Does a PET Scan Show Colon Cancer? A Professional Insight for Early and Advanced Detection

- Understanding PET Scans: Basic Principles and Mechanisms

- The Role of PET Scans in Diagnosing Colon Cancer

- PET vs. Other Imaging Modalities in Colon Cancer Evaluation

- Clinical Indications: When a PET Scan Is Recommended in Colon Cancer

- Sensitivity and Specificity of PET in Detecting Colon Cancer

- Limitations of PET Scans in Colon Cancer Imaging

- Preparing for a PET Scan: Patient Instructions and Considerations

- PET Imaging for Surveillance After Colon Cancer Treatment

- The Use of PET in Staging Colon Cancer

- Differentiating Between Scar Tissue and Active Cancer

- Interpreting PET Scan Results: What the Numbers Mean

- PET/CT Use Across Colon Cancer Stages

- PET Versus Colonoscopy: Different Tools for Different Questions

- PET’s Role in Guiding Surgical and Treatment Decisions

- Cost, Insurance, and Access Considerations for PET Imaging

- Future Directions in PET Imaging for Colon Cancer

- FAQ

Understanding PET Scans: Basic Principles and Mechanisms

How PET Imaging Works Inside the Body

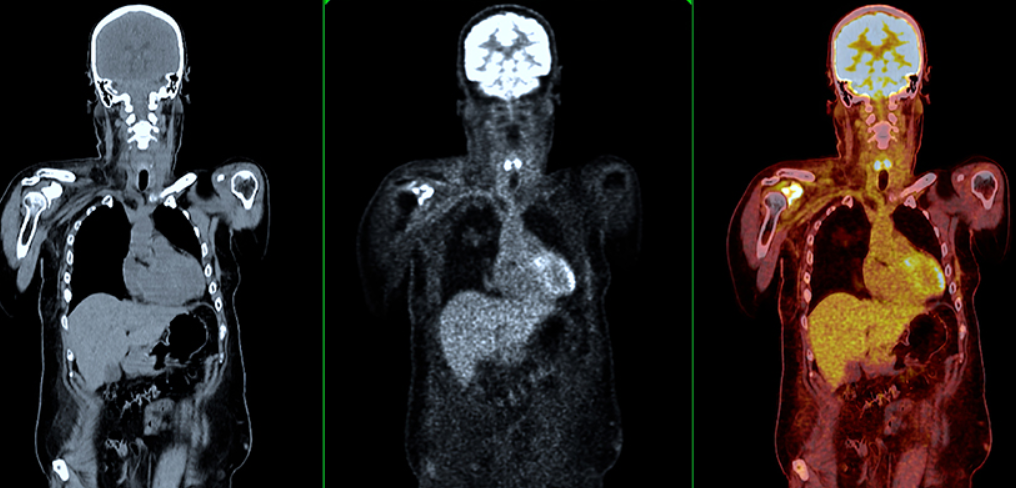

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) is a nuclear medicine imaging technique that measures metabolic activity at the cellular level. Unlike structural imaging methods such as CT or MRI, PET evaluates how tissues and organs function by detecting radiation emitted from a radioactive tracer, most commonly fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG). Cancer cells, including those found in colon cancer, often exhibit increased glucose metabolism, making them highly visible on a PET scan.

Once the radiotracer is injected into the patient’s bloodstream, it circulates and accumulates in tissues with high metabolic demand. A specialized PET scanner then captures this data and converts it into a three-dimensional image, revealing areas of abnormal activity. This process enables clinicians to differentiate between malignant tumors, inflamed tissues, and normal physiological processes. The combination of PET with CT (PET/CT) enhances both the anatomical detail and metabolic mapping, making it particularly valuable in oncology.

The Role of PET Scans in Diagnosing Colon Cancer

When and Why PET Is Used in Clinical Practice

Although PET scans are not typically the first-line tool for initial colon cancer screening, they play a crucial role in diagnosis under specific circumstances. Patients who present with ambiguous symptoms, previously inconclusive colonoscopy findings, or suspected recurrence may undergo PET scanning to obtain more detailed functional insights. PET scans can detect lesions that may not be visible on CT or MRI, particularly in metabolically active tumors or distant metastases.

