Preventing and Living Well with Ringing in the Ears

Tinnitus and Its Impact on Health

Defining Tinnitus in Clinical and Everyday Terms

Tinnitus is the perception of sound-often described as ringing in the ears, buzzing, or hissing-in the absence of an external sound source. It is a symptom rather than a disease and can vary widely in intensity, tone, and duration. For some people, tinnitus is intermittent and barely noticeable; for others, it can be constant and intrusive. Clinically, tinnitus is categorized as subjective or objective. Subjective tinnitus, by far the most common form, is heard only by the affected individual, whereas objective tinnitus, which is rare, can sometimes be detected by an examiner using specialized equipment.

Medical professionals also distinguish between primary and secondary tinnitus. Primary tinnitus is idiopathic and often linked with sensorineural hearing loss-damage to the inner ear or auditory nerve that affects how sound is processed. Secondary tinnitus, on the other hand, has an identifiable underlying cause such as ear infection, vascular abnormalities, or the use of ototoxic medications. This classification helps guide evaluation and management, as secondary forms may resolve when the root condition is treated.

| Type | Description | Clinical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Subjective | Heard only by the affected person. | Most common form; often linked with hearing loss. |

| Objective | Can occasionally be detected by an examiner. | Rare; may result from vascular or muscular sources. |

| Primary | Idiopathic, often associated with sensorineural hearing loss. | No identifiable underlying cause. |

| Secondary | Related to identifiable medical or structural conditions. | May improve with treatment of the underlying cause. |

Prevalence and Real-World Impact

Tinnitus is a remarkably common auditory phenomenon, affecting approximately one in seven adults worldwide. While many individuals experience mild or temporary ringing in the ears, a smaller subset lives with persistent, bothersome tinnitus that significantly affects their well-being. The prevalence increases with age and is frequently associated with hearing loss or cumulative noise exposure from occupational or environmental sources.

- Approximately one in seven adults experience tinnitus globally.

- Severity and persistence often increase with age or hearing impairment.

- Tinnitus may disrupt sleep, concentration, and emotional stability.

Beyond the auditory perception itself, tinnitus can have a profound psychosocial impact. Many individuals report difficulty concentrating, disrupted sleep, and heightened stress or irritability. Over time, these effects may contribute to anxiety, low mood, or social withdrawal. Recognizing tinnitus as a condition that influences both mental and physical health underscores the importance of timely assessment, empathetic communication, and appropriate management.

Dispelling Common Misconceptions

Several misconceptions about tinnitus persist among patients and even within clinical settings. A common myth is that tinnitus always indicates permanent hearing loss or inevitable progression to deafness. In reality, tinnitus can occur with or without measurable hearing impairment, and its presence does not always signify ongoing ear damage. Another misconception is that nothing can be done to help those affected. While a single curative treatment does not exist, many effective strategies can reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life, including sound-based therapies and behavioural interventions.

- Myth: Tinnitus always means hearing loss.

Fact: It may occur with or without measurable hearing impairment. - Myth: Nothing can be done for tinnitus.

Fact: Multiple management options can lessen symptoms and improve quality of life.

Reframing tinnitus as a manageable and multifactorial symptom helps patients feel less helpless and encourages clinicians to take a comprehensive, supportive approach. Understanding both the biological mechanisms and the emotional toll of tinnitus lays the groundwork for compassionate, evidence-based care.

