Intestinal Cancer in Cats: A Comprehensive Guide

- Understanding Intestinal Cancer in Cats

- Recognizing the Symptoms

- Diagnostic Procedures

- Treatment Options and Prognosis

- The Biology of Intestinal Tumors in Cats

- Challenges in Early Detection and Misdiagnosis

- Nutritional Management and Supportive Care

- Surgical Options and Postoperative Care

- Treatment Protocols: Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Supportive Care

- Monitoring and Follow-Up During and After Treatment

- Nutritional Adjustments for Cats with Intestinal Cancer

- Impact of Cancer on Quality of Life and Behavior

- Prognosis Based on Cancer Type, Grade, and Treatment Response

- When to Euthanize a Cat with Intestinal Cancer

- Emotional Support for Pet Owners

- Preventive Strategies and Early Detection Tips

- Frequently Asked Questions

Understanding Intestinal Cancer in Cats

Intestinal cancer in cats encompasses various malignant tumors affecting the gastrointestinal tract, including the small and large intestines. The most common types are lymphoma and adenocarcinoma. Lymphoma, particularly the alimentary form, is prevalent and can be associated with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) infection. Adenocarcinoma, though less common, is aggressive and often leads to obstruction or perforation of the intestines. These cancers are more frequently diagnosed in older cats, typically over six years of age.

The exact causes of intestinal cancer in cats remain unclear, but factors such as chronic inflammation, genetic predisposition, and viral infections like FeLV and feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) may contribute. Understanding the nature of these cancers is crucial for early detection and management.

Recognizing the Symptoms

Early signs of intestinal cancer in cats can be subtle and easily mistaken for less serious gastrointestinal issues. Common symptoms include:

- Persistent vomiting

- Chronic diarrhea

- Weight loss despite normal appetite

- Loss of appetite

- Lethargy

- Abdominal discomfort or distension

- Blood in stool

These symptoms often develop gradually, making it essential for cat owners to monitor any changes in their pet’s behavior or health closely. If such signs persist, prompt veterinary consultation is advised.

Diagnostic Procedures

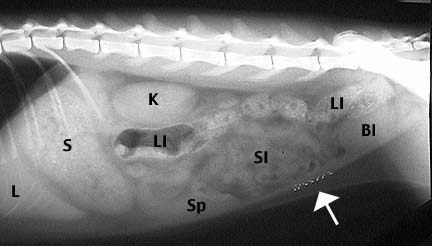

Diagnosing intestinal cancer involves a combination of clinical evaluation and diagnostic testing. Veterinarians typically begin with a thorough physical examination, followed by blood tests to assess overall health and detect any abnormalities. Imaging techniques such as abdominal ultrasound and radiographs are employed to visualize the intestines and identify masses or thickening. Definitive diagnosis often requires tissue sampling through fine-needle aspiration or biopsy, which allows for histopathological examination to determine the cancer type and grade.

In some cases, advanced imaging like CT scans may be utilized for detailed assessment, especially if surgical intervention is considered. Accurate diagnosis is vital for developing an effective treatment plan and providing a prognosis.

Treatment Options and Prognosis

Treatment strategies for intestinal cancer in cats depend on the cancer type, location, and stage at diagnosis. For localized tumors like adenocarcinomas, surgical removal of the affected intestinal segment may be pursued, often followed by chemotherapy to address potential metastasis. Lymphomas are typically managed with chemotherapy protocols, as they are usually diffuse and not amenable to surgery.

The prognosis varies based on several factors. Cats with small-cell lymphoma may respond well to chemotherapy, achieving remission and extended survival times. Conversely, those with high-grade lymphomas or adenocarcinomas often have a poorer prognosis, with survival times ranging from a few months to a year, depending on treatment response and disease progression. Early detection and intervention are key to improving outcomes.

