How Breast Cancer Spreads to the Liver and Skin: What to Know

How Breast Cancer Spreads to the Liver and Skin: What to Know

- Foreword

- Part 1: What Is Breast Cancer Metastasis?

- Part 2: Why the Liver and Skin Are Common Targets

- Part 3: Signs and Symptoms of Breast Cancer Spread to the Liver

- Part 4: How Breast Cancer in the Liver Is Diagnosed

- Part 5: Signs and Symptoms of Breast Cancer Spread to the Skin

- Part 6: How Breast Cancer in the Skin Is Diagnosed

- Part 7: How Breast Cancer Metastasis to Liver and Skin Is Treated

- Part 8: Prognosis After Breast Cancer Spreads to the Liver and Skin

- Part 9: FAQs About Breast Cancer Metastasis to Liver and Skin

- Closing the FAQs

- Part 10: Final Thoughts

Foreword

Hearing that breast cancer has spread — to the liver, to the skin, or anywhere else — is the kind of moment that changes everything. It’s not just another step in a medical journey; it’s a turning point, one that reshapes hopes, fears, and plans all at once.

If you’re reading this, you may be facing that kind of moment right now. Maybe you’ve just learned about new spots found on a scan. Maybe you’ve noticed strange changes on the skin near a surgery scar. Maybe you’re sitting with someone you love, trying to make sense of what a doctor said in rushed, clinical words that didn’t seem to match the gravity of the news.

This article isn’t here to soften the truth — metastasis is serious. But it’s also not here to strip away hope. Many patients live meaningful, rich, joyful lives after a diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer. Treatments are better now than they were even a few years ago. Survival times are improving. And understanding what’s happening — clearly, honestly, without false promises but also without unnecessary despair — can give you back some sense of footing.

We’ll walk carefully through how breast cancer spreads, why the liver and skin are vulnerable, what symptoms to watch for, how doctors confirm the diagnosis, and what treatment options exist today. We’ll also talk about what living with metastatic breast cancer can really look like — beyond statistics and medical jargon.

Let’s start with the basics: what exactly is breast cancer metastasis, and how does it happen?

Part 1: What Is Breast Cancer Metastasis?

When doctors talk about breast cancer “spreading,” they’re talking about metastasis. Metastasis means that cancer cells have broken away from the original tumor in the breast, traveled through the body — usually through blood vessels or lymphatic channels — and settled in other organs or tissues where they start to grow again.

It’s not a matter of the original tumor physically growing outward into distant places. Instead, it’s a microscopic journey. A few rogue cells slip away, survive the harsh environment of the bloodstream, evade the immune system, and find a new home where they can take root. Once there, they behave much like the original cancer, but now in a place where they don’t belong.

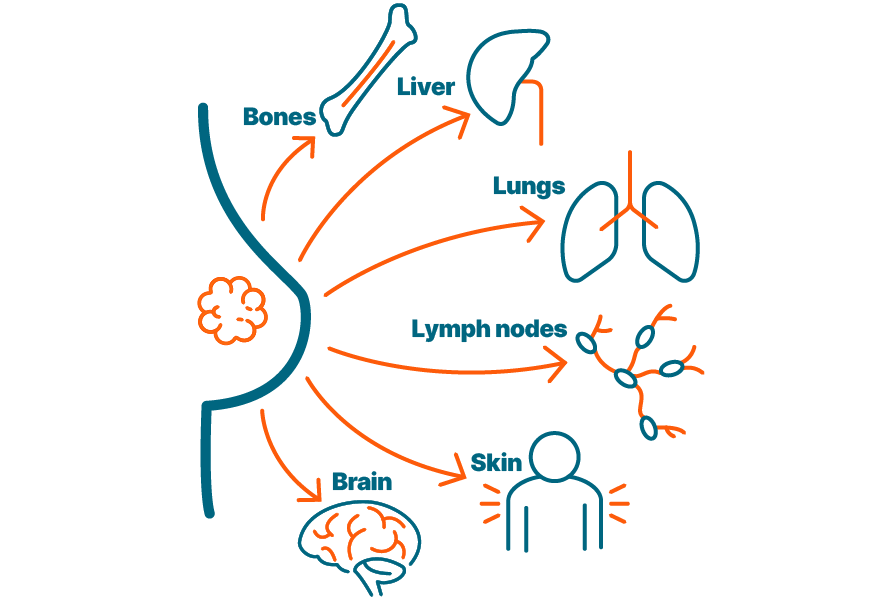

Breast cancer most commonly metastasizes to certain key areas: the bones, the lungs, the liver, the brain, and the skin. Each site brings its own challenges, symptoms, and treatment considerations.

