How Fast Does Oral Cancer Spread? Signs & What to Expect

- Foreword

- 1. Understanding Oral Cancer

- 2. Progression and Spread of Oral Cancer

- 3. Risk Factors Influencing Spread

- 4. Symptoms and Early Detection

- 5. Treatment Options

- 6. Prognosis and Survival Rates

- 7. Prevention and Risk Reduction

- 8. Emerging Research and Future Directions

- 9. Patient Stories and Testimonials

- 10. Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

When you hear the term “oral cancer,” what exactly comes to mind?

For many people, it’s a vague, uncomfortable phrase that hovers somewhere between “something my dentist screens for” and “a rare disease I probably don’t have to worry about.” But here’s the truth: oral cancer is more common — and more complex — than most people realize. And if you’re reading this article, chances are you already suspect that it’s worth knowing more than just the basics.

Let’s unpack it thoroughly, starting from square one.

What Is Oral Cancer?

Oral cancer refers to malignant (i.e., cancerous) growths that occur in or around the mouth. Medically, it falls under the broader category of head and neck cancers, but it specifically affects the oral cavity — think lips, tongue, inner cheeks, gums, floor and roof of the mouth, and even the oropharynx (the middle part of the throat, right behind the mouth).

You might be wondering: “Are there different types of oral cancer?” Yes, and the most common by far — over 90% of all oral cancer cases — is squamous cell carcinoma. This type originates in the flat, thin cells lining the inside of your mouth and throat. Squamous cells are like nature’s wallpaper: functional, but susceptible to wear, injury, and — in the wrong conditions — malignant transformation.

There are rarer subtypes too: salivary gland carcinomas, lymphomas, melanomas, and even sarcomas. Each behaves differently, and each has a distinct treatment path. But for the purposes of this article — particularly the question of how fast oral cancer spreads — squamous cell carcinoma will be our primary focus.

Where Does Oral Cancer Usually Develop?

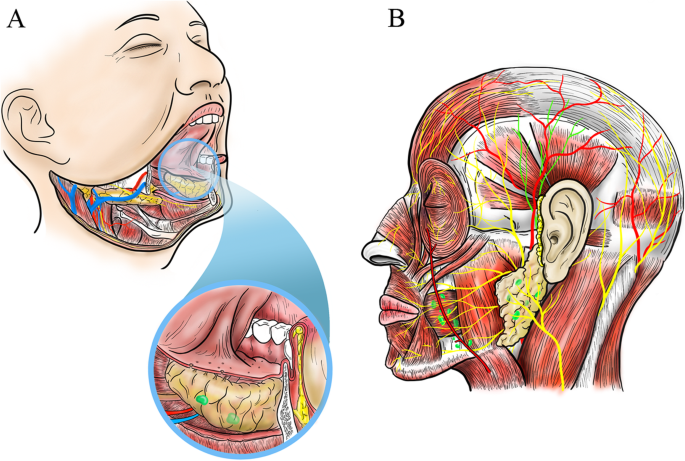

The mouth may look small from the outside, but anatomically, it’s a pretty intricate neighborhood. And oral cancer doesn’t treat all its zones equally.

Here’s where it most commonly appears:

- Tongue (especially the sides and underside)

- Floor of the mouth (the area under the tongue)

- Buccal mucosa (the inner lining of the cheeks)

- Gums and roof of the mouth

- Lips (particularly the lower lip, often due to sun exposure)

- And the oropharynx, which includes the back of the tongue, tonsils, and soft palate

A subtle ulcer on the side of the tongue that doesn’t heal. A white patch on the cheek that quietly gets thicker. These are how many cases begin — deceptively minor changes that slowly evolve. That’s part of what makes oral cancer dangerous: it can masquerade as a dental issue until it’s not.

1.3 How Common Is It, Really?

Oral cancer isn’t rare. In fact, it’s one of the more frequently diagnosed cancers worldwide, especially in regions with high rates of tobacco use, alcohol consumption, or betel nut chewing.

Globally, over 377,000 new cases of lip and oral cavity cancers are diagnosed annually, according to the World Health Organization. In the U.S. alone, the American Cancer Society estimates over 54,000 new cases in 2024. And the kicker? Over 11,000 deaths are expected from these cancers — most of which could have had a different outcome with earlier detection.

That might prompt another question: “If it’s that common, why don’t we hear more about it?” Unfortunately, oral cancer lacks the media spotlight given to other cancers like breast or prostate. It’s also stigmatized — often associated with smoking, drinking, or sexually transmitted infections (HPV), all of which can discourage open conversation.

But silence isn’t helpful. Knowledge is. Which brings us to an even more critical topic: how — and how fast — this cancer moves.

Progression and Spread of Oral Cancer

So now we arrive at the question that likely brought you here in the first place: How fast does oral cancer spread?

Let’s not dance around it — the answer matters. A lot. Because when you’re dealing with cancer in the mouth or throat, time isn’t just a factor; it’s a determining variable in survival, treatment options, and quality of life. But like most things in medicine, the truth is a little more layered than a simple “fast” or “slow.”

Let’s break it down in real, digestible terms.

What Do We Mean by “Stages”?

