Pancreatic Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide

- Understanding the Pancreas and Its Functions

- Early Symptoms and Warning Signs

- Risk Factors and Genetic Predisposition

- Diagnostic Procedures and Imaging Techniques

- Tumor Staging and Classification

- Treatment Options: Surgery, Chemotherapy, and Radiation

- Personalized Oncology and Molecular Profiling

- Pancreatic Tumor Subtypes and Their Characteristics

- Challenges in Early Detection

- Role of Nutrition and Lifestyle During Treatment

- Palliative Care and Symptom Control

- Monitoring for Recurrence and Follow-Up Care

- Psychosocial Impact on Patients and Families

- Advances in Clinical Trials and Research

- Comparative Oncology: Lessons from Animal Models

- Hope Through Awareness and Innovation

- FAQ

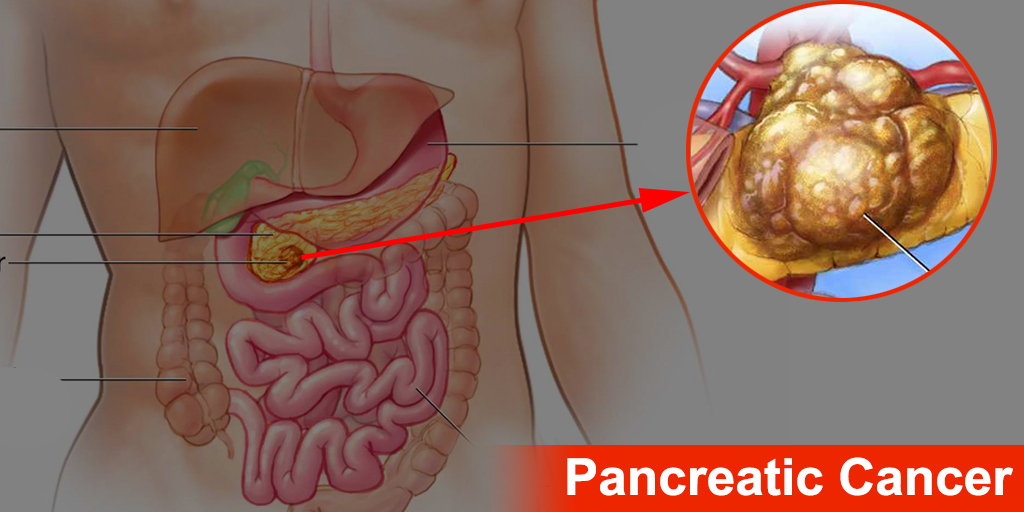

Understanding the Pancreas and Its Functions

The pancreas is a soft, elongated gland nestled deep within the abdomen, just behind the stomach. It plays a dual role in maintaining human health — on the one hand, it produces digestive enzymes that help break down proteins, fats, and carbohydrates in food; on the other, it synthesizes critical hormones such as insulin and glucagon that control blood sugar levels. These functions are carried out by two main types of cells: exocrine cells, which handle digestion, and endocrine cells, which regulate metabolism.

Pancreatic cancer arises when cells within this organ begin to grow uncontrollably. In most cases, this abnormal growth originates in the exocrine tissues — specifically, the ducts that transport digestive enzymes — and develops into what is known as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Less frequently, the cancer may arise from the endocrine cells, forming pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Both forms can interfere with pancreatic function and cause systemic disruptions throughout the body.

Early Symptoms and Warning Signs

Pancreatic cancer is infamous for its silent onset. Early symptoms are typically nonspecific, subtle, and often attributed to more benign conditions. One of the most commonly overlooked early indicators is persistent discomfort in the upper abdomen, which may radiate to the lower back. Patients often report an unusual sense of fullness after eating small meals or describe a gradual but noticeable loss of appetite. These symptoms frequently progress alongside unexplained fatigue and weight loss, which may be dismissed as stress-related or lifestyle-induced.

Another classic sign — jaundice, or the yellowing of the skin and eyes — usually appears when the tumor obstructs the bile duct. This symptom tends to develop later but may be an early sign if the tumor is located in the head of the pancreas. Dark urine, pale stools, and itching may accompany jaundice. Nausea, indigestion, and vomiting can also develop if the tumor impairs digestive flow.

It’s important to understand that the vagueness of these symptoms is part of what makes early detection so challenging. Patients and doctors alike may treat them symptomatically without investigating deeper causes. This delay often allows the disease to progress silently — a problem mirrored in other emerging health concerns. For instance, certain cosmetic or wellness interventions, such as those discussed in the article Can Microcurrent Cause Cancer , similarly raise questions about subtle, prolonged biological effects that may be easily dismissed until later consequences emerge.

