Ebola Virus Disease: Challenges in Containment and Treatment

Ebola Virus Disease: Why Does It Still Haunt Us?

Have you ever wondered how a virus can send entire regions into lockdown, overwhelm healthcare systems, and stir global panic within days? That’s exactly what Ebola virus disease (EVD) has done—more than once.

First identified in 1976 near the Ebola River in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, the virus quickly proved itself to be one of the deadliest pathogens known to humankind. But why does it still pose such a threat today, decades later?

Ebola isn’t just a medical issue. It’s also a crisis of trust, infrastructure, and timing. When outbreaks occur, they strike fast and hard—often in areas where medical resources are limited and public health messaging struggles to keep pace. Have you ever considered how a lack of local hospitals or clean water could be just as deadly as the virus itself?

In many ways, the public health response to Ebola shares similarities with the challenges posed by Oropouche Fever—another outbreak-prone illness where delayed detection and local infrastructure gaps compound the crisis.

Looking back at major outbreaks—like the 2014–2016 West African epidemic that killed over 11,000 people—what can we learn from the past? Were the delays in response purely logistical, or was there a deeper failure in communication and preparedness?

In this series, we’ll explore the virus from multiple angles: What exactly makes Ebola so deadly? How does it travel and who is most at risk? And—most importantly—what are we doing to stop it from spreading again?

Whether you’re coming to this topic with a scientific lens or just a general curiosity, this journey through the world of Ebola might challenge your assumptions. How much progress have we really made—and what still stands in the way?

Let’s start at the molecular level in Part Two: Virology and Pathogenesis. What’s going on inside this tiny killer?

Virology and Pathogenesis

What Makes the Ebola Virus So Dangerous on a Microscopic Level?

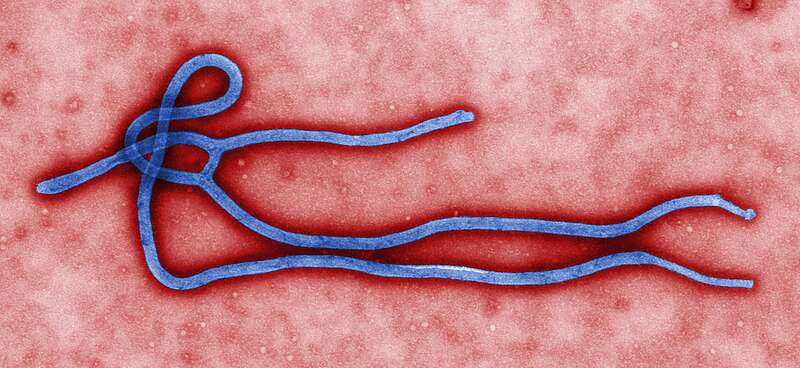

So, what exactly is Ebola? It’s not just a name that sparks fear—it’s a filovirus, a type of virus known for its long, threadlike shape. That shape isn’t just unusual, it’s part of what makes Ebola so efficient at invading human cells. But let’s dig deeper: how does something so small cause so much devastation?

