Cat Mammary Cancer: Signs, Treatment, Prognosis & Euthanasia

Foreword

If you’re here, there’s a good chance you’ve found a lump on your cat—or your vet has—and you’re wondering, “How serious is this?” Or maybe you’ve already heard the word “cancer,” and your world has tilted, just a little. That’s completely normal. When it comes to our pets, especially cats who are famously private and stoic creatures, any sign of illness can feel like a betrayal of the unspoken bond we share with them. But knowledge is power, and the first step toward making the best decisions for your cat is understanding exactly what mammary cancer is—and isn’t.

Let’s walk through it together.

What Is Mammary Cancer in Cats?

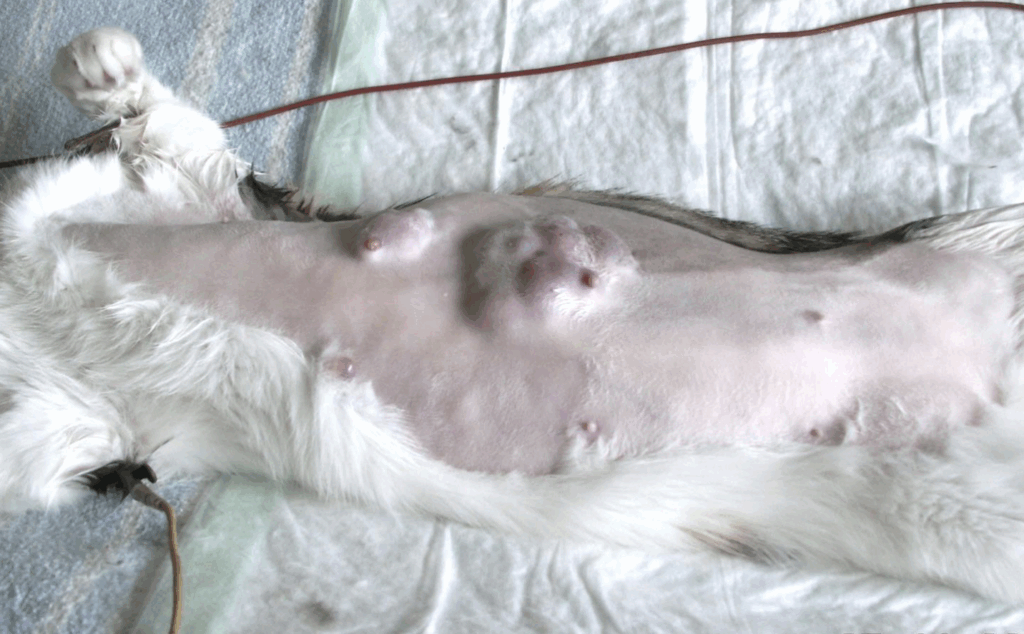

Feline mammary cancer is a malignant tumor—meaning it has the potential to invade Feline mammary cancer is a malignant tumor that originates in the mammary glands—eight in total, arranged in four pairs from the chest to the groin. These tumors can arise in any of the glands but tend to cluster most often in the caudal (rear) ones. Malignancy means the tumor has the capacity to invade surrounding tissue and metastasize to distant organs, making early detection and intervention crucial.

While not every mammary lump in a cat is malignant, the odds are sobering: approximately 85% to 90% of feline mammary tumors are cancerous. This malignancy rate is dramatically higher than what’s seen in dogs. As such, any lump detected in the mammary area warrants timely evaluation. Waiting in hopes that a mass will “go away on its own” often sacrifices valuable time in what is typically a fast-moving disease.

The risk of mammary cancer is closely linked to hormonal exposure. Estrogen and progesterone—central to the development of mammary tissue—also appear to play a role in oncogenic transformation. Spaying at an early age dramatically reduces this risk. Cats spayed before six months of age see a risk reduction of roughly 91%. When spaying is delayed until the cat is one year old, that protective effect drops to about 86%. After two years, the benefit in terms of cancer prevention becomes negligible.

