Mucocele Cancer Symptoms: Signs, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options

- What is a Mucocele?

- Common Causes and Predisposing Factors

- Recognizing Symptoms of Mucocele vs Mucocele Cancer

- Diagnostic Methods and Imaging Approaches

- Histological Features: Benign vs Malignant

- Treatment Options Based on Diagnosis and Stage

- Prognosis Based on Histological Type and Grade

- Monitoring After Treatment and Risk of Recurrence

- Potential Complications of Untreated Mucoceles

- Differences Between Mucocele and Other Oral Lesions

- Psychological and Quality of Life Considerations

- Pediatric vs Adult Presentations

- Role of Salivary Glands in Mucoceles and Their Cancerous Counterparts

- Surgical Considerations and Post-Excision Management

- Case Reports and Clinical Studies

- Prevention and Long-Term Oral Health Strategies

- Frequently Asked Questions

What is a Mucocele?

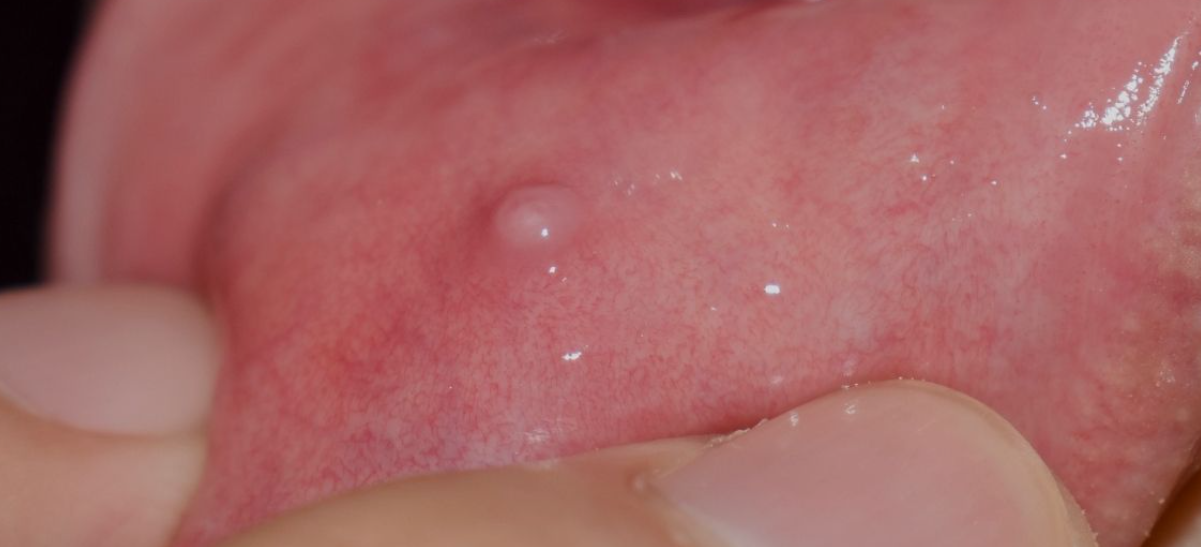

A mucocele is a fluid-filled lesion that co

mmonly forms in the oral cavity due to the disruption of minor salivary gland ducts. Most often, it appears on the inner surface of the lower lip but can also be found on the buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth (where it is referred to as a ranula), and even on the soft palate. These cysts develop when saliva leaks into the surrounding tissues rather than being properly channeled into the mouth. The resulting inflammation causes a localized swelling that may feel soft and movable to the touch. Despite being benign, a mucocele can cause functional or cosmetic issues depending on its size and location. Importantly, in rare cases or when left untreated for extended periods, a mucocele may undergo pathological changes that resemble or evolve into neoplastic growths, including low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Common Causes and Predisposing Factors

The formation of mucoceles is often triggered by mechanical trauma to the oral mucosa, such as repetitive lip biting, aggressive tooth brushing, or accidental injuries from dental appliances like braces. These actions can rupture the ducts of minor salivary glands, leading to mucus escape and pooling in the adjacent soft tissues. Another contributing factor includes the presence of chronic inflammation, such as gingivitis or poorly managed dental infections, which may stimulate excess mucus production or damage salivary tissue. Additionally, individuals with poor oral hygiene, recurrent herpes simplex infections, or systemic conditions affecting connective tissues are more susceptible to persistent or recurrent mucoceles. Although most mucoceles do not turn malignant, a small subset of patients, especially those over 40 or with a history of salivary gland neoplasms, should be monitored closely. This is particularly relevant because mucocele-like lesions can mimic the early appearance of salivary gland cancers, underscoring the need for accurate diagnosis through histopathology when the lesion is persistent.

