Nausea After Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer

Nausea After Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer: A Complete Clinical Overview

- Why Nausea Occurs in Ovarian Cancer Chemotherapy Patients

- The Mechanism Behind Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Its Relationship to Ovarian Cancer

- Prevalence of Chemotherapy-Related Nausea in Ovarian Cancer Cases

- What Causes Nausea in Ovarian Cancer Treatment: Beyond the Chemotherapy

- When Nausea Becomes an Emergency in Ovarian Cancer Care

- How Nausea Is Diagnosed and Monitored in Chemotherapy

- Effective Treatments to Ease Nausea in Chemotherapy

- Can Chemotherapy Nausea Be Prevented in Future Cycles?

- Will the Nausea Eventually Go Away?

- What Oncologists Say About Managing Nausea

- 15+ Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Nausea

Why Nausea Occurs in Ovarian Cancer Chemotherapy Patients

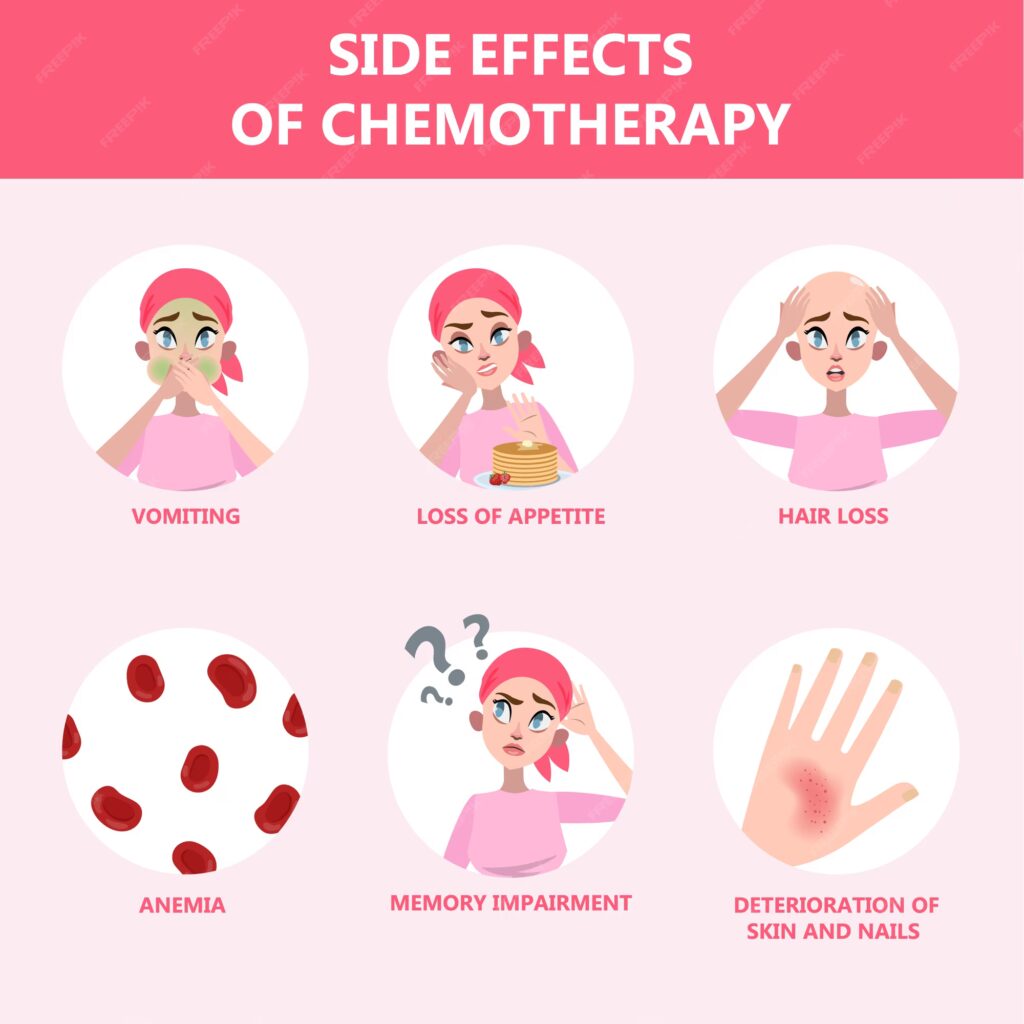

Nausea is one of the most distressing and common symptoms reported by women undergoing chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. It can begin within hours of receiving chemotherapy or arise days later, affecting appetite, hydration, and emotional wellbeing. Unlike short-lived queasiness from a stomach virus, cancer-related nausea can be deeply persistent and cyclic, especially in regimens involving platinum-based drugs.

