Common Reasons for Side Pain and How It’s Managed

Anatomy and Clinical Nature of Side Pain

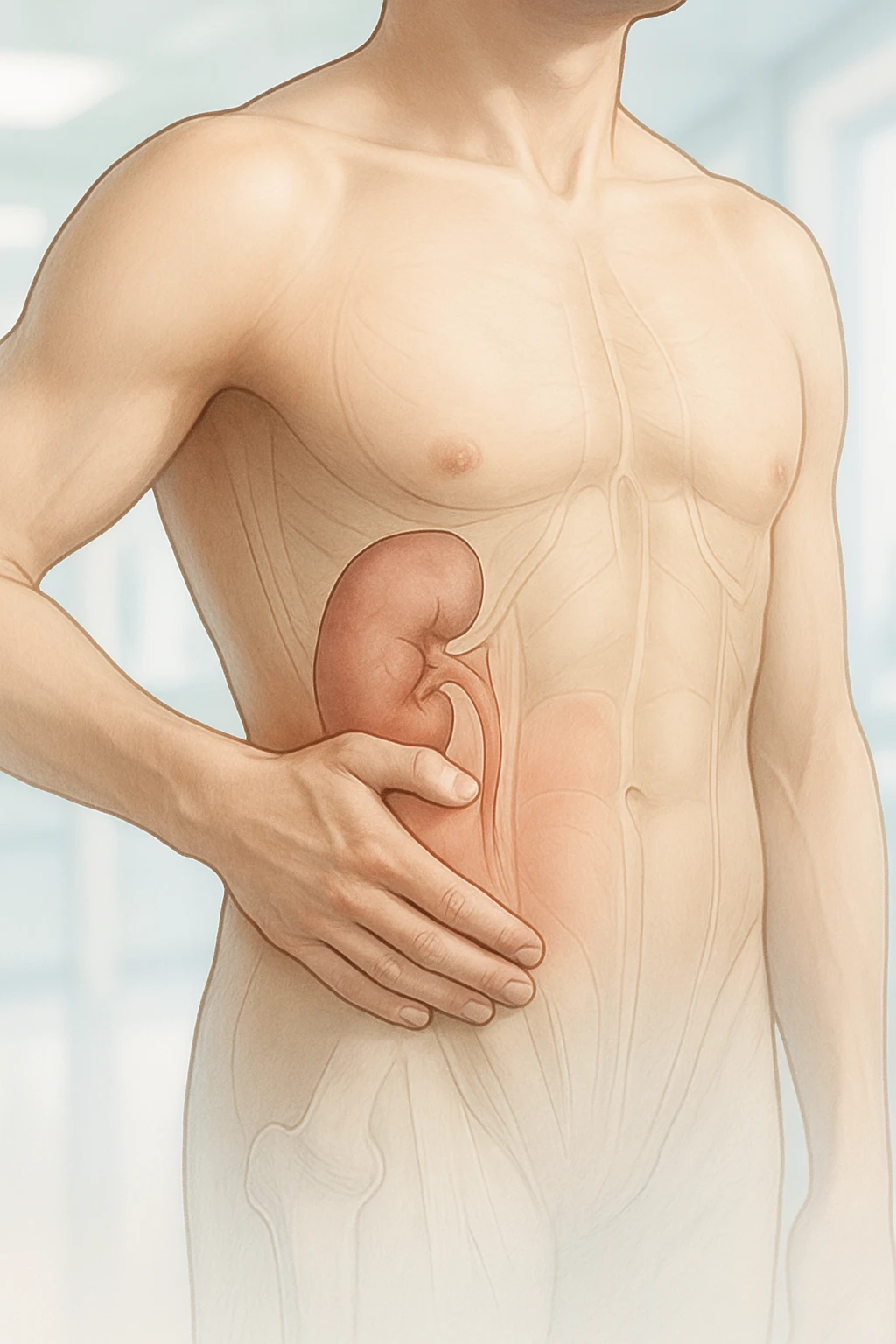

Side pain, often referred to clinically as flank pain, describes discomfort felt on one side of the body between the upper abdomen and the back. This region encompasses structures of the abdominal wall, retroperitoneal organs, and lower ribs. Because multiple organ systems and musculoskeletal components converge in this area, side pain can arise from diverse mechanisms such as renal irritation, pleural inflammation, muscular strain, or nerve entrapment. Accurate localization and characterization are essential for determining its origin and clinical relevance.