Recognizing Symptoms of Mucocele vs Mucocele Cancer

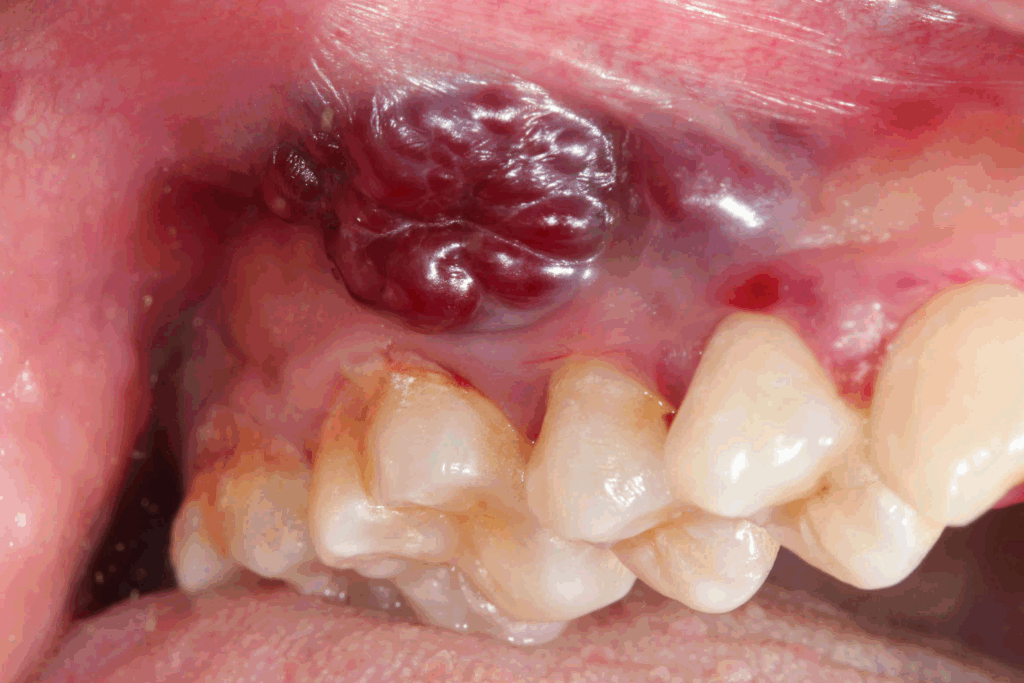

The symptoms of a mucocele typically include a dome-shaped bump inside the mouth that is soft, non-tender, and may have a bluish or translucent hue. In contrast, when a mucocele takes on potentially malignant characteristics, its presentation often changes significantly. Cancerous transformations tend to present as firm, rapidly enlarging masses that may ulcerate, bleed, or become painful. While benign mucoceles are often mobile and fluctuate in size, malignant lesions may become fixed to underlying tissues and show no signs of regression. Patients with cancerous developments may also notice referred pain in nearby areas, such as the ear or jaw, or experience difficulties in swallowing, speaking, or even breathing if the lesion is located near the oropharynx. Clinically, any lesion that fails to resolve within three to four weeks, shows signs of vascularization, or recurs after excision should be biopsied. It’s also worth noting that some low-grade cancers, like mucoepidermoid carcinoma, may initially mimic benign mucoceles, making vigilance during diagnosis crucial.