In patients receiving combination therapy such as TCHP Chemotherapy, the emetic potential of agents like carboplatin, paclitaxel, and trastuzumab is notably high. These medications stimulate receptors in both the gastrointestinal tract and the brain’s chemoreceptor trigger zone, setting off a cascade of signals that provoke nausea and vomiting.

Importantly, the nausea experienced is not always tied to actual vomiting. Many women feel severe queasiness without being physically sick, which makes daily nutrition difficult and increases fatigue. This symptom significantly impairs quality of life and often leads patients to fear upcoming treatments.

The Mechanism Behind Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Its Relationship to Ovarian Cancer

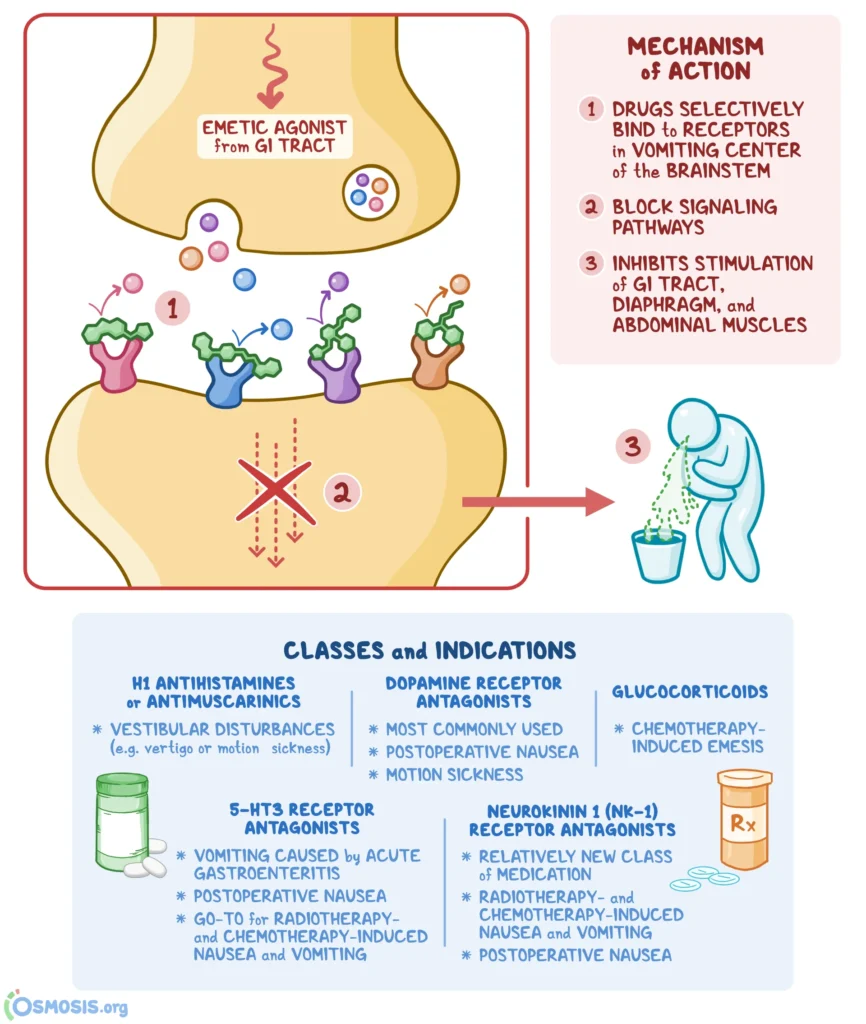

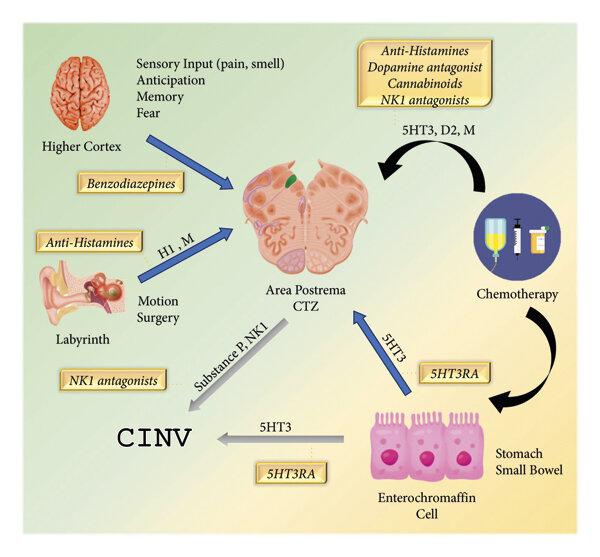

Nausea in the context of ovarian cancer chemotherapy is mediated by both central and peripheral pathways. On the central side, chemotherapy agents activate the area postrema in the brainstem—a region rich in serotonin and dopamine receptors that controls vomiting reflexes. On the peripheral side, damage to rapidly dividing cells in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract causes inflammation and delayed emptying of the stomach.

The relationship with ovarian cancer is also unique. Many patients already suffer from abdominal distension or ascites due to the tumor burden, which predisposes them to early satiety and nausea even before therapy begins. When chemotherapy is added, especially with platinum agents like cisplatin or carboplatin, the side effects compound.

The body’s inflammatory response plays a key role. Cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-alpha are elevated during chemotherapy, sensitizing both gut and brain pathways. Furthermore, patients undergoing radiologic evaluation such as Ovarian Cancer MRI often report procedural anxiety, which can exacerbate anticipatory nausea through classical conditioning—even before drugs are administered.

Prevalence of Chemotherapy-Related Nausea in Ovarian Cancer Cases