The Biology of Intestinal Tumors in Cats

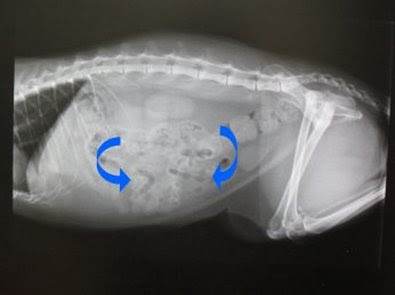

Understanding the cellular and anatomical behavior of feline intestinal tumors helps explain why early detection is so difficult and why some treatments are more effective than others. Lymphoma, the most common intestinal cancer in cats, originates from lymphocytes—white blood cells involved in immune defense. In its small-cell form, the lymphoma infiltrates the intestinal wall diffusely, leading to gradual thickening without forming distinct masses. This often results in subtle symptoms like weight loss and intermittent vomiting over several months.

High-grade lymphoma, however, is more aggressive and tends to form nodular lesions, sometimes leading to intestinal obstruction or rupture. Adenocarcinoma arises from the epithelial cells lining the intestine. It tends to be more locally invasive, forming solid tumors that may ulcerate or metastasize to lymph nodes and liver. The differences in cell origin and growth patterns dictate not only how the disease is diagnosed but also which treatments are viable. While lymphomas typically respond to systemic chemotherapy, adenocarcinomas require localized intervention and carry a higher surgical risk.

Challenges in Early Detection and Misdiagnosis

Feline intestinal cancer is notorious for evading early detection due to the non-specific nature of its symptoms. Vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss are common to many less serious gastrointestinal issues, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), food allergies, parasitic infections, or pancreatitis. Without thorough diagnostics, these cases can be misclassified and treated symptomatically with steroids or dietary changes—often with temporary improvement, which masks the underlying malignancy.

The delay in appropriate diagnostics can allow the tumor to advance unchecked. By the time a biopsy is performed, the disease may have progressed significantly, reducing the effectiveness of available treatments. Some clinicians recommend full-thickness intestinal biopsies early in the diagnostic process, particularly when gastrointestinal symptoms persist beyond 2–4 weeks despite standard management. Owners are encouraged to advocate for advanced imaging or referral to a specialist when their cat’s health does not improve with routine care. A similar diagnostic delay is seen in canine cases where dietary factors, like excessive beef consumption, can mimic or mask early warning signs of inflammatory or neoplastic diseases.

Nutritional Management and Supportive Care

Cats undergoing treatment for intestinal cancer often require special nutritional strategies to maintain weight, energy levels, and immune function. Malnutrition is common due to decreased appetite, malabsorption, and nausea from chemotherapy. A high-protein, easily digestible diet enriched with omega-3 fatty acids may help preserve muscle mass and reduce inflammation. Veterinary prescription diets are available that support gastrointestinal function and minimize digestive stress. In some cases, appetite stimulants or anti-nausea medications are prescribed to support feeding.

Hydration is critical. Cats with intestinal cancer often suffer from fluid loss through vomiting or diarrhea, leading to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Subcutaneous fluids or intravenous support may be necessary, especially during intensive treatment phases. Probiotic supplementation is also considered beneficial, as chemotherapy can disrupt the normal intestinal microbiome. Proper nutritional support not only improves quality of life but also enhances the effectiveness of medical therapy by supporting organ function and treatment tolerance.

Surgical Options and Postoperative Care

Surgical intervention may be viable for localized tumors such as adenocarcinomas or obstructive lymphomas. The procedure involves removing the affected intestinal segment and reconnecting the healthy ends in a process called anastomosis. Surgery is usually followed by a recovery period where the cat is monitored for signs of leakage, infection, or recurrence. In high-risk cases, biopsies of adjacent tissues and lymph nodes are taken during surgery to assess metastatic spread.

Postoperative care includes pain management, gastrointestinal rest (often with IV fluids and no food for 12–24 hours), and then a gradual reintroduction of soft, easily digestible food. Antibiotics and anti-inflammatory medications may also be used depending on the level of intestinal invasion. Cats that recover well from surgery and have clean margins—meaning no residual cancer cells at the cut edges—may enjoy significantly improved prognosis, particularly if follow-up chemotherapy is administered to address microscopic disease. However, outcomes vary widely depending on tumor type, size, location, and whether metastasis has already occurred at the time of diagnosis.