Risk Factors and Genetic Predisposition

Although pancreatic cancer can affect anyone, it is far more likely to occur in individuals over the age of 60, and particularly among those with specific lifestyle or genetic risks. One of the most firmly established risk factors is cigarette smoking, which doubles the chance of developing pancreatic malignancy. Chronic pancreatitis — a persistent inflammation of the pancreas — is also a significant contributor, often resulting from alcohol abuse or inherited conditions.

New-onset diabetes, especially in older adults, has been increasingly recognized as a possible early manifestation of pancreatic cancer. In some cases, the tumor interferes with insulin production, leading to blood sugar disturbances that precede a cancer diagnosis by several months.

Genetics also play a pivotal role. Mutations in genes like BRCA2, ATM, and PALB2, as well as syndromes such as Lynch or FAMMM (familial atypical multiple mole melanoma), increase the lifetime risk significantly. Individuals with a strong family history of pancreatic or breast cancer should consider genetic counseling, especially if multiple relatives were diagnosed at younger ages. Recognizing these patterns allows for earlier surveillance and potential preventive strategies, including screening or even prophylactic surgery in high-risk individuals.

Diagnostic Procedures and Imaging Techniques

Diagnosing pancreatic cancer is a multi-step process that often begins after persistent symptoms prompt further investigation. Initial evaluation may involve standard abdominal ultrasound, although this method is often limited due to the pancreas’s deep location. More advanced imaging is usually required.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan is typically the first definitive imaging test and offers cross-sectional views of the pancreas, liver, and surrounding organs. If a suspicious mass is identified, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may follow. The EUS is especially useful because it allows both visualization and the ability to take a biopsy sample during the same procedure. This helps determine whether the mass is cancerous and, if so, what type.

Blood tests, particularly those measuring the tumor marker CA 19-9, can support diagnosis but are not specific enough for screening. CA 19-9 levels may also rise in conditions like cholangitis or pancreatitis, which makes them unreliable without supporting imaging. Biopsy-confirmed tissue remains the gold standard for diagnosis.

Tumor Staging and Classification

Once pancreatic cancer is confirmed, the next step is to determine the stage of the disease, which directly influences treatment decisions and prognosis. Staging describes how far the cancer has spread from its origin. This includes evaluating the size of the tumor, whether it has invaded nearby structures such as the bile ducts or blood vessels, and if it has metastasized to distant organs like the liver or lungs.

The TNM system is commonly used, where T refers to the size and extent of the primary tumor, N indicates whether lymph nodes are involved, and M denotes metastasis. Tumors are classified into four general categories: resectable (removable by surgery), borderline resectable, locally advanced (unresectable but still confined), and metastatic.

Accurate staging is achieved through a combination of imaging studies and exploratory procedures, often including diagnostic laparoscopy to detect small, otherwise invisible metastases. This staging process must be completed before any definitive treatment is planned, ensuring that interventions are both appropriate and personalized.

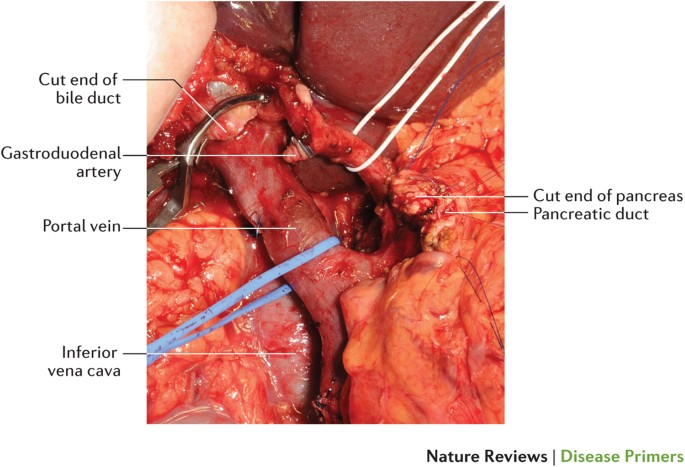

Treatment Options: Surgery, Chemotherapy, and Radiation

Treatment of pancreatic cancer typically involves a multimodal strategy, combining surgery, chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation. Surgery remains the only potentially curative option, but only about 15–20% of patients are eligible at the time of diagnosis due to advanced spread. The most common surgical procedure is the Whipple procedure (pancreaticoduodenectomy), which involves removing part of the pancreas, duodenum, gallbladder, and sometimes a portion of the stomach.

