- Prognosis and Survival Outlook

- Staging and Grading Retroperitoneal Tumors

- Monitoring and Follow-Up After Treatment

- Recurrent and Metastatic Disease

- Quality of Life and Long-Term Outcomes

- Genetic and Molecular Profiling

- Pediatric Retroperitoneal Tumors

- Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Involvement

- Rare and Aggressive Retroperitoneal Malignancies

- Psychological Support and Caregiver Involvement

- FAQ

Understanding Retroperitoneal Cancer

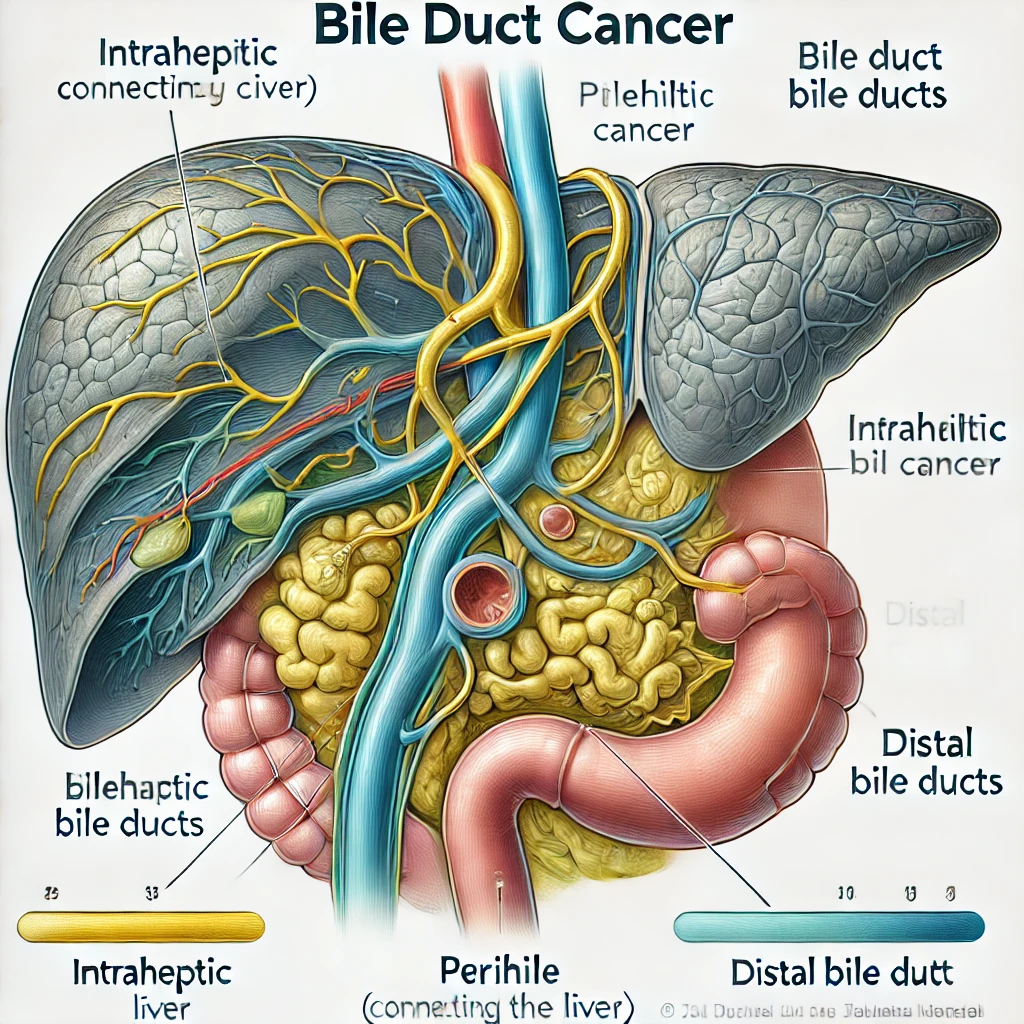

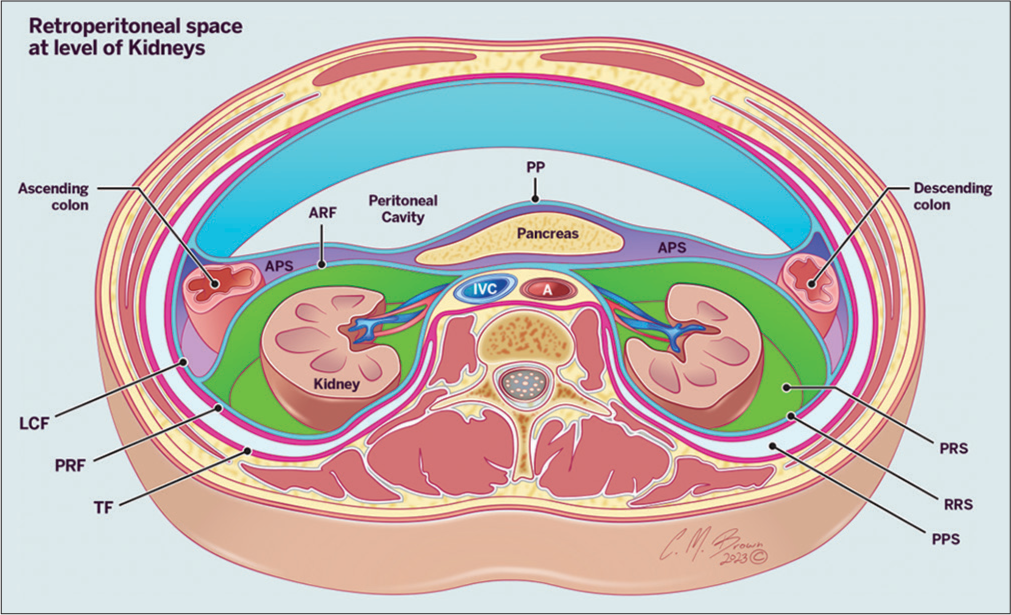

Retroperitoneal cancer refers to a rare group of malignancies that develop in the retroperitoneum—the anatomical space situated behind the peritoneum, which is the lining of the abdominal cavity. This area contains critical structures including the kidneys, pancreas, adrenal glands, aorta, inferior vena cava, lymph nodes, and connective tissues. Because of the retroperitoneum’s depth and the space available for tumor growth without early interference with organ function, cancers in this region can develop silently for a long time.

Most retroperitoneal cancers originate from connective tissues, which is why sarcomas are the predominant type. However, tumors can also arise from the organs within this space or be secondary malignancies (metastases) from cancers elsewhere. The term “retroperitoneal cancer” is not one single disease but a classification based on tumor location, making diagnosis and management particularly complex. Understanding this disease requires recognizing the variety of tissue types that can become malignant and appreciating the subtle signs it can produce before becoming clinically evident.

Types of Retroperitoneal Tumors

Retroperitoneal tumors are broadly classified into benign and malignant types. Among malignant tumors, soft tissue sarcomas dominate. The most common histological subtypes include:

- Liposarcoma – originates from fat cells; often large and slow-growing but may recur.

- Leiomyosarcoma – arises from smooth muscle, including blood vessels; tends to be aggressive.

- Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors – associated with nerve structures and may occur in genetic syndromes like neurofibromatosis type 1.

- Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma – a high-grade tumor with aggressive behavior and poor prognosis.

Other cancers in the retroperitoneal area may include lymphomas (usually non-Hodgkin’s), testicular cancer with metastasis to retroperitoneal nodes, adrenal cortical carcinoma, and secondary cancers spreading from the colon, pancreas, or kidney. Each type has distinct biological behavior, requiring specific diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

It is important to distinguish between these types using histological and molecular analysis after biopsy, as treatment protocols vary greatly depending on tumor origin. For example, a retroperitoneal lymphoma may respond well to chemotherapy, while a sarcoma may require surgery as the primary treatment modality.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

One of the most challenging aspects of retroperitoneal cancer is its silent progression. Due to the expansive space in the retroperitoneal cavity, tumors can grow to a significant size before causing any noticeable symptoms. This makes early detection difficult and often leads to diagnosis at an advanced stage.

The earliest symptoms are often vague and nonspecific. Patients may report a dull, persistent abdominal or flank pain, which can be misattributed to gastrointestinal or musculoskeletal issues. As the tumor enlarges, it may compress adjacent organs or blood vessels, causing a range of symptoms such as:

- Gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, constipation, bloating)

- Weight loss without dieting

- Palpable abdominal mass

- Lower back pain

- Swelling in the legs due to vascular compression

- Early satiety if the stomach is compressed

In rare cases, tumors may rupture or bleed internally, causing acute symptoms. Because such signs are easily mistaken for benign conditions, retroperitoneal cancer is often not considered until imaging reveals a suspicious mass. For this reason, any persistent abdominal symptoms or unexplained weight loss should prompt further investigation.

