Can You Get a Nose Job While Having Cancer?

- Foreword

- 1. Understanding Rhinoplasty

- 2. Cancer and Surgical Considerations

- 3. Medical Eligibility for Rhinoplasty During Cancer

- 4. Risks and Benefits Analysis

- 5. Reconstructive Surgery Post-Cancer Treatment

- 6. Insurance and Financial Considerations

- 7. Psychological and Emotional Aspects

- 8. Expert Opinions and Guidelines

- 10. Unique Considerations

- FAQ

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

The question might catch some people off guard: Can you get a nose job while having cancer? At first glance, it might sound indulgent—or even inappropriate. But pause for a moment and really consider it. Who gets to define what’s appropriate during or after a cancer diagnosis? And why should the desire to reclaim your appearance, your sense of self, or even your airway be treated as somehow secondary to survival?

This isn’t a question rooted in vanity. It’s a question that lives in the space between survival and selfhood. Between managing illness and managing identity. For some, it comes after a skin cancer excision that left the nose visibly changed. For others, it surfaces quietly during remission—a yearning to take back control after months or years of passivity in the face of medical necessity. Sometimes it’s about aesthetics. Sometimes it’s about breathing, sleeping, or facing the mirror without flinching. But always, it’s about the person behind the patient.

This article was written for that person. For the one who’s wondering if surgery like rhinoplasty is possible—or safe—while navigating the physical and emotional aftermath of cancer. And not just in clinical terms, but in real, lived ones: logistics, risks, timing, costs, expectations, emotions.

Here, you’ll find more than quick answers. You’ll find the full picture—medical insight, expert perspectives, hidden variables, and the kinds of questions doctors don’t always remember to address unless you ask. We’ve also included the voices of patients who’ve been there—who’ve grappled with the same uncertainty and emerged on the other side with clarity, closure, or confidence.

If you’re seeking a final-stop resource—something comprehensive, respectful, and genuinely useful—you’re in the right place.

Let’s begin.

Understanding Rhinoplasty

Let’s begin with the basics—but not the boring kind.

If you’ve ever wondered what exactly happens when someone “gets a nose job,” you’re in good company. Rhinoplasty, as it’s formally known, is one of the most commonly performed plastic surgeries worldwide. But it’s not just about vanity or celebrity makeovers. Rhinoplasty spans a wide spectrum of purposes, from aesthetic refinements to restoring normal breathing after trauma or disease. It’s not a one-size-fits-all operation, and that nuance becomes especially critical when we’re talking about individuals who are also dealing with cancer.

So, what is rhinoplasty, really?

At its core, rhinoplasty involves reshaping the cartilage, bone, and skin of the nose. Depending on the patient’s needs, the procedure might involve making the nose smaller, refining the nasal tip, straightening a deviated septum, or even reconstructing entire sections of the nose lost to injury or surgery. It can be done through “open” techniques (with an incision across the columella—the tissue between the nostrils) or “closed” techniques (where incisions are made inside the nostrils). The approach depends on what’s being corrected, how much access the surgeon needs, and, crucially, the patient’s overall health.

Now, a question that comes up more often than you might think: Is there a difference between cosmetic and functional rhinoplasty? Yes, and the distinction matters. Cosmetic rhinoplasty is performed to change the appearance of the nose—its shape, size, profile, or symmetry. Functional rhinoplasty, on the other hand, addresses breathing issues or structural deformities. Then there’s a third, often overlooked category: reconstructive rhinoplasty, which becomes particularly relevant when cancer enters the picture.

Why do people get nose jobs if it’s not about looks?

Because sometimes, it’s about survival—or at least, recovery. Reconstructive rhinoplasty can be essential for patients who’ve undergone surgery for skin cancers like basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma on the nose. These cancers can leave defects that aren’t just disfiguring, but also compromise nasal function. In those cases, reconstruction isn’t elective—it’s restorative. And while some may still refer to it as a “nose job,” the medical and emotional weight behind it is very different.

Let’s put it plainly: rhinoplasty isn’t a vanity procedure for everyone. In fact, for patients dealing with or recovering from cancer, it can be about reclaiming something lost. A face is not just a face—it’s your identity, your social currency, your way of communicating with the world. The nose sits at the center of it all. Its absence or distortion can deeply affect how someone feels about themselves, far beyond what we typically imagine when we hear “plastic surgery.”

Is now the right time?

This is the elephant in the room. If someone is undergoing cancer treatment, is this kind of surgery appropriate—or even possible? That question opens up a host of considerations, which we’ll explore in the next sections. But to even get to that point, we need to start with clear, medically grounded definitions. Not all “nose jobs” are created equal, and not all patients considering one are doing so for the same reasons.

This might sound like an outlier concern, but cancer patients often ask about elective procedures. It helps to consider the risks discussed in Terminal Cancer Couloir, especially for late-stage decisions.

So as we move deeper into this discussion, keep this in mind: understanding the procedure in all its complexity is the first step toward deciding whether it makes sense in the context of a cancer diagnosis or recovery. Whether you’re thinking about it for yourself or researching for a loved one, you deserve more than a superficial answer. Let’s keep going.

Cancer and Surgical Considerations

Let’s say you’re in the middle of cancer treatment—or just starting to find your feet after it. Somewhere in the fog of appointments, fatigue, blood tests, and scans, this question bubbles up: Can I—or should I—get a nose job right now? It may seem out of place at first glance. But the truth is, it’s not unusual for cancer patients to contemplate procedures that help them feel more whole, more like themselves, especially when a sense of bodily autonomy has taken a hit.