Studies show that up to 80% of women receiving chemotherapy for ovarian cancer report some form of nausea, with at least 40% experiencing it despite standard antiemetic medication. The incidence is higher in patients receiving regimens that include cisplatin or carboplatin, especially in high doses or combined with other emetogenic agents.

The table below outlines the frequency based on chemotherapy type:

| Chemotherapy Type | Incidence of Nausea (%) |

| High-dose cisplatin regimens | 90% |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel | 70–85% |

| TCHP chemotherapy | 75% |

| Targeted monotherapy | 25–35% |

Nausea tends to be more pronounced in the first 3 cycles and may taper off as the body acclimates—though in some, it worsens due to cumulative toxicity. Younger women and those with prior motion sickness or morning sickness during pregnancy are particularly susceptible.

What Causes Nausea in Ovarian Cancer Treatment: Beyond the Chemotherapy

While chemotherapy is the main trigger, there are several layers to nausea in ovarian cancer care. Understanding these helps target treatment more precisely.

Tumor-related causes include peritoneal irritation from widespread metastases, increased intra-abdominal pressure from ascites, and partial bowel obstruction—all common in late-stage cases. These mechanical and inflammatory stimuli contribute to baseline nausea even before chemotherapy begins.

Medication-related factors span beyond chemo drugs. Opioids for pain control often slow gastric motility. Antibiotics can disrupt the gut microbiome, leading to dysbiosis. Even multivitamins with iron can exacerbate nausea in sensitive patients.

Metabolic triggers include electrolyte imbalances such as low sodium or magnesium, which are common after prolonged vomiting or diarrhea. Elevated calcium levels due to bone metastases or paraneoplastic syndromes may also play a role.

Psychological contributors—like anticipatory nausea—are particularly strong in women who associate the hospital environment or IV lines with sickness. Even the smell of antiseptics or sight of a nurse can become conditioned triggers.

In later sections, we’ll explore which of these causes are reversible, which require immediate action, and how physicians distinguish between overlapping origins.