Diagnostic Methods and Imaging Approaches

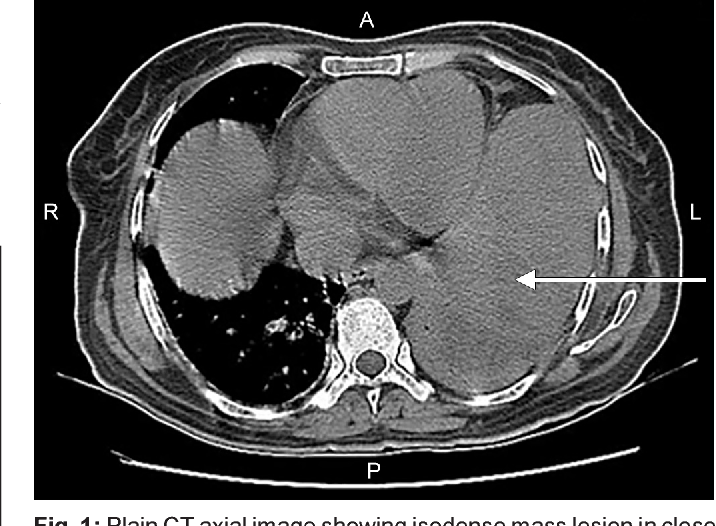

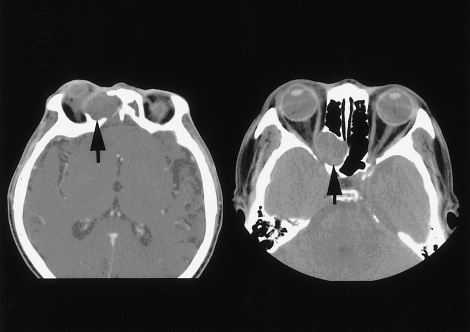

Diagnosis of mucocele cancer begins with a thorough physical examination and detailed patient history, focusing on lesion duration, recurrence, and associated symptoms such as pain or discharge. Palpation helps assess consistency, mobility, and tenderness, but imaging is essential for a more definitive assessment. High-resolution ultrasonography is often the first-line imaging modality as it can differentiate between fluid-filled and solid masses. Lesions suggestive of malignancy may show irregular borders, internal echoes, or vascularity. MRI offers superior soft tissue contrast and is particularly useful in evaluating larger or deep-seated mucoceles or when involvement of surrounding structures is suspected. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may be used to obtain cellular samples for preliminary evaluation, but incisional or excisional biopsy remains the gold standard. Histopathological analysis helps distinguish benign cysts from malignant tumors such as mucoepidermoid carcinoma, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, or acinic cell carcinoma. In some rare cases, where systemic involvement is suspected, PET-CT may be indicated to assess for metastasis. Understanding these diagnostics is vital—just as a DEXA scan might incidentally reveal bone changes suspicious for metastatic cancer, thorough imaging of oral lesions ensures no hidden malignancy is missed.

Histological Features: Benign vs Malignant

Histopathological evaluation is essential in distinguishing a benign mucocele from its malignant mimics. Under the microscope, a benign mucocele typically shows an accumulation of mucin surrounded by granulation tissue without an epithelial lining—this is classified as an extravasation type. In contrast, the retention type has an epithelial lining and results from ductal blockage rather than rupture. Malignant variants, particularly mucoepidermoid carcinoma, display cellular atypia, increased mitotic activity, and a mixture of mucous, epidermoid, and intermediate cells. The presence of perineural invasion, necrosis, and high-grade nuclear features indicates aggressive behavior. Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma, another potential diagnosis, presents with uniform nuclei but demonstrates infiltrative growth patterns and neurotropism. A careful pathological assessment ensures not only accurate diagnosis but also guides the treatment plan, especially when surgical margins must be evaluated. If the diagnosis is unclear, immunohistochemical staining (such as CK7, MUC5AC, and p63) can assist in further characterizing the neoplastic process.

Treatment Options Based on Diagnosis and Stage

The treatment plan for a mucocele or suspected mucocele cancer depends on the histological diagnosis and the clinical stage of the lesion. For simple mucoceles, minor surgical excision is often sufficient, followed by careful monitoring to avoid recurrence. In contrast, mucocele cancer requires a multidisciplinary approach involving maxillofacial surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists. Early-stage mucoepidermoid carcinoma may be treated effectively with wide local excision and clear margins. Radiation therapy is considered for high-grade tumors or those with close/involved margins. In advanced cases with lymph node involvement or distant spread, systemic chemotherapy may be necessary. Targeted therapies are under investigation but are not yet standard of care for these rare malignancies. Patients must be educated on the importance of follow-up care, as recurrence and metastasis, although rare, are possible even with complete resection.