Diagnostic Approaches

Accurate diagnosis of retroperitoneal cancer is a multistep process that integrates clinical suspicion, imaging studies, and histological evaluation. Initial steps usually begin with physical examination and basic blood tests, but these are often non-revealing unless the tumor has caused metabolic derangements or significant mass effect.

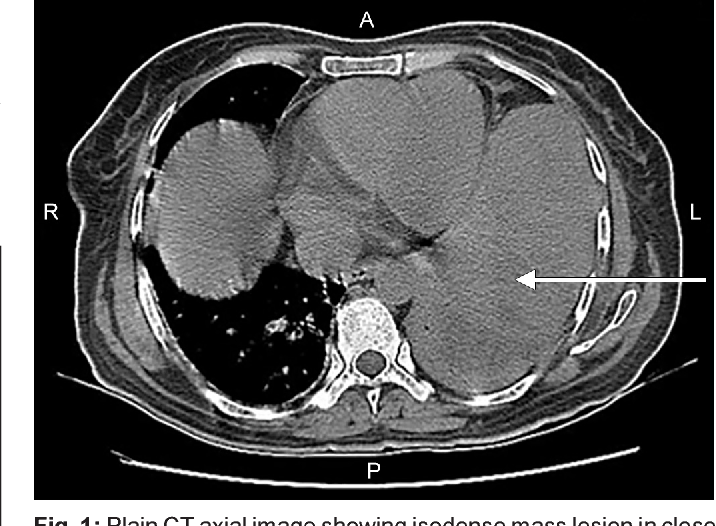

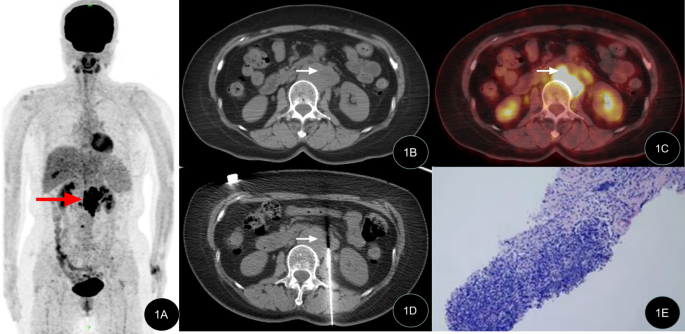

Imaging is the cornerstone of diagnosis. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is typically the first imaging study performed. It helps in visualizing the tumor’s size, margins, involvement of surrounding structures, and presence of metastatic spread. MRI can offer superior soft tissue contrast, especially useful for assessing neurovascular involvement or delineating the tumor from adjacent organs.

Once a mass is confirmed, a percutaneous core needle biopsy is often performed under CT or ultrasound guidance. This provides a tissue sample that is critical for determining the tumor’s type, grade, and molecular characteristics. Histopathological analysis will identify specific markers (e.g., MDM2 amplification in liposarcoma), which can guide therapy.

Additional evaluations may include PET-CT for staging, laboratory tests (LDH, liver function tests), and genetic studies in select cases. Comprehensive diagnostic work-up ensures that the treatment plan is tailored to the tumor’s biology, not just its location.

Treatment Options: Surgery, Radiation, and Chemotherapy

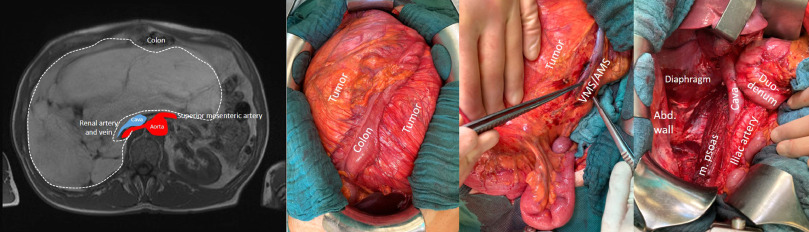

The cornerstone of retroperitoneal cancer treatment is surgical removal, particularly when the tumor is resectable and confined to the retroperitoneum. Surgery often requires a multidisciplinary team due to the proximity of critical organs and vessels. Complete resection with negative margins is the goal, but this can be challenging when tumors encase or compress major structures like the aorta, inferior vena cava, or kidneys. In such cases, surgeons may need to remove and reconstruct adjacent tissues.