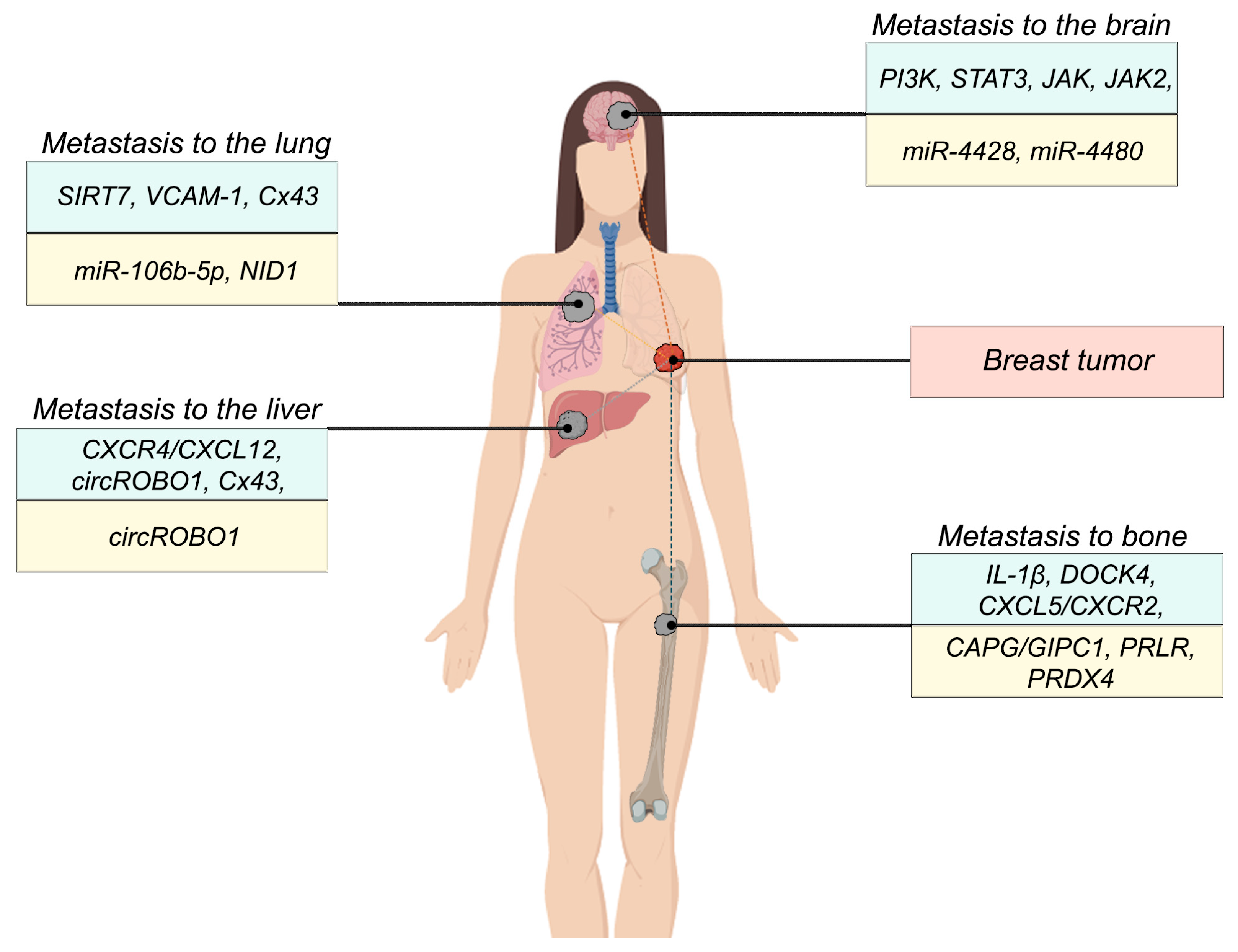

You might wonder why some breast cancers spread quickly, while others stay localized for years. The answer lies partly in the biology of the tumor itself. Aggressive tumors, like triple-negative or HER2-positive cancers, tend to spread earlier and more unpredictably. Hormone receptor-positive cancers often grow slower and may stay confined longer before eventually spreading, sometimes even many years after initial diagnosis.

Not every case of breast cancer will metastasize. Many early-stage breast cancers are caught and treated before any spread occurs. But when metastasis does happen, it marks a shift: breast cancer is no longer considered curable in the traditional sense. Instead, the goal of treatment becomes controlling the disease, managing symptoms, prolonging survival, and maintaining quality of life.

Understanding metastasis isn’t about giving up hope. It’s about facing the reality of what the cancer is doing — and using that understanding to fight smarter, not harder.

Now that we’ve laid out the basics, let’s take a closer look at why the liver and the skin, specifically, are such common targets for breast cancer cells on the move.

Part 2: Why the Liver and Skin Are Common Targets

Breast cancer doesn’t spread randomly. Cancer cells tend to follow patterns, traveling through blood vessels and lymphatic channels toward specific organs where they can survive and grow. The liver and the skin are two of those favored destinations, and understanding why helps explain a lot about how metastatic breast cancer behaves.