Prognosis Based on Histological Type and Grade

| Histological Type | Grade | 5-Year Survival Rate | Risk of Recurrence | Common Treatment |

| Benign Mucocele | N/A | ~100% | Low | Excision only |

| Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma (Low) | Low-grade | 90–95% | Low | Surgical excision |

| Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma (Intermediate) | Intermediate | 70–85% | Moderate | Surgery ± Radiation |

| Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma (High) | High-grade | 30–50% | High | Surgery + Radiation + Chemotherapy |

| Polymorphous Low-Grade Adenocarcinoma | Low-grade | 90–98% | Low | Conservative surgery |

This table illustrates the stark contrast in outcomes between benign and malignant lesions. The grade of the tumor plays a pivotal role in prognosis and recurrence risk. Regular follow-up and imaging are key components in the management of high-grade malignancies.

Monitoring After Treatment and Risk of Recurrence

Post-treatment surveillance is vital in managing both benign mucoceles and their malignant counterparts. For benign cases, the risk of recurrence is generally associated with incomplete excision or continued trauma to the affected area. Patients should be advised to avoid habits such as lip or cheek biting and to maintain optimal oral hygiene. In malignant cases, follow-up involves periodic imaging, physical examination, and, in some instances, repeat biopsies if suspicious lesions reappear. Surveillance schedules typically include check-ups every 3–6 months during the first two years, with extended intervals afterward. Long-term vigilance is particularly important for high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma and polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma due to their potential for late recurrence. It’s worth noting that individuals with a history of unfavorable intermediate risk prostate cancer may face compounded risks if systemic immunosuppression or radiotherapy has impacted their oral mucosa, making thorough monitoring even more essential.

Potential Complications of Untreated Mucoceles

When left untreated, mucoceles can lead to several complications depending on their size, duration, and location. In many cases, an untreated mucocele may rupture spontaneously and recur multiple times, often becoming larger or more fibrotic with each episode. These recurrent lesions can lead to chronic inflammation and scarring of the underlying salivary tissue, which may interfere with gland function. In mucoceles on the floor of the mouth (ranulas), growth can become significant enough to displace the tongue, causing speech or swallowing difficulties. Rarely, a neglected or misdiagnosed lesion may harbor or transform into a malignant growth, especially in older adults or individuals with immune suppression. Delay in intervention not only complicates the excision procedure but also increases the risk of nerve involvement, particularly in lesions near the lingual or mental nerves. Continuous oversight and a proactive treatment strategy are the best means to prevent such adverse outcomes. Just as Sermorelin-related hormonal imbalances may mask early symptoms of certain cancers, overlooking minor oral swellings could lead to missed or delayed cancer diagnoses.

Differences Between Mucocele and Other Oral Lesions

It is essential to differentiate mucoceles from a variety of other lesions that can appear in the oral cavity. For example, fibromas, which are benign fibrous tissue overgrowths due to chronic irritation, can present as firm, painless nodules similar in size to mucoceles. Pyogenic granulomas may mimic mucoceles in color and size but are usually highly vascular, bleed easily, and appear rapidly. Oral mucosal melanoma is another rare but critical differential, particularly in pigmented or unusually dark lesions. Moreover, minor salivary gland tumors, both benign (like pleomorphic adenoma) and malignant (such as adenoid cystic carcinoma), often resemble mucoceles clinically but require very different management approaches. Diagnosis becomes particularly challenging in cases where a mucocele-like lesion is located in an uncommon site, such as the palate or retromolar area. Therefore, any lesion that behaves atypically or persists longer than 2–3 weeks should be biopsied. A collaborative approach involving dental professionals, oral surgeons, and pathologists ensures accurate identification and avoids overtreatment or dangerous delays in therapy.