In clinical oncology, PET is often reserved for staging and restaging colon cancer once the disease has been confirmed through colonoscopy and biopsy. The metabolic data obtained allows physicians to evaluate whether the tumor has spread beyond the colon, particularly to the liver, lungs, or lymph nodes. In this context, PET scanning is a valuable adjunct to anatomical imaging, rather than a replacement.

Moreover, there are rare cases where colorectal pathology may overlap with findings typical in other malignancies such as lewis lung cancer and T cell exhaustion, especially when immune-based treatments are being considered.

PET vs. Other Imaging Modalities in Colon Cancer Evaluation

Comparing PET with CT, MRI, and Ultrasound

To appreciate the full utility of PET in colon cancer, it’s important to compare it with traditional imaging methods. CT scans provide detailed cross-sectional anatomical views, allowing for precise localization of tumors. MRI excels in soft tissue differentiation, especially in the pelvis and liver. Ultrasound is often used in preliminary evaluations but lacks the resolution required for deeper organ analysis.

PET stands out for its metabolic perspective. While CT might show a mass, PET reveals whether that mass is metabolically active and potentially cancerous. This distinction is critical in assessing lymph node involvement or distinguishing scar tissue from active tumor post-treatment. However, PET is not infallible—it can generate false positives in cases of infection, inflammation, or certain benign growths that also show increased FDG uptake.

The best diagnostic outcomes are often achieved by combining modalities, particularly PET/CT, which integrates functional and structural data into a single, cohesive image. This synergy is now a standard in oncological imaging workflows for comprehensive evaluation and staging.

Clinical Indications: When a PET Scan Is Recommended in Colon Cancer

Tailored Use Based on Disease Stage and Clinical History

The recommendation for a PET scan depends heavily on a patient’s clinical profile. In early-stage colon cancer, PET is rarely indicated unless there is suspicion of synchronous tumors or uncertain findings on conventional imaging. It becomes far more relevant in later stages, especially stage III and IV, where assessing the full extent of metastasis is critical to determining treatment strategy.

Common clinical indications include:

- Confirming metastatic spread to organs such as the liver or lungs

- Identifying recurrence in patients with rising carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels but no clear findings on CT

- Guiding radiation planning in advanced cases

- Evaluating response to chemotherapy or immunotherapy regimens

Additionally, PET scans are sometimes utilized when symptoms suggest cancer recurrence but endoscopic or biopsy evidence is lacking. In these cases, PET helps visualize occult metastases that evade conventional imaging. This nuanced use of PET parallels the complex diagnostic approaches used in dermatologic cancers like early stage eyelid cancer pictures, where functional imaging can differentiate between benign and malignant changes.

Sensitivity and Specificity of PET in Detecting Colon Cancer

How Reliable Is PET in Identifying Primary and Metastatic Lesions?

The effectiveness of PET scans in detecting colon cancer is influenced by the biological behavior of the tumor and the location of the lesions. In terms of sensitivity—the ability to correctly identify patients with disease—PET scans perform well in detecting metabolically active metastatic colon tumors, especially in the liver, lungs, and lymph nodes. However, the sensitivity may decrease for small, early-stage primary tumors or mucinous subtypes, which tend to exhibit low FDG uptake.

Specificity, or the ability to distinguish cancerous lesions from benign conditions, can also vary. Inflammatory processes, infections, and benign tumors such as adenomas may show increased metabolic activity and produce false-positive results. Despite these limitations, studies have demonstrated that PET/CT offers an overall sensitivity of approximately 90% and specificity of 85% for metastatic colon cancer. When combined with other imaging and laboratory findings, PET becomes a powerful tool for guiding diagnosis and treatment.

Limitations of PET Scans in Colon Cancer Imaging

Recognizing Scenarios Where PET Is Less Effective

While PET scans are valuable in many oncology contexts, they are not without drawbacks. Their biggest limitation in colon cancer imaging is reduced accuracy in detecting low-grade tumors, mucinous adenocarcinomas, and small lesions under 1 cm. These types of tumors often do not consume glucose at high rates, resulting in minimal FDG uptake and false-negative scans.