First things first — to understand how oral cancer spreads, we need to talk about staging.

Doctors classify oral cancer into stages 0 through IV, based on how big the tumor is (T), whether it’s spread to nearby lymph nodes (N), and whether it’s metastasized to distant organs (M). This is called the TNM system, and here’s how it plays out in general:

- Stage 0 (Carcinoma in situ): Cancerous cells are present, but they haven’t invaded deeper tissues yet. Think of this as a fire smoldering on the surface.

- Stage I and II: Small tumors, typically under 2 cm (Stage I) or up to 4 cm (Stage II), and no lymph node involvement. These are still localized and highly treatable.

- Stage III: The tumor may now be larger than 4 cm or may have reached a nearby lymph node.

- Stage IV: This is when the cancer has either invaded deep structures (like bone or muscle), spread to multiple lymph nodes, or metastasized to distant parts of the body (most often the lungs).

You might ask, “Is the jump from Stage I to Stage III always gradual?” Not necessarily. That’s the tricky — and sometimes terrifying — thing about oral cancer: the transition between stages can be abrupt if the conditions are right (or wrong, depending on your perspective).

So… How Fast Can It Actually Spread?

Here’s the part where we get uncomfortably honest. Oral cancer can spread surprisingly fast. In some aggressive cases, especially with certain high-grade squamous cell carcinomas, a tumor can progress from a small lesion to a node-involved Stage III in as little as 3–6 months.

Yes, months. Not years.

And for patients with contributing risk factors — such as heavy tobacco use, high alcohol consumption, or co-infection with HPV-16, the pace can accelerate further. But even in patients with no clear lifestyle risk factors, some oral cancers behave unpredictably, which makes early detection all the more critical.

One of the most sobering findings from retrospective case reviews is how many patients delay seeking help because the symptoms seem minor: a sore that doesn’t heal, a patch they can’t see, a lump that doesn’t hurt. By the time pain or difficulty speaking or swallowing develops, the tumor has often already spread.

Here’s a question you might be wondering: “Does this mean everyone with a sore in their mouth is at risk of fast-moving cancer?” Not at all. Most mouth sores are benign. But any sore that doesn’t heal within two weeks deserves a professional evaluation. Oral cancer doesn’t wait for a second opinion.

How Does It Spread — and Where Does It Go?

Cancer cells are remarkably opportunistic. Once they break free from their original location, they typically look for two things: nearby lymphatic channels and vascular pathways. The mouth is rich in both.

This makes regional spread — usually to the cervical lymph nodes in the neck — a frequent next step. In fact, for many patients, a firm, painless swelling in the neck is the first outward sign that something is very wrong. And it’s often a sign that the disease has already progressed to Stage III or beyond.

From there, cancer cells can travel to distant organs. The lungs are the most common destination for oral cancer metastasis, followed by the liver and bones. This leap to distant sites marks Stage IV disease and dramatically reduces the chances of long-term survival.

So, let’s revisit the core question again with a more nuanced answer:

How fast does oral cancer spread?

It depends — but in many cases, it moves fast enough that even a few months of delay can shift a patient from a curable early-stage tumor to a life-threatening, advanced disease.

Let’s Flip the Script

All this sounds scary. And yes, some of it is. But let’s also acknowledge the flip side: when caught early, oral cancer is highly treatable and often curable.

The problem isn’t that we don’t have the tools — it’s that people don’t always know when to use them.

This naturally connects with dental detection issues — for instance, whether dental X-rays actually catch cancer or just flag secondary symptoms.

So the real goal here isn’t just to sound the alarm — it’s to change behavior. To help people understand that progression isn’t just about biology. It’s about timing.

Risk Factors Influencing Spread

Let’s be honest: “risk factor” has become such a buzzword that it often floats right past our attention like nutritional labels on fast food. But when it comes to oral cancer — especially how quickly it spreads — risk factors aren’t just background noise. They’re the levers behind the speed, the severity, and sometimes even the survivability.

So, let’s get serious and nuanced about this. Because understanding why some oral cancers progress like wildfire while others creep along more slowly is the key to shifting outcomes. And, in many cases, these are risks we can do something about.

Lifestyle Factors: The Big Three

If oral cancer were a storm, these would be the winds driving it forward.

Tobacco

Here’s the obvious culprit — but that doesn’t make it any less deadly. Tobacco, in all its forms (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, chewing tobacco, snuff, even betel quid), bathes the mucosal lining of your mouth in carcinogens. Not just once, but dozens of times a day for habitual users.

What does this mean in terms of spread? It’s not just about initiation. Long-term tobacco exposure damages the DNA repair mechanisms in oral tissues. So when cancerous changes begin, the body is less equipped to suppress them. More mutations = more aggression = faster spread.

And if you’re wondering, “Is vaping safer in this context?” — the honest answer is we don’t fully know yet. But early studies suggest that heated aerosols still provoke inflammation and DNA damage in oral tissues. Not exactly risk-free.

Alcohol

Alcohol acts like a solvent, making it easier for harmful substances (including those from tobacco) to penetrate the cells in your mouth. In fact, alcohol and tobacco together have a synergistic effect — meaning the combined risk is multiplicative, not additive.