Causes and Mechanisms of Ringing in the Ears

Auditory and Systemic Causes

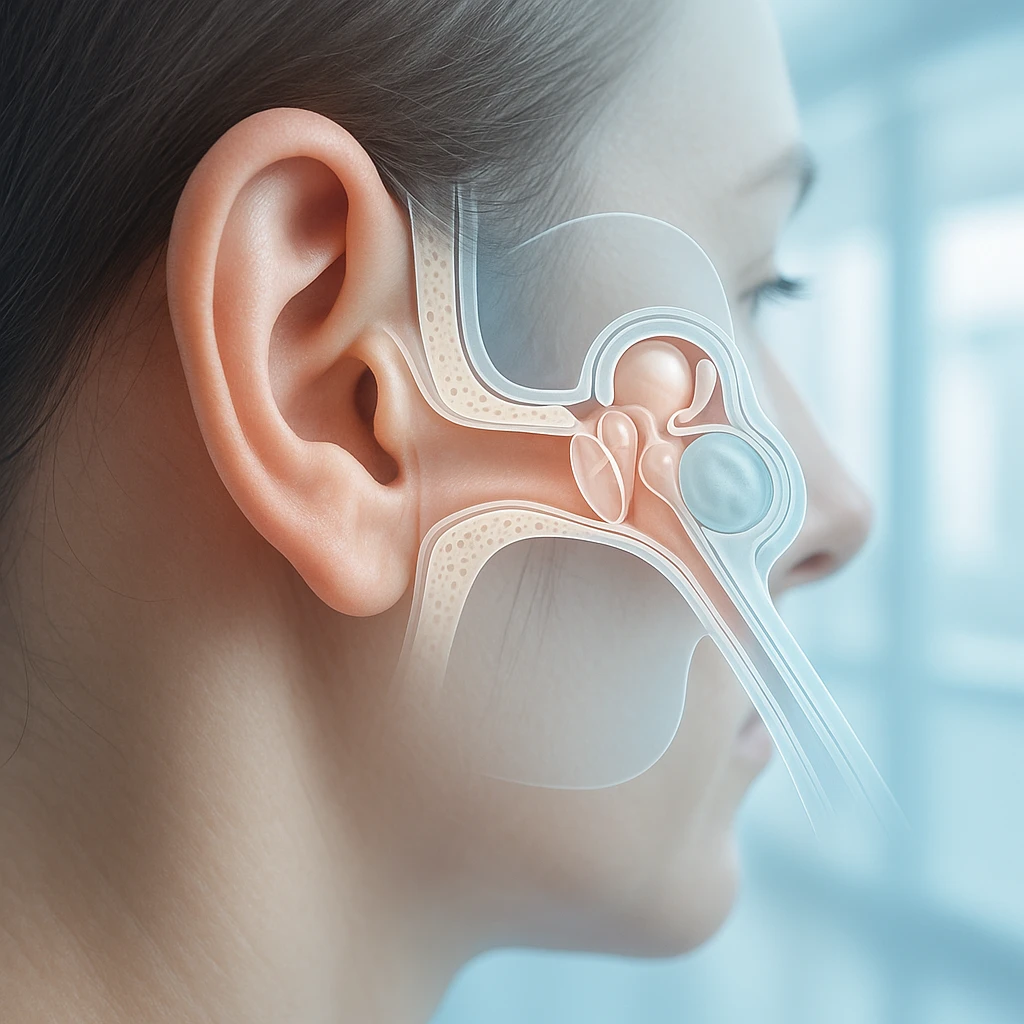

Tinnitus often arises from disruptions within the auditory system, particularly when normal hearing pathways are damaged or overstimulated. The most common associations include noise-induced and age-related sensorineural hearing loss. Prolonged exposure to loud noise can damage delicate hair cells in the cochlea, the part of the inner ear responsible for translating sound waves into electrical signals. Similarly, natural aging may lead to gradual degeneration of these sensory cells and their neural connections, reducing the brain’s ability to process external sounds accurately.

- Noise-induced hearing loss: Damage from prolonged or repeated loud sound exposure.

- Age-related hearing loss (presbycusis): Gradual deterioration of cochlear hair cells and auditory nerve connections.

- Ototoxic medications: Certain aminoglycoside antibiotics, chemotherapy agents, and high-dose salicylates that impair auditory function.

- Systemic factors: Vascular, metabolic, or neurologic conditions that alter blood flow or nerve signaling.

These causes can either trigger tinnitus directly or worsen its persistence once established.