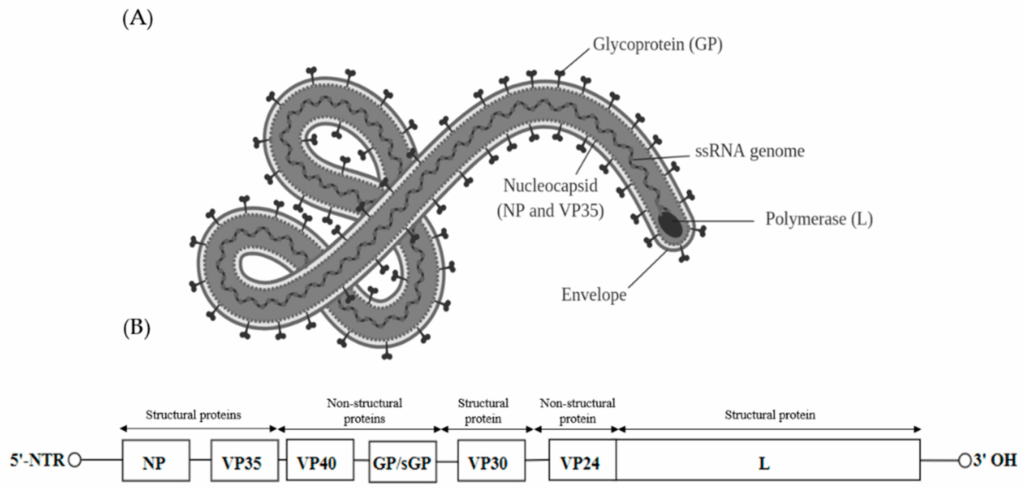

The Ebola virus is made up of a few essential parts: a single strand of RNA, a protective protein coat, and a handful of specialized proteins that help it hijack the human immune system. Sounds simple, right? But it’s disturbingly effective. The RNA carries the genetic instructions the virus needs to replicate. Meanwhile, surface proteins act like keys, unlocking our cells so the virus can slip inside unnoticed.

One question that scientists have wrestled with for years is: how does the virus manage to dodge our immune system for so long? Normally, when a pathogen invades, our body sounds the alarm almost immediately. But Ebola can suppress and delay this response. It blocks the release of interferons—chemical signals that help marshal the body’s defenses—allowing it to spread stealthily before the immune system fully catches on.

And once the virus has entered a host cell? It turns that cell into a viral factory, churning out thousands of copies until the cell bursts. This process doesn’t just destroy tissues—it causes a sort of immune overreaction, like a fire alarm going off in every room of a building all at once. Cytokine storms, vascular leakage, hemorrhaging… these aren’t just symptoms, they’re biological chaos.

Another eerie question: Why does Ebola cause bleeding? Not all patients bleed, but when it happens, it’s because the virus attacks the cells lining the blood vessels, causing them to break down. It also disrupts blood clotting mechanisms, pushing the body toward uncontrollable internal and external bleeding. It’s not a Hollywood exaggeration—this can and does happen, especially in severe cases.

Is it possible to predict which patients will get hit the hardest? Scientists are still piecing together that puzzle. Factors like viral load, host genetics, and immune health all seem to play a role, but we don’t have a perfect map yet.

Ultimately, the terrifying power of the Ebola virus lies in its simplicity. No brain, no motive—just a relentless biological machine. And yet, it’s brilliant at outwitting our defenses. Doesn’t that raise an unsettling question—if something so tiny can outsmart us, how can we ever truly be ready?

We covered related information on Oropouche Fever in another article titled “Oropouche Fever”.

In the next part, we’ll zoom out from the microscopic level and look at the bigger picture: Where does Ebola appear, how does it spread, and why do outbreaks seem to emerge in some regions more than others?

Epidemiology

Where Does Ebola Strike — and Why There?

When we hear about an Ebola outbreak, it’s almost always tied to a specific place. But have you ever wondered why Ebola tends to emerge in certain parts of Africa, and not—say—Europe or North America? Is it just chance, or is there something deeper going on?

Ebola virus disease has primarily affected countries in Central and West Africa. Places like the Democratic Republic of Congo, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone have experienced some of the most devastating outbreaks. But why these regions? Part of the answer lies in ecology—and part of it in infrastructure.

Let’s start with nature. Ebola is a zoonotic disease, meaning it spills over from animals to humans. But who are the usual suspects in this viral game of tag? Bats—particularly fruit bats—are believed to be the natural reservoir of the Ebola virus. They can carry the virus without getting sick, and they often live in close proximity to humans and other animals, especially in rural or forested areas.

So imagine a hunter in a remote village butchering a bat or another infected animal. What seems like a normal act of subsistence suddenly becomes the spark of an outbreak. How often does that happen? Surprisingly, spillover events might be more common than we think—many are just caught early or fade out before spreading.

But once a human infection begins, what determines whether it becomes an epidemic? That’s where social and healthcare factors kick in. Lack of access to hospitals, understaffed clinics, limited clean water, and poor communication systems all make it harder to identify, isolate, and treat Ebola cases quickly.

And what about human behavior? Funeral traditions, for instance, can unintentionally spread the virus. In some cultures, it’s customary to wash and touch the deceased as a sign of respect. But with Ebola, the bodies remain highly infectious after death. It’s a heartbreaking intersection of tradition and biology. How do you balance honoring culture with preventing catastrophe?

Ebola spreads through direct contact with the bodily fluids of infected individuals—blood, vomit, saliva, sweat, even breast milk or semen. It’s not airborne in the way that, say, the flu or COVID-19 is. So you might ask: Why is it so hard to stop if it’s not airborne? The answer lies in timing. People are usually most infectious when they’re already very sick, which means caregivers—often family members or healthcare workers—are directly in the line of fire.