Another concern is the interpretation of uptake in the bowel. The gastrointestinal tract naturally exhibits variable FDG activity due to peristalsis, mucosal inflammation, or even recent food intake, which can obscure or mimic tumor signals. Furthermore, the cost and availability of PET technology, particularly in resource-limited settings, may restrict access.

Additionally, some patients with comorbidities may not be ideal candidates for PET imaging. For example, individuals with renal impairment may struggle with tracer clearance, and certain diabetic patients may require glucose stabilization prior to the scan. These nuances must be carefully considered by the oncology team, just as they are in cases exploring less conventional veterinary oncology approaches, such as those described in alternative cancer treatments for dogs.

Preparing for a PET Scan: Patient Instructions and Considerations

What to Expect Before and During the Procedure

Preparation for a PET scan is critical for obtaining accurate and meaningful results. Patients are usually instructed to fast for at least 4 to 6 hours prior to the scan to minimize non-specific glucose uptake. Water is permitted and even encouraged to aid in radiotracer distribution and urinary clearance. Diabetic patients may require adjustments to insulin or medication schedules to maintain stable blood glucose levels.

On the day of the scan, a small amount of radioactive glucose (FDG) is injected intravenously. After the injection, the patient must rest quietly for 45–60 minutes to allow for adequate tracer uptake. It is important to avoid physical activity during this period, as muscle contractions can result in false signals.

During the scan itself, the patient lies on a movable table that slides through a circular PET/CT machine. The procedure is non-invasive and painless, typically lasting 20–30 minutes. Afterward, patients are encouraged to hydrate to help flush the remaining tracer from the body. In rare cases, mild allergic reactions or discomfort at the injection site may occur, but overall PET imaging is considered very safe.

PET Imaging for Surveillance After Colon Cancer Treatment

Monitoring Recurrence and Guiding Further Therapy

After initial treatment for colon cancer—whether surgical, chemotherapeutic, or radiologic—surveillance becomes a crucial phase of patient care. PET scans are especially valuable in the detection of recurrence, particularly in patients who present with elevated tumor markers like CEA but have negative findings on CT or colonoscopy. This functional imaging approach enables detection of metabolically active residual or recurrent disease.

Furthermore, PET is used to assess the effectiveness of ongoing therapy. Changes in FDG uptake over time can indicate whether tumors are responding to treatment, stabilizing, or progressing. This is especially relevant in cases involving complex metastases, where anatomical changes may lag behind metabolic changes.

The use of PET in post-treatment settings requires clinical judgment. Not every patient benefits from routine PET imaging, and it is typically reserved for high-risk cases or those with ambiguous symptoms. This approach parallels surveillance strategies in other cancers, including immune-resistant models discussed in lewis lung cancer and T cell exhaustion, where recurrence may present subtly.

The Use of PET in Staging Colon Cancer

How PET Helps Define Disease Progression

Staging is a critical component in managing colon cancer because it determines treatment direction and prognosis. PET imaging contributes significantly to Stage III and IV assessments by detecting distant metastases not visible on conventional imaging. For example, liver lesions may appear equivocal on CT but demonstrate clear FDG uptake on PET, confirming metastatic disease.

While PET is not part of the initial TNM classification system, its findings can lead to upstaging in many cases—identifying more extensive disease than previously known. This allows oncologists to modify treatment regimens appropriately, whether that means adding systemic therapy, altering surgical plans, or incorporating radiation. In situations where colon cancer metastasizes to unexpected sites, such as bone or adrenal glands, PET has demonstrated superiority over other imaging modalities in identifying hidden disease.

Furthermore, when staging cancer in female patients, clinicians must be cautious about physiological uptake in reproductive organs, which may mimic metastases. This nuance reinforces the importance of experience in reading PET images, as mistakes can significantly affect the management plan.