Defining Side and Flank Pain

Flank pain occurs on either side of the torso, bordered superiorly by the ribs and inferiorly by the iliac crest. It often overlaps anatomically with the lateral abdominal wall and posterior thoracoabdominal region. Pain in this zone may originate from deeper visceral structures such as the kidneys or retroperitoneal organs, or from more superficial musculoskeletal components.

- Deep sources: kidneys, retroperitoneal organs

- Superficial sources: abdominal wall muscles, fascia, and skin

Identifying whether the pain is superficial or deep helps clinicians differentiate abdominal wall involvement from intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal sources.

Differentiating Side Stitch (ETAP) from Chronic Side Pain

Exercise-related transient abdominal pain, commonly called a side stitch or ETAP, is a benign, short-lived discomfort along the lateral abdomen during physical activity. Unlike persistent flank pain, ETAP resolves quickly with rest and does not signify underlying disease. The pain is typically sharp or cramping and results from repetitive torso movement or diaphragmatic strain.

| Feature | ETAP (Side Stitch) | Chronic Side Pain |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | During exercise | Often persistent or recurrent |

| Duration | Short-lived; resolves with rest | Prolonged; may need evaluation |

| Nature | Sharp or cramping | Structural, inflammatory, or neuropathic |

Chronic or recurrent side pain often reflects structural, inflammatory, or neuropathic processes that require further clinical assessment.

Referred Pain Patterns

Due to complex thoracic and abdominal wall innervation, side pain may originate from remote structures. Musculoskeletal and spinal disorders can radiate laterally via shared nerve pathways, while rib or pleural irritation may produce localized tenderness mimicking renal or abdominal wall pain.

- Spinal disorders: Lateral radiation via thoracic nerves

- Pleural or rib irritation: Local tenderness along the costal margin

- Nerve entrapment or wall strain: Focal tenderness confined to a small area

Recognizing these patterns helps differentiate referred pain from visceral discomfort.

Clinical Causes and Mechanisms of Side Pain

Side pain arises from several systems, including renal and urinary tract, musculoskeletal, abdominal wall, and exercise-related factors. Recognizing the characteristic features of each helps guide accurate diagnosis and management.

Renal and Urinary Tract Causes

The kidneys and ureters commonly produce acute unilateral flank pain. Ureteral stones cause severe, colicky pain radiating toward the groin due to obstruction and distension of the urinary tract. When flank pain occurs with fever or systemic symptoms, pyelonephritis or infected obstruction should be suspected. Distinguishing between obstructive and infectious causes is critical, as management urgency differs.

- Obstructive causes: Ureteral stones causing acute afebrile flank pain.

- Infectious causes: Pyelonephritis or infected obstruction with fever or systemic signs.

- Clinical importance: Differentiation guides treatment urgency.

Musculoskeletal and Abdominal Wall Pain

Musculoskeletal strain or localized nerve entrapment in the abdominal wall are frequent nonrenal causes of side pain. Repetitive motion, poor posture, or overuse of trunk muscles can provoke myofascial irritation that worsens with movement or palpation. Anterior cutaneous nerve entrapment typically presents as a small, focal tender point that becomes more painful during abdominal contraction, distinguishing it from visceral pain, which worsens with deep palpation.

- Musculoskeletal strain: Pain aggravated by movement or posture.

- Nerve entrapment: Localized tenderness increasing with muscle contraction.

- Diagnostic clue: Pain localization differentiates wall from visceral origin.

Exercise-Related Pain Mechanisms

Exercise-related transient abdominal pain (ETAP) is benign and self-limited, presenting as sharp or cramping discomfort along the lateral abdomen during activity. It is highly prevalent among endurance athletes and resolves with rest. Repetitive torso motion and diaphragmatic strain are suspected triggers.

| Feature | ETAP (Exercise Pain) | Other Causes |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | During exercise | Unrelated to activity |

| Duration | Short-lived | Persistent or recurrent |

| Clinical significance | Benign; no systemic illness | May reflect structural or infectious origin |

Recognizing ETAP helps differentiate benign exercise-related pain from pathological causes requiring medical attention.