Translation? If you drink and smoke, you’re not doubling your risk. You might be multiplying it by five to ten. And the cancers that arise in this environment are often more aggressive, with faster local invasion and earlier nodal spread.

Sun Exposure (for lip cancers)

If you’ve ever had a blistering sunburn on your lower lip, consider that more than just a cosmetic issue. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a known mutagen — it causes direct DNA damage in skin and mucosal cells. Lip cancer, especially of the lower lip, is disproportionately higher in people who spend a lot of time outdoors without sun protection.

Simple fix? Use a lip balm with SPF. Yes, really.

Biological and Viral Factors

Here’s where the conversation gets more intricate. Because not all risk is chosen — some is inherited, or acquired invisibly.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

HPV — specifically type 16 — has emerged as a game-changer in oral oncology. Unlike traditional oral cancers linked to smoking and drinking, HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers often occur in younger, otherwise healthy adults. Think 40s, non-smokers, no alcohol history.

So what’s different here?

- HPV-positive tumors tend to occur in the back of the tongue and tonsils — less visible and more prone to silent progression.

- They often present later, because the symptoms are subtle and harder to spot.

- And yet — here’s the twist — they tend to respond better to treatment than HPV-negative cancers.

That’s right: biologically aggressive, but therapeutically sensitive. A paradox, and one that researchers are still actively untangling.

Age and Immune Function

Age is a risk factor, yes — most oral cancers occur in people over 50. But chronological age is only part of the story. What really matters is immune competence.

Your immune system constantly surveys for abnormal cells — a process called immune surveillance. When this system is weakened (due to chronic illness, certain medications, or aging), cancer cells are more likely to slip through the cracks and proliferate unchecked.

Genetics and Family History

Some people inherit a higher baseline risk of developing certain cancers, including oral cancers. This can be due to mutations in tumor suppressor genes like p53, or familial patterns of immune dysfunction and poor cellular repair.

That said, a family history doesn’t mean destiny — but it should mean vigilance.

Tumor-Specific Characteristics

Not all tumors are created equal, even if they arise in the same location. Here’s where pathology really starts to matter.

Grade of the Tumor

- Low-grade tumors look more like normal cells and tend to grow slowly.

- High-grade tumors are abnormal-looking, aggressive, and fast-moving.

A biopsy doesn’t just confirm a diagnosis — it tells you what kind of enemy you’re dealing with, and how quickly you need to act.

Location and Depth

Tumors on the surface (like on the lip) are usually noticed early. But those deeper in the oral cavity — the base of the tongue, the tonsillar pillars — often grow quietly until they’ve invaded muscle, bone, or lymphatic channels.

Depth of invasion is also a powerful predictor of metastasis. A tumor that’s just 1-2 mm deep? Probably localized. Beyond 4 mm? The odds of nodal spread increase significantly.

So What Can You Actually Do With This Information?

You might be thinking, “Okay, I get the risks. But what can I control?” The good news: a lot. Most oral cancers are not fate — they’re fallout.

Here’s the actionable takeaway:

- Quit smoking. The earlier, the better — your mucosal cells begin healing within weeks.

- Cut back on alcohol, especially in combination with tobacco.

- Protect your lips from UV exposure.

- Get screened for HPV, and talk to your doctor about the HPV vaccine if you’re eligible.

- Know your mouth. If something feels wrong and doesn’t heal in two weeks, don’t wait.

- And if you’ve already had cancer once? You’re at higher risk for recurrence, so lifelong vigilance is crucial.

Symptoms and Early Detection

Let’s be real — cancer is a master of disguise. Especially oral cancer. It doesn’t barge in like a heart attack; it tiptoes. Quietly. Cunningly. And for too many people, that subtlety is its most dangerous trait.

So here’s the guiding principle of this section: if you wait until oral cancer feels like cancer, you may have already lost the advantage. But if you know what to look for — and act early — you shift the odds dramatically in your favor.

This isn’t about paranoia. It’s about pattern recognition.

Early Warning Signs: What the Body Whispers Before It Shouts

We’re used to associating illness with pain. A throbbing tooth. A sore throat. An inflamed joint. But oral cancer? It often starts painlessly. That’s why early-stage disease can fly under the radar for months — especially when the symptoms overlap with routine nuisances.

Common signs include:

- A sore or ulcer in the mouth that doesn’t heal after two weeks. This one deserves emphasis. A typical canker sore should heal in 7–10 days. Anything beyond that — especially if it’s persistent and painless — demands attention.

- A white or red patch on the gums, tongue, tonsil, or lining of the mouth. Medically, these are called leukoplakia(white) and erythroplakia (red), and they aren’t diagnoses — they’re warnings. Not every patch is cancerous, but a percentage are precancerous or worse.

- A lump or thickening in the cheek or jaw. If something feels “off” when you chew, talk, or run your tongue over the inside of your mouth — pay attention.

- Difficulty swallowing, speaking, or moving the tongue or jaw.

- A persistent sore throat or a feeling that something is “caught” in the throat.

- Numbness or unexplained bleeding.

- A change in voice — sometimes subtle, sometimes gravelly.