Differentiating Between Scar Tissue and Active Cancer

How PET Aids in Post-Surgical Assessment

After surgery or radiation therapy, distinguishing residual cancer from scar tissue is a well-known challenge. Both can appear as masses on CT or MRI, but only active tumors will show elevated glucose metabolism. PET scans are particularly valuable in this context because they can detect viable tumor cells within fibrotic or necrotic tissue beds.

This distinction helps avoid unnecessary repeat surgeries or biopsies and allows for more accurate surveillance. In cases where a previously treated area begins to grow, PET can determine if it’s a recurrence or benign post-treatment remodeling. This differentiation is vital in high-risk patients and those being considered for re-operation or salvage therapy.

Even in scenarios where anatomical imaging is inconclusive, a clear lack of FDG uptake on PET can provide peace of mind to both clinicians and patients. This is especially meaningful when managing elderly patients or those with comorbidities, where invasive follow-up procedures carry greater risks.

Interpreting PET Scan Results: What the Numbers Mean

SUV Values, Patterns, and Diagnostic Confidence

A key component of interpreting PET scans is understanding the Standardized Uptake Value (SUV), which quantifies the amount of FDG uptake in a region of interest. Higher SUVs often correlate with malignancy, though there is no absolute cutoff—what matters is relative activity compared to surrounding tissue and expected physiologic norms.

PET reports may highlight regions with focal intense uptake, which usually warrant further evaluation. Diffuse or mild uptake may be benign, especially in areas like the bowel or bladder. It is the radiologist’s role to interpret the patterns of uptake in the clinical context, factoring in prior history, recent treatments, and concurrent lab results.

For instance, an SUV of 2.5 might be suspicious in a lung nodule, while it could be less significant in a colon fold or inflamed diverticulum. This underscores the need for multidisciplinary review, where radiologists, oncologists, and surgeons collaborate to make decisions based on PET findings.

PET/CT Use Across Colon Cancer Stages

| Colon Cancer Stage | PET/CT Role | Primary Benefits | Common Findings |

| Stage I | Rarely used | Not indicated | Minimal uptake |

| Stage II | Occasionally | Clarifies lymph node involvement | Low FDG activity if low-grade tumor |

| Stage III | Often used | Detects regional spread, pre-op planning | Lymph node involvement, potential liver lesions |

| Stage IV | Routinely used | Identifies distant metastases, guides systemic therapy | Liver, lung, or bone metastases with high SUV |

This table summarizes when PET/CT becomes relevant across various stages of colon cancer. As shown, its utility increases with disease complexity, particularly in advanced stages. In earlier phases, anatomical imaging and biopsy remain the primary tools.

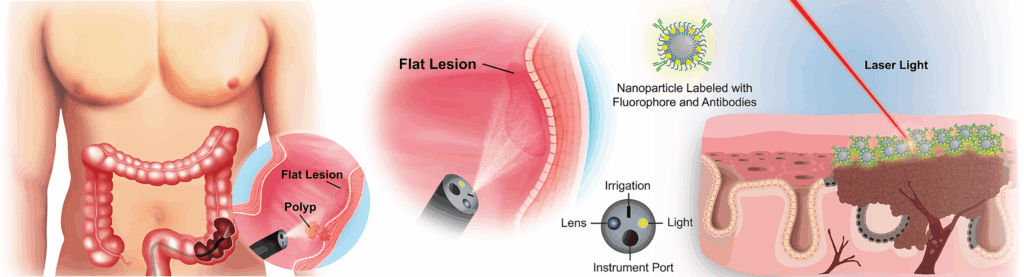

PET Versus Colonoscopy: Different Tools for Different Questions

Why PET Cannot Replace Direct Visualization

Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for initial diagnosis and direct visualization of the colon lining. It allows for biopsy and polyp removal in real time, capabilities that PET scans cannot provide. While PET is a powerful tool for functional imaging and detecting systemic disease, it does not visualize the mucosal surface, making it incapable of identifying flat lesions or subtle mucosal changes.