So where does elective surgery like rhinoplasty fit into the picture of cancer care? To answer that, we need to understand what cancer and its treatments do to your body—and how that intersects with the demands of surgery.

Cancer treatment is not a neutral background condition.

Let’s get that straight. Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy—these aren’t just passive background elements to be worked around. They actively change the terrain of your physiology. They suppress your immune system, affect your blood counts, slow tissue regeneration, and sometimes even impair wound healing. That means the body you’re asking to undergo surgery is already busy waging war on a cellular level.

It’s not that you can’t have surgery while being treated for cancer. Sometimes, you must. If you need a mastectomy, a tumor resection, or a biopsy, there’s no waiting around. But elective surgeries—especially cosmetic ones—are a different story. They aren’t urgent, and because of that, the medical community usually urges caution.

Healing isn’t just about incisions and sutures—it’s systemic.

When your immune system is compromised, even small surgical wounds become liabilities. An infection that might’ve been minor in a healthy person can spiral into something more serious. Likewise, the body’s ability to form stable scar tissue, revascularize surgical sites, and manage inflammation is altered under the biochemical cloud of ongoing cancer therapy.

That’s why timing matters so much. There’s a fundamental difference between a person who’s in remission, no longer on active treatment, with robust blood counts and a good performance status—and someone mid-chemo, fatigued, with neutrophils barely hanging on. One may be a candidate for elective rhinoplasty, the other very likely not. And this isn’t about gatekeeping; it’s about safety.

But here’s where things get more nuanced: not all cancers or treatments carry the same weight.

For example, someone being monitored for low-grade prostate cancer might be in a completely different risk category than someone being actively treated for acute leukemia. A woman on long-term endocrine therapy for breast cancer may not face the same surgical healing challenges as someone undergoing concurrent chemoradiation for nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

It’s also worth considering the intent of the rhinoplasty. If it’s cosmetic, the medical team is going to evaluate risks with a particularly strict lens. If it’s reconstructive—say, part of the process of repairing damage from Mohs surgery after nasal skin cancer—the calculation shifts. Surgeons and oncologists may be more inclined to proceed, especially if the reconstruction is considered functionally or psychologically necessary.

Now, you might be wondering: What if I feel physically fine? What if my cancer is stable and I just want to take control of something—anything—about my body? That impulse is deeply human, and not wrong. In fact, regaining a sense of agency through bodily changes can be a powerful form of psychological healing. But that doesn’t override the need for a clear-eyed look at your current treatment landscape. Because even if you feel well, your labs and immune status might tell a different story.

The best answers come not from plastic surgeons alone, but from multidisciplinary dialogue.

Your oncologist knows your treatment schedule, your white blood cell counts, your healing capacity. Your surgeon understands the physiological demands of rhinoplasty. The magic happens when those professionals talk to each other—not just to you. If a rhinoplasty is on your mind, you’ll want a coordinated response that looks at your whole picture, not just the nose.

To sum up? It’s not a flat “no,” but it’s definitely not a simple “yes.” Surgery while undergoing cancer treatment is possible in select, well-timed, well-managed situations. But it demands a higher standard of caution, more thorough screening, and an understanding that healing is about more than incisions—it’s about the entire system working in harmony.

And if that system is already busy fighting cancer, you may need to wait until it’s less occupied before asking it to do something else—even something deeply personal.

Medical Eligibility for Rhinoplasty During Cancer

Let’s get practical now. Suppose you’re still seriously considering rhinoplasty during or after your cancer journey—what exactly determines whether you’re a viable candidate? This isn’t a philosophical exercise anymore. At this stage, the question gets real, and so do the answers.

Medical eligibility for surgery—any surgery, not just rhinoplasty—hinges on far more than the desire to do it. The human body is a complicated machine, and in the context of cancer, it’s also a recovering battlefield. Surgeons must weigh not only the technical feasibility of the procedure but also whether your body is equipped to handle it at this particular moment in time. That assessment unfolds along four major axes: the nature of your cancer, your current treatment status, your overall physical resilience, and your mental readiness. Each deserves a closer look.

First, not all cancers are created equal.

Let’s say you’ve been diagnosed with early-stage thyroid cancer and completed your treatment six months ago. You’re in remission, your scans are clean, and your lab work looks great. In this case, a plastic surgeon might greenlight elective surgery, provided your oncologist concurs. Now compare that with someone in active treatment for lymphoma, receiving multi-agent chemotherapy. The risk profile is worlds apart. Cancer isn’t a monolith, and your specific diagnosis matters. Not just in terms of organ system or prognosis, but in how it impairs—or doesn’t impair—your body’s ability to cope with additional physiological stress.

Staging matters, too. A person with Stage I breast cancer undergoing hormonal therapy has very different surgical tolerance than someone managing metastatic disease. It’s not about being “too sick,” per se—it’s about risk stratification. Rhinoplasty isn’t life-saving. That shifts the calculus in a field where non-essential interventions are rightfully scrutinized.

Next: Are you still in treatment—or is treatment behind you?

The timing of elective procedures in relation to cancer therapy is crucial. Most oncologists and surgeons agree: the best window for something like rhinoplasty is after treatment has ended and your body has had time to recover. But how long is “enough time”? That varies. Some patients bounce back quickly, especially after localized treatments or surgeries. Others need a longer runway, especially if they’ve endured extended chemotherapy, radiation, or bone marrow suppression.

There’s no universal waiting period, but a common rule of thumb is to wait at least six months after completing active treatment. Why? Because that’s often how long it takes for your immune system, blood counts, and healing capacity to stabilize—although in some cases, full recovery takes longer. This is why a preoperative workup for someone with a cancer history might look a little different: complete blood counts, clotting profiles, immune markers, and sometimes even cardiac clearance if chemotherapy has had systemic effects.