Let’s not forget mobility. In an interconnected world, even remote areas aren’t as isolated as they once were. Roads, markets, and cross-border travel can all accelerate the spread. During the 2014–2016 outbreak, the virus leapt across three countries in just a matter of weeks.

So, if we can map these patterns, can we predict or even prevent the next outbreak? That’s the hope—but predicting nature is never easy.

In the next part, we’ll explore what happens once someone actually gets sick. What does Ebola look like in the body, and how does it unfold from day one to the critical point?

Clinical Features

What Does Ebola Feel Like — and How Does It Progress?

If you were exposed to the Ebola virus today, would you feel anything right away? Probably not. That’s part of the challenge. Ebola starts silently. There’s an incubation period—usually between 2 to 21 days—where you might feel perfectly fine. But behind the scenes, the virus is already at work.

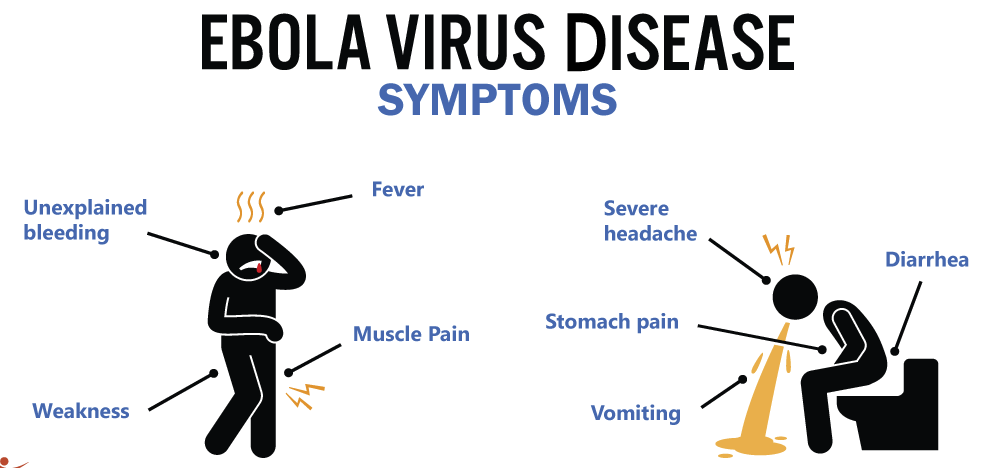

So what’s the first sign that something’s wrong? Most people start with what feels like a very bad flu: sudden fever, headache, muscle pain, and fatigue. But here’s the catch—how do you tell Ebola apart from malaria or even a bad cold at this stage? You can’t, not without testing. That’s one reason outbreaks can spread before anyone realizes what’s happening.

Then the illness shifts. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea often set in. These symptoms aren’t just unpleasant—they’re dangerous. Severe fluid loss leads to dehydration and imbalances in electrolytes, weakening the body further. At this point, the virus is attacking internal organs, especially the liver and kidneys. You might wonder: Is this when it becomes life-threatening? The answer is yes—if left untreated, this phase can quickly become fatal.

One of the most well-known and terrifying signs of Ebola is hemorrhaging. But here’s something you might not know: not everyone bleeds. In fact, bleeding occurs in only a subset of patients—often those with the most severe disease. When it does happen, it can range from small bruises or bloody gums to more dramatic signs like vomiting blood or internal bleeding. Why does the body unravel this way? It’s because the virus disrupts clotting systems and causes blood vessels to leak.

Another question: Why do some people survive while others don’t? That’s a mystery scientists are still working to solve. Some studies suggest that people with strong, early immune responses may fare better. Others point to viral load—how much virus is in the bloodstream—as a predictor. But there’s no single answer yet.

The case fatality rate for Ebola can range from 25% to over 90%, depending on the outbreak and the strain. That’s not just high—it’s staggering. But survival also hinges on access to care. With aggressive hydration, close monitoring, and supportive treatments, survival rates improve dramatically.

In recent years, experimental therapies and better supportive care have lowered fatality rates in some outbreaks—but only when healthcare systems can deliver them in time. It’s a dynamic not unlike what we’ve seen with Ascites treatment strategies, where timing, resource availability, and systemic support make all the difference in outcomes.