In clinical practice, PET and colonoscopy serve complementary roles. Colonoscopy is ideal for identifying and diagnosing primary tumors, while PET is employed for staging, recurrence detection, and identifying distant spread. In cases of suspected synchronous lesions—tumors occurring simultaneously in different parts of the colon—both tests may be used in combination.

It is also important to note that colonoscopy may miss extraluminal or metastatic disease entirely, reinforcing the added value of whole-body imaging through PET/CT. This interplay is especially important in complex diagnostic pathways and mirrors the approach taken in early-stage detection practices in skin-related tumors such as those seen in early stage eyelid cancer pictures.

PET’s Role in Guiding Surgical and Treatment Decisions

Helping Oncologists Plan More Precisely

The integration of PET scan data into surgical and therapeutic decision-making allows for more individualized treatment plans. PET helps surgeons determine resectability—whether a tumor or metastasis can be safely removed—and whether additional lesions are present that would alter the surgical approach. This is particularly useful in cases with liver metastases, where PET can help avoid unnecessary laparotomies.

On the oncologic side, PET scans support decisions regarding chemotherapy or radiation by identifying which areas of disease are active, potentially altering the scope or intensity of treatment. For example, a PET scan that shows regression in most areas but new uptake in another region may prompt a targeted treatment approach or localized radiation.

This targeted precision echoes evolving strategies in veterinary oncology, such as those used in alternative cancer treatments for dogs, where a combination of diagnostics and tailored therapies defines the modern standard of care.

Cost, Insurance, and Access Considerations for PET Imaging

Is PET Scanning Always Covered?

The cost of a PET scan can be substantial, often ranging from $3,000 to $6,000 depending on geographic location and healthcare system. Most insurance providers, including Medicare and Medicaid, cover PET scans when they are medically necessary—typically in the setting of confirmed or suspected malignancy, treatment planning, or recurrence monitoring.

However, coverage may require prior authorization and documentation of medical necessity. It is important for patients and providers to communicate clearly with insurance companies ahead of time to avoid unexpected expenses. In cases where insurance is not available, some institutions offer cash-pay discounts or assistance programs, though access may still be limited by equipment availability or geographic proximity to PET-capable facilities.

This economic barrier often influences diagnostic strategy, especially when other imaging modalities (such as CT or MRI) may provide enough information for basic staging, even if they lack the sensitivity of PET for metabolically active disease.

Future Directions in PET Imaging for Colon Cancer

Emerging Tracers, AI Integration, and Personalized Oncology

As technology continues to evolve, the future of PET imaging in colon cancer care looks increasingly promising. New radiotracers beyond FDG are under development to target specific tumor receptors or metabolic pathways, improving detection in tumors that are traditionally less metabolically active. For example, tracers targeting amino acid metabolism or hypoxia are already in early clinical use.

Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) is streamlining scan interpretation by automating lesion detection and quantification. AI algorithms can rapidly flag suspicious areas and compare images across time points with greater consistency, reducing human error and speeding diagnosis.

Moreover, the role of PET in personalized medicine is expanding. By correlating imaging data with molecular profiling, clinicians may soon be able to predict which patients are more likely to benefit from certain treatments or develop resistance. These advancements will further refine the already sophisticated use of PET in colon cancer care, mirroring how precision models are being evaluated in immuno-oncology research, such as in lewis lung cancer and T cell exhaustion.

FAQ

Can a PET scan detect colon cancer at an early stage?

PET scans are generally not the first choice for early-stage colon cancer detection. While they can identify metabolically active tissue, many early colon cancers have low metabolic activity and may not show up clearly on PET. Colonoscopy remains the more sensitive tool for identifying small or flat lesions in early stages. However, if there is suspicion of systemic spread or unclear findings on other scans, PET may be utilized to assess further.

Is a PET scan more accurate than a CT scan for colon cancer?

Both PET and CT scans have different strengths. CT provides excellent anatomical detail, while PET highlights metabolic activity. When combined as PET/CT, they offer a powerful diagnostic tool. PET can identify active disease even when a CT appears normal, especially in lymph nodes or distant organs. However, CT remains better for detailed anatomical boundaries and surgical planning.