This connection makes intact females the most vulnerable group, particularly as they age. The majority of diagnoses occur between the ages of 10 and 12. While spaying later in life may still offer other health advantages, its protective power against mammary cancer is almost entirely time-sensitive.

Though far less common, male cats can develop mammary tumors as well. They possess vestigial mammary tissue and, in rare cases, may experience malignancies that are often aggressive when they do occur. The rarity of such cases doesn’t diminish their clinical seriousness.

Breed appears to influence risk as well. Siamese cats, in particular, are overrepresented in mammary cancer statistics. They not only have a higher likelihood of developing these tumors but often do so at a younger age than other breeds. The precise reasons remain uncertain, but a heritable component is suspected.

There are also modifiable risk factors to consider. Obesity—especially in early life—has been suggested as a possible contributor, although data on this is mixed. The use of progestin-based hormone treatments, once more common in behavioral or reproductive management, is known to increase the risk of mammary tumors due to their estrogenic effects. While not a direct cause, chronic irritation or inflammation of mammary tissue is another concern; repeated cellular damage can, over time, predispose tissues to neoplastic transformation.

What makes feline mammary cancer particularly unforgiving is its speed and subtlety. Tumors often go unnoticed until they’ve reached an advanced size or have already metastasized. Cats, by nature, are discreet creatures. They don’t advertise discomfort. A tumor may be quietly growing under the fur, evading detection during casual handling, until it finally makes itself known by size, ulceration, or associated symptoms.

| Spay Timing | Estimated Risk Reduction | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Before 6 months | ~91% | Most effective window for cancer prevention |

| Before 1 year | ~86% | Still highly protective |

| After 2 years | Minimal | Offers little protection against mammary cancer |

| Not spayed | — | Highest lifetime risk |

Pathologically, these tumors tend to be high-grade and fast-growing. The majority are adenocarcinomas—cancers arising from glandular tissue—which are biologically aggressive and often infiltrative. Unlike dogs, who frequently develop benign mammary tumors, cats are rarely so lucky. Here, the rule is to assume malignancy until proven otherwise.

Feline mammary cancer is the third most common cancer in cats, trailing only skin tumors and lymphomas. Statistically, about one in 400 cats will develop a mammary tumor. Among unspayed females over ten, the incidence climbs steeply. While those numbers may sound abstract, the reality becomes deeply personal when it’s your cat—and the next steps are no longer theoretical.

And those next steps begin with recognizing what to look for, how the disease is diagnosed, and what treatment paths are available. Because the earlier you act, the more choices you have—and the better your cat’s chances will be.

If you’re wondering how this compares to human forms of breast cancer, there’s a compelling overview on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer — a subtype that’s also aggressive and difficult to treat.

Recognizing the Signs

Feline mammary cancer rarely announces itself with drama. There’s no grand warning, no obvious collapse. Instead, it tends to arrive quietly—tucked beneath fur and flesh, often hidden in the long space between vet visits. For many owners, the first sign is incidental. They’re petting their cat, or perhaps trimming her nails, when a small lump is discovered along the belly. It may feel firm or nodular, maybe the size of a pea, and often doesn’t seem to bother the cat at all.

That’s precisely what makes it so dangerous. In the early stages, these tumors are often painless and discreet. There’s no redness, no discharge, no obvious swelling to draw attention. And because cats are masters of masking discomfort, they rarely give us behavioral clues until the disease has already advanced.

When a lump is noticed, it’s typically located near one of the eight mammary glands. The rear glands—those closest to the groin—are the most common sites of tumor development. But any gland, on either side, can be affected. Sometimes multiple glands are involved, either simultaneously or progressively, forming what can look and feel like a chain of masses. This multifocal pattern is not unusual and is one of the reasons why targeted removal of a single lump is often insufficient. What presents as a localized issue may, in truth, be part of a broader infiltration along the mammary line.

As the tumor progresses, it may begin to alter the surrounding skin. Ulceration—where the overlying skin breaks down—can occur, leading to open wounds, bleeding, or infection. At this stage, the mass is often obvious to the eye as well as the hand. The fur may be matted or missing, the area tender. Some cats will begin licking or biting at the tumor site, a sign that discomfort has escalated.