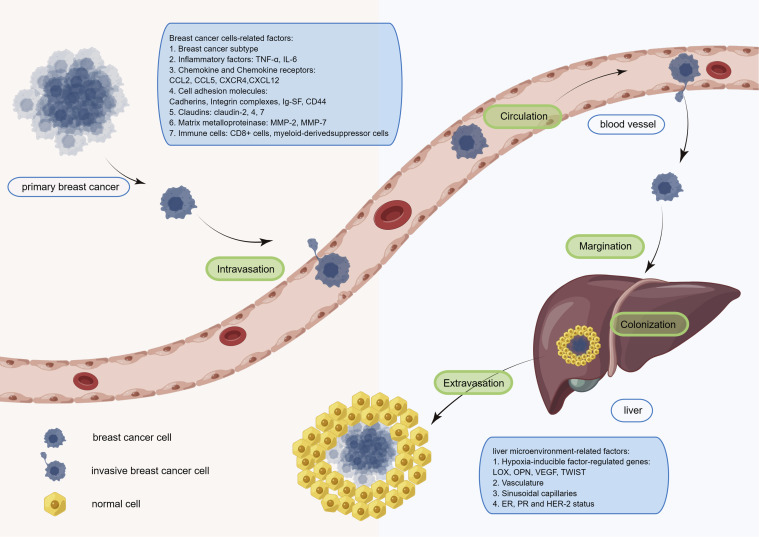

The liver is especially vulnerable because of its role as the body’s natural filter. Every minute, about 1.5 liters of blood pass through the liver, carrying nutrients, toxins, and — sometimes — wandering cancer cells. The liver’s dense network of tiny blood vessels (called sinusoids) acts like a sieve, trapping cells that might otherwise circulate freely. While this filtering system is vital for health, it also gives cancer cells the perfect opportunity to lodge themselves, survive, and start forming new tumors.

Skin metastases happen differently. The breast, chest wall, and nearby skin areas are rich with lymphatic vessels — tiny channels that drain fluid and immune cells through the body. When breast cancer cells invade these lymphatic pathways, they can travel into the skin, setting up colonies either near the original tumor site (local recurrence) or farther away. Sometimes, skin metastases are the first outward sign that cancer has recurred or spread.

Certain types of breast cancer seem more prone to targeting the liver or skin:

- Invasive lobular carcinoma, which tends to spread to unusual places like the gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, or skin more often than ductal carcinoma.

- Inflammatory breast cancer, which aggressively invades lymphatic channels and can rapidly cause skin involvement.

- HER2-positive and triple-negative cancers, which have a higher overall risk of distant metastases, including to the liver.

It’s also important to know that the liver and skin aren’t exclusive targets. Breast cancer cells can — and often do — spread to multiple sites at once. A woman may have bone and liver metastases simultaneously, or skin lesions and lung nodules appearing within the same window of time.

Recognizing how and why these sites are chosen isn’t just academic. It shapes how doctors monitor for recurrence, how they interpret vague symptoms, and how they plan scans and treatments once metastasis is suspected.

Next, we’ll focus more closely on the signs that suggest breast cancer might have spread to the liver — signs that can be easy to overlook until the disease is already well underway.

Part 3: Signs and Symptoms of Breast Cancer Spread to the Liver

Breast cancer spreading to the liver is often an insidious process, where symptoms can remain mild or absent during the early stages. In fact, some patients don’t experience noticeable symptoms at all until the disease has progressed significantly. This can make liver metastasis particularly difficult to detect early without routine screening.

At first, the signs can be so subtle that they might be overlooked or attributed to other, more common causes. One of the most common early symptoms is fatigue. It’s not just ordinary tiredness; it’s a deep, persistent exhaustion that doesn’t seem to improve with rest. For many patients, this can be an early warning sign that something is wrong, especially when combined with other less noticeable symptoms.

Alongside fatigue, some individuals may feel mild discomfort or pressure in the upper abdomen, particularly on the right side. This can be due to the liver starting to swell as cancer cells begin to settle there and grow. It may feel like bloating or fullness, and it often gets worse as the liver becomes more congested. This discomfort can be mistaken for something like indigestion, making it easy for owners or doctors to miss the connection to liver involvement.

As the cancer progresses, the symptoms typically become more pronounced. One of the clearer signs of liver metastasis is pain in the right upper abdomen. This pain might start as a dull ache, but it can become sharp and intense as the liver becomes more affected. The pain can sometimes radiate into the back or under the shoulder blade, which can also be confusing, as it’s not always immediately obvious that it’s coming from the liver.

When liver metastasis becomes more advanced, the body’s ability to process bilirubin — a substance produced during the breakdown of red blood cells — can be impaired, leading to jaundice. Jaundice is noticeable by the yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes, a clear sign that the liver is struggling to do its job.