- And yes, a lump in the neck, which may be the first sign that the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

Notice how none of these are dramatic Hollywood-style symptoms. No one collapses in pain or coughs blood onto a white napkin in the early stages. That’s why so many people delay. It’s not denial. It’s misinterpretation.

And yet, these small, seemingly forgettable clues — if caught early — can be life-saving.

The Tools of Detection: What Clinicians Actually Look For

You don’t have to become a pathologist to catch oral cancer early. But you do need to understand how professionals screen for it — and why those dental checkups are more than just a quick polish and fluoride rinse.

Dentists are often the first line of defense. They’re trained to spot lesions, asymmetries, tissue changes, or subtle signs of inflammation during a routine oral exam. And here’s something many patients don’t know: every dental checkup should include an oral cancer screening, especially if you’re over 40 or have any of the risk factors we covered earlier.

If something suspicious is found, here’s what usually follows:

- Visual and tactile examination: A good clinician doesn’t just look — they feel. For lumps under the tongue, in the cheeks, and in the lymph nodes of the neck.

- Biopsy: Still the gold standard. If a lesion looks concerning, a small tissue sample is taken and sent to pathology. This tells us whether it’s benign, precancerous, or malignant — and, if cancerous, how aggressive it might be.

- Imaging: Depending on the lesion’s size and location, a CT scan, MRI, or PET scan may be used to assess depth, spread, and lymph node involvement.

- Brush biopsy and adjunctive tools: Some clinics use fluorescence lights or special rinses that make suspicious tissue fluoresce. These aren’t definitive, but they can help highlight areas for closer inspection.

Here’s a question people often ask, even if only to themselves: “Should I be doing self-checks at home?”

Yes — but with nuance. You don’t need a medical degree to keep an eye on your own mouth, especially if you’re high-risk. Once a month, look in the mirror under good lighting. Pull your cheeks out, lift your tongue, look at the roof and floor of your mouth. Anything that doesn’t look symmetrical, doesn’t heal, or feels new? That’s worth flagging.

Why Timing Is Everything

Let’s return to the central theme: speed.

By the time an oral cancer causes visible disfigurement or significant pain, it’s often already advanced. And advanced cancers — even with today’s medical advances — are harder to treat, more likely to recur, and associated with significantly lower survival rates.

Early-stage oral cancers, on the other hand, can often be completely removed with surgery alone. No chemo. No radiation. No feeding tubes or tracheotomies.

That’s the difference a few weeks can make.

Treatment Options

At this point, we’ve covered what oral cancer is, how fast it can spread, who’s most at risk, and how to spot it early. Now comes the inevitable question: What happens next?

The answer depends on a mix of factors — the stage of the cancer, the type of cells involved, your overall health, and even your personal preferences. But one thing is clear: oral cancer treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. It’s more like a series of calibrated decisions, each with its own trade-offs, timelines, and goals.

Let’s take a deeper look at the therapeutic arsenal — what’s available, when it’s used, and how it all fits together.

Surgical Interventions: The First and Often Most Decisive Step

Surgery is the frontline treatment for most localized oral cancers. Why? Because if the tumor is small enough and hasn’t spread, cutting it out cleanly — with clear margins — can be curative.

Margins are key here. When a surgeon removes a tumor, they also take a rim of healthy tissue around it. That buffer zone helps ensure that no microscopic cancer cells are left behind. If cancer is still found at the edge of the removed tissue (a “positive margin”), further treatment is usually needed.

Now, surgery can range from relatively minor — say, removing a small lesion on the tongue — to major, life-altering operations involving part of the jawbone, tongue, or facial muscles. And yes, those more extensive surgeries can be profoundly disruptive. But modern surgical oncology has come a long way.

In many centers, patients now benefit from reconstructive microsurgery — where tissue from other parts of the body (like the forearm or thigh) is used to rebuild what’s been removed. The goal isn’t just survival — it’s also about preserving function: speech, swallowing, facial symmetry. This isn’t vanity. It’s quality of life.

And then there’s the neck. If the cancer has spread or is at high risk of spreading to lymph nodes, a neck dissection — removal of lymph nodes in the neck — is often performed. Sometimes proactively. It may sound drastic, but it can dramatically reduce recurrence.

Radiation and Chemotherapy: Powerful, Strategic, and Sometimes Punishing

Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams to destroy cancer cells. It’s often used:

- After surgery, to kill any residual cells (this is called adjuvant therapy)

- Instead of surgery, in cases where the tumor can’t be easily removed or the patient isn’t a surgical candidate

- Alongside chemotherapy, in more advanced cases

And while modern techniques like intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) have made it possible to target tumors with far greater precision — sparing healthy tissue — radiation in the head and neck is still a tough road. We’re talking dry mouth, difficulty swallowing, loss of taste, mucositis (painful mouth sores), and increased risk of long-term dental complications.

Chemotherapy, on the other hand, is systemic. It affects the whole body. In oral cancer, it’s rarely used on its own — it’s more often given:

- In combination with radiation (known as chemoradiation) for locally advanced disease

- Before surgery (called neoadjuvant therapy) to shrink a large tumor

- After other treatments, if there’s concern about spread or recurrence

The most common drugs? Cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil, both workhorses in head and neck cancer care. These can cause fatigue, nausea, lowered immunity, and neuropathy, but they also increase survival odds when used appropriately.