Beyond the mass itself, changes in behavior may be subtle but telling. A cat who once lounged in sunbeams may now seek secluded spots. She may become less tolerant of touch, more hesitant to jump, or disinterested in food—not due to a finicky appetite, but due to underlying discomfort or systemic illness. Respiratory changes, such as heavier breathing or labored effort, may suggest that metastasis has reached the lungs, especially if fluid begins to accumulate in the pleural space. These changes, though easy to dismiss as aging or temperament, should always be taken seriously.

Not all of these signs point to cancer. Other conditions—mastitis, abscesses, benign growths—can present similarly. But in cats, the statistical probability leans heavily toward malignancy, and waiting to “see what happens” risks giving the disease a head start it doesn’t need. Size matters. Tumors under two centimeters in diameter have significantly better prognoses than those that exceed three. And once lymph nodes or lungs are involved, treatment becomes more complex and outcomes more guarded.

It’s also worth noting that cats with mammary cancer often carry more than just a tumor. They carry silence. They carry all the signals we’re not trained to see. Which is why monthly at-home physical exams are so valuable. A gentle palpation along the belly, from chest to groin, is often all it takes to spot a problem before it becomes an emergency.

Ultimately, the earlier the disease is detected, the more options are available—for surgery, for systemic therapy, and for preserving quality of life. The time to act is not when the tumor becomes unignorable, but when it’s still small, silent, and seemingly insignificant. In feline oncology, the difference between weeks and months can be life-changing.

Recognizing the signs means looking beyond what’s obvious. It means trusting your hands, your instincts, and your willingness to investigate a problem your cat may never fully reveal. And once the suspicion is there, diagnosis becomes the next critical step—a move from uncertainty into clarity, where the real decisions begin.

Diagnostic Procedures

Once a mammary lump has been discovered, the next step is no longer speculation—it’s confirmation. This is the pivot point where suspicion becomes structure, where worry becomes action. Because even if the lump seems small or your cat seems “fine,” the biology of feline mammary cancer doesn’t wait for dramatic symptoms. The clock starts ticking well before the disease becomes visibly disruptive.

The diagnostic process is designed to answer three fundamental questions:

- What is it? (Is the mass malignant, and if so, what type?)

- Where is it? (Is the tumor confined, or has it spread?)

- How bad is it? (What is the biological behavior and potential trajectory?)

These answers don’t just satisfy curiosity—they shape everything that follows, from surgery planning to prognosis.

The Physical Exam: The Art of Skilled Hands

Diagnosis begins in the exam room, where your veterinarian will conduct a thorough physical assessment. This is more than a quick once-over. Each mammary gland will be palpated individually, checking for nodules, heat, ulceration, or firmness. Often, what feels like a single mass may actually be part of a linear chain—evidence of multifocal spread.

The vet will also evaluate:

- Regional lymph nodes, particularly the axillary (armpit) and inguinal (groin) nodes, for swelling or abnormal firmness—signs of possible metastatic involvement.

- Respiratory patterns, noting any signs of labored breathing that might indicate metastasis to the lungs or pleural effusion.

- Overall condition, assessing hydration, muscle tone, and energy to determine the cat’s baseline resilience and suitability for future interventions.

This hands-on exam sets the stage, but it can’t provide the whole picture. That’s where imaging and sampling come in.

Imaging: Seeing Beyond the Surface

Because feline mammary cancer spreads most commonly to the lungs, lymph nodes, and sometimes the liver or chest cavity, internal imaging is critical to staging. It helps determine whether the disease is still localized or has already crossed into systemic territory.