Recognizing Clinical Patterns and Red Flags in Side Pain

Evaluation of side pain depends on understanding pain characteristics, systemic symptoms, and warning signs indicating potential serious disease. Pain quality, radiation, and associated findings narrow the diagnostic focus and guide clinical urgency.

Pain Quality and Distribution

Renal colic is typically severe, colicky pain that fluctuates as the ureter contracts against obstruction, often radiating from the flank to the groin and accompanied by hematuria. In contrast, ETAP is sharp or cramping, triggered by activity, and resolves with rest. Differentiating these patterns assists in distinguishing visceral obstruction from benign, exercise-related discomfort.

| Feature | Renal Colic | Exercise-Related Pain (ETAP) |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Quality | Colicky, severe | Sharp or cramping |

| Radiation | Flank to groin | Costal margin or lateral abdomen |

| Resolution | After relief of obstruction | Quickly with rest |

Associated Systemic Symptoms

Systemic findings often signal infection or inflammation of the renal or urinary tract. Fever, chills, malaise, or nausea with flank pain indicate infection such as pyelonephritis, whereas severe pain without systemic signs suggests obstruction. Hematuria may occur in both cases. Correlating pain features with systemic findings refines diagnostic accuracy.

- Infectious indicators: Fever, chills, malaise, nausea.

- Noninfectious indicators: Severe pain without systemic features.

- Common overlap: Hematuria in both obstructive and inflammatory states.

Red Flags and When to Seek Care

Red flags in side pain evaluation include flank pain with fever, chills, or hematuria, which may signify serious renal pathology. Persistent or severe pain, especially with systemic symptoms like nausea or fatigue, warrants prompt medical evaluation.

- Fever, chills, or hematuria with side pain

- Severe or persistent pain unrelieved by rest

- Systemic symptoms: nausea, fatigue, malaise

Diagnostic Evaluation and Work-Up for Side Pain

Accurate diagnosis of side pain requires structured assessment combining history, examination, and targeted testing. The objective is to determine origin-renal, musculoskeletal, or abdominal wall-and identify urgent findings.

Clinical History and Examination

History should address onset, duration, radiation, and aggravating or relieving factors. Triggers like movement or urinary symptoms may reveal etiology. Pain radiating to the groin suggests ureteral obstruction, while posture-related pain indicates musculoskeletal causes.

- Onset and pattern: Sudden pain suggests obstruction; gradual onset implies strain or inflammation.

- Radiation: Groin involvement indicates ureteral pain; localized tenderness indicates wall origin.

- Triggers: Movement or contraction implies musculoskeletal source.

- Associated symptoms: Fever, nausea, hematuria guide renal or infectious suspicion.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory and imaging studies confirm or exclude renal and nonrenal causes. Urinalysis detects infection or hematuria, renal tests assess function, and imaging-ultrasound or CT-clarifies structure and obstruction.

| Test | Purpose | Common Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Urinalysis | Detect infection or hematuria | Blood or leukocytes |

| Renal function tests | Assess kidney performance | Elevated creatinine |

| Ultrasound | Initial imaging for stones | Hydronephrosis or calculi |

| CT scan | Detailed anatomic evaluation | Stone localization or masses |

Flank pain with fever or hematuria warrants urgent investigation to rule out infection or obstruction.

Applying the Carnett Test

The Carnett test differentiates abdominal wall pain from intra-abdominal pathology. The patient tenses the abdominal muscles while pressure is applied over the tender area. Pain that persists or increases supports an abdominal wall origin, while decreased pain suggests visceral origin.

- Positive test: Persistent pain – abdominal wall origin.

- Negative test: Reduced pain – visceral source.

When to see a doctor: Fever, chills, hematuria, or persistent pain not improving with rest should prompt medical evaluation, as these may indicate infection or urinary obstruction requiring timely treatment.

Management, Prevention, and Prognosis of Side Pain

Effective management of side pain depends on identifying its underlying cause and relieving symptoms while addressing the primary pathology. A structured approach helps differentiate renal, musculoskeletal, and abdominal wall origins, allowing for precise therapeutic targeting. Preventive strategies and understanding prognosis are equally important to reduce recurrence and ensure optimal outcomes.