And then there’s the big, messy topic of “overall health.”

You might have heard the term “performance status” in oncology settings. It refers to how well you’re functioning in day-to-day life: Are you working? Walking? Eating normally? Needing assistance? This status is an excellent predictor of how well someone will tolerate surgery.

For rhinoplasty, which is relatively low-risk in healthy individuals, this might seem excessive. But in a cancer patient, even modest procedures need to be approached with extra diligence. Your nutritional status, for instance, plays a huge role in wound healing. If you’re underweight, losing muscle, or dealing with nausea or chronic fatigue, your body might not respond optimally to surgery—even if your cancer is technically stable.

Last, and arguably most overlooked: Are you mentally ready?

This is not a trivial question. Surgery is not just a physical act; it’s an emotional and psychological journey. Especially when your body has already been through trauma, disfigurement, or systemic change. It’s easy to underestimate the emotional gravity of seeking cosmetic surgery after a cancer diagnosis. You may be hoping to reclaim a sense of normalcy—or simply to feel more like yourself. That’s valid, but it needs to be matched by readiness. Are you prepared for the downtime? The discomfort? The chance that results might not be perfect on the first try?

Mental health evaluations aren’t standard in all cosmetic surgeries, but in cancer patients, they really should be part of the process. That doesn’t mean you’ll be denied surgery if you have anxiety or lingering trauma—but it does mean your care team should support you through it. You’re not just repairing a nose. You’re navigating identity, control, and healing on multiple levels.

So no, eligibility isn’t determined by a single yes/no checkbox. It’s a multidimensional evaluation. Your oncologist, your plastic surgeon, maybe even your therapist or primary care doctor—they all have a piece of the puzzle. And if all those pieces line up? Then yes, rhinoplasty might be possible. But only with the right timing, under the right circumstances, and with full transparency about the risks and rewards.

This isn’t a decision to rush. It’s one to plan. And that distinction might be the key difference between a successful procedure and one that introduces complications into an already complex journey.

Risks and Benefits Analysis

Let’s be honest—every surgery has risks. Even a routine wisdom tooth extraction comes with a consent form that looks like it was drafted by a lawyer having a bad day. So when we’re talking about something elective like rhinoplasty, and especially in the context of cancer or cancer recovery, you can expect the conversation around risks and benefits to be longer, deeper, and more layered than average. That’s not to scare you. It’s to make sure you understand the real landscape before you start planning anything.

First, the risks—and no, they’re not just theoretical.

Start with the obvious: wound healing. For anyone undergoing or recovering from cancer treatment, healing is rarely “typical.” Chemotherapy can blunt the body’s ability to regenerate tissue. Radiation, especially if it’s been directed anywhere near the head or neck, can impair vascularity—meaning the blood vessels in that area may not deliver nutrients and oxygen as effectively. That’s a problem when your body is trying to knit skin back together after surgery.

Now layer in the infection risk. Cancer, by definition, involves a compromised immune system—or at the very least, a system under immense stress. Add a surgical wound to the mix, and you’re potentially setting up a perfect storm: a body that’s not quite ready to defend itself, being asked to handle foreign bacteria from a surgical site. Surgeons are meticulous with sterility, but biology has no guarantees.

There’s also anesthesia to consider. Many people assume anesthesia is a controlled, low-risk part of surgery—and for the most part, it is. But in patients who’ve had extensive cancer treatment, especially if the heart, lungs, or kidneys have been affected, even general anesthesia demands a second look. Pre-op clearance might include cardiac function tests or pulmonary evaluations, not because anyone expects a crisis, but because no one wants to be caught off guard.

Another subtle but serious risk? Surgical stress. And we’re not talking about nerves or jitters here—we’re talking about physiological stress: elevated cortisol levels, increased inflammation, and systemic strain that can temporarily affect immune function. If you’ve recently finished cancer therapy and your immune system is still playing catch-up, this stress response might set you back in ways that aren’t immediately visible.

So with all these risks, why do it?

Because, for the right patient, the benefits can be powerful—and not just skin-deep. Rhinoplasty isn’t just about vanity or photos or symmetry. In many cases, it’s about reclaiming a sense of wholeness after cancer has left its mark.

Psychologically, the aftermath of cancer can be a quiet devastation. Your body has changed. Your routines, your energy levels, your mirror reflections—they all feel altered, and not always in ways you recognize. For some, rhinoplasty becomes a small but meaningful act of restoration. It’s not about chasing an ideal. It’s about regaining a personal baseline of confidence.

And let’s not overlook the functional side. Breathing problems caused by a collapsed nasal valve or post-cancer reconstruction issues aren’t cosmetic at all—they’re quality-of-life issues. Rhinoplasty, especially when it involves structural repair, can restore nasal airflow, correct asymmetry that interferes with sleep or exercise, and allow for better oxygenation.

There’s also a more intangible benefit: autonomy. When you’ve been a cancer patient, much of your medical journey is driven by necessity, protocol, and urgency. Elective surgery—especially when pursued with careful timing and preparation—can be a symbolic step back into the driver’s seat. You’re choosing something for yourself, not because it’s required, but because it reflects who you are and what you value.

Of course, all of this depends on one core assumption: that the risks are manageable in your particular case. And that’s not something you’ll find in a search result or a subreddit. That’s a decision your medical team makes collaboratively, weighing all the variables: blood counts, imaging results, comorbidities, surgical goals, and recovery timelines.