Psychological and Quality of Life Considerations

Although mucoceles are often regarded as minor lesions, their impact on quality of life can be significant, especially when located in visible areas or when recurrence interferes with daily function. Patients may experience anxiety about the possibility of malignancy, especially if they’ve had a prior history of cancer or are undergoing treatment for other serious illnesses. The cosmetic effect of repeated mucoceles on the lip or cheek, especially in adolescents or young adults, can also lead to self-consciousness or avoidance of social interaction. In cases where surgical excision is performed, scarring or sensory changes (e.g., numbness, tingling) can contribute to persistent discomfort or psychological distress. Additionally, patients may struggle with the dietary and speech restrictions imposed by large or recurrent lesions. Counseling, patient education, and open communication with healthcare providers can mitigate these concerns. Even a discussion about how a DEXA scan may identify unrelated but suspicious bone lesions can help normalize thorough diagnostic workups and reduce fear surrounding more extensive testing.

Pediatric vs Adult Presentations

Mucoceles can occur in both pediatric and adult populations, but there are notable differences in presentation, cause, and management. In children and adolescents, mucoceles are most frequently due to repetitive trauma, such as lip biting or accidental falls. These lesions are usually superficial, fluctuate in size, and often recur due to unintentional re-injury. Behavioral modification and parental education are crucial components of treatment in young patients. In contrast, adults tend to present with deeper lesions or ranulas, especially in the floor of the mouth. In older individuals, there’s also an increased risk of underlying neoplasms, particularly when the lesion is firm, fixed, or associated with other signs such as paresthesia or weight loss. Adults are more likely to require imaging or biopsy to rule out malignancy. Another consideration is comorbidities: systemic illnesses or medications may influence lesion development and healing, necessitating a more cautious treatment plan. Age-specific factors thus play a significant role in both diagnosis and therapeutic approach.

Role of Salivary Glands in Mucoceles and Their Cancerous Counterparts

The development of mucoceles is closely tied to the function and structure of the minor salivary glands. These glands are responsible for producing mucous secretions that help lubricate the oral cavity, protect against bacteria, and facilitate speech and swallowing. When the ducts of these glands are injured or obstructed, mucus accumulates, resulting in cystic swelling. In benign mucoceles, this disruption is usually mechanical and self-limited. However, salivary glands are also a common site for both benign and malignant tumors, with the minor glands contributing to approximately 22% of salivary gland neoplasms. Malignant transformation, while rare, may arise directly from glandular tissue or evolve from a long-standing lesion that mimics a mucocele. Tumors like mucoepidermoid carcinoma or adenocarcinoma can initially appear as small, non-specific lumps. Recognizing subtle changes—such as increasing firmness, irregular borders, or ulceration—is vital in differentiating a true mucocele from its neoplastic imitators.

Surgical Considerations and Post-Excision Management

Surgical excision remains the gold standard for both diagnostic clarification and therapeutic resolution of persistent mucoceles or suspected mucocele cancers. For simple mucoceles, a conservative approach with complete removal of the lesion and surrounding glandular tissue is usually curative. Surgeons must take care to avoid damaging nearby neurovascular structures, especially in anatomically complex areas such as the floor of the mouth. In malignant cases, the procedure is more involved, requiring wide local excision with histologically negative margins. If high-grade pathology is confirmed, adjunctive radiation therapy may follow. After surgery, patients should be monitored for signs of infection, hematoma, or recurrence. Regular follow-ups typically include clinical exams and, when warranted, imaging to rule out deeper residual disease. Patient compliance with post-operative care, including wound hygiene and avoidance of trauma to the surgical site, plays a significant role in long-term success.

Case Reports and Clinical Studies

Multiple published case reports and retrospective studies have highlighted the importance of differentiating mucoceles from malignancies. For instance, a 2019 case series described patients initially diagnosed with mucoceles who were later found to have low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma upon biopsy. These cases emphasize the necessity of histopathologic confirmation in all lesions persisting longer than 4 weeks or recurring after surgical intervention. Studies have also evaluated imaging patterns on ultrasound and MRI, revealing that high-grade tumors often present with ill-defined margins and heterogeneous internal structures. Epidemiologic data show a higher prevalence of malignant mucocele-like lesions in individuals over 50, smokers, and those with prior exposure to radiation. This supports the approach of cautious assessment, especially in older patients. It’s also worth noting that certain oncologic risk profiles, such as unfavorable intermediate risk prostate cancer, may co-occur with other malignancies, suggesting the need for broader oncologic vigilance in at-risk populations.