Swelling in the abdomen is another late-stage symptom of liver involvement, often caused by fluid buildup in the peritoneal cavity (a condition known as ascites). This can cause the abdomen to feel full, tight, and uncomfortable, and is sometimes noticeable even without a medical examination.

Additionally, itching without an obvious rash can develop as a result of bile salts accumulating in the skin due to the liver’s impaired ability to process them. This symptom, though not specific, can be a sign of liver dysfunction.

In some cases, these symptoms may seem unrelated at first or mild enough to be brushed off. However, for anyone with a history of breast cancer, they should never be ignored. Elevated liver enzymes detected through blood tests — such as AST, ALT, and bilirubin — can offer an early clue. These tests are often part of regular cancer monitoring and can provide important information long before more serious symptoms show up.

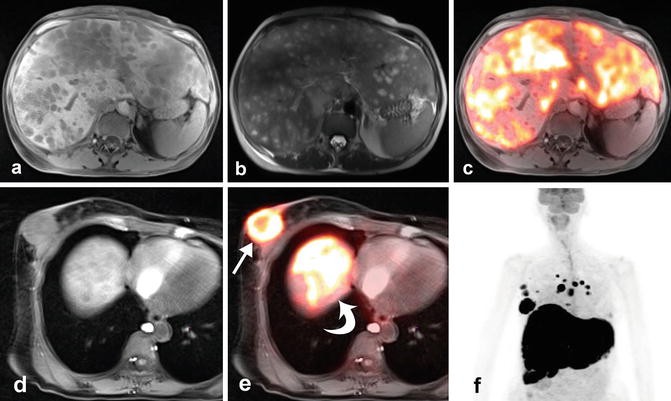

However, blood tests alone aren’t enough to confirm liver metastasis. The real confirmation comes through imaging studies like ultrasound, CT scans, or MRIs. These tools give doctors the detailed images needed to check for tumors, fluid accumulation, and other signs of liver involvement. Without these imaging tools, it’s impossible to know for sure where the cancer has spread and how it’s affecting the liver.

Now that we understand the symptoms, let’s talk about how doctors diagnose breast cancer that has spread to the liver — and why early and accurate diagnosis matters so much.

Part 4: How Breast Cancer in the Liver Is Diagnosed

When breast cancer spreads to the liver, the diagnosis isn’t always straightforward. Symptoms can be vague, and the liver’s vital role in filtering the blood means changes can happen slowly. Because of this, early detection is often made through regular screening or when blood tests start to show unusual results. Let’s look at the diagnostic steps a veterinarian or doctor will typically take when metastasis to the liver is suspected.

First, blood tests are often the first line of investigation. Liver function tests are designed to measure how well the liver is working and to detect early signs of damage. These tests measure levels of certain enzymes (like ALT, AST, and ALP) and proteins that the liver normally produces. When these values are elevated, it can be a sign that the liver is struggling, possibly due to metastasis or other conditions affecting its function. Bilirubin levels may also rise, contributing to jaundice — a common sign of liver involvement. While elevated liver enzymes alone can’t confirm metastasis, they are important clues and typically prompt further investigation.

If blood work indicates liver involvement, doctors will turn to imaging to get a clearer picture. Ultrasound is a common first step in diagnosing liver metastasis. This non-invasive procedure uses sound waves to create images of the liver, helping doctors see the size of the organ, the presence of any masses, and any fluid buildup (such as ascites). An ultrasound is quick and effective, but it doesn’t provide a complete look at deeper tissues, so doctors may follow up with additional imaging techniques.

CT scans and MRI scans offer much more detailed images of the liver and surrounding organs. They’re particularly useful when doctors need to evaluate the full extent of the metastasis — how many tumors are present, how big they are, and whether they’re affecting surrounding structures. These imaging techniques also help identify other potential metastases in areas like the lungs or lymph nodes, which are important for staging the cancer.

Once doctors have a clear image of the liver, they may suggest a biopsy to confirm the presence of cancer cells. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is often the first option. This involves inserting a small needle into the suspected tumor to collect a sample of cells. The sample is then examined under a microscope to confirm whether the cells are cancerous and, if so, what type of cancer they are. In some cases, doctors may opt for a core biopsy if they need a larger sample to make a more accurate diagnosis.

While biopsies are helpful, they’re not always necessary. In many cases, if imaging and blood tests strongly suggest liver metastasis from breast cancer, doctors may proceed with treatment based on the clinical picture. However, confirmation through biopsy ensures that the treatment plan is as accurate as possible, especially when determining whether the cancer has spread beyond the liver.

Once all diagnostic steps are completed, the full extent of the liver involvement is understood, and doctors can move forward with treatment planning. This is a crucial point in the journey, where each decision — from chemotherapy to radiation therapy — is guided by the specifics of the metastasis.

Now that we’ve covered how liver metastasis is diagnosed, let’s shift to how doctors address skin metastasis — another common site where breast cancer can spread.