Radiation therapy is typically used in conjunction with surgery, especially in high-grade sarcomas. Preoperative radiation may shrink the tumor and reduce the risk of local recurrence. Postoperative radiation is an option when surgical margins are positive or close. However, its use must be carefully balanced against potential damage to nearby organs such as the bowel and spine.

Chemotherapy has limited effectiveness in many retroperitoneal sarcomas but remains part of the treatment for specific histological types like Ewing sarcoma or rhabdomyosarcoma. It may be given before surgery to shrink the tumor (neoadjuvant) or after surgery to reduce recurrence risk (adjuvant). Chemotherapy protocols are based on tumor type and patient tolerance, and some rare retroperitoneal tumors such as lymphoma may respond well to systemic therapy alone.

Histological Subtypes and Their Clinical Behavior

Retroperitoneal cancers encompass a wide range of histological subtypes, with soft tissue sarcomas being the most common. Among these, liposarcomas and leiomyosarcomas dominate. Liposarcomas can be well-differentiated, dedifferentiated, or pleomorphic, each with different prognoses and recurrence patterns. Well-differentiated types tend to grow slowly but recur locally, while dedifferentiated forms are more aggressive and prone to metastasis.

Leiomyosarcomas arise from smooth muscle tissue and often involve the vena cava or uterine remnants. These tumors are more aggressive and carry a higher risk of hematogenous spread. Other rare subtypes include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, fibrosarcomas, and solitary fibrous tumors, each with unique biological behaviors and responses to treatment.

The clinical behavior of these subtypes dictates the therapeutic strategy. For instance, liposarcomas benefit more from complete surgical resection, while leiomyosarcomas may require systemic therapy due to their metastatic potential. This distinction is crucial when considering long-term management and follow-up.

Prognosis and Survival Outlook

The prognosis for retroperitoneal cancer depends on several interrelated factors: histological subtype, tumor grade, resectability, and recurrence pattern. Low-grade tumors that can be completely removed tend to have favorable outcomes, with 5-year survival rates approaching 70%. In contrast, high-grade, unresectable, or recurrent tumors have significantly poorer outcomes, with survival rates sometimes dropping below 20%.

Local recurrence is the most common cause of treatment failure, often due to microscopic disease left behind during surgery. Some studies suggest that even with complete resection, up to 50% of patients experience recurrence within five years. Long-term survival requires not only initial tumor control but also aggressive management of recurrences, often involving repeat surgeries and systemic therapy.

One key nuance is that prognosis also varies by tumor biology. For example, patients with well-differentiated liposarcomas may survive many years with repeated surgeries, while those with high-grade leiomyosarcomas may progress rapidly.

Staging and Grading Retroperitoneal Tumors

| Parameter | Description |

| Tumor Size | Measured in centimeters, often large at diagnosis (>10 cm) |

| Tumor Grade | Indicates aggressiveness: low, intermediate, or high based on mitotic rate |

| Tumor Histology | Determines subtype: liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, etc. |

| Local Invasion | Involvement of nearby organs (kidneys, vessels) |

| Lymph Node Involvement | Rare in sarcomas but relevant for lymphomas or carcinomas |

| Distant Metastasis | Spread to liver, lungs, bones |

| Resectability | Whether complete surgical removal is feasible |

Staging is based on size, grade, and spread, using AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) guidelines. High-grade tumors with distant metastasis are considered advanced stage, often requiring palliative rather than curative treatment. Grading reflects the tumor’s growth speed and is a vital predictor of behavior and survival.

Monitoring and Follow-Up After Treatment

Once primary treatment is complete, structured follow-up is critical for early detection of recurrence or metastasis. For most patients, this involves physical examinations, imaging studies such as CT or MRI scans every 3 to 6 months in the first two years, and annually thereafter. Surveillance intervals are guided by the tumor’s grade and the risk of recurrence.

For low-grade liposarcomas, less frequent imaging may suffice, while high-grade tumors require closer monitoring due to rapid growth potential. Some centers also incorporate PET scans for aggressive subtypes. Additionally, lab work including renal function and tumor markers (if applicable) may be part of regular assessment.