And yes, patients often ask: Is it worth it? That depends. But for many, especially those with stage III or IV cancers, these treatments can add years — or save lives altogether.

Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapy: The Frontier of Precision Oncology

This is where things get exciting — and complicated.

Targeted therapies home in on specific molecules that cancer cells use to grow and divide. For oral cancer, one such target is EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor), a protein often overexpressed in squamous cell carcinomas.

The most widely used drug in this category is cetuximab, which binds to EGFR and helps slow cancer growth. It’s generally less toxic than traditional chemo, though not without side effects (notably skin rashes and infusion reactions).

Then there’s immunotherapy, which leverages the body’s own immune system to fight cancer. Drugs like nivolumaband pembrolizumab — both immune checkpoint inhibitors — are now approved for recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancers that haven’t responded to other treatments.

These therapies don’t work for everyone. But when they do, they can produce long-lasting remissions, even in patients with advanced disease. And they signal a shift in philosophy: from bombing cancer cells indiscriminately to retraining the body to recognize and destroy them.

Concerned about specific dental work? There’s a useful breakdown in Can Dental Crowns Cause Cancer.

We’re not talking science fiction. We’re talking standard-of-care — for the right patients, at the right stage.

Where Treatment Decisions Happen

Here’s a behind-the-scenes truth: oral cancer care doesn’t happen in silos. Treatment planning is multidisciplinary, meaning surgeons, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, pathologists, and speech-language therapists often huddle together to design a personalized approach.

This is known as tumor board review, and it exists for a reason: oral cancer sits at the crossroads of survival and function. Decisions aren’t just about life and death — they’re about how you live, after.

Prognosis and Survival Rates

By the time someone reaches this point in an article about oral cancer — having digested what it is, how it behaves, what causes it, and how it’s treated — they’re not just curious. They’re invested. Maybe they’re a patient, maybe a loved one, or maybe someone trying to make sense of a diagnosis that came too close for comfort. Either way, the next logical — and most emotionally charged — question is simple: What are the chances?

And while the science of cancer prognosis is a field of nuance, statistics, and caveats, it still offers a clear message: early detection saves lives. But even in later stages, meaningful survival is possible. Let’s unravel the numbers — and more importantly, what they mean in real life.

Reading the Survival Curve: What the Numbers Actually Say

In cancer care, prognosis is usually discussed in terms of the 5-year survival rate — the percentage of people alive five years after diagnosis. It’s a rough benchmark, not a finish line, and it doesn’t mean the cancer will return after five years or that someone is “safe” at that point. But it helps compare outcomes across stages.

Let’s look at oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers specifically:

- Stage I (small, localized tumor): ~85% 5-year survival

- Stage II (larger tumor, still no nodes): ~70%

- Stage III (local spread to lymph nodes): ~55–65%

- Stage IV (advanced or metastatic): ~35–45%, sometimes lower depending on extent

These are U.S. averages based on SEER data. They vary by country, access to care, and sub-type of oral cancer. For example, HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers — despite often being diagnosed later — tend to respond better to treatment and carry a more favorable prognosis.

But here’s the part that doesn’t always make the headlines: survival rates have been slowly improving, thanks to earlier detection, better imaging, more nuanced surgical approaches, and the rise of targeted therapies and immunotherapy. A diagnosis that once carried grim inevitability now carries complexity — and, often, hope.

Why Two Patients With the Same Stage Might Have Different Outcomes

Cancer staging is a powerful tool, but it’s only one part of the equation. Think of it as a weather forecast. Two people can be caught in the same storm — one might walk away dry, the other drenched. Why? Because of where they stood, what they brought with them, and how quickly

Here are a few of the biggest modifiers that shape prognosis:

Biological Behavior of the Tumor

Some tumors are inherently more aggressive — based on their cell grade, growth patterns, or genetic mutations. A low-grade squamous cell carcinoma might sit quietly for months, while a high-grade variant could spread rapidly despite early-stage classification.

Depth of Invasion

Tumor size matters — but depth matters more. A thin, wide lesion may be less threatening than a narrow but deep one that’s reached into muscle or bone. Deeper tumors are more likely to spread to lymphatics and recur locally.

HPV Status

We’ve touched on this already, but it’s worth emphasizing: HPV-positive tumors, particularly in the oropharynx, tend to behave differently. They’re often more responsive to treatment and carry a better long-term prognosis, even when detected at an advanced stage.

Patient Age and Health

Younger, otherwise healthy patients tolerate surgery, radiation, and chemo better. They bounce back faster, maintain stronger immune function, and have fewer treatment-related complications. Older patients — or those with comorbidities like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or immunosuppression — may face steeper risks, even with the same disease stage.

Access to and Continuity of Care

This is the elephant in the room: healthcare disparities. Two patients with identical tumors can have radically different outcomes based on when they were diagnosed, who treated them, and how well follow-up care was coordinated.

Geography, insurance, race, and socioeconomic status still influence outcomes. That’s not a medical issue — it’s a systems issue. But it directly impacts survival.