One haunting feature of Ebola is how deeply it can affect the body—even after recovery. Some survivors continue to experience joint pain, vision problems, fatigue, or even mental health issues for months. The virus has even been found lingering in certain parts of the body—like the eyes and testes—long after the person appears to have recovered. This raises difficult questions: Can someone relapse? Could they still transmit the virus weeks or months later? In rare cases, yes.

Understanding the clinical features of Ebola isn’t just about the science—it’s about empathy. Every statistic represents a person going through something unimaginably difficult, often in the most resource-limited settings. And when caregivers get sick too, it becomes not just a personal battle, but a community crisis.

Next, we’ll ask a critical question: How do doctors actually diagnose Ebola—and why is early detection so crucial to stopping it in its tracks?

Diagnosis

How Do You Confirm Ebola — and Why Is Timing Everything?

If someone walks into a clinic with a fever, headache, and muscle pain, what’s the first thought? Probably not Ebola. In many of the regions where outbreaks occur, malaria or typhoid is far more common. So here’s the big question: How do you know it’s Ebola before it’s too late?

Diagnosis is one of the trickiest parts of managing Ebola outbreaks. In the early stages, symptoms overlap with dozens of other illnesses. That’s why lab testing is absolutely essential. But here’s the catch—many of the areas where Ebola appears are also areas with very limited laboratory infrastructure. So what happens when the nearest testing lab is hundreds of miles away?

Traditionally, confirmation has come through RT-PCR testing—short for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. It’s a mouthful, but the idea is pretty straightforward: this test looks for pieces of the virus’s genetic material in a patient’s blood. If it finds them, you’ve got a confirmed case. It’s accurate and reliable—but also slow and technology-heavy. Not ideal in the middle of a rural outbreak.

That leads to another big question: What if we could diagnose Ebola right there at the patient’s bedside? Enter point-of-care diagnostics. These are rapid tests that can be performed in the field, often without electricity or advanced lab equipment. They’re faster—sometimes giving results in under an hour—and while they’re not quite as accurate as PCR, they’re good enough to guide urgent decisions.

But here’s where the story gets more complicated. Even with testing, there’s a time lag between infection and detectability. If someone is tested too early—before the virus builds up in the blood—they might get a false negative. That means healthcare workers often need to test again later if symptoms continue. It’s a race against the clock, and the virus isn’t known for being patient.

So why does early detection matter so much? Because Ebola spreads through direct contact with bodily fluids, identifying and isolating cases early can mean the difference between a contained outbreak and a runaway epidemic. Every hour counts. Once someone is diagnosed, a whole cascade of actions can begin—contact tracing, isolation, protective equipment, and community alerts.

There’s also the emotional side. What does it feel like to be tested for Ebola? For many people, it’s terrifying. Testing positive can mean weeks of isolation, stigma, and in some cases, separation from family and children. In communities that have experienced multiple outbreaks, there’s sometimes distrust toward health authorities. People might avoid testing altogether, fearing what it will mean.

So how do we balance accuracy, speed, and accessibility in Ebola diagnostics? That’s a question researchers and public health workers are still working to answer. The ideal tool would be fast, reliable, portable, and cheap—and we’re getting closer. Some newer tests, like isothermal amplification assays and antigen-based kits, show promise. But as of now, no single test checks every box.

At the end of the day, the goal is simple but urgent: identify and isolate the virus before it spreads. That starts with awareness—but depends on access.

Next, we turn from diagnosis to what comes after: Once someone is confirmed to have Ebola, what treatment options are available—and are they enough?

Treatment

Once You Have Ebola, What Can Be Done — And Is It Ever Enough?

Imagine you’ve just been told you have Ebola. What’s the first thing that goes through your mind? Fear? Confusion? A racing thought: Is there a cure?

For a long time, the answer to that last question was bleak. There was no cure, no proven treatment—just supportive care. And while that sounds basic, it’s more powerful than it seems. But before we talk about cutting-edge therapies, let’s ask: What does “supportive care” actually mean when you’re fighting one of the deadliest viruses known to humans?

Supportive care means keeping the body alive while the immune system fights the virus. That includes IV fluids to combat dehydration, electrolyte balancing, oxygen, medications to control fever, vomiting, and pain—and, in severe cases, treating complications like organ failure. In the right setting, this kind of care can drastically improve survival. The catch? It requires resources, training, and time—three things in short supply during most Ebola outbreaks.