For patients with borderline resectable or locally advanced tumors, neoadjuvant chemotherapy may be used to shrink the tumor and improve the chance of successful surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy is often given after surgery to eliminate any remaining microscopic cancer cells and reduce recurrence risk.

Radiation therapy may be used either concurrently with chemotherapy (chemoradiation) or as a palliative measure to control symptoms. The choice of chemotherapeutic agents depends on the patient’s performance status and the cancer’s genetic profile. FOLFIRINOX, a combination of four drugs, is commonly used in patients who are strong enough to tolerate it.

Personalized Oncology and Molecular Profiling

Precision medicine is increasingly changing how pancreatic cancer is treated. By analyzing a tumor’s genetic mutations and molecular markers, oncologists can tailor therapies more effectively. For example, patients with BRCA mutations may respond better to platinum-based chemotherapy or PARP inhibitors, which target defects in DNA repair pathways.

Comprehensive genomic profiling is now often recommended for all pancreatic cancer patients, regardless of age or family history. It can identify targetable alterations, eligibility for clinical trials, and familial syndromes that may affect screening recommendations for relatives.

This approach mirrors the direction taken in other cancers — such as ovarian cancer — where tumor characteristics and genetic risk factors heavily influence management. Like in First Symptoms of Ovarian Cancer, where early signs often mask deeper genetic pathways, understanding the molecular foundation of pancreatic tumors helps reveal vulnerabilities that standard imaging may miss.

Pancreatic Tumor Subtypes and Their Characteristics

Here is a comparative overview of common pancreatic cancer types and their typical behavior, used by clinicians to inform diagnosis and treatment strategy:

| Tumor Type | Originating Cells | Frequency | Growth Rate | Hormonal Activity |

| Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | Ductal exocrine cells | ~90% of cases | Very fast | None |

| Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor | Hormone-producing endocrine cells | ~5–10% | Variable | Often present |

| Acinar Cell Carcinoma | Enzyme-producing acinar cells | Rare | Moderate | Occasional |

| Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm | Unknown origin (often in young women) | Very rare | Slow | Usually inactive |

Each of these subtypes behaves differently, with varying prognosis, treatment approaches, and symptom presentation. The most common form — ductal adenocarcinoma — is often diagnosed late and has the poorest outcome, while some neuroendocrine tumors may grow slowly and be discovered incidentally during unrelated imaging.

Challenges in Early Detection

Pancreatic cancer is particularly difficult to detect early due to its deep anatomical location and lack of specific symptoms in initial stages. Unlike breast or skin cancers, which may produce visible or palpable abnormalities, pancreatic tumors grow silently behind the stomach and do not typically cause pain or dysfunction until they affect surrounding structures.

Routine screening is not currently available for the general population. Even in high-risk groups, no single test has been proven effective enough for widespread use. Some efforts are focused on monitoring patients with strong family histories or known genetic mutations using a combination of MRI and endoscopic ultrasound, but these are resource-intensive and limited in availability.

This diagnostic invisibility makes pancreatic cancer especially lethal, as the disease is often already advanced by the time it is identified. By comparison, cancers like HER2-positive breast cancer have well-established screening and treatment frameworks — such as the TCHP regimen — that allow for early, aggressive intervention. Pancreatic cancer lacks these structured pathways, emphasizing the need for continued innovation in early detection methods.

Role of Nutrition and Lifestyle During Treatment

Maintaining adequate nutrition during pancreatic cancer treatment is a major challenge. The pancreas is essential for digesting food, and when its function is compromised — either by the tumor itself or by surgical removal — malabsorption can occur. This can lead to rapid weight loss, fatigue, and nutrient deficiencies that impair recovery and quality of life.

Patients often require pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) to aid digestion and manage symptoms like bloating, gas, and steatorrhea (fatty stools). High-protein, calorie-dense meals and frequent small snacks are usually advised. In advanced cases, feeding tubes or intravenous nutrition may be necessary to sustain weight and energy levels.

Dietitians play a crucial role in the care team, working alongside oncologists to adjust plans based on chemotherapy side effects, surgical outcomes, or tumor location. Emotional support also becomes essential, as appetite loss and food aversion can have psychological roots in addition to physiological causes.

Palliative Care and Symptom Control

For many patients, especially those with advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, palliative care becomes a cornerstone of treatment. This does not mean giving up on therapy, but rather prioritizing comfort, dignity, and quality of life alongside (or instead of) curative attempts.