Part 5: Signs and Symptoms of Breast Cancer Spread to the Skin

When breast cancer spreads to the skin, the symptoms can be strikingly visible. Unlike internal metastases to organs like the liver, skin metastases are often seen and felt right away, which can make them more alarming to owners and caregivers. However, even with visible signs, it can sometimes be challenging to distinguish between a new metastatic lesion and a local recurrence, so clear awareness of the symptoms is key.

Skin metastases from breast cancer can appear in several ways, depending on how the cancer cells travel and grow. One of the most common early signs is the development of skin nodules or lumps. These can appear anywhere on the body but are most often found near the original site of the breast tumor, often in the chest or underarm area. These lumps might feel firm or rubbery to the touch, and they can range in size from small and hard to large and soft, depending on the depth and spread of the tumor.

The appearance of redness, swelling, or irritation around the lumps is another frequent sign of skin metastasis. The skin may look inflamed or irritated, which can be mistaken for an infection, but in this case, the redness usually doesn’t resolve with antibiotics. It can persist and even worsen over time as the tumor continues to grow.

As skin metastases progress, they may undergo ulceration — where the surface of the skin breaks down, forming open sores that may ooze blood or pus. This ulceration often happens when the tumor grows large enough to push through the skin, causing the overlying tissue to break down and become necrotic (dead). The wound can become painful and difficult to treat, especially if the underlying cancer continues to spread.

Another characteristic of skin metastasis is peau d’orange — a condition where the skin takes on a texture resembling the surface of an orange. This is due to the underlying tumor blocking lymphatic drainage, causing fluid buildup in the skin. This symptom is often seen in inflammatory breast cancer but can also occur in other types of metastatic disease when the skin’s lymphatic system becomes obstructed.

While these symptoms are most often seen near the original tumor site, skin metastases can appear anywhere on the body. It’s not uncommon for cancer cells to travel through the lymphatic system, pop up at distant sites, and present as unexpected skin lesions in places far removed from the initial tumor.

The early recognition of these symptoms is important for a few reasons. Skin metastases are visible and accessible, making them easier to biopsy and diagnose than metastases in deeper organs. Early biopsy can confirm whether the lesions are cancerous, helping doctors tailor the treatment plan. However, because these lesions indicate that cancer has spread beyond the original site, they typically signal the need for more aggressive systemic therapy, like chemotherapy or immunotherapy, to manage the disease.

Next, we’ll dive into how doctors diagnose skin metastasis from breast cancer, explaining the steps they take to confirm the presence of cancer and determine the best treatment approach.

Part 6: How Breast Cancer in the Skin Is Diagnosed

Diagnosing skin metastasis from breast cancer involves a careful examination of the lesions followed by confirmatory tests to understand the extent of the spread and guide treatment decisions. Unlike some internal metastases that require imaging and complex tests, skin metastasis can often be seen directly, making diagnosis a little more straightforward in some ways. However, even with visible skin lesions, doctors still need to ensure they understand the full scope of the cancer’s behavior.

Clinical Examination

The first step in diagnosing skin metastasis is a thorough clinical examination. When you or your veterinarian (if the patient is a dog) notices a suspicious skin lesion, the doctor will examine the area closely to assess its size, texture, and boundaries. They’ll check whether the lesion is hard or soft, movable or fixed, and whether it’s ulcerated or inflamed. The location is also crucial, as metastases often appear near the original tumor site, but they can appear anywhere on the body.

In addition to visual inspection, doctors may also check for signs of lymphedema (swelling due to blocked lymphatic drainage), which can sometimes accompany skin metastases. This helps differentiate between a new metastasis and an infection or unrelated skin condition.

Biopsy

Once skin lesions are identified, the most important next step is a biopsy to confirm that the lesion is indeed metastatic breast cancer. The type of biopsy will depend on the lesion’s size and location:

- Punch biopsy: A small, circular instrument is used to remove a sample of the skin and underlying tissue. This is often done when the lesion is easily accessible, such as in an area with minimal hair or in an area the veterinarian can safely approach.

- Excisional biopsy: If the lesion is large or deeply embedded, doctors might remove the entire mass. This provides not only a diagnostic sample but also treatment for the lesion in some cases, as it can be an effective way to remove smaller, localized metastases.

A biopsy sample is sent to a pathologist, who will examine it under a microscope. The key to a definitive diagnosis lies in identifying cancer cells that resemble the original breast tumor. Pathologists also check for markers that can help classify the cancer and guide treatment decisions.

Imaging for Further Evaluation

Once a skin metastasis is diagnosed, imaging is often used to look for other potential metastatic sites. While skin metastases are accessible, they signal that the cancer may have spread to other parts of the body. Full-body imaging is typically the next step to check for additional tumors in deeper organs like the liver, lungs, or bones.

- CT scans or MRIs help doctors see internal tumors that can’t be felt or seen on the skin. These scans provide detailed images that help assess the full extent of metastasis.