The role of long-term follow-up goes beyond surveillance. It also addresses the patient’s recovery from surgery or radiation-related complications, management of pain or gastrointestinal symptoms, and ongoing psychological support.

Recurrent and Metastatic Disease

Despite optimal treatment, many retroperitoneal sarcomas recur locally. Management of recurrence often involves repeat surgery, which can be technically demanding due to scar tissue and distorted anatomy. In select patients, re-resection may significantly prolong survival. Multidisciplinary tumor boards are essential to weigh the risks and benefits.

Systemic therapies are more often used in metastatic settings. Chemotherapy, while not uniformly effective, may provide palliation in metastatic leiomyosarcoma or other high-grade subtypes. Clinical trials may offer access to newer agents, including targeted therapies or immunotherapy, although these options are still under investigation for retroperitoneal sarcomas.

Palliative care becomes essential when tumors are unresectable or systemic disease causes significant symptoms. Pain management, bowel obstruction relief, and psychosocial support are key elements. Effective communication with patients and families about treatment goals is critical in advanced stages.

Quality of Life and Long-Term Outcomes

Living with retroperitoneal cancer — especially recurrent or metastatic forms — can significantly impact quality of life. Postoperative complications such as bowel dysfunction, nerve damage, and chronic pain are common, particularly after extensive resections. Emotional and psychological distress is also notable due to the disease’s uncertain course and physical burden.

Rehabilitation plays a central role in restoring function. This may include physical therapy for mobility, nutritional support for those with gastrointestinal symptoms, and psychological counseling. Long-term survivorship programs often coordinate these services, offering tailored care beyond cancer control.

Importantly, some patients can live for many years with intermittent treatment, particularly those with slow-growing tumors like well-differentiated liposarcomas. Quality of life considerations guide decisions on when to treat aggressively versus when to observe or offer palliative interventions.

Genetic and Molecular Profiling

Advances in molecular diagnostics have enabled deeper understanding of the genetic drivers behind retroperitoneal tumors. For instance, MDM2 amplification is frequently observed in well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcomas and is now used to distinguish them from benign lipomas. Similarly, alterations in TP53 or RB1 genes are associated with aggressive behavior in certain sarcomas.

These genetic insights are not only diagnostic but increasingly guide therapy. Some molecular subtypes may respond to targeted therapies or be eligible for clinical trials exploring novel agents. For example, tyrosine kinase inhibitors or CDK4/6 inhibitors are being explored in MDM2-positive tumors.

Understanding a tumor’s molecular profile also helps assess prognosis. Tumors with high mutational burden or chromosomal instability are often more aggressive. Molecular profiling is thus becoming standard practice at major cancer centers, shaping personalized medicine approaches.

Pediatric Retroperitoneal Tumors

Although rare, retroperitoneal tumors can occur in children, presenting unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. The most common pediatric retroperitoneal cancers include neuroblastoma, Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma), and rhabdomyosarcoma. These tumors often grow silently and are detected when they have reached a substantial size or caused organ displacement.

Children may present with nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal distension, loss of appetite, or urinary abnormalities. Imaging plays a vital role, with CT and MRI identifying both tumor characteristics and involvement of adjacent structures. Biopsy is essential for histological confirmation and risk stratification.

Treatment in pediatric cases usually combines surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, depending on the tumor type. For example, Wilms tumors often respond well to neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by nephrectomy. Outcomes in children can be more favorable than in adults due to better chemotherapy tolerance and tumor biology. However, long-term effects of therapy must be carefully managed to preserve growth and organ function.

Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Involvement

Retroperitoneal lymph nodes may become involved in metastatic spread from other cancers, such as testicular cancer, lymphoma, or gastrointestinal malignancies. In these cases, retroperitoneal disease does not originate in the soft tissue but arises through lymphatic dissemination.

Testicular cancer, particularly non-seminomatous germ cell tumors, often spreads to retroperitoneal nodes. In such patients, a procedure called retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) may be curative if chemotherapy is insufficient. Similarly, lymphomas that localize to the retroperitoneum often respond well to systemic therapy without surgical removal.

Distinguishing between primary retroperitoneal tumors and metastatic lymph node involvement is crucial for determining treatment. In some instances, enlarged nodes are the first sign of cancer, prompting further evaluation to find the primary site. Understanding the origin of the disease ensures appropriate and effective intervention.