Common symptoms requiring management include pain, digestive discomfort, fatigue, nausea, and anxiety. Pain control often involves opioid medications, nerve blocks, or radiotherapy aimed at reducing tumor burden. Jaundice can sometimes be relieved through stenting of the bile duct to restore bile flow.

Effective palliative care also addresses emotional and spiritual concerns. Social workers, psychologists, and chaplains may all be part of the team. The earlier palliative care is introduced — even concurrently with chemotherapy — the better the outcomes for patient well-being and satisfaction.

Monitoring for Recurrence and Follow-Up Care

After initial treatment, patients require long-term monitoring for recurrence. Pancreatic cancer has a high recurrence rate, even after successful surgical resection. Surveillance typically involves imaging (such as CT scans) every 3–6 months in the first two years, then less frequently over time. Blood tests for CA 19-9 are also used to track tumor activity, although their interpretation must be cautious due to possible false positives.

Post-treatment care must also include screening for treatment-related complications. For example, diabetes may develop in patients who undergo partial or total pancreatectomy. Digestive problems, chronic fatigue, and emotional distress are common and require ongoing support.

A survivorship care plan helps organize follow-up, rehabilitation, and patient education. These plans are tailored based on the initial tumor stage, type of surgery, response to therapy, and any comorbidities. Early integration of these strategies improves quality of life and may help identify new treatment options if recurrence occurs.

Psychosocial Impact on Patients and Families

Pancreatic cancer is not only a physically devastating diagnosis — it also takes a profound emotional toll on both patients and their loved ones. The typically poor prognosis, aggressive course, and grueling treatments leave many individuals overwhelmed, frightened, and struggling to process what lies ahead. Feelings of anxiety, depression, hopelessness, and existential fear are all common and should be addressed as actively as physical symptoms.

For families and caregivers, the emotional burden is equally intense. They often must balance logistical support, financial stress, and emotional reassurance while coping with their own grief. Open conversations, support groups, and access to professional mental health care are essential from the earliest stages of diagnosis.

Hospitals and cancer centers now recognize the importance of integrative care that includes psychologists, palliative care counselors, and survivorship coordinators. Offering these services early — not just in advanced or end-of-life scenarios — improves treatment adherence, quality of life, and emotional resilience for both patients and caregivers.

Advances in Clinical Trials and Research

While the standard treatments for pancreatic cancer have remained relatively consistent in recent years, new hope lies in the realm of clinical trials. Ongoing research is investigating immunotherapy agents, targeted therapies, vaccines, and novel combinations of chemotherapy. Some trials focus on disrupting specific molecular pathways involved in tumor growth and metastasis, especially in patients with actionable mutations like BRCA2 or KRAS G12C.

The personalized medicine movement has spurred a new wave of precision trials that assign patients based on tumor genetics rather than cancer type alone. Basket trials, for example, allow patients with different cancers but similar mutations to receive the same therapy. Pancreatic patients with rare molecular profiles may benefit from these expanded criteria.

Enrollment in a clinical trial can offer access to cutting-edge treatments not yet available elsewhere, often with close monitoring and enhanced support. While not every trial will be curative, participation may improve quality of life, extend survival, or help advance research that benefits future patients. For many facing limited options, clinical trials are a vital frontier of hope.

Comparative Oncology: Lessons from Animal Models

Animal studies have played a critical role in shaping our understanding of pancreatic cancer progression and treatment. Researchers often turn to mouse and dog models to evaluate new drug responses, tumor behavior, and metastatic mechanisms. Comparative oncology — the study of cancer across species — helps identify genetic patterns, immune responses, and treatment outcomes in a biologically relevant environment.

For example, spontaneous tumors in canines often mimic human cancers more closely than lab-induced models. In veterinary settings, conditions like spinal cancer in dogs have shown how tumors interact with surrounding tissues and how immune suppression influences disease progression. Such studies contribute valuable insights to human medicine, helping accelerate the translation of preclinical findings into clinical application.

The future of pancreatic cancer therapy may rely heavily on these models, especially as new immunotherapies and gene-editing techniques are developed. Cross-species collaboration will remain vital to understanding why pancreatic tumors are so resistant — and how we can outsmart them.

Hope Through Awareness and Innovation

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most aggressive and deadly forms of cancer, often diagnosed at an advanced stage and resistant to standard treatments. Yet within this grim reality lies hope — through early awareness, patient advocacy, scientific discovery, and integrated care.