Recurrence: The Long Shadow

Beating oral cancer doesn’t always mean the end of the journey. Many patients live with the question: Will it come back?For some, this anxiety fades over time. For others, especially those with high-risk features, recurrence is a real concern.

Recurrent oral cancers may appear:

- At the original site (local recurrence)

- In regional lymph nodes

- At distant sites like the lungs, bones, or liver

Most recurrences happen within the first two years after treatment. That’s why follow-up care — including regular imaging, clinical exams, and sometimes tumor marker testing — is structured so intensively in the early months and years.

And if the cancer does return? The treatment strategy changes. Sometimes surgery is possible again; sometimes not. Immunotherapy may come into play. Clinical trials can become lifelines. The conversation becomes about management, not just cure — a distinction that many patients learn to live with, and live well.

Prevention and Risk Reduction

Let’s take a breath here — because this is the part of the conversation where control begins to shift. Up to this point, much of the discussion around oral cancer may have felt diagnostic, even reactive: Here’s what happens when cancer appears. Here’s how it behaves. Here’s how we fight it.

But what if we flipped the timeline?

What if we asked not, “How do we treat oral cancer?” but “How do we prevent it from ever taking hold in the first place?”

Because make no mistake: oral cancer is one of the most preventable major cancers worldwide. And while not all cases are avoidable — we don’t choose our genetics, after all — the vast majority of risk is modifiable. That’s the real power here.

7.1 Lifestyle Modifications That Actually Move the Needle

You’ve heard it before, but let’s say it plainly: tobacco is the single most preventable cause of oral cancer. Whether smoked, chewed, vaped, or packed in betel nut — it acts like fertilizer for cellular mutation. There’s no safe level, and no form that avoids risk.

Quitting isn’t just damage control — it’s reversal. Within five years of stopping tobacco use, your risk of developing oral cancer can be cut in half. After a decade, it may approach that of someone who never smoked. The body doesn’t forget everything, but it does forgive more than we expect.

Alcohol is next in line. Alone, it increases risk modestly. Combined with tobacco? The risk multiplies — not linearly, but exponentially. The science behind this synergy is biochemical: alcohol dries and irritates the mucosa, making it more permeable to carcinogens. Think of it as softening the soil so toxins can sink in deeper.

Reducing alcohol doesn’t have to mean abstinence. But moderation matters. And for those with a history of oral lesions, heavy drinking becomes more than a lifestyle concern — it’s a clinical red flag.

And then there’s sun exposure, often forgotten in the oral cancer conversation. But the lips — especially the lower lip — are frequent sites of squamous cell carcinoma, particularly in fair-skinned individuals who work or spend time outdoors. The fix is elegantly simple: SPF lip balm. Protective hats. Awareness. It’s not high-tech, but it’s high-yield.

The HPV Factor: Vaccination as Cancer Prevention

When it comes to public health wins, few are as elegant or impactful as the HPV vaccine. Originally developed to prevent cervical cancer, it’s now known to reduce the incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers — particularly in men, who are disproportionately affected in that anatomical region.

HPV-positive oral cancers don’t behave exactly like those driven by smoking or alcohol. They tend to strike younger people. They often arise deeper in the throat, where they’re harder to see. But they are still cancer, and they are increasingly common.

The vaccine is most effective when given before exposure to the virus, ideally in adolescence. But it’s approved for adults up to age 45 in many countries. And it’s not just a shot against a virus — it’s a shot against a future diagnosis, a future round of chemo, a future time bomb.

Regular Screenings: The Unflashy Hero of Prevention

It’s tempting to think prevention only means behavior change. But surveillance is prevention, too — especially in those with a history of risk factors, precancerous lesions, or previous cancers.

For most people, this means:

- Biannual dental checkups, with an oral cancer screening included. Not all dentists emphasize this — but they should, and you can ask.

- Self-awareness: Know your mouth. Look at it. Feel around. A sore, a patch, a lump — if it persists beyond two weeks, act.

- Follow-up for suspicious lesions: If a biopsy shows dysplasia or atypia, close monitoring is critical. These aren’t cancers, but they’re signals. Some go on to transform. Others regress. But they are, without question, worth watching.

- Post-treatment surveillance: For those who’ve had oral cancer before, prevention means guarding against recurrence. This typically involves regular physical exams, imaging when needed, and close communication between oncology and dental teams.

The real challenge here isn’t just getting screened — it’s staying engaged. Preventive care doesn’t deliver the dopamine hit of a cure or a dramatic diagnosis. But over time, it delivers something even more valuable: stability. Longevity. Peace of mind.

Emerging Research and Future Directions

If the rest of this article has felt like looking squarely at what we already know, this part is about what we’re learning next. Because oral cancer, like most cancers, isn’t a static foe. It evolves — and so does the science we use to fight it.

Yes, we’ve made real strides. Modern surgeries are more precise. Radiation is smarter. Chemotherapies are better tolerated. But what’s coming on the horizon could shift the entire landscape — not just how we treat oral cancer, but how we detect it, how we predict it, and maybe even how we prevent it altogether.

Let’s talk about what’s in the pipeline — not hypotheticals, but real innovations already shaping the next decade of care.