How the Brain Creates Phantom Sound

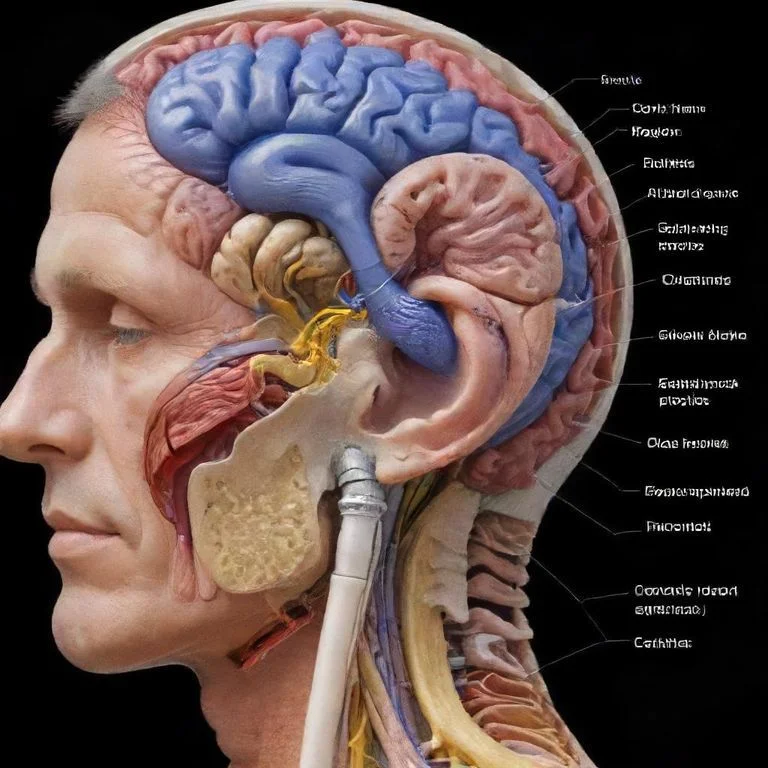

When the cochlea or auditory nerve is damaged, the brain receives less sensory input from the affected frequencies. In response, neural circuits within the central auditory pathways increase their internal “gain” to compensate for this reduced input. This process, while adaptive, can become maladaptive when it amplifies spontaneous neural activity, effectively generating a phantom perception of sound. The individual perceives this activity as ringing in the ears even though no external sound is present.

Over time, central neural plasticity-the brain’s ability to reorganize its networks-reinforces this pattern. Regions of the auditory cortex and related neural systems adapt to the altered input by sustaining hyperactivity and abnormal synchrony. This explains why tinnitus can persist even when the original ear injury or trigger has resolved: the brain continues to perceive sound due to these enduring changes in neural signaling.

Psychological and Lifestyle Factors

Although tinnitus originates in the auditory system, its intensity and impact are often influenced by emotional and lifestyle factors. Stress, anxiety, and sleep deprivation can heighten awareness of the sound and increase distress. The brain’s limbic system, which governs emotion, interacts closely with auditory pathways, making tinnitus more intrusive during times of heightened stress or fatigue. Conversely, relaxation and restorative sleep may lessen perception, highlighting the bidirectional relationship between psychological state and auditory processing.

- Stress and anxiety can amplify perception of tinnitus.

- Sleep deprivation increases sensitivity to internal auditory sensations.

- Emotional regulation and rest may reduce awareness and improve coping.

Understanding both the peripheral and central mechanisms of tinnitus helps clinicians and learners appreciate why this condition is complex and highly individualized. It also underscores the need for management approaches that address not only ear-related causes but also the broader neural and emotional context in which tinnitus develops and persists.

Recognizing Red Flags and Evaluating Tinnitus

Clinical Evaluation Framework

Evaluating tinnitus begins with a thorough clinical history that aims to determine its cause, duration, and impact. Key history elements include the onset and progression of symptoms, whether the tinnitus is constant or intermittent, and whether it affects one or both ears. Clinicians also inquire about recent or chronic noise exposure, use of medications known to affect hearing, and the presence of associated symptoms such as dizziness, hearing loss, or neurological changes. This structured approach helps distinguish benign, common cases from those requiring more targeted investigation.

- History essentials: onset, duration, laterality, noise exposure, medication use, associated symptoms.