When Nausea Becomes an Emergency in Ovarian Cancer Care

Not all nausea in ovarian cancer treatment is benign. Some cases require urgent medical attention, especially when accompanied by red-flag symptoms. One key warning sign is persistent vomiting—inability to retain fluids for more than 24 hours—leading to dehydration, kidney strain, and hospitalization.

Another danger arises when nausea is accompanied by severe abdominal pain or bloating, suggesting possible bowel obstruction, a complication in advanced ovarian cancer. This is more likely when tumors infiltrate the bowel or when adhesions form after multiple surgeries.

The table below summarizes signs that warrant immediate evaluation:

| Symptom | Clinical Concern |

| Vomiting > 24 hours | Dehydration, electrolyte imbalance |

| Severe abdominal pain + nausea | Bowel obstruction |

| Nausea + confusion or weakness | Hypercalcemia, CNS metastases |

| New-onset nausea late in treatment | Disease progression, liver toxicity |

| Blood in vomit or dark coffee-ground emesis | GI bleeding |

In some rare cases, nausea may signal central nervous system involvement—especially if it’s paired with headaches, dizziness, or visual changes. This is more likely in metastatic disease and should be urgently assessed via imaging. These scenarios highlight the importance of not dismissing nausea as a routine side effect.

How Nausea Is Diagnosed and Monitored in Chemotherapy

The evaluation of nausea in ovarian cancer patients is multifactorial and often begins with clinical history. Oncologists inquire about timing (acute vs delayed), frequency, triggers, and severity. Tools like the MASCC Antiemesis Tool help quantify the patient’s symptom burden over time.

A physical examination may reveal signs of dehydration, abdominal distension, or bowel sounds suggestive of obstruction. Bloodwork is essential, especially serum electrolytes, renal function, calcium levels, and liver enzymes. When metabolic disturbances are suspected, correcting them may alleviate symptoms.

Imaging studies such as abdominal ultrasound or CT scans are used when obstruction, peritoneal spread, or liver dysfunction is suspected. In rare cases of refractory nausea with neurological signs, a brain MRI may be ordered to exclude CNS metastases.

Patients undergoing high-dose or multi-agent chemotherapy are often monitored using a cycle-based tracking chart to detect cumulative or anticipatory trends in nausea, enabling preemptive adjustment of medications in upcoming cycles.

Effective Treatments to Ease Nausea in Chemotherapy

Controlling chemotherapy-induced nausea requires a tailored approach. First-line treatment typically includes a combination of 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g., ondansetron) and dexamethasone, especially in the acute phase post-chemotherapy.

For delayed nausea (occurring >24 hours after treatment), NK1 receptor antagonists (e.g., aprepitant) are added to enhance efficacy. In TCHP Chemotherapy regimens, triplet antiemetic therapy is now standard to reduce patient distress.

Table: Common Antiemetics and Their Use

| Medication | Class | Best Used For |

| Ondansetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | Acute chemotherapy nausea |

| Aprepitant | NK1 receptor blocker | Delayed phase nausea |

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | Broad antiemetic support |

| Olanzapine | Antipsychotic | Refractory nausea |

| Metoclopramide | Dopamine antagonist | Gastroparesis, motility |

Adjunct therapies include acupressure wristbands, ginger supplements, and relaxation training, particularly for patients with anxiety-driven symptoms. In selected cases, opioid-sparing pain management helps reduce opioid-induced nausea.

Patients are also advised to eat small, bland meals and avoid strong odors post-treatment. Nutritional counseling can make a significant difference, especially when weight loss and anorexia are present—common in late-stage Pancreatic Cancer or symptoms of cancer that affect the digestive system.

Can Chemotherapy Nausea Be Prevented in Future Cycles?

Yes, and prevention is often more successful than treatment after symptoms begin. In modern oncology, preemptive antiemetic regimens are tailored to each cycle of chemotherapy, based on previous cycle response and drug emetogenicity.

Patients who develop anticipatory nausea benefit from behavioral therapy techniques and anxiolytic medications like lorazepam administered before infusion. In high-risk patients, antiemetics are started before chemotherapy and continued for several days afterward.