8.1 Revolutionizing Detection: From Mirrors to Molecules

Traditionally, detecting oral cancer has relied on what you can see and feel: a lesion, a lump, a persistent sore. But by the time these signs appear, cancer may have been brewing for weeks or months.

Researchers are now pushing detection into the molecular realm, where warning signs can be caught long before anything is visible.

One major breakthrough? Salivary diagnostics. Saliva, it turns out, is a treasure trove of biomarkers — DNA fragments, RNA transcripts, proteins — all circulating quietly and offering clues to what’s happening deeper in the tissue.

Imagine a test where a simple spit sample can flag early-stage oral cancer. No needles. No biopsies. Just a vial, an assay, and a yes-or-no readout. These aren’t science fiction; clinical trials are already underway to validate several saliva-based panels for squamous cell carcinoma.

And that’s not all. AI is now being trained to analyze oral images — from intraoral photos to 3D scans — and flag suspicious lesions with astonishing accuracy. In the future, a dentist might be able to upload a picture and receive an instant second opinion from an algorithm trained on hundreds of thousands of cases.

We’re not there yet. But we’re close.

The New Frontier of Treatment: Precision, Personalization, and Immune Engineering

If there’s one word that defines the future of oral cancer treatment, it’s personalization. Gone are the days when one-size-fits-all chemotherapy was the endgame. Today’s approach is less about blasting all dividing cells, and more about understanding what makes each tumor unique — genetically, behaviorally, immunologically — and then attacking that.

Take genomic profiling. Tumors now can be sequenced down to the letter, identifying mutations that drive growth or resist treatment. Some of these can be directly targeted — with existing drugs or experimental agents designed to block a specific pathway.

For instance, tumors with certain EGFR mutations may respond to monoclonal antibodies like cetuximab. Others with PIK3CA or TP53 aberrations might be enrolled in trials testing drugs tailored to those mutations. We’re talking about bespoke therapy plans, built not just around stage and size, but around the actual genetic blueprint of the tumor.

Meanwhile, immunotherapy continues to expand. The checkpoint inhibitors we mentioned earlier — drugs that “wake up” the immune system to attack tumors — are being tested in new combinations and earlier disease stages. Trials are exploring whether these agents can be used before surgery, to shrink tumors and possibly spare more of the face and mouth.

Even cancer vaccines are in development — not just to prevent HPV, but to train the immune system to attack existing oral cancer cells. Imagine a world where your immune system could be trained to recognize your tumor like a fingerprint — and go after it relentlessly.

And then there’s the broader category of cell-based therapies — like CAR-T cells — which are still in early stages for solid tumors but hold long-term promise. If adapted successfully, these could one day be programmed to hunt and destroy oral cancer cells with surgical precision, minus the scalpel.

8.3 Public Health and Policy: Awareness Isn’t Optional Anymore

Innovation doesn’t happen only in labs. Some of the biggest breakthroughs in oral cancer outcomes may come from policy, public health education, and equity in care.

We now know that where you live and what you earn can dramatically affect whether your oral cancer is caught early or late. That’s not a failure of biology — it’s a failure of access. And researchers, nonprofits, and government bodies are finally taking it seriously.

New awareness campaigns are aiming to train dental professionals more thoroughly in early detection, to educate patients about HPV and vaccination, and to distribute screening resources in underserved communities, including mobile diagnostic units and subsidized dental care.

Imagine a community van that can roll into a rural town and provide high-resolution oral exams, salivary diagnostics, and AI-enhanced screenings — all in a single afternoon. Not years away. Already happening in pilot programs.

And for those comparing progression speeds, Early Skin Metastases in Breast Cancer offers a contrasting but informative spread profile.

And don’t underestimate the influence of policy. Regulations that restrict tobacco sales, limit flavored vaping products, and require sunscreen labeling for lip balms may sound small — but on a population level, they can alter the trajectory of disease.

All of this points to one powerful reality: we are no longer limited to reacting to oral cancer. We’re beginning to predict it, intercept it, and in many cases, outsmart it.

The more we invest in research, access, and education, the more we shift from a model of crisis management to one of proactive control.

Frequently Asked Questions

Even after a deep dive like this, certain questions tend to echo louder than others — the kind that cling to your thoughts late at night, or bubble up when you’re driving in silence. These aren’t abstract queries; they’re the kind you ask when you’re worried about yourself or someone you love. They deserve straight, well-reasoned answers, grounded in both science and clinical perspective.

Let’s walk through them — not as a checklist, but as a final layer of clarity.

1. How fast can oral cancer actually spread?

This is one of those questions people often ask after the fact — once a diagnosis is already on the table. And the truth is, there’s no single pace. Oral cancer can unfold slowly, smoldering in precancerous stages for months or even years. But it can also pivot fast, especially once it becomes invasive. In certain high-grade squamous cell carcinomas, local invasion and lymphatic spread can happen within a matter of months — not years. That’s why delays in diagnosis matter so much. The earlier it’s found, the more manageable it is.