- PET scans are another useful tool, particularly for detecting smaller or less obvious metastases that might not show up on CT or MRI scans. PET scans highlight areas of higher metabolic activity — typically where cancer cells are growing.

Staging the Disease

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, doctors need to stage the disease — determining how far the cancer has spread. This usually involves a combination of blood tests, imaging studies, and possibly biopsies from additional suspected sites. The goal is to understand not only where the cancer is located but also how aggressive it is, which will ultimately guide treatment options.

Staging is crucial because skin metastasis can indicate that the cancer has spread beyond the original site, which changes the treatment approach. It’s no longer just about treating a localized tumor; doctors now need to consider systemic treatments like chemotherapy, targeted therapies, or immunotherapy to address the entire body.

Next, we’ll dive into how metastatic breast cancer that spreads to the liver and skin is treated — discussing options from chemotherapy to radiation therapy, and the impact of new, cutting-edge treatments.

Part 7: How Breast Cancer Metastasis to Liver and Skin Is Treated

When breast cancer spreads to the liver or skin, the treatment approach becomes broader and more systemic. The primary goals shift from curing the disease to controlling it, extending survival, and maintaining the best possible quality of life. Treatments are often combined in flexible ways to match the cancer’s behavior and the patient’s needs.

Systemic Therapy

Because metastasis means cancer has traveled beyond its original site, systemic therapy is the foundation of treatment. These medications travel through the bloodstream to reach cancer cells wherever they might be.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a standard approach for many types of metastatic breast cancer. Drugs like doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel, and capecitabine work by targeting rapidly dividing cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy can shrink tumors, relieve symptoms, and sometimes extend survival significantly. Side effects vary but commonly include fatigue, nausea, temporary hair loss, and low blood cell counts, requiring careful management.

Targeted Therapy

For breast cancers that overexpress the HER2 protein, targeted therapies like trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab (Perjeta) are game-changers. These treatments specifically block signals that promote cancer growth, slowing or halting disease progression. Other targeted therapies may focus on stopping blood vessel formation (angiogenesis) that tumors rely on to grow.

Hormone Therapy

For patients whose cancer is hormone receptor-positive, hormone therapies remain crucial. Drugs like tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (such as letrozole or anastrozole) work by blocking estrogen, which many breast cancers depend on for growth. Hormone therapy tends to cause fewer harsh side effects than chemotherapy, making it a valuable option for long-term disease management.

Immunotherapy

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which lacks hormone receptors and HER2 expression, has fewer traditional treatment options but may respond to immunotherapy. Drugs like pembrolizumab (Keytruda) activate the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells. When combined with chemotherapy, immunotherapy can significantly improve outcomes for some patients with metastatic TNBC.

Liver-Directed Treatments

While systemic therapy is primary, sometimes doctors use treatments aimed directly at liver metastases when the spread is limited.

Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT)

SBRT delivers very high doses of targeted radiation directly to liver tumors while sparing nearby healthy tissue. It’s particularly useful for a small number of liver metastases (oligometastatic disease) and can provide effective local control.

Liver Ablation or Embolization

In selected cases, doctors may use ablation (destroying tumors with heat or cold) or embolization (blocking the blood supply to tumors) to treat liver lesions. These procedures are less common for breast cancer but can help control isolated liver metastases, especially when surgery is not an option.

Skin-Directed Treatments

Skin metastases often cause visible symptoms and discomfort, making local treatments a key part of management.

Radiation Therapy

External beam radiation can be used to shrink skin lesions, reduce pain, and control ulcerations. It’s especially helpful when lesions are bleeding, infected, or causing significant discomfort.

Topical Chemotherapy

For superficial lesions, topical chemotherapy agents like 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) can be applied directly to the skin. This approach offers a way to treat localized tumors with fewer systemic side effects.

Surgical Excision

When skin metastases are isolated and small, surgical removal may be possible. Surgery offers the dual benefit of diagnosing and treating the lesion, though it’s rarely curative in metastatic disease.

Palliative Care

Palliative care becomes increasingly important in metastatic breast cancer, not as a last resort but as an essential component of good medical care.

Pain Management

Pain from liver tumors or ulcerated skin lesions can be managed with medications ranging from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to opioids. Palliative radiation is also an option for painful bone or skin lesions.

Wound Care

Ulcerated or bleeding skin metastases require attentive wound care. Specialized dressings, gentle cleaning, and sometimes topical antibiotics help prevent infection and maintain comfort.

Nutritional Support

Patients dealing with liver metastases often experience weight loss, reduced appetite, or digestive issues. Nutritionists can offer dietary strategies and supplements to help maintain strength and energy.

Combining Approaches

In practice, treatments are rarely used in isolation. A patient might receive chemotherapy combined with targeted therapy, radiation for skin lesions, and palliative care interventions all at once. The goal is to match the treatment plan to the patient’s unique situation, balancing disease control with quality of life.