Rare and Aggressive Retroperitoneal Malignancies

While most retroperitoneal tumors are sarcomas, some rare cancers present with especially aggressive behavior. These include retroperitoneal carcinomatosis, primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET), and desmoplastic small round cell tumors. Their presentation often mimics more common sarcomas but their course is far more lethal.

Desmoplastic small round cell tumors, for instance, are characterized by translocations involving the EWS gene and usually occur in adolescent males. These tumors spread rapidly and respond poorly to standard therapies. Early diagnosis is rare due to vague symptoms and late presentation.

Multimodal therapy is often attempted but with limited success. These cases highlight the need for better diagnostic tools and more effective treatment modalities. Genomic profiling, clinical trials, and novel immunotherapies may offer some hope in this subset of patients.

Psychological Support and Caregiver Involvement

Retroperitoneal cancer affects not only the patient but also their support network. The unpredictable course of disease, need for repeated surgeries, and ongoing symptom burden place emotional stress on both patients and caregivers. Depression, anxiety, and fear of recurrence are common and should be actively addressed.

Psychological support services, including therapy and support groups, help patients process their diagnosis and maintain quality of life. Caregivers also benefit from counseling, particularly when they are involved in complex decision-making or daily care activities.

In advanced stages, palliative care teams become essential not only for symptom management but also for emotional and spiritual support. A comprehensive approach that includes psychosocial care leads to better outcomes, not just in survival but in the patient’s overall experience.

FAQ

What is retroperitoneal cancer and where does it originate?

Retroperitoneal cancer refers to malignant tumors that arise in the retroperitoneal space, an area in the abdominal cavity behind the peritoneum. These tumors are typically soft tissue sarcomas and may develop from fat, muscle, or connective tissue.

How is retroperitoneal cancer typically diagnosed?

Diagnosis often begins with imaging such as a CT or MRI scan, followed by a biopsy to determine the exact type of tumor. Due to the deep location, symptoms may not appear until the tumor has grown large.

What are the early symptoms of retroperitoneal tumors?

Early symptoms can be vague and include abdominal discomfort, bloating, or back pain. As the tumor grows, it may press on organs or vessels, leading to more specific signs like bowel obstruction or leg swelling.

Which types of tumors are most common in the retroperitoneum?

The most common types include liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. These vary in aggressiveness and response to treatment.

How are retroperitoneal cancers staged?

Staging is based on tumor size, grade, local invasion, and presence of metastasis. Imaging and pathology reports are used to determine whether the cancer is localized, locally advanced, or metastatic.

What are the main treatment options?

Surgical resection with wide margins is the cornerstone of treatment. Radiation therapy is often used pre- or postoperatively, and chemotherapy may be added for aggressive or metastatic tumors.

Can retroperitoneal cancer be cured?

If detected early and completely removed surgically, some retroperitoneal cancers can be cured. However, due to frequent recurrence, long-term monitoring is necessary.

What are the risks of recurrence?

Recurrence is common, particularly for high-grade tumors. Local recurrence often happens within two years and requires prompt re-evaluation for potential surgery or other therapies.

How does retroperitoneal cancer affect nearby organs?

These tumors can compress or invade surrounding structures such as the kidneys, intestines, or blood vessels. This can lead to complex symptoms and complicate surgical removal.

Are there genetic factors involved?

Some retroperitoneal sarcomas are associated with specific genetic mutations, like MDM2 amplification. Genetic testing can aid in diagnosis and, in some cases, guide targeted treatment.

What are the differences in prognosis between tumor types?

Prognosis varies significantly. Well-differentiated liposarcomas have a relatively favorable outlook, while high-grade sarcomas and rare aggressive subtypes have poorer survival rates.

Is chemotherapy effective in retroperitoneal cancer?

Chemotherapy has limited efficacy in most sarcomas but may help control disease in certain subtypes like leiomyosarcoma. It is more commonly used in metastatic or inoperable cases.

Can retroperitoneal cancer affect children?

Yes, though rare, children can develop tumors like neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor in the retroperitoneum. These cancers often respond better to combined treatment protocols.

What role does palliative care play?

Palliative care is crucial when the disease is advanced or treatment options are limited. It focuses on relieving pain, managing symptoms, and supporting the patient emotionally.

How can caregivers support patients effectively?

Caregivers should be involved in medical discussions, encourage adherence to treatment, and seek emotional support for both the patient and themselves. Their role is essential for long-term care and quality of life.