Treatment by Etiology

Treatment strategies for side pain are specific to the cause. For renal or urinary tract conditions such as infection or obstruction, management targets the primary process: antibiotics for infection and hydration with analgesia for stones to aid passage. When infection and obstruction coexist, urgent medical care is necessary to prevent complications.

- Renal or urinary causes: Antibiotics for infection; hydration and analgesia for stones.

- Musculoskeletal causes: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy for strain or postural imbalance.

- Abdominal wall pain: Local anesthetic injection with or without corticosteroid; surgical neurectomy for refractory cases.

These targeted interventions highlight the importance of accurately determining the source of pain before initiating treatment.

Preventive and Lifestyle Measures

Prevention of recurrent side pain involves addressing modifiable risk factors associated with each etiology.

- Renal colic: Maintain hydration and moderate intake of stone-forming minerals.

- Musculoskeletal pain: Improve ergonomics and incorporate regular core-strengthening exercises.

- Exercise-related transient abdominal pain (ETAP): Avoid large meals or hypertonic drinks before activity; apply proper breathing and posture techniques during exercise.

Educating patients about these preventive measures helps support long-term symptom control and reduces recurrence of side pain.

Prognosis and Follow-Up

The prognosis for most causes of side pain is favorable when appropriately managed. Renal stones and infections often resolve with medical therapy, though recurrence can occur without preventive strategies. Musculoskeletal and abdominal wall pain typically improve with targeted treatment and rehabilitation, while persistent cases may benefit from multidisciplinary evaluation. ETAP is benign and self-limited, resolving with behavioral adjustments.

| Condition | Typical Outcome | Key Follow-Up Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Renal stones or infection | Usually resolves with medical therapy | Monitor hydration and recurrence risk |

| Musculoskeletal pain | Improves with therapy and exercise | Reassess posture and ergonomic habits |

| Abdominal wall pain (nerve entrapment) | High short-term relief with injection | Consider surgical neurectomy if persistent |

| ETAP | Benign and self-limited | Review exercise habits and hydration |

For specific populations such as older adults, athletes, and individuals with comorbidities, management should be individualized. Older adults may require medication adjustments or modified imaging approaches, while athletes benefit from conditioning and hydration-focused strategies. Across all groups, prompt recognition of red flags-including fever, hematuria, or persistent severe side pain-remains critical for safe and effective care.

Frequently Asked Questions About Side Pain

- Where exactly is side pain felt?

- Side pain, or flank pain, is usually felt on one side between the upper abdomen and the back. It may extend toward the lower ribs or groin depending on the cause.

- What are the most common causes of side pain?

- Common causes include kidney stones, urinary infections, muscle strain, and abdominal wall nerve irritation. Less often, side pain can result from pleural or spinal conditions.

- How can I tell if side pain is from the kidneys?

- Kidney-related pain often feels deep, severe, and may radiate toward the groin. When accompanied by fever, chills, or blood in the urine, it may indicate infection or obstruction.

- Can muscle or nerve problems cause pain along the side?

- Yes. Musculoskeletal strain and abdominal wall nerve entrapment can cause localized tenderness that worsens with movement or muscle contraction rather than deep pressure.

- What is a side stitch during exercise?

- A side stitch, or exercise-related transient abdominal pain (ETAP), is a brief, sharp, or cramping pain along the side that appears during physical activity and subsides with rest.

- When should I seek medical care for side pain?

- Seek prompt evaluation if pain is severe, persistent, or associated with fever, nausea, vomiting, or blood in the urine, as these may signal serious kidney or urinary conditions.

- How do doctors diagnose the cause of side pain?

- Diagnosis involves a medical history, physical examination, and targeted testing such as urinalysis or imaging with ultrasound or CT to identify infection, stones, or muscle involvement.

- What is the Carnett test and why is it used?

- The Carnett test helps distinguish abdominal wall pain from deeper organ causes. If pain increases when the abdominal muscles tighten, it suggests a wall or nerve origin.

- Can side pain be prevented?

- Some causes can be reduced by staying hydrated, maintaining good posture, avoiding overexertion, and using proper breathing and exercise techniques to prevent strain or ETAP.

- What is the outlook for people with side pain?

- Most cases resolve with appropriate treatment and lifestyle changes. Kidney stones or infections may recur, but musculoskeletal and exercise-related pain often improve fully with management.