Common imaging tools include:

- Thoracic radiographs (chest X-rays)

These are standard and non-invasive. A three-view series—left lateral, right lateral, and ventrodorsal—is ideal to visualize the lungs fully and avoid missing small metastases. The goal is to identify nodules, fluid buildup, or masses that suggest metastatic disease. - Abdominal ultrasound

Especially valuable when evaluating deeper lymph nodes, the liver, or other abdominal organs. It can reveal subtle changes invisible on palpation or X-ray, and help rule in or out concurrent conditions. - Mammary chain ultrasound

Some advanced practices use detailed sonography to evaluate the extent of local disease—checking the depth, vascularity, and margins of tumors to aid in surgical planning. - CT scans

Less common, but sometimes employed in referral settings for high-detail mapping, especially before complex or repeat surgeries. CT can offer a more precise look at both lung fields and tissue infiltration when standard imaging is inconclusive.

Each of these tools adds a layer to the diagnostic mosaic. Together, they help paint a realistic picture of what you and your cat are truly dealing with.

Sampling the Tumor: FNA vs. Biopsy

The next major step involves obtaining a sample of the tumor—either via needle or scalpel—for definitive analysis. This is where the process can get a bit more nuanced.

Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) is often the first approach. It involves inserting a thin needle into the lump to extract a small number of cells for cytological examination. It’s fast, minimally invasive, and often done during the same appointment.

| Diagnostic Tool | Purpose | Usage Context |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Exam | Palpation of mammary chain and lymph nodes | Initial clinical assessment |

| Thoracic Radiographs (X-ray) | Detect lung metastasis or pleural effusion | Pre-surgical staging; suspected spread |

| Abdominal Ultrasound | Evaluate internal organs and lymph nodes | Assess metastasis; check for concurrent issues |

| Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) | Extract cells from lump for cytology | Quick but often inconclusive in cats |

| Biopsy + Histopathology | Determine tumor type, grade, and margin status | Gold standard for diagnosis |

But here’s the catch: FNA has limitations in feline mammary tumors. These tumors tend to be fibrous, low-yield, and cytologically ambiguous. Even aggressive tumors can look deceptively benign under a microscope if the sample is sparse or poorly exfoliated.

In contrast, biopsy with histopathology is considered the gold standard. This involves removing part (incisional) or all (excisional) of the tumor tissue for detailed laboratory analysis. Histopathology doesn’t just look at individual cells—it examines the tissue architecture, cellular behavior, mitotic activity, and invasion pattern. From this, a tumor type, grade, and prognosis can be established.

Histopathology answers critical questions:

- Is the tumor an adenocarcinoma?

- Is it low-, intermediate-, or high-grade?

- Were the surgical margins clean?

- Are there signs of lymphovascular invasion?

These findings are essential for both treatment planning and realistic discussions about outcomes.

Lymph Node Evaluation: The Understated Essential

Too often overlooked, regional lymph node assessment is a cornerstone of accurate staging. Even when lymph nodes appear normal externally, they can harbor microscopic metastases that drastically change prognosis.

Whenever feasible, aspiration or biopsy of the draining lymph nodes should be performed, particularly if the node is enlarged or the tumor is high-grade. In some cases, removal of the node during surgery allows for complete histological analysis and ensures more accurate staging.

Skipping lymph node assessment is a common source of under-treatment—or under-preparation. What may appear to be a localized cancer could, in fact, already be regionally advanced.

Bloodwork: Supporting Cast, Not Lead Role

Routine blood tests—such as a complete blood count (CBC) and serum biochemistry panel—won’t confirm or rule out cancer. But they do help assess your cat’s readiness for surgery or chemotherapy. They also detect any underlying issues that could complicate anesthesia or post-op recovery.

Key parameters include:

- Liver and kidney values

- Electrolyte balance

- Red and white blood cell counts

- Glucose and albumin levels

If your cat is a senior, a thyroid panel (usually T4) may also be recommended, since hyperthyroidism is common in aging cats and can influence treatment decisions.