2. What are the earliest signs I should never ignore?

Most people think “pain” equals “problem,” but in oral cancer, the earliest red flags are usually painless. That’s what makes them so dangerous. A sore that doesn’t heal after two weeks. A white or red patch inside your cheek or on your tongue. A small lump that wasn’t there last month. Subtle changes in speech. Swallowing that suddenly feels effortful. These signs don’t need to shout. If they linger, they’re already speaking loudly enough.

3. If I’ve never smoked or drank, am I still at risk?

Absolutely. Tobacco and alcohol are powerful drivers of oral cancer, but not exclusive ones. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer is rising, especially among younger adults with no history of smoking or drinking. And then there are other contributors — immune status, genetics, poor oral hygiene, even chronic irritation. Risk doesn’t require guilt. It requires awareness.

4. Is oral cancer preventable?

In many cases, yes — or at least, significantly reducible. Quitting tobacco, moderating alcohol, getting vaccinated against HPV, protecting your lips from UV, and seeing a dentist regularly — these aren’t just “healthy habits.” They’re risk-lowering interventions. You can’t prevent all cases, but you can drastically cut your odds.

5. How is oral cancer diagnosed?

Usually, it begins with a visual and tactile exam — often by a dentist, sometimes by a physician. If something looks or feels suspicious, a biopsy follows. That’s the definitive step: a small piece of tissue is removed and analyzed under a microscope to confirm whether it’s benign, precancerous, or malignant. If cancer is confirmed, imaging studies (CT, MRI, PET) help determine its stage and whether it has spread.

6. What are the treatment options, and how are they chosen?

Treatment is based on stage, location, cell type, and overall health. Early-stage tumors often require surgery alone. Advanced stages usually need a combination: surgery, radiation, and sometimes chemotherapy or targeted drugs. HPV-positive cases may follow a slightly different path. Increasingly, treatment is planned by a multidisciplinary team — not just a surgeon or oncologist in isolation, but a panel of experts collaborating on what gives you the best shot at both survival and recovery.

7. What are the survival rates?

They vary widely by stage. Caught early (Stage I), oral cancer has a five-year survival rate of around 85%. Stage III drops that to around 50–65%. Stage IV? Closer to 35–45%, depending on the extent of spread and the patient’s baseline health. But even here, numbers don’t capture nuance. Some late-stage patients survive and thrive. Some early-stage patients recur. Survival statistics are starting points — not forecasts.

8. Can it come back after treatment?

Yes, recurrence is a real risk — especially in the first two years post-treatment. That’s why surveillance is critical. Recurrence can be local (same site), regional (lymph nodes), or distant (lungs, bones). The goal after initial treatment isn’t just to celebrate remission, but to stay vigilant.

9. What role does HPV vaccination play?

A major one. The HPV vaccine doesn’t just reduce cervical cancer — it’s also protective against HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers, which are among the fastest-growing cancer types in younger adults. Vaccinating adolescents — and eligible adults up to age 45 — is a powerful tool in the prevention arsenal. It’s cancer prevention, delivered through a syringe.

10. If I’m worried, what’s the very first step?

Trust your gut — and act early. Schedule a dental or medical exam. Describe the symptoms. Ask specifically about an oral cancer screening. Don’t downplay, and don’t delay. Two weeks is the rule: if something hasn’t healed or resolved in that time, it needs a closer look. You don’t have to know what’s wrong. You just have to ask someone who does.

Closing Thoughts

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve done something that far too few people do: you’ve taken oral cancer seriously before it becomes personal. Or perhaps it already has — perhaps you’re reading this with a diagnosis in hand, or a loved one on your mind. Either way, what matters now is what you carry forward.

Because here’s the truth: oral cancer is a paradox. It’s one of the most visible cancers, yet it often goes unnoticed. It’s one of the most preventable, yet thousands still fall victim each year. And while it can be devastating when caught late, it is exceptionally treatable when found early.

What determines the difference between those outcomes isn’t luck. It’s awareness. It’s access. It’s timing. It’s someone deciding not to dismiss that sore spot, that persistent patch, that nagging hoarseness. It’s a dentist who doesn’t rush through the screening. It’s a patient who speaks up, even if nothing “hurts.” It’s a clinician who biopsies first and assumes nothing.

Throughout this article, we’ve unpacked the speed and behavior of oral cancer, explored the science of diagnosis and staging, walked through the rigors of treatment and recovery, and looked to the future — a future that promises earlier detection, more precise therapies, and broader access to care.

But in the end, the future of oral cancer isn’t just something to be observed from a distance. It’s something you help shape.

You shape it every time you say no to tobacco. Every time you ask for an oral cancer screening at your dental visit. Every time you encourage someone to get vaccinated against HPV. Every time you notice something unusual in your mouth and refuse to ignore it.

And if you’re already in the thick of it — already navigating treatment, grappling with scars, rebuilding your speech or smile — then you’re already proof of something more important than any statistic: that surviving oral cancer isn’t just about living. It’s about reclaiming identity, voice, and future.

This article was never just meant to inform. It was meant to be your final stop — a place where answers find clarity, where fear meets strategy, and where knowledge becomes action.

Take it with you. Share it with someone who needs it. And most of all, remember this:

Your mouth is part of your body — not separate from it, not exempt. Respect it, observe it, listen to it.

Because the sooner we all do that, the quieter oral cancer becomes.