- Physical examination: otoscopy to detect ear canal or middle ear abnormalities.

- Baseline testing: audiologic assessment, typically pure-tone audiometry.

A focused physical examination follows, including otoscopy to identify ear canal or middle ear pathology, such as wax impaction or infection. Baseline audiologic testing-typically pure-tone audiometry-is standard for most patients with persistent tinnitus. These findings help establish whether hearing loss is present and whether it is symmetric, guiding further evaluation and management.

Red Flags That Require Prompt Investigation

Although most tinnitus is benign and related to hearing loss or noise exposure, certain presentations warrant urgent or specialized assessment.

| Red Flag Feature | Possible Concern |

|---|---|

| Unilateral tinnitus with asymmetric hearing loss | Retrocochlear pathology (e.g., vestibular schwannoma) |

| Pulsatile tinnitus (in time with heartbeat) | Vascular abnormality or increased intracranial pressure |

| Sudden hearing loss or severe vertigo | Acute auditory or vestibular disorder |

| Focal neurological signs | Central nervous system involvement |

Recognizing these red flags ensures that potentially serious conditions are not overlooked and that patients receive appropriate diagnostic imaging or specialist care as early as possible.

When to See a Doctor

Seek medical evaluation promptly if tinnitus:

- Occurs in only one ear or is associated with asymmetric hearing loss.

- Is pulsatile or synchronized with the heartbeat.

- Appears suddenly or worsens rapidly.

- Is accompanied by dizziness, imbalance, or neurological symptoms.

- Persists beyond a few weeks without improvement.

For most individuals with chronic, non-urgent tinnitus, an initial evaluation by a primary care provider or audiologist is appropriate. However, timely recognition of atypical or concerning patterns allows for early detection of underlying ear, vascular, or neurologic disorders that may benefit from targeted treatment.

Evidence-Based Management of Ringing in the Ears

Setting Expectations and Building Understanding

For most individuals with tinnitus, the goal of treatment is not to eliminate the sound entirely but to reduce its impact on daily life. Clear, empathetic communication is essential-patients benefit when clinicians acknowledge that tinnitus is real and distressing while emphasizing that many people achieve meaningful relief through management strategies. Setting realistic expectations helps patients focus on coping and adaptation rather than seeking a single, curative solution.

Understanding that tinnitus is a symptom, not a standalone disease, also reframes the conversation. Effective care often involves a multidisciplinary approach that addresses hearing, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life. Patients who learn to interpret their symptoms within this broader context are better equipped to engage with therapy and achieve long-term improvement.

Therapeutic Options That Work

Several evidence-supported interventions can lessen tinnitus-related distress and improve functioning:

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT): Helps patients reframe their emotional response to tinnitus, reducing anxiety, frustration, and sleep disturbance over time.

- Hearing aids: Amplify environmental sounds to mask tinnitus and improve communication for those with hearing loss.

- Sound therapy devices: Introduce neutral background noise that decreases the contrast between tinnitus and silence, making the sound less intrusive.

- Comorbidity management: Addressing anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance enhances overall outcomes and quality of life.

Integrating these tools into daily routines helps patients regain a sense of control and reduces the emotional burden associated with tinnitus.

What Not to Rely On

Despite ongoing research, there is currently no medication proven to reliably eliminate chronic subjective tinnitus. Drugs targeting neurotransmitters, blood flow, or inflammation have shown inconsistent results in clinical trials. While pharmacologic treatment may help manage associated conditions such as anxiety or insomnia, it does not directly resolve the tinnitus itself. Patients should be informed that no single pill or supplement has been validated as a cure.

| Proven / Supported | Unproven / Not Recommended |

|---|---|

| Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) | Herbal supplements |

| Hearing aids and sound therapy | Magnetic or vibration therapy |

| Managing anxiety, depression, and sleep | Unregulated or “miracle” cures |

Alternative or unregulated remedies-such as herbal preparations, magnetic therapy, or unverified sound devices-lack solid scientific support and can carry financial or safety risks. Clinicians and learners should emphasize evidence-based care, guiding patients toward strategies supported by data and discouraging dependence on unproven methods. Maintaining a hopeful but realistic perspective allows for effective symptom control and improved quality of life.