Prevention and Long-Term Oral Health Strategies

Preventing mucoceles and their complications involves maintaining good oral hygiene, minimizing trauma, and seeking early medical attention for unusual lesions. Educating patients—especially children and adolescents—on avoiding behaviors like lip biting or chewing on pens can reduce the incidence of mucoceles. Dental professionals should examine the oral cavity thoroughly during routine visits, especially in patients with dentures, braces, or known mucosal fragility. When a mucocele is excised, it is important to analyze the specimen to confirm the diagnosis, thus reducing the chance of missing early-stage cancer. For those with a history of salivary gland tumors or systemic cancer, regular screenings and imaging may be indicated. Consistent hydration and the use of protective mouthguards during sports or nighttime grinding can also help reduce trauma-related risk. These small measures collectively enhance oral resilience and reduce the probability of recurrence or malignant transformation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a mucocele and a salivary gland tumor?

A mucocele is a benign cyst formed due to mucus accumulation from ruptured or blocked salivary ducts, whereas a salivary gland tumor can be either benign or malignant and involves abnormal cell growth within the glandular tissue itself. Unlike mucoceles, tumors often display persistent growth, may be painful, and can invade nearby structures.

Can a mucocele become cancerous?

While mucoceles themselves are not cancerous, they can sometimes resemble or obscure early-stage salivary gland cancers, especially if persistent, recurrent, or located in high-risk areas like the palate or floor of the mouth. Histological examination is essential to rule out malignancy.

What are the signs that a mucocele might be cancerous?

Signs that warrant concern include rapid growth, firmness, ulceration, pain, bleeding, or fixation to underlying tissues. Any lesion that doesn’t resolve within 3–4 weeks or recurs after excision should be evaluated for malignancy through biopsy.

How is mucocele cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves clinical evaluation, imaging (ultrasound, MRI), and most importantly, histological confirmation through biopsy. Features such as cell atypia, mitotic activity, and tissue invasion help pathologists determine malignancy.

Can children get mucocele cancer?

Mucocele cancer is exceedingly rare in children. Most pediatric mucoceles are benign and trauma-induced. However, persistent or atypical lesions in children should still be biopsied to rule out rare congenital or neoplastic conditions.

How quickly does mucocele cancer progress?

The progression rate depends on the histologic type and grade of the tumor. Low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinomas may grow slowly and remain localized for months, whereas high-grade variants can be aggressive and metastasize rapidly without timely intervention.

Does removal of a mucocele eliminate cancer risk?

Can mucoceles return after surgery?

Yes, mucoceles can recur, especially if the involved salivary gland is not completely removed or if the patient continues habits like lip biting. In cases of mucocele cancer, recurrence may also indicate incomplete resection or aggressive tumor biology.

Is there a non-surgical way to treat mucoceles?

Small mucoceles may resolve spontaneously, especially in children. Some physicians attempt corticosteroid injections or laser ablation, but these are generally less effective than surgical excision and not suitable if cancer is suspected.

What type of doctor should I see for a mucocele?

Dentists or oral surgeons are typically the first to evaluate mucoceles. If cancer is suspected, referral to a head and neck oncologist or maxillofacial surgeon is appropriate for further workup and management.

Are mucoceles painful?

Most mucoceles are painless. However, if they become large, ulcerated, or infected, they can cause discomfort. Cancerous lesions, in contrast, are more likely to be painful or associated with nerve symptoms.

Do mucoceles bleed?

Benign mucoceles rarely bleed unless traumatized. If spontaneous bleeding occurs, especially without clear trauma, it could be a warning sign of malignancy and warrants immediate medical evaluation.

Can poor oral hygiene cause mucocele cancer?

Poor hygiene alone doesn’t cause mucocele cancer, but it can contribute to chronic irritation and infection, increasing the likelihood of persistent lesions. Persistent inflammation is a recognized risk factor for various oral malignancies.

How long does it take to heal after mucocele surgery?

Healing typically takes 1–2 weeks for minor mucoceles. For deeper or malignant lesions, healing may take longer, especially if radiation or chemotherapy is involved post-surgery. Pain, swelling, and scar formation are generally minimal with proper care.

Are follow-up visits necessary after mucocele treatment?

Yes, follow-up is important to monitor for recurrence, confirm complete healing, and rule out missed pathology. For benign mucoceles, one or two follow-ups may suffice, while cancer cases require a structured, long-term surveillance plan.