Treatment Protocols: Chemotherapy, Surgery, and Supportive Care

Treatment for feline intestinal cancer typically involves a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and supportive care. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for localized, resectable tumors such as adenocarcinomas or leiomyosarcomas. The procedure involves removing the affected intestinal segment along with margins of healthy tissue and nearby lymph nodes. Post-operative recovery varies but usually requires hospitalization, analgesia, and careful monitoring of gastrointestinal function.

Chemotherapy is the mainstay for lymphomas, particularly diffuse or high-grade forms. Protocols often include medications like chlorambucil and prednisone for small-cell lymphoma, or multi-agent regimens (CHOP protocols) for high-grade types. Response rates vary, but small-cell lymphoma often enters remission with oral chemotherapy, allowing for outpatient treatment and good quality of life.

Supportive care is essential across all treatment types. Nutritional support, hydration, antiemetics, appetite stimulants, and probiotics are commonly used. In advanced or inoperable cases, palliative care focusing on comfort and appetite preservation may be the most humane approach. Owners must be involved in daily monitoring and follow-up, as early recognition of side effects or relapse can make a critical difference in outcomes.

Monitoring and Follow-Up During and After Treatment

Once treatment begins, cats with intestinal cancer require regular monitoring to evaluate the efficacy of therapy and manage side effects. Blood tests are performed frequently to assess white blood cell counts, liver and kidney function, and anemia. Imaging—typically ultrasound—is used periodically to detect recurrence or progression. For cats on oral chemotherapy, owners must be educated to watch for signs of drug toxicity such as inappetence, vomiting, or increased lethargy.

Post-surgical patients need close monitoring for gastrointestinal transit recovery, incision site healing, and nutritional adequacy. Cats with small-cell lymphoma in remission can be maintained on long-term low-dose chemotherapy with good quality of life, but periodic reevaluation is necessary. Even when clinical signs are controlled, microscopic disease may persist, requiring ongoing management. Like human patients recovering from diseases that can resurface as cutaneous lesions—such as in breast cancer spread to skin—monitoring must include attention to subtle clinical changes that may signal relapse.

Nutritional Adjustments for Cats with Intestinal Cancer

Nutrition plays a vital role in supporting cats undergoing cancer treatment. The goal is to maintain lean body mass, support immune function, and reduce inflammation. Diets high in easily digestible proteins and moderate in fat are often recommended. Highly processed commercial foods may be poorly tolerated, especially if they contain low-quality protein sources, dyes, or synthetic preservatives. Homemade or prescription veterinary diets designed for gastrointestinal sensitivity are often used, depending on the cat’s tolerance.

In some cases, feeding tubes (esophagostomy or nasogastric) may be placed if oral intake becomes insufficient due to nausea, oral ulcers, or anorexia. High-calorie recovery diets formulated for cats can be used to ensure sufficient energy intake. Supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA), which have anti-inflammatory properties and may slow tumor progression, is often recommended. Appetite stimulants like mirtazapine or capromorelin are used if intake remains low despite nutritional support. Hydration should be maintained with subcutaneous fluids if needed, especially in cats prone to dehydration or chemotherapy-induced vomiting.

Impact of Cancer on Quality of Life and Behavior

Intestinal cancer can profoundly affect a cat’s quality of life and emotional well-being. As the disease progresses, cats may become withdrawn, hide more frequently, or avoid physical contact. Litter box habits may change due to abdominal discomfort, and previously social cats may become irritable or lethargic. Pain, nausea, and weakness reduce engagement with play, grooming, or exploration. Owners may observe that their cat no longer seeks warmth, stops jumping to high places, or isolates from family members.

These behavioral shifts are not just signs of physical decline but indicators of emotional and neurological distress. Tracking these subtle changes is essential for making timely decisions about adjusting treatment or introducing palliative care. Regular quality-of-life assessments, conducted using scales that evaluate appetite, hydration, mobility, and social behavior, can help guide these decisions. The goal of therapy should always include preservation of dignity, comfort, and interaction—elements that define a cat’s perceived well-being.