So what’s the real answer here? It’s this: If your health status supports it, and your motivations are sound, rhinoplasty can absolutely be worth the effort—even transformative. But it must be pursued with eyes wide open, guided by people who understand not just the art of facial surgery, but the biology of cancer recovery.

You’re not just a cosmetic surgery patient. You’re a whole human being, living at the intersection of medicine, healing, and self-definition. That’s a delicate space—but also a deeply meaningful one, if handled well.

Depending on the type and stage of cancer, you might also be interested in the implications of refusing or delaying treatment, such as those explored in Refusing Hormone Therapy for Breast Cancer.

Reconstructive Surgery Post-Cancer Treatment

Now let’s turn to a dimension of this topic that often gets glossed over in cosmetic surgery discussions: reconstruction. Unlike elective cosmetic rhinoplasty, reconstructive nasal surgery after cancer isn’t about refinement or enhancement—it’s about restoration. Reclaiming structure. Rebuilding function. And, in many cases, helping someone feel human again after disease has taken a toll on the most visible part of their face.

This is where things get both technical and deeply personal. Many patients with skin cancers—especially basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma—develop lesions on the nose, which is one of the most common sites for UV-related skin cancer. Treatment typically involves excision, sometimes via Mohs surgery, a precision-guided technique that removes cancerous tissue layer by layer. It’s highly effective, but it can leave behind significant defects, depending on the lesion’s size, location, and depth.

Here’s what most people don’t realize: even a seemingly “minor” cancer removal on the nose can result in disfigurement. Why? Because the nose is made up of a delicately balanced interplay of cartilage, bone, skin, and soft tissue. It has minimal redundancy—meaning there’s not a lot of extra material to go around. So when something’s removed, it often requires more than just a simple patch job. You’re not just closing a hole. You’re recreating a contour, a nasal tip, a bridge, a functional airway.

That’s where reconstructive rhinoplasty comes in.

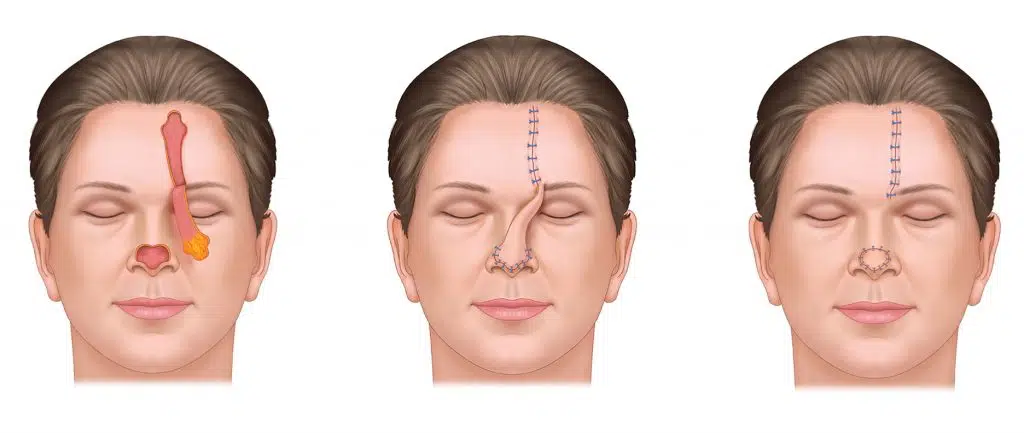

Depending on the extent of the surgical defect, reconstructive options range from small local flaps (where nearby skin is moved into the area) to cartilage grafts (often harvested from the ear or rib) to more complex, multi-stage procedures involving forehead flaps or free tissue transfer. These are not purely aesthetic procedures. They are designed to recreate form and function, and sometimes they are performed in stages over many months.

Does that mean these procedures are more invasive? Sometimes, yes. But they’re also more medically justified, and that matters when it comes to both surgical planning and insurance coverage. In fact, many reconstructive procedures following cancer resection fall under the umbrella of medically necessary surgery, which changes the conversation entirely. Suddenly, we’re no longer talking about optional beautification. We’re talking about the right to face the world without a deformity that wasn’t your choice to begin with.

And yes, timing still matters. Just because a reconstruction is necessary doesn’t mean it can happen right away. In some cases, especially when the original cancer was aggressive or located close to critical structures, surgeons may wait several months post-excision before beginning the reconstruction process. This allows time for the wound to stabilize, for pathology to confirm clear margins, and for the patient’s overall health to recover. In other cases, early intervention is actually preferred, to minimize scarring and tissue contraction.

Every case is different. A small, shallow excision near the nostril rim might be reconstructed the same day with a nasolabial flap. A deeper, more complex defect might require careful coordination between dermatologists, oncologic surgeons, and facial plastic surgeons. Some patients undergo what’s called “staged reconstruction,” where the initial surgery lays the groundwork (e.g., inserting a cartilage graft), and follow-up procedures refine the appearance and function over time.

Emotionally, the stakes are high.

If cosmetic rhinoplasty post-cancer is about reclaiming a sense of agency, reconstructive rhinoplasty is often about reclaiming dignity. Many patients report a sense of vulnerability or hypervisibility after nasal cancer surgery. Some avoid social interactions. Others feel that people are staring—or worse, pretending not to stare. The nose is, after all, central to the face. We orient our social perception around it. Even a minor irregularity can feel emotionally enormous.

Reconstruction offers more than skin coverage. It offers a way back into daily life, into relationships, into comfort with one’s own reflection. And that has real therapeutic weight, especially after the disorienting experience of cancer treatment.

And here’s the final point worth noting: These surgeries are often under-celebrated.