Now that we’ve explored how metastatic breast cancer is treated once it reaches the liver and skin, let’s take a closer look at what these diagnoses mean for prognosis — and how survival expectations have changed with newer therapies.

Part 8: Prognosis After Breast Cancer Spreads to the Liver and Skin

When breast cancer spreads to distant parts of the body — the liver, the skin, or both — it marks a serious turn in the disease. Yet prognosis is not a one-size-fits-all statement. Some patients live for many years after a metastatic diagnosis, while others face a faster course. The difference lies in several key factors: the biology of the cancer, the extent of the spread, how the body responds to treatment, and the overall health of the person facing the disease.

The Role of Cancer Subtype

The type of breast cancer makes a powerful difference. Hormone receptor-positive cancers tend to grow more slowly and respond well to hormonal therapies like tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. Patients with this kind of cancer often live for several years after metastasis is diagnosed, particularly if the disease stays sensitive to endocrine treatment. HER2-positive breast cancers, once feared for their aggressive behavior, now have far better outcomes thanks to targeted drugs like trastuzumab (Herceptin) and pertuzumab (Perjeta). Many people with HER2-positive metastatic disease live stable, full lives for years. By contrast, triple-negative breast cancers, which lack both hormone receptors and HER2 expression, remain among the most difficult to control. Survival times are shorter on average, but even here, new combinations of chemotherapy and immunotherapy are beginning to change the picture for some patients.

How the Extent of Spread Changes Outlook

Where the cancer has spread matters as well. Limited metastasis — a few spots in the liver, a small number of skin nodules — offers a better chance for durable control. Treatments like systemic therapy, radiation, and sometimes even surgery can manage small metastatic burdens very effectively. However, widespread disease, with many liver lesions or extensive skin involvement, usually signals a tougher battle ahead. It’s not only the number of metastases that counts, but also how well the liver continues to function. The liver is essential for life; once its capacity becomes overwhelmed by cancer, symptoms like jaundice, fluid buildup, and serious fatigue can emerge quickly.

The Importance of Treatment Response

Response to treatment is another critical factor. Some tumors respond dramatically to chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy, shrinking away on scans and giving patients months or even years of reprieve. Others prove more resistant, growing despite multiple lines of treatment. Sometimes doctors can switch strategies, moving from hormone therapy to chemotherapy or introducing clinical trial options, but not every cancer cooperates, and not every body tolerates repeated treatments equally.

How Age and Health Impact Survival

Age and general health add still more variables. A younger, otherwise healthy patient can usually withstand more aggressive therapy and recover better from its side effects. Older patients, or those with other illnesses like diabetes or heart disease, may find that the treatments themselves carry significant risks, narrowing the range of realistic options.

Survival Rates and Real-World Expectations

Survival statistics offer a rough guide but can never predict the future for any one individual. On average, patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer live around four to five years after metastasis is diagnosed, and many live longer. HER2-positive patients, thanks to modern therapies, often reach similar or better survival ranges. For triple-negative disease, median survival remains closer to one to two years, although individual outcomes vary widely, especially when newer immunotherapies are used early.

Patients with skin-only metastasis — where no internal organs are yet involved — may enjoy even longer survival. Skin lesions are visible, accessible for treatment, and slower to cause life-threatening complications compared to deep organ spread. On the other hand, extensive liver involvement tends to foreshorten survival, depending heavily on how much liver function remains intact and how well systemic therapy controls the disease.

None of these numbers erase the unpredictability or individuality of each case. Modern metastatic breast cancer treatment increasingly focuses not just on fighting the disease but on supporting life itself: managing pain, preserving function, maintaining emotional well-being, and creating space for joy, even in the face of serious illness. Many patients with metastatic disease continue to work, travel, celebrate milestones, and live fully for years, despite the shadow of cancer. Others face a steeper climb. Either way, survival statistics should be viewed as markers on the map — not as the road itself.

Now that we’ve laid out the real-world expectations, let’s turn to some of the questions patients and families most often ask when they first hear that breast cancer has spread to the liver or skin.

Part 9: FAQs About Breast Cancer Metastasis to Liver and Skin

Hearing that breast cancer has spread often triggers an avalanche of questions. Some of them are medical — about survival, treatment, and what to expect. Others are practical: how symptoms show up, how treatment decisions are made, whether certain signs are worrying. And some questions come straight from the heart, as patients and families try to navigate the emotional realities that no statistic or scan can fully capture.

Here, we’ll walk through some of the most common questions patients and families ask after a diagnosis of liver or skin metastasis — offering straightforward, human answers without false promises or unnecessary fear.

How long can you live with breast cancer that has spread to the liver?