Living With and Preventing Ringing in the Ears (Tinnitus)

Prognosis and Quality of Life Over Time

Tinnitus often follows a variable but generally stable course. For many individuals, the intensity and perception of the ringing in the ears remain steady or fluctuate over time rather than worsening. In some cases, the condition becomes less intrusive as the brain adapts and attention shifts away from the noise. However, a smaller proportion of patients experience persistent, severe tinnitus that significantly interferes with concentration, sleep, and emotional well-being.

Recognizing this variability helps patients and clinicians approach tinnitus with realistic optimism. Most people can achieve meaningful improvement in coping and quality of life through education, sound therapy, and psychological support. Addressing associated anxiety or depression is particularly important, as emotional distress can amplify how tinnitus is perceived.

Protecting Hearing and Preventing Exacerbation

Prevention focuses on protecting the auditory system and minimizing exposure to known risk factors. Key preventive measures include:

- Consistent use of hearing protection-such as earplugs or earmuffs-in loud environments.

- Avoiding prolonged exposure to high-volume music or occupational noise.

- Reviewing medication lists for potentially ototoxic drugs and discussing safer alternatives with healthcare providers.

- Maintaining cardiovascular health and managing stress to support auditory and neural function.

While not all tinnitus can be prevented, careful attention to modifiable risks reduces the likelihood of worsening symptoms and promotes long-term hearing health.

Myths vs Facts

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| Tinnitus always leads to hearing loss. | Many people with tinnitus have normal hearing, and the symptom does not necessarily indicate progressive damage. |

| Nothing can be done to help tinnitus. | Although there is no single cure, various evidence-based treatments-such as sound therapy and cognitive-behavioural approaches-can greatly reduce distress. |

| Tinnitus inevitably worsens with age. | For most individuals, tinnitus remains stable or becomes less noticeable over time rather than progressively deteriorating. |

Dispelling misconceptions empowers patients to take an active, informed role in managing tinnitus and in protecting their hearing health. Balanced education fosters resilience and encourages evidence-based prevention rather than fear or frustration.

Frequently Asked Questions About Ringing in the Ears (Tinnitus)

- Is ringing in the ears always a sign of hearing loss?

- No. Many people with tinnitus have normal hearing, and the condition does not necessarily indicate progressive or permanent damage to the ear.

- Why does tinnitus seem louder at night?

- The ringing often feels stronger in quiet environments when external sounds are minimal, allowing the internal noise to stand out more clearly.

- Can stress make tinnitus worse?

- Yes. Stress and anxiety can heighten awareness of tinnitus by increasing neural and emotional arousal, making the sound feel more intrusive.

- Are there medications that cause or worsen ringing in the ears?

- Some drugs, such as certain antibiotics, chemotherapy agents, and high doses of aspirin, are known to have ototoxic effects that may trigger or aggravate tinnitus.

- Does tinnitus get worse with age?

- For most people, tinnitus remains stable or fluctuates over time. Only a small number experience progressive worsening with age.

- Can ringing in the ears go away on its own?

- In some cases, especially after short-term noise exposure or infection, tinnitus can resolve spontaneously. Persistent cases, however, may require assessment and support.

- How is tinnitus diagnosed by doctors?

- Diagnosis usually involves a detailed history, ear examination, and hearing tests. Imaging or specialist referral may follow if red flag symptoms are present.

- What treatments can reduce the perception of ringing?

- Evidence-based therapies such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, sound therapy, and hearing aids help reduce tinnitus distress and improve daily functioning.

- Can lifestyle changes help manage tinnitus?

- Maintaining healthy sleep, managing stress, and avoiding loud noise can lessen symptom intensity and support overall auditory well-being.

- When should someone seek urgent medical advice for tinnitus?

- Immediate evaluation is important if ringing occurs in one ear only, is pulsatile with the heartbeat, or appears with sudden hearing loss or dizziness.