Prognosis Based on Cancer Type, Grade, and Treatment Response

| Cancer Type | Grade | Common Treatment | Median Survival Time | Treatment Response |

| Small-cell Lymphoma | Low-grade | Oral chemotherapy | 1.5–3 years | Often good, with long remission |

| High-grade Lymphoma | High-grade | CHOP-based chemotherapy | 3–9 months | Variable, more aggressive |

| Adenocarcinoma | Variable | Surgery + chemotherapy | 2–6 months | Poor if metastasized |

| Leiomyosarcoma | Moderate | Surgery | 6–18 months | Good if fully resected |

| Mast Cell Tumor (GI) | High-grade | Surgery ± chemotherapy | 1–4 months | Often guarded to poor |

This table helps visualize how prognosis varies significantly depending on tumor biology, grade, and therapeutic strategy. While some cancers like small-cell lymphoma respond favorably to long-term management, others like adenocarcinoma or GI mast cell tumors carry a much poorer outlook, especially when diagnosed late or when metastasis has occurred.

When to Euthanize a Cat with Intestinal Cancer

One of the most difficult questions for cat owners is knowing when to consider euthanasia. This decision is deeply personal but should be based on objective indicators of quality of life, medical progression, and comfort. When a cat no longer responds to treatment, has persistent pain, refuses food and water for more than 2–3 days, or experiences unmanageable vomiting, diarrhea, or labored breathing, humane euthanasia becomes a compassionate choice.

Some signs are more subtle: hiding behavior, lack of interest in surroundings, or inability to rest comfortably. These may suggest suffering even if clinical values look stable. Consulting with your veterinarian to perform a structured quality-of-life assessment—rating appetite, hydration, mobility, and social engagement—can offer clarity. Owners should not feel guilt over choosing to prevent further decline; a peaceful, pain-free goodbye may be the final act of love. This emotional decision, similar to the nuanced approach needed in complex, slow-progressing conditions like Mucocele cancer symptoms, should be guided by both medical facts and emotional understanding.

Emotional Support for Pet Owners

A diagnosis of intestinal cancer in a beloved cat is emotionally devastating. Grief, guilt, confusion, and helplessness are common emotions experienced by owners navigating this journey. Whether pursuing aggressive treatment or palliative care, pet guardians often feel overwhelmed by frequent vet visits, medication management, and observing their cat’s decline. Support systems are essential—not just for the cat, but for the humans providing care.

Speaking openly with veterinarians about prognosis, pain management, and expectations can ease some of the uncertainty. Support groups, whether in person or online, provide a space to share experiences, find validation, and learn coping strategies. Pet loss hotlines and veterinary social workers can offer guidance during anticipatory grief and post-loss bereavement. Taking time to celebrate moments of joy, documenting memories, and creating rituals of farewell can help preserve the bond during difficult times and bring emotional closure when the time comes.

Preventive Strategies and Early Detection Tips

Although not all cases of intestinal cancer in cats can be prevented, certain strategies may reduce the risk or enable earlier diagnosis. Routine veterinary checkups with abdominal palpation, bloodwork, and monitoring of weight changes are fundamental. For older cats or those with chronic GI symptoms, early imaging (such as ultrasound) can detect subtle abnormalities before symptoms become severe. Nutritional support, including high-quality, anti-inflammatory diets, may help reduce chronic gut irritation, which in some cases may precede neoplastic changes.

Cats with a history of FeLV or FIV should be monitored more closely due to their increased cancer risk. Owners should also keep a health diary—tracking appetite, stool quality, energy, and behavior—as even mild changes can precede clinical illness. Educating oneself about warning signs and knowing when to escalate care can significantly influence outcomes. Prevention in this context doesn’t mean eliminating risk, but rather staying one step ahead through vigilance, awareness, and proactive care.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is intestinal cancer in cats?

Intestinal cancer in cats refers to the presence of malignant tumors in the gastrointestinal tract, commonly involving the small intestine, large intestine, or surrounding lymphatic tissues. The most prevalent types are lymphoma and adenocarcinoma, though other rarer tumors may occur. These cancers can interfere with digestion, nutrient absorption, and immune regulation, leading to serious systemic effects.