Early recognition of symptoms, proactive evaluation in high-risk individuals, and improved access to imaging and molecular profiling all contribute to better outcomes. Multidisciplinary teams, palliative care integration, and mental health support ensure that patients are treated as whole people, not just cases. And for those navigating recurrence or advanced disease, clinical trials and novel therapies continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible.

Progress is slow, but it is real. By fostering awareness and continuing to invest in personalized research, we move one step closer to making pancreatic cancer not just treatable — but survivable.

FAQ

What are the first symptoms of pancreatic cancer I should watch for?

The earliest symptoms are often vague, including abdominal discomfort that may radiate to the back, unexplained weight loss, reduced appetite, and mild digestive disturbances. Jaundice can also be an early indicator if the tumor obstructs bile flow. These symptoms are easily mistaken for other conditions, making vigilance and persistence in follow-up crucial.

Is there a screening test for pancreatic cancer?

Currently, there is no universally accepted screening test for the general population. In high-risk individuals, such as those with genetic predispositions or strong family histories, periodic imaging with MRI or endoscopic ultrasound may be recommended as part of a surveillance program.

How is pancreatic cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of imaging (like CT or MRI), endoscopic ultrasound with biopsy, and blood tests such as CA 19-9. A definitive diagnosis is made when cancer cells are confirmed through tissue sampling. Accurate staging follows to guide treatment.

What is the prognosis for pancreatic cancer?

Unfortunately, pancreatic cancer has a poor prognosis, with a five-year survival rate under 12%. However, outcomes vary significantly based on how early the cancer is detected and whether surgery is an option. Patients with small, localized tumors have better chances for long-term survival.

Can pancreatic cancer be cured?

A complete cure is possible, but only in a small percentage of patients — typically those with localized disease eligible for surgical removal. Most patients receive a combination of therapies aimed at controlling the disease, improving symptoms, and prolonging life.

What treatment options are available?

Treatment may include surgery (such as the Whipple procedure), chemotherapy, radiation, or a combination. In advanced cases, palliative care becomes central. Precision therapies and clinical trials are increasingly available and may offer additional options.

Is pancreatic cancer hereditary?

Yes, about 10% of cases are linked to inherited genetic mutations, including BRCA2, PALB2, and genes associated with Lynch syndrome. If you have a family history of pancreatic or breast cancer, genetic counseling and testing may be appropriate.

What is CA 19-9 and how is it used?

CA 19-9 is a tumor marker that can be elevated in pancreatic cancer. It’s used to monitor disease progression or response to treatment but is not reliable for diagnosis alone because it can also be elevated in benign conditions like pancreatitis or bile duct obstruction.

How does pancreatic cancer affect digestion?

The pancreas produces enzymes essential for digestion. When cancer disrupts this function — or when part of the pancreas is removed — patients often experience fat malabsorption, bloating, and diarrhea. Enzyme replacement therapy is commonly needed to manage these effects.

Can pancreatic cancer cause diabetes?

Yes. Pancreatic cancer can impair insulin production, leading to new-onset diabetes, especially in older adults. In some cases, sudden or unexplained diabetes may be an early sign of an underlying pancreatic tumor.

What are the side effects of chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer?

Side effects depend on the drug regimen but may include fatigue, nausea, appetite loss, neuropathy, and low blood counts. Newer protocols like FOLFIRINOX are effective but intense, so side effect management is essential to maintaining treatment schedules.

Are clinical trials a good option for pancreatic cancer patients?

Yes. Clinical trials can offer access to new treatments not yet widely available. They are especially important for patients with advanced or treatment-resistant disease. Many trials now focus on personalized approaches based on genetic or molecular profiling.

What’s the role of palliative care in pancreatic cancer?

Palliative care focuses on symptom relief, emotional support, and quality of life. It is appropriate at any stage and often runs parallel to active cancer treatment. Early integration improves both patient comfort and overall treatment outcomes.

Can I live a normal life after pancreatic cancer treatment?

While recovery is challenging, many patients go on to live fulfilling lives after treatment. Long-term follow-up, nutritional support, mental health care, and lifestyle adjustments all contribute to improved quality of life.

What questions should I ask my doctor if I suspect pancreatic cancer?

Ask about your risk factors, whether your symptoms warrant imaging, and what steps are needed to confirm a diagnosis. If cancer is confirmed, ask about treatment goals, available clinical trials, and support services — including nutrition, palliative care, and counseling.