There’s no single answer that fits everyone, but modern treatments have pushed survival times far beyond what they used to be. Some patients, especially those with hormone receptor-positive or HER2-positive cancers, live several years after liver metastasis is diagnosed. Response to treatment matters enormously. When the cancer responds well to systemic therapies — chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted drugs — patients can often enjoy long periods of stable disease. Even when complete remission isn’t possible, slowing the disease’s progression allows people to live meaningful, active lives. However, extensive liver involvement, rapidly growing tumors, or poor treatment responses can shorten survival significantly. Doctors focus not only on fighting the disease but also on preserving liver function and preventing complications that can impact quality of life.

Can skin metastases from breast cancer be mistaken for a rash?

Yes — and unfortunately, they often are at first. Skin metastases can appear as red, raised areas that mimic infections, allergic reactions, or even benign skin conditions. They might look like a rash, an inflamed scar, or a patch of thickened skin. Sometimes they feel firm or rubbery under the surface. Because early skin metastases don’t always hurt or bleed, they’re easy to dismiss — especially if they show up near a prior surgery or radiation site where the skin was already altered. If any new skin changes appear in a person with a history of breast cancer, even if they seem minor, they should be evaluated quickly by a doctor.

Does liver metastasis always cause symptoms?

Not always — and that’s part of what makes it dangerous. Many patients have no obvious symptoms when liver metastases first appear. Even as tumors grow, the liver’s remarkable ability to compensate can mask trouble for a long time. Symptoms like fatigue, vague abdominal discomfort, or mild nausea are easy to overlook or attribute to less serious problems. It’s often only when liver function begins to falter — causing jaundice, swelling, pain, or itching — that the metastasis becomes undeniable. That’s why routine monitoring through blood tests and imaging is so important for breast cancer survivors, even when they feel perfectly well.

Can metastases shrink or disappear with treatment?

They can — and it happens more often than people might think. Many systemic treatments are designed to shrink metastases significantly, and in some cases, tumors can become undetectable on scans for months or even years. Chemotherapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy all have the potential to induce substantial responses. However, most doctors talk about “control” rather than “cure” when treating metastatic disease. Even when metastases shrink or disappear from imaging, microscopic cancer cells often remain, requiring ongoing treatment or close monitoring to keep the disease in check.

How is treatment different if only the skin is involved, not internal organs?

When metastasis is limited to the skin, treatment options often expand. Doctors may still recommend systemic therapy to address any unseen cancer cells elsewhere in the body, but local treatments like surgery, radiation, or topical chemotherapy become more practical. Skin lesions can sometimes be excised or radiated with good results, especially if they’re isolated and small. Managing skin-only metastases can significantly delay progression to deeper organ involvement. The prognosis for skin-only spread is generally better than for visceral metastases, although ongoing vigilance remains essential.

Closing the FAQs

Questions don’t stop once the first wave of shock wears off. They evolve over time, just like the disease itself. New treatments emerge, side effects appear and disappear, decisions about next steps arise. Having a trusted care team, open channels for asking questions, and solid, understandable information makes a profound difference in how patients and families weather the journey. There’s no such thing as a silly or unimportant question when it comes to facing breast cancer — especially once it steps beyond the breast and into the wider body.

As we close this discussion, let’s take a moment to focus on what truly matters: finding ways to live meaningfully, courageously, and fully, no matter what shape the path ahead takes.

Part 10: Final Thoughts

When breast cancer spreads to the liver or skin, life changes. There’s no getting around it. The road ahead can feel uncertain, frightening, and at times overwhelming. Yet alongside all of that, many people also find resilience they didn’t know they had — a fierce determination to live, to hope, and to shape the time they have in ways that matter.

Metastatic breast cancer today is not what it was a decade ago. Treatments are better. Outcomes are longer. Even when cure isn’t possible, many patients live months or years beyond their diagnosis, finding new rhythms of life, new goals, and often a new sense of what truly matters most. Medical advances — from targeted therapies to immunotherapies — continue to push survival farther with every passing year. While statistics offer a glimpse at broad patterns, they don’t define any one person’s path. Biology, treatment choices, response to therapy, support networks, and pure individual will all weave together to create a story that no scan or lab result can fully predict.

Facing metastatic cancer doesn’t mean surrendering hope. It means living alongside uncertainty, sometimes fighting hard, sometimes resting, sometimes redefining success in ways that feel deeply personal. For some, success looks like shrinking tumors and achieving long periods of stable disease. For others, it looks like controlling symptoms, savoring time with loved ones, or reclaiming daily joys even in the midst of treatment.

Support makes a difference. Staying connected to skilled medical teams, reaching out for emotional help, asking questions, and advocating for the life you want are all powerful ways of reclaiming agency in a situation that often feels uncontrollable. Whether through clinical trials, new treatments, or simply the day-by-day commitment to keep moving forward, there are always ways to find meaning and purpose, even when the road turns rough.

If you or someone you love is facing breast cancer metastasis to the liver or skin, know this: the path ahead is yours to walk, but you do not walk it alone. Compassionate doctors, nurses, counselors, friends, family, and fellow survivors stand ready to walk beside you, every step of the way.