But the tide began to turn in recent years. Thanks to global urgency following the 2014–2016 West Africa outbreak, researchers pushed harder than ever to find targeted treatments. That leads us to a hopeful question: Are there now drugs that can actually fight the virus directly?

Yes. In 2019, a clinical trial during an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo tested several experimental treatments head-to-head. Two of them—REGN-EB3 (a monoclonal antibody cocktail) and mAb114—showed clear benefit, especially when given early. These treatments work by giving the immune system a boost, offering lab-made antibodies that neutralize the virus. It’s like handing the body a weapon it didn’t have time to make on its own.

So if we have effective therapies now, why do people still die from Ebola? Timing is everything. These treatments work best when given early, before the virus overwhelms the body. In many outbreaks, patients arrive at care centers too late—or care centers are too far away to reach in time. There’s also the challenge of delivering these therapies safely, especially when healthcare workers are stretched thin and personal protective equipment is in short supply.

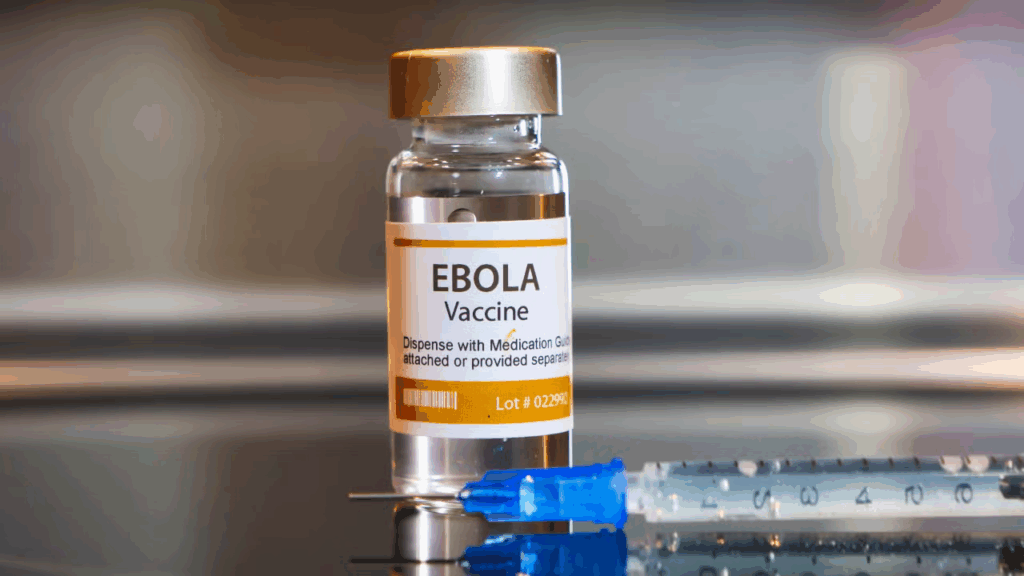

But here’s some real progress: vaccines. The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, also known as Ervebo, became a game-changer after proving its ability to prevent infection. It’s a live, attenuated vaccine that uses a harmless virus to deliver a key Ebola protein, teaching the body to defend itself. Deployed in a “ring vaccination” strategy—vaccinating contacts and contacts of contacts—it’s helped contain multiple outbreaks. How powerful is that? We’ve gone from helpless to proactive.

And more vaccines are in the pipeline, including candidates that could protect against multiple strains of Ebola and even other filoviruses. The goal is to stay ahead of the virus—not just react to it.

But no matter how good the science gets, one question lingers: Can we get these treatments and vaccines to the people who need them most, fast enough? That depends not just on medicine, but on politics, logistics, and trust. A miracle drug means little if it can’t reach the village in time.

So yes, we have tools now—real tools. But the battle is still uphill. Next, we’ll look at how outbreaks are contained in the real world: What does it take to prevent Ebola from spreading, and how do communities play a role in that fight?

Prevention and Control

How Do You Stop a Virus Like Ebola — and Can Communities Really Make the Difference?

So let’s say a case of Ebola is confirmed in a small town. What happens next? Do medical teams rush in with hazmat suits? Do borders close? Do people run, hide, or help? The reality is, every outbreak plays out a little differently—but one thing is always true: stopping Ebola is never just about medicine. It’s also about people.