The craftsmanship behind nasal reconstruction is extraordinary—complex geometry, tissue engineering, structural support, and aesthetic subtlety all collide in a small but symbolically huge space. Surgeons in this field often view their work as both science and art. They aren’t just rebuilding a nose. They’re rebuilding confidence, identity, and the connective tissue of personhood.

So yes, reconstructive rhinoplasty after cancer is absolutely its own domain. It carries different goals, different standards, and often, a deeper emotional impact. Whether you’re contemplating it now or know someone who might be, understanding this difference is vital—not just to make informed decisions, but to appreciate what’s really at stake. Not a new look, but a restoration of the life that came before, and the face that still deserves to reflect it.

Insurance and Financial Considerations

Let’s pivot for a moment to something less clinical but no less critical: money. Whether or not a rhinoplasty is advisable during or after cancer treatment isn’t just a medical decision—it’s a financial one, too. And the distinction between what’s covered and what isn’t? That line is razor-sharp in theory, but fuzzy as hell in practice.

Here’s the reality: insurance companies care deeply about why you’re having surgery. Is it cosmetic, or is it medically necessary? That single distinction can determine whether you’re looking at a bill in the hundreds—or one that creeps into the five figures, out of pocket.

Cosmetic procedures? You’re on your own.

Let’s not sugarcoat it. If you’re seeking rhinoplasty purely for aesthetic reasons—whether to narrow the nasal bridge, smooth out a dorsal hump, or tweak asymmetry—insurance is not going to cover it. That’s the industry standard. Private insurers, Medicare, Medicaid—none of them regard elective cosmetic work as reimbursable, even if it improves your self-esteem or helps you feel like yourself again post-cancer. Their criteria are narrowly defined and strictly enforced.

But here’s where things get more interesting: functional and reconstructive rhinoplasty are often a different story.

If your surgery is addressing nasal obstruction, post-oncologic tissue loss, structural collapse from previous excisions, or breathing difficulties caused by scarring or anatomical disruption, then yes—insurance may consider it medically necessary. And in many of these cases, they’ll cover it. The key is documentation. Your surgeon will need to submit evidence: clinical notes, CT scans, photos, airway assessments, sometimes even sleep studies. It has to be unmistakable that this isn’t about looking better—it’s about restoring function or repairing damage caused by disease.

Where does cancer fit into this puzzle?

Ironically, cancer can sometimes “unlock” coverage for surgeries that might otherwise be dismissed as cosmetic. For example, if you’ve had skin cancer removed from your nose and require tissue reconstruction to restore structural integrity, insurers are far more likely to approve that process. Likewise, if you’re experiencing nasal collapse or airflow issues due to radiation-induced tissue fibrosis or post-surgical deformity, you’re not asking for a prettier nose—you’re asking to breathe normally. And that’s an argument insurance companies tend to respect.

But it’s not always smooth sailing. Denials still happen. Appeals still happen. And patients often find themselves in bureaucratic limbo: needing surgery, having a legitimate medical reason, but stuck in a paperwork battle between their surgeon and a claims department staffed by people who’ve never seen a nasal septum.

So what can you do to protect yourself financially? Start with transparency.

Your surgeon’s office should be up-front about costs. Not just the surgeon’s fee, but also the anesthesia fee, the facility fee, pre-op testing, post-op care, and possible revision procedures. These numbers add up quickly. And while reconstructive surgeries done in hospitals or academic centers may be bundled into cancer care plans, those done in private surgical centers often aren’t.

Ask about preauthorization. Ask what documentation will be submitted to the insurance company. Ask if there’s an in-network surgical team that specializes in post-cancer reconstruction. Ask what happens if your claim is denied. Good surgical practices will not only answer those questions—they’ll have systems in place to help you navigate the mess.

And then there’s the wildcard: hybrid procedures.

It’s not uncommon for a surgery to involve both functional and cosmetic components. Say your septum is deviated and causing chronic congestion, but while fixing it, you also want to reduce the width of your nasal tip. The former might be covered; the latter won’t. This split-billing scenario is legal and common—but it requires clear communication. Otherwise, patients are blindsided by unexpected charges for the “cosmetic portion” of a surgery they thought would be covered.

What about payment plans and financing?

Many plastic surgery clinics—especially those handling a high volume of cosmetic work—offer financing through third-party lenders. Think of them like medical credit cards: CareCredit, Alphaeon, and similar services. They offer structured payment plans, often with interest-free windows, to help patients manage out-of-pocket expenses. But tread carefully. Interest rates after the promotional period can be steep, and these accounts can quickly become burdensome if your financial situation changes.

So what’s the takeaway here?

If you’re considering rhinoplasty in the context of cancer recovery, your financial experience will be shaped as much by language and paperwork as by scalpels and sutures. The difference between “cosmetic enhancement” and “reconstructive repair” isn’t just academic—it can mean the difference between a bill your insurance absorbs and one that lands squarely in your lap.

You deserve to know that up front. And you deserve a care team that doesn’t just operate skillfully, but advocates smartly. The best results come not just from what’s done in the OR—but from what’s done behind the scenes to make your care sustainable, strategic, and accessible.

Psychological and Emotional Aspects

Let’s talk about the part of the conversation that often gets pushed to the margins—emotions. Not because they’re unimportant, but because medicine, even when it’s human-centered, still tends to prioritize what’s visible: scans, charts, incisions, sutures. And yet when it comes to decisions like having rhinoplasty during or after cancer, the emotional landscape isn’t just part of the story—it is the story.

Here’s something not enough people say out loud: facing cancer changes your relationship with your body. It just does. Maybe it’s subtle—a sense of betrayal, a new discomfort with scars or asymmetry, an unfamiliar silhouette in the mirror. Or maybe it’s more profound, like feeling disfigured after surgery, or alienated from the person you used to be. These feelings aren’t superficial. They’re not about vanity. They’re about identity, control, and grief—often layered on top of each other in complex, private ways.