Staging and Prognosis

By now, you’ve likely had the diagnostics done—or you’re preparing to—and you want to know what it all means. You’re not just looking for raw data; you’re trying to understand the story the cancer is telling, and more importantly, where in that story your cat currently stands.

| Factor | Favorable Prognosis | Unfavorable Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor Size | < 2 cm | > 3 cm |

| Lymph Node Involvement | None | Positive node(s) |

| Surgical Margins | Clean | Incomplete |

| Tumor Grade | Low or Intermediate | High-grade or anaplastic |

| Presence of Metastasis | None (localized disease) | Lungs, liver, or distant spread |

| Treatment Type | Full mastectomy ± chemo | No surgery or palliative only |

This is where staging comes in. Staging is the framework vets and oncologists use to determine how far the cancer has progressed and, by extension, how it’s likely to behave going forward. And yes, it matters. A lot. The treatment plan, the likelihood of recurrence, the chances of metastasis, and the prognosis all hinge on accurate staging.

But before we dig in, here’s something important: staging isn’t about fear. It’s about clarity. It’s how we move from “What are we facing?” to “What can we do?”

How Staging Works in Feline Mammary Cancer

Veterinarians often use a system adapted from human oncology called TNM staging:

- T (Tumor): The size of the primary tumor and whether it’s fixed to surrounding tissue.

- N (Node): Whether nearby lymph nodes are involved.

- M (Metastasis): Whether the cancer has spread to distant organs like the lungs, liver, or elsewhere.

It’s deceptively simple in structure but incredibly powerful in practice.

Let’s break it down:

Tumor (T)

Tumor size is not just a number on paper—it’s one of the most predictive factors in feline mammary cancer.

- Tumors less than 2 cm tend to carry a far better prognosis.

- Tumors between 2–3 cm are more concerning.

- Tumors greater than 3 cm have significantly worse outcomes, especially if they’re ulcerated or infiltrating adjacent tissue.

Size correlates strongly with both metastatic risk and biological aggressiveness. Small tumors, when caught early and removed cleanly, can result in long disease-free intervals—even cures. Larger ones, especially those that have adhered to the skin or muscle, are more likely to have already begun their journey elsewhere.

Node (N)

Lymph node involvement is a game-changer. The two primary nodes examined in feline mammary cancer are the axillary (armpit) and inguinal (groin) lymph nodes. If the tumor drains into a nearby node, and that node tests positive for cancer, the disease is considered regionally advanced.

Even if the tumor is small, a positive lymph node ups the risk of systemic spread. This is why many oncologic surgeons strongly recommend removing and biopsying associated lymph nodes during surgery. It’s not just about clearing tissue—it’s about knowing what you’re up against.

And yes, it’s entirely possible for lymph nodes to feel normal on palpation and still harbor micrometastases. Which brings us back to the value of histopathology and thorough surgical planning.

Metastasis (M)

This is the elephant in the room. If cancer has already spread to distant organs—most often the lungs, followed by the liver or pleural space—then the disease is considered stage IV, and the prognosis shifts dramatically.

That said, it’s worth remembering that radiographic metastases aren’t always present, even in aggressive tumors. Some cats live many months, even years, with no visible signs of systemic spread. The absence of metastasis on imaging is a good sign—but not a guarantee. This is why post-surgical monitoring remains vital even in “clean” cases.

How Staging Influences Prognosis

So what does all this mean for your cat’s outlook?

Here’s the broad truth: feline mammary cancer is serious. It’s not one of the “low-impact” cancers we sometimes see in veterinary medicine. But prognosis varies widely based on the factors we’ve just covered.

Favorable Prognostic Indicators:

- Tumor size < 2 cm

- No lymph node involvement

- Clean surgical margins

- Low histological grade

- No visible metastasis

In these cases, median survival times can exceed 2–3 years with surgery alone, and even longer with adjunctive treatments. Some cats achieve full remission and never relapse.

Unfavorable Prognostic Indicators:

- Tumor size > 3 cm

- Skin ulceration or muscle invasion

- Positive lymph nodes

- Incomplete resection

- Evidence of metastasis

For these cats, median survival times may drop to 6–12 months, though this is not a hard limit. With chemotherapy and palliative care, quality of life can still be maintained, and time meaningfully extended.

You might also want to check out our guide on Fungating Breast Tumors, especially if you’re dealing with ulcerated or open masses.