What are the early symptoms of intestinal cancer in cats?

Early symptoms are often vague and may mimic common gastrointestinal problems. These include chronic vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, lethargy, reduced appetite, and changes in stool consistency or color. Over time, symptoms become more persistent and severe, making early detection through veterinary exams essential.

Is intestinal cancer in cats treatable?

Yes, some forms of intestinal cancer, especially small-cell lymphoma, can be managed effectively with chemotherapy, allowing for months or even years of quality life. Surgery is also an option for localized tumors. However, treatment outcomes depend on the cancer type, grade, location, and how early it is diagnosed.

What causes intestinal cancer in cats?

There is no single known cause. However, risk factors include age, chronic inflammation of the gut, viral infections such as feline leukemia virus (FeLV), genetic predisposition, and possibly long-term exposure to low-quality diets or environmental toxins. Often, it results from a combination of these factors over time.

How is intestinal cancer diagnosed in cats?

Diagnosis typically involves a physical exam, blood tests, abdominal ultrasound, and sometimes x-rays or CT scans. A definitive diagnosis requires a biopsy or fine-needle aspiration of the intestinal tissue to identify the tumor type under a microscope. This helps guide treatment decisions.

Can intestinal cancer in cats be mistaken for IBD?

Yes, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and intestinal lymphoma can present with very similar symptoms. In fact, low-grade lymphoma may initially respond to the same medications used for IBD. Only histopathological analysis can definitively distinguish between the two, which is why biopsy is so important.

What is the prognosis for cats with intestinal cancer?

Prognosis varies. Cats with small-cell lymphoma treated with oral chemotherapy may live 1.5 to 3 years or more. High-grade tumors or adenocarcinomas tend to have shorter survival times, typically 2 to 6 months, even with treatment. Early detection and response to therapy are the biggest prognostic factors.

Should I change my cat’s diet after diagnosis?

Yes, dietary modifications often help maintain strength and reduce digestive distress. Easily digestible, high-protein, low-residue diets are usually recommended. Some cats benefit from added omega-3 fatty acids or prescription gastrointestinal diets. Your vet can help formulate a tailored nutrition plan.

Is surgery always necessary?

Not always. Surgery is considered when there’s a solitary, resectable mass, as in many adenocarcinomas. In cases of diffuse lymphoma, chemotherapy is more appropriate. If cancer has already spread or the cat is medically fragile, surgery may not be a viable option, and palliative care becomes the focus.

Can cats tolerate chemotherapy well?

Generally, yes. Cats often experience fewer and milder side effects from chemotherapy than humans or dogs. Most tolerate oral or injectable chemotherapy well, with manageable side effects like mild nausea, temporary appetite loss, or fatigue. Routine monitoring is required throughout treatment.

What if my cat stops eating during treatment?

Loss of appetite is common in feline cancer, especially during chemotherapy. This may be managed with appetite stimulants, anti-nausea medications, and high-calorie supplements. In severe cases, feeding tubes may be considered to ensure nutritional intake and support recovery.

How do I know if the treatment is working?

Your veterinarian will monitor clinical signs, body weight, blood tests, and imaging results over time. Reduction in vomiting or diarrhea, stabilization of weight, improved appetite, and more energy are all good signs. For some tumors, serial ultrasounds help evaluate physical tumor size.

When is it time to consider euthanasia?

When your cat no longer responds to treatment, refuses food, suffers from persistent pain, or becomes withdrawn and unresponsive, humane euthanasia may be the kindest option. Regular quality-of-life assessments help guide this decision, ensuring comfort and dignity are prioritized.

Can intestinal cancer recur after treatment?

Yes, recurrence is possible, particularly with high-grade tumors. Even in remission, microscopic cancer cells may remain. Regular follow-ups and repeat imaging help catch recurrence early. In some cases, a second round of treatment may be possible, depending on the cat’s health.

How can I support my cat emotionally during this time?

Keep routines predictable, offer frequent gentle interactions, and provide a quiet, warm space for rest. Monitor behavior closely and celebrate small moments of joy. Emotional connection plays a major role in maintaining quality of life, even as physical health declines.