Now put yourself in the mindset of someone contemplating rhinoplasty in that context. You’ve endured the physical, emotional, and existential upheaval of cancer. Maybe you lost part of your nose to a tumor, or your skin texture and facial shape changed after radiation. Or maybe nothing visible happened to your nose, but everything inside you feels different. It’s not uncommon to want to restore, revise, or reclaim something about your appearance—not to be someone new, but to reconnect with who you were before everything changed.

And here’s the crucial point: that desire is valid.

Too often, people—sometimes even healthcare professionals—dismiss these motivations as trivial or vain. But studies consistently show that body image plays a powerful role in post-cancer recovery. It’s linked to self-esteem, social reintegration, intimacy, even long-term mental health outcomes. When someone wants rhinoplasty after cancer, it’s rarely just about changing a nose. It’s about rebuilding something that was lost: confidence, familiarity, normalcy.

But let’s not pretend the decision is easy. It’s not.

The emotional terrain is tricky. For some, the idea of another surgery—especially one that isn’t mandatory—feels overwhelming. There’s fear of complications, of being disappointed by the results, of re-entering a medical space when you thought you’d finally escaped it. There’s also guilt. A surprising number of cancer survivors feel unsure whether they’re “allowed” to care about how they look. As if surviving should be enough. As if wanting more is indulgent.

That kind of self-policing is deeply unfair. Surviving cancer doesn’t mean giving up the right to your own body. It doesn’t mean accepting permanent changes you didn’t choose. And it certainly doesn’t mean you’re not entitled to pursue healing on your own terms—even if that healing includes a scalpel and a surgeon’s eye.

This is where mental health support becomes invaluable. Not because you need permission to want what you want—but because you deserve space to explore it. A good therapist, especially one experienced in oncology or body image issues, can help you unpack the layers: Why do you want this surgery? What do you hope it will change—not just externally, but internally? Are your expectations grounded in reality, or are they a placeholder for something that needs different kinds of care?

This isn’t about talking you out of rhinoplasty. Quite the opposite. It’s about ensuring that if you move forward, you do so with clarity. That you’re not chasing healing through a procedure that can only offer transformation on the outside. That you’ve made room for all the emotions—not just hope and optimism, but fear, doubt, and maybe even some sadness.

Also worth noting: the journey doesn’t end when the bandages come off. Postoperative recovery is not just physical. You might have mixed reactions to your reflection, especially if you’re still adjusting to other changes from cancer. Give yourself time. Healing is not linear. You’re not failing if it takes a while to feel fully “yourself” again. And you’re not alone if your reaction to a new nose is more complicated than you expected.

Ultimately, this process—deciding, preparing, recovering—is as psychological as it is surgical. And when done thoughtfully, it can be an extraordinary form of personal restoration. But no one should walk that road unsupported. You don’t just need a surgeon. You need a team. People who will recognize that you’re not rebuilding a nose. You’re rebuilding you. And that’s a project worth doing well.

Expert Opinions and Guidelines

Now that we’ve explored the personal and physiological sides of this decision, let’s zoom out and look at how the wider medical community views elective surgery—especially rhinoplasty—in patients undergoing or recovering from cancer. Because while your experience is uniquely yours, your care will inevitably intersect with the standards, policies, and practices shaped by decades of collective medical judgment.

So what do the experts say?

The overarching guidance from most major medical associations—whether it’s the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), or the broader surgical oncology community—is clear: elective procedures should be postponed during active cancer treatment unless there is a compelling functional or reconstructive need. That word “elective” is key. It doesn’t mean “unimportant.” It simply means non-urgent from a life-or-death standpoint.

And the logic is sound. When your body is actively managing malignancy—either fighting cancer cells, adapting to systemic therapies, or recovering from major interventions—every physiological resource is spoken for. Immune cells are diverted. Hormones are altered. Wound healing mechanisms are disrupted. And even if you feel fine, the internal picture might still be in flux.

That’s why expert recommendations almost always advise a recovery window after treatment ends. This isn’t a random waiting game. It’s about ensuring you’re not just done with treatment, but that your body has actually stabilized. Blood counts should be normalized. Inflammatory markers should be under control. Cardiac and pulmonary function should be back within baseline limits, especially if chemo or radiation affected those systems. In short, your body needs to be back in a condition where it can safely add something else to its to-do list—like surgical healing.

Now, let’s say you’re a few months post-treatment, feeling strong, and seriously considering rhinoplasty. What would a best-practice protocol look like?

First, your oncology team should be involved from the start. This isn’t just out of courtesy—it’s critical. Your oncologist can provide insight into your current remission status, your risk of recurrence, your immunocompetence, and whether there’s any reason to delay surgery further. They may also recommend specific pre-op labs or imaging that your plastic surgeon wouldn’t think to order.

Second, your plastic surgeon should have experience working with medically complex patients. Not every aesthetic surgeon is equipped to handle post-cancer care. Look for board certification in both plastic and reconstructive surgery. Ask directly about their experience with cancer survivors, especially those who’ve undergone radiation or had surgeries in the head and neck region. This is not the moment to prioritize convenience or cost. This is a moment to prioritize someone who understands both the art and science of what you’re asking for.

Third, multidisciplinary coordination is ideal. The gold standard, if you can access it, is care from a team that includes not just your oncologist and surgeon, but also a primary care physician, a dermatologist (especially if skin cancer was involved), and a mental health provider. Institutions like academic hospitals or cancer centers often have built-in pathways for this kind of coordination. Private clinics can do it too—it just takes more initiative to assemble the team.