Let’s start with the obvious: infection control in healthcare settings. You’ve probably seen those striking images—doctors and nurses wrapped in layers of protective gear, face shields fogged with breath. It looks dramatic, but it’s essential. The virus is so infectious in bodily fluids that even a small mistake—one glove torn, one contaminated needle—can be fatal.

So here’s a blunt question: How do you treat patients with a deadly virus without risking your own life? The answer is strict protocols: isolation rooms, disinfection procedures, dedicated staff, and lots of training. But in under-resourced clinics, that’s easier said than done. Sometimes, it’s not a lack of knowledge that spreads Ebola—it’s a lack of gloves, bleach, or even clean water.

But hospitals aren’t the only battleground. Ebola thrives when fear and misinformation spread faster than the virus itself. In past outbreaks, rumors have led communities to hide the sick, flee quarantine zones, or even attack health workers. So that raises a deeper question: What happens when people don’t trust the people trying to help them?

That’s why community engagement is just as critical as any vaccine. Health responders can’t just arrive with syringes and science—they need to listen, learn, and adapt. What do people understand about the disease? What do they fear? How can life-saving information be shared in a way that respects local culture?

Sometimes it means working with village elders, religious leaders, or traditional healers. Sometimes it means adjusting burial practices in ways that preserve dignity while protecting the living. If people understand why something is happening—and if they feel part of the solution—they’re far more likely to cooperate. Would you let a stranger take your loved one’s body away without explanation? Most people wouldn’t. That’s why communication is everything.

Then there’s contact tracing, a behind-the-scenes tool that’s surprisingly powerful. Think of it like detective work: for every confirmed case, a team works to find everyone that person may have been in contact with. Then they monitor those contacts for signs of illness. If done thoroughly and quickly, this method can stop an outbreak in its tracks. But it’s labor-intensive, and in areas with little infrastructure, it becomes a logistical nightmare.

And what about travel restrictions, lockdowns, or border screenings? They can help slow the spread, but they come with trade-offs—economic damage, social disruption, and even panic. So the question becomes: How do you strike the right balance between containment and compassion?

Finally, there’s the role of international cooperation. Ebola doesn’t respect borders, so neither can the response. Organizations like WHO, MSF, and the CDC often work side by side with local health ministries, but coordination takes time—and trust. The faster that trust is built, the more lives are saved.

Ebola may be a biological threat, but stopping it is a human story—of courage, of learning, of showing up despite the danger.

Next, we’ll look at the most recent chapters of that story: What’s happened with Ebola in the last year or two, and are we any closer to ending these outbreaks for good?

Recent Developments (2025–2026)

Is the Tide Finally Turning on Ebola — or Are We Still Playing Catch-Up?

After decades of devastation, you might ask: Are we any closer to closing the chapter on Ebola? The answer, cautiously, is maybe. The past couple of years have brought real progress—but also some reminders that this virus isn’t going quietly.

Let’s start with the good news. In 2025, a new multivalent vaccine entered early deployment. What does that mean? Unlike earlier vaccines that targeted a single Ebola strain (like the Zaire strain), this one is designed to protect against multiple types—including the rarer Sudan strain, which caused a worrying outbreak in Uganda in 2022. That raises a hopeful question: Could we finally be building tools to outpace the virus, not just react to it?

These new vaccines are part of a broader push toward preemptive vaccination—not just vaccinating in response to outbreaks, but preparing high-risk communities in advance. Think of it like fireproofing before the flames. In 2025, pilot programs in parts of West Africa began immunizing healthcare workers and frontline responders preemptively, even before any cases appeared. That’s a huge shift in strategy—and one with real promise.

But progress doesn’t mean perfection. In late 2025, a small outbreak in a border region between the DRC and South Sudan flared unexpectedly. Despite improvements in detection, response teams struggled to reach the area quickly due to conflict and flooding. By the time the first case was confirmed, several others had already slipped through to neighboring towns. It’s a painful reminder that technology can only go so far when geography and politics get in the way.

And here’s something you might not expect: researchers are now studying Ebola virus persistence more closely than ever. In a handful of cases, the virus has re-emerged in survivors—sometimes months after they were declared Ebola-free. How? It turns out the virus can hide in certain immune-privileged sites, like the eyes, brain, or testes. That’s led to new protocols for follow-up testing, counseling, and even longer-term survivor monitoring. Could the next outbreak start from a “survivor spark”? It’s rare, but it’s happened—and it’s reshaping our understanding of what recovery really means.