Can PET scans help determine if colon cancer has spread?

Yes, this is one of the primary reasons PET scans are used in colon cancer management. They are particularly effective in identifying distant metastases to the liver, lungs, bones, or adrenal glands. By highlighting areas of increased metabolic activity, PET can guide staging and determine the extent of systemic disease more accurately than many other imaging tools.

How long does a PET scan for colon cancer take?

The entire PET scan process typically takes between 2 to 3 hours. Patients first receive an injection of the radiotracer and then rest quietly for about an hour to allow for distribution. The actual scanning process takes 20–45 minutes. The time may vary slightly depending on whether a PET/CT hybrid system is used and the number of body areas being scanned.

Do you need to fast before a PET scan?

Yes, patients are usually required to fast for at least 4 to 6 hours before a PET scan. This helps reduce background glucose levels, improving the accuracy of the FDG tracer uptake and resulting in clearer images. Water is typically allowed, but high-sugar foods or drinks can interfere with results and should be avoided.

Are there risks associated with PET scans?

PET scans are generally considered safe. The amount of radioactive tracer used is small and typically does not pose significant risk. The most common side effects are minor and include injection site irritation or allergic reaction to the tracer. Unlike contrast-enhanced CT scans, PET rarely uses iodine, which can be beneficial for patients with kidney issues.

Can inflammation or infection mimic cancer on a PET scan?

Yes, one of the limitations of PET imaging is that inflammation and infection also cause increased glucose metabolism, which can result in false-positive findings. This is why PET results are always interpreted in conjunction with clinical history, lab data, and other imaging. An experienced radiologist can often differentiate based on pattern and intensity of uptake.

Does a negative PET scan mean I don’t have colon cancer?

Not necessarily. A negative PET scan might simply mean that there is no metabolically active disease detectable at the time of the scan. Some tumors may be too small or biologically inactive to show up. If colon cancer is still suspected due to symptoms or other tests, further investigations like colonoscopy or biopsy are warranted.

Can PET scans detect colon cancer recurrence?

Yes, PET scans are frequently used to detect recurrence, particularly in patients who have undergone surgery or chemotherapy. They are valuable when tumor markers like CEA rise or when there are vague symptoms but no clear findings on CT. PET can detect early relapse before anatomical changes become visible.

Is PET scan useful after colon cancer surgery?

After surgery, PET scans can help monitor for recurrence or detect residual disease. They are particularly helpful in differentiating between scar tissue and viable tumor cells. This distinction is critical when considering additional treatment options or when symptoms reappear after a disease-free interval.

How does PET scan guide treatment for colon cancer?

PET scan findings influence treatment planning by confirming whether the cancer has spread, how active it is, and whether certain areas need targeted therapy. If new metastases are found, systemic therapy may be initiated or adjusted. In some cases, localized radiation or surgical resection can be planned based on PET findings.

Will my insurance cover a PET scan for colon cancer?

Most insurance providers, including Medicare, will cover PET scans if they are deemed medically necessary. This typically includes scenarios such as staging newly diagnosed cancer, evaluating treatment response, or detecting recurrence. However, pre-authorization is often required, and coverage may vary depending on the provider and healthcare setting.

Can PET scans replace biopsies in colon cancer diagnosis?

No, PET scans cannot replace biopsies. While PET can suggest the presence of cancer based on metabolic activity, it cannot definitively diagnose malignancy. Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis and is necessary for identifying tumor type, grade, and molecular features.

Are PET scans used during chemotherapy treatment?

Yes, PET scans can be used to evaluate treatment response during or after chemotherapy. A decrease in FDG uptake typically indicates that the tumor is responding to therapy. However, timing is important—scans done too early may not accurately reflect changes, as inflammation from treatment can temporarily increase uptake.

How do I prepare for a PET scan if I have diabetes?

Diabetic patients need careful planning before a PET scan. Blood glucose should be well-controlled prior to the procedure, ideally below 200 mg/dL. High glucose levels can interfere with FDG uptake and affect image quality. Insulin timing and diet adjustments may be necessary, and should be coordinated with the imaging team.