It’s also worth noting that some professional bodies offer decision aids—tools to help patients and providers evaluate surgical readiness. These tools don’t give yes-or-no answers, but they do walk through criteria like immunologic recovery, nutritional status, psychosocial readiness, and long-term cancer prognosis. They’re not mandatory, but they’re increasingly used to ensure no one is rushing into surgery without a clear-eyed risk assessment.

What you won’t find in most guidelines, however, is permission. The medical world doesn’t give blanket green lights. It gives frameworks. And within those frameworks, your individual case has to be assessed on its own merits. The best guidelines are guardrails, not stop signs. They exist to make sure you’re not being reckless with your health—but they also respect that, once the risks are understood, the decision is yours.

Here’s what that really means: Experts are not here to tell you what to do with your body. They’re here to tell you how to do it safely, when to do it wisely, and how to build the right support around you. That’s a much more powerful kind of guidance than a rigid yes or no.

So when you bring this question to your care team—Can I get a nose job while or after dealing with cancer?—you’re not just asking for technical approval. You’re asking them to help you calibrate timing, safety, and readiness. And if they’re good at what they do, they won’t just give you a yes or no. They’ll give you a plan.

Also, if the cancer involves skin or facial tissue, this guide to Sunspots vs Skin Cancer might help you separate cosmetic from clinical priorities.

Unique Considerations

By now, you’ve probably gathered that rhinoplasty in the context of cancer isn’t a simple “book the date and show up” kind of situation. It’s more of a puzzle—one where your biology, your psychology, your goals, and your circumstances all have to align. But beyond the typical clinical considerations, there are a few elements that tend to fly under the radar—details that aren’t commonly discussed but could significantly influence your decision-making process or outcome.

Let’s start with surgical technique. Because yes, how the surgery is done matters.

In recent years, the world of rhinoplasty has quietly evolved. Minimally invasive approaches are gaining ground, particularly for patients who aren’t good candidates for longer surgeries or extended recovery periods. For cancer survivors—especially those with lingering fragility in the immune or vascular systems—this is a meaningful shift. Surgeons now have access to better tools for closed rhinoplasty (where incisions are hidden inside the nostrils), as well as more advanced grafting materials that reduce the need for harvesting cartilage from the ribs or ears. Some are even using 3D-printed custom implants for very specific reconstructions.

What does this mean for you? It means that if your candidacy for surgery hinges on minimizing risk and downtime, you may have more options than you think. Not every case is suitable for a less invasive approach, but if the anatomy and objectives allow, it could make recovery smoother and complication rates lower.

Another under-discussed factor is radiation fibrosis—a delayed effect of radiotherapy that can thicken tissues, reduce vascularity, and subtly alter the biomechanics of healing. Most plastic surgeons know about it, but not all general practitioners do. If you’ve had radiation to your head or neck, even years ago, make sure your surgical team considers this. It may influence flap selection, incision placement, or how aggressive your reconstruction can be.

Now, let’s talk about technology and planning, which are more cutting-edge than most patients realize. High-resolution imaging, computer-assisted surgical mapping, and digital morphing tools are now widely used in advanced facial surgery clinics. This isn’t just gimmickry—it’s useful, especially for cancer survivors. Being able to visualize outcomes with precision allows for more accurate conversations about expectations and feasibility. If you’re nervous about another change to your face, seeing a digital rendering beforehand (with surgical constraints considered) can be a game-changer in terms of confidence and clarity.

Then there’s telemedicine—and no, it’s not just a COVID-era workaround. Virtual consultations are now a fixture in many practices, particularly for the pre-screening and follow-up phases. This can be especially helpful for cancer survivors who live far from surgical centers of excellence, or who need to coordinate care with multiple specialists. A virtual consult doesn’t replace a physical exam, but it can lay the groundwork, answer early questions, and let you vet your surgeon without committing to travel and cost upfront.

And finally, let’s consider something intangible but important: narrative coherence.

What do we mean by that? Simply this—after cancer, many people are trying to rebuild not just their bodies, but their story. A coherent sense of self, a continuity that was fractured by diagnosis, treatment, side effects, losses. In that context, rhinoplasty isn’t just cosmetic or reconstructive—it’s symbolic. It can represent the final chapter in a long arc of recovery. Not everyone feels this way, but those who do often speak about the decision in almost narrative terms: “I needed to finish the story,” or “This was the last piece.”

That’s a unique consideration you won’t find in any surgical handbook or oncologic guideline. But it matters. Because sometimes, healing isn’t just about function or form. Sometimes it’s about feeling like the protagonist in your own life again.

So as you weigh your options, keep in mind that this journey doesn’t have to be dictated solely by biology or bureaucracy. Yes, those elements shape what’s possible—but they don’t define what’s meaningful. And in many cases, it’s the small, human-scale considerations—the details, the desires, the forward-looking hope—that give this decision its true weight.

FAQ

You’ve come this far. That probably means this question—Can you get a nose job while having cancer?—isn’t just theoretical for you. Maybe it’s personal. Maybe it’s emerging slowly, somewhere between remission and reinvention. Either way, you deserve clarity on the things that still linger—those details that aren’t always answered directly in consultations or glossed over in generalized guides.

So let’s wrap up with a few critical clarifications, not in a bullet-pointed flurry of half-answers, but in the spirit of everything this article has aimed to be: nuanced, respectful, and grounded in the reality that you’re not just curious. You’re considering.