On the treatment front, 2025 also saw the approval of a portable infusion kit for administering monoclonal antibody therapy in field settings. It’s lighter, faster to deploy, and doesn’t require advanced electricity or refrigeration—making it a potential game-changer in rural outbreaks. But again, will we get it where it’s needed most in time? That’s the operational challenge.

As we consider how viral threats shift and adapt, it’s worth noting how lessons from H1N1’s evolving drug resistancecontinue to inform our approach to mutation monitoring, contingency planning, and pre-deployment of therapies.

So are we winning the fight? We’re certainly better armed, better trained, and more aware. But Ebola is not just a virus. It’s a test of systems—health systems, political systems, community resilience, and global will.

In the final part, we’ll ask the biggest question of all: What still stands in our way—and what will it really take to make sure the next generation never has to fear Ebola again?

FAQ: Ebola Virus Disease — What People Are Asking

1. Why does Ebola still pose a threat after all these years?

Despite decades of research, Ebola continues to resurface in regions with limited healthcare infrastructure, ecological risk factors, and delayed responses. Its ability to spread rapidly and evade early detection keeps it dangerous.

2. How does something so small cause so much destruction in the human body?

The Ebola virus hijacks cells, disables immune responses, and triggers massive inflammation, organ damage, and in some cases, internal bleeding. Its simplicity is part of what makes it so lethal.

3. Why do outbreaks only seem to happen in certain places?

Geography, wildlife ecology (especially bats), and local healthcare capacity all contribute. Spillover events from animals to humans tend to happen in remote or forested areas with limited surveillance.

4. What makes it so hard to spot Ebola early?

Early symptoms mimic many common illnesses—fever, headache, muscle pain—so it’s often misdiagnosed. Without lab testing, Ebola can spread before anyone realizes it’s even there.

5. Why do only some people with Ebola bleed?

Bleeding is a sign of severe disease. The virus disrupts the body’s ability to clot and damages blood vessel linings, but not every patient reaches that stage.

6. Can you survive Ebola?

Yes—especially with early diagnosis, aggressive supportive care, and access to newer treatments. But outcomes depend heavily on timing and healthcare access.

7. How is Ebola actually diagnosed?

RT-PCR tests are the gold standard, but point-of-care rapid tests are increasingly available. Testing too early can lead to false negatives, so timing matters.

8. Are there any real treatments now?

Yes. Monoclonal antibody therapies like REGN-EB3 and mAb114 have been shown to reduce mortality, especially when given early. Supportive care also remains essential.

9. Can Ebola survivors still carry or spread the virus?

In rare cases, yes. The virus can persist in immune-privileged areas of the body for months, sometimes leading to delayed complications or even relapse.

10. How do you stop an outbreak once it starts?

Through a combination of infection control, contact tracing, vaccination, community engagement, and trust-building. Outbreaks are stopped not just with science, but with people.

11. Are vaccines making a real difference?

Absolutely. The Ervebo vaccine and newer multivalent vaccines are changing the game, especially when deployed quickly in ring vaccination strategies or as preventive tools.

12. Is there hope for the future?

Yes—if we continue investing in local capacity, early warning systems, equitable distribution of treatments, and ongoing research. We’re closer than ever, but not finished yet

Conclusion

What Will It Take to End Ebola — For Good?

Ebola isn’t just a virus—it’s a mirror. It reflects how prepared we are, how connected we are, and how we treat those on the margins. Every outbreak tells a story, not just of biology, but of systems under stress: healthcare networks stretched thin, communities isolated by geography or mistrust, and the fragility of global cooperation when time is short.

So where do we go from here?

We know more about the virus now than ever before. We have vaccines that work, therapies that save lives, and diagnostic tools that can flag the disease early. That’s remarkable progress. But knowledge doesn’t stop outbreaks—action does. And action needs investment, equity, coordination, and—above all—trust.

Ending Ebola isn’t about eradicating a virus in a lab. It’s about building strong, resilient systems that can detect a threat early, respond quickly, and protect everyone—especially those living where the next spark might ignite.

It’s a long road. But for the first time, we’re walking it with a map.