Lifestyle habits also play a role. Patients are encouraged to:

- Maintain hydration

- Avoid fatty or spicy foods before treatment

- Rest in an upright position after meals

- Minimize triggers such as strong odors or overheated rooms

Monitoring lab values is also preventive—keeping potassium, magnesium, and sodium levels stable can reduce nausea intensity. In integrative settings, guided imagery and breathing exercises are incorporated as part of the symptom control plan.

Will the Nausea Eventually Go Away?

Whether nausea resolves depends on multiple factors, including the specific chemotherapy protocol, patient sensitivity, overall cancer status, and individual metabolism. For many patients, nausea is temporary and fades within a few days post-infusion, especially when managed with a preemptive antiemetic plan.

In some chemotherapy regimens—particularly those used in TCHP Chemotherapy—patients report predictable timing of nausea, with it peaking on days 1–3 and then subsiding. In those cases, the nausea typically resolves completely between treatment cycles.

However, in patients with late-stage disease or complications such as peritoneal carcinomatosis, nausea may persist due to mechanical pressure, inflammation, or impaired bowel motility. When nausea is linked to metastases or gastrointestinal toxicity, it may become chronic or fluctuating.

Certain medications used in maintenance therapy, such as PARP inhibitors or targeted biologics, can also produce prolonged low-level nausea. But this is often manageable, and with proper dose adjustments or drug substitutions, the symptom may improve significantly.

The prognosis is best in cases where nausea is caused primarily by chemotherapy and not by disease burden. In these instances, the symptom often resolves entirely after chemotherapy ends, with no long-term consequences.

What Oncologists Say About Managing Nausea

Oncologists agree that nausea is one of the most feared side effects of chemotherapy, yet it is also one of the most controllable—when addressed early and proactively. According to Dr. Maya Desai, a clinical oncologist specializing in gynecologic cancers:

“The biggest mistake we see is patients underreporting nausea until it’s severe. We want them to speak up early so we can adjust their regimen and avoid compounding issues like dehydration or appetite loss.”

Experienced clinicians tailor antiemetic plans not just by drug protocol, but by individual history, such as prior pregnancy-related nausea or motion sickness. These factors can predict chemotherapy nausea intensity.

Additionally, oncologists emphasize that anticipatory nausea is real and should be treated with the same seriousness. Behavioral health specialists, nurse navigators, and dietitians are often included in the care team to create a multimodal nausea control plan.

From a clinical perspective, combination antiemetics, hydration support, and personalized counseling yield the best outcomes. Many teams also advise keeping a symptom journal between treatments to detect patterns and fine-tune medication timing.

15+ Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Nausea

1. What specific chemotherapy drugs am I receiving, and are they known to cause nausea?

Understanding the emetogenic potential of your regimen helps anticipate side effects.

2. What medications will I be given to prevent nausea before treatment?

Ask about both acute and delayed-phase antiemetics in your care plan.

3. Can I take anti-nausea medicine at home if symptoms start later?

Clarify which drugs you’ll be sent home with and when to take them.

4. Are there lifestyle changes I can make to reduce nausea between cycles?

Some changes in diet and routine can lessen symptoms significantly.

5. What should I do if I vomit more than once in 24 hours?

Know the warning signs of dehydration and when to call your team.

6. Could any of my current medications worsen nausea?

Opioids, antibiotics, and some supplements may exacerbate the issue.

7. Should I keep a symptom diary to help manage this?

Tracking patterns can help your doctor make evidence-based adjustments.

8. What should I eat—or avoid—on treatment days?

Some foods are more tolerable; your team may recommend a diet plan.

9. Will nausea get worse with each cycle, or stay about the same?

This depends on the type of chemo and your personal response.

10. What happens if nausea causes me to lose weight?

Malnutrition is a concern—ask about nutritional interventions.

11. Can I still receive treatment if my nausea is severe?

Sometimes, chemo is delayed or modified—your oncologist will decide.

12. Are there non-drug options to help me cope?

Acupuncture, ginger, and guided breathing may help in some cases.

13. Could nausea be a sign of something more serious?

Persistent or late-onset nausea may indicate complications.

14. When should I go to the ER for nausea or vomiting?

Know the threshold that requires emergency care.

15. Will nausea stop once chemotherapy is over?

In most cases, yes—but every patient’s timeline is different.