1. Can someone undergo rhinoplasty while actively receiving chemotherapy or radiation?

Technically, it’s not impossible. But practically—and ethically—most surgeons will say no. Active treatment involves cellular warfare. Chemotherapy doesn’t just target cancer cells; it suppresses the entire immune system. Radiation compromises tissue quality. This makes surgical healing unreliable at best, and risky at worst. The stakes are too high for something elective. So while your desire may be strong, the timing likely isn’t on your side if you’re mid-treatment. You may simply need to wait.

2. What if the surgery is reconstructive after cancer-related nasal damage?

Different story. When surgery is required to restore nasal structure or function—whether due to tissue loss after Mohs surgery, collapse from radiation-induced fibrosis, or breathing obstruction following cancer resection—it’s no longer elective in the cosmetic sense. It’s part of recovery. Insurance often reflects this difference, and so does medical urgency. It may still need to be staged, and clearance from your oncology team is non-negotiable, but the green light is far more achievable when the surgery is reconstructive in intent.

3. How long after completing cancer treatment should someone wait before considering cosmetic rhinoplasty?

There’s no universal clock. Some bodies bounce back in three months. Others take a year or more. Most oncologists recommend a minimum of six months after completing active treatment, with labs and imaging confirming that your system is stable. The goal isn’t just for the cancer to be “gone” but for your physiology to be ready. Think of it like renovating a house after a flood—you don’t start laying tile until the foundation has dried and settled.

4. Will insurance pay for any of this?

They might, but only if there’s a functional or medical indication. That means obstruction of airflow, post-oncologic repair, or structural damage that impairs daily life. If your motivation is purely aesthetic—shaping the nose, smoothing a bump, refining the tip—it’s extremely unlikely to be covered. And if your surgery involves both cosmetic and functional components, expect the bill to be split accordingly. This is where documentation, pre-auth approvals, and a diligent surgical coordinator can save you from financial whiplash.

5. Are there alternatives for patients who aren’t ready—or eligible—for surgery yet?

Yes, and they’re worth discussing. Non-surgical rhinoplasty, using dermal fillers, can sometimes offer temporary visual improvement—especially for contour irregularities or minor asymmetries. It won’t fix breathing problems, and it doesn’t replace structural reconstruction, but for certain patients (especially those still recovering from treatment), it can serve as a confidence bridge until full surgery becomes viable. Think of it as a placeholder, not a final solution.

6. What kind of emotional support is available during this process?

More than most people realize. Cancer centers often provide post-treatment counseling, support groups, and even body image specialists trained to help you navigate these decisions. Reconstructive surgeons who work with cancer survivors usually have mental health professionals on their referral list. Use them. Not because you’re “unstable” but because you’re human. Wanting to change your face after cancer isn’t shallow—it’s layered. It’s about control, identity, and sometimes, the slow process of making peace with a body that didn’t get through unscathed.

7. What if I’m still unsure? What’s the harm in waiting?

In most cases, none at all. Time is often your ally here. Healing from cancer takes more than finishing a treatment plan. It takes emotional calibration, physiological stabilization, and sometimes, the passage of a few more seasons before the body and the psyche are truly aligned again. So if you’re unsure? Pause. Revisit the idea in six months. Talk to your oncologist, your primary care provider, your plastic surgeon—and your own gut. When it’s right, you’ll know. Or at least you’ll be ready to decide with clarity, not confusion.

This isn’t about rushing toward a version of yourself that looks “normal” again. It’s about reclaiming what was yours—on your timeline, in your own way. That deserves patience. And precision. And care.

Closing Thoughts

If you’ve read this far, you’re clearly not looking for a superficial answer. You’re not here for a quick yes or no, and that’s good—because no one dealing with cancer, surgery, identity, and healing should be handed an oversimplified script. These aren’t questions you ask lightly, and they shouldn’t be answered lightly either.

So let’s land this thoughtfully.

At the heart of all this is something bigger than noses, bigger than scars, bigger than even the medical facts: You. Not as a patient, not as a case, but as a full person standing at the intersection of what’s been endured and what comes next. That person deserves options. And maybe more than that—dignity in deciding what to do with those options.

Can you get a nose job while having cancer? It depends. On timing. On your body’s readiness. On whether it’s cosmetic or reconstructive. On whether your doctors agree it’s safe. But also—more quietly—on how ready you are, emotionally, to take that step.

Because this isn’t about vanity. It never was. It’s about continuity. When cancer slices through the story of your life, sometimes surgery becomes a way to stitch that narrative back together. Not because it erases what happened, but because it lets you move forward with a body that feels like yours again.

And make no mistake—this is your body. After months or years of doing what needed to be done—taking what doctors recommended, submitting to what was necessary—you now have a choice. Elective surgery, especially in the shadow of something as consuming as cancer, can feel radical in its voluntariness. That’s not frivolous. That’s power.

But power needs to be paired with wisdom. Not caution for its own sake, but discernment. Talk to your doctors. Make sure your recovery is stable. Understand the risks. Plan for the cost. Prepare for the emotions—because they will come, and they will be more layered than you expect.

And if it turns out that surgery isn’t right for you right now? That doesn’t close the book. It just means this chapter is still unfolding. You can revisit the decision later. Healing isn’t a straight line. And neither is reclaiming your sense of self.

So whether you go forward with surgery, wait it out, or ultimately decide it’s not what you need—know this: asking the question already mattered. It meant you were envisioning a future. It meant you still cared about how you move through the world. It meant you were choosing you, not just surviving, but seeking something more.

That’s not cosmetic. That’s courage.

And wherever your journey leads, you deserve care that honors every dimension of that courage—medical, emotional, personal. Here’s to healing, not just in body, but in identity. And here’s to doing it on your terms.