A note on statistics: they are averages, not destinies. They do not know your cat. They cannot account for her strength, your vigilance, or the nuances of care you’re able to provide.

Beyond the Numbers: The Value of Individualized Prognosis

Some readers will understandably want the black-and-white version: “Is my cat going to be okay?” Others are prepared to hear the shades of gray. Either way, one-size-fits-all estimates can be misleading.

That’s why staging shouldn’t be the end of the conversation—it should be the beginning of a personalized plan. A 10-year-old spayed Siamese with a 1.5 cm tumor and no nodal involvement is in a different prognostic category than a 12-year-old unspayed tabby with multiple fixed, ulcerated masses. The former may have years ahead. The latter may need a very different kind of support.

What matters most is that you’re equipped with the right information to choose what’s best—not just for the disease, but for your cat as a whole.

Treatment Options

Now comes the part where knowledge meets action. Once a diagnosis is confirmed and staging complete, you’re likely standing at a crossroad: What now? What’s the right next step for your cat—not in theory, not for some hypothetical feline, but for your cat?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer here, but there are well-defined strategies. Feline mammary cancer doesn’t lend itself to watchful waiting. This is not a slow-moving disease. In most cases, the sooner you act, the more options you preserve—and the better the odds of meaningful control or even remission.

Let’s start where most veterinarians do: with surgery.

Surgery: Still the Cornerstone

When it comes to feline mammary tumors, surgery remains the single most effective treatment—especially when done early and aggressively.

But—and this is important—not all surgeries are created equal. The traditional “lumpectomy,” or simple removal of a single mass, often falls short. That’s because of how these tumors behave: they like to travel along the mammary chain, jumping from one gland to the next, and even infiltrating the spaces between. What looks like one discrete mass is often just the most visible outpost of a much larger cellular invasion.

That’s why the standard of care is often one of the following:

- Unilateral mastectomy: Removal of all four mammary glands on the affected side.

- Bilateral staged mastectomy: Removal of all eight glands, done in two surgeries spaced several weeks apart to reduce anesthetic risk.

Why so aggressive? Because recurrence rates are significantly lower when the entire chain is removed. Leaving adjacent glands behind increases the chance that microscopic tumor cells will continue to grow—undoing the benefit of surgery.

Some owners worry this sounds extreme. “Isn’t that overkill? Won’t she suffer?” But cats, surprisingly, recover well from these procedures. Pain control is excellent, surgical sites heal quickly in most cases, and with proper care, complications are uncommon. The key is working with a vet who is experienced in this kind of oncology surgery.

Clean Margins: What They Really Mean

You’ll often hear the term “clean margins” thrown around. This refers to the edges of the tissue removed during surgery. If cancer cells are found at or near the edge, the margin is considered “dirty,” and it means some cancer was likely left behind.

Clean margins are the surgical gold standard. They’re strongly associated with longer disease-free intervals. If your pathology report says margins are clean, it’s one of the best pieces of news you can get post-op. If not, it doesn’t mean failure—but it does mean follow-up treatment becomes more important.

Which brings us to the next layer of care.

Chemotherapy: Not the Enemy

Chemotherapy in veterinary medicine is not like it is in human oncology. The goal is different: it’s not to obliterate the immune system in the name of total eradication. It’s about slowing down tumor growth, reducing recurrence, and prolonging quality life.

The most commonly used chemo agents for feline mammary cancer include:

- Doxorubicin (the heavy hitter): effective but carries a small risk of cardiotoxicity, especially in older cats.

- Cyclophosphamide and 5-fluorouracil: sometimes used in combination protocols.

- Carboplatin or mitoxantrone: alternatives in select cases.

Chemotherapy is typically recommended when:

- The tumor is large or high grade

- Surgical margins are incomplete

- There’s lymph node involvement

- There’s known metastasis

It’s usually given every 3 weeks for several cycles. Many cats tolerate it remarkably well, with minimal side effects—mild GI upset, slight lethargy, maybe a day or two of not quite being themselves. Severe reactions are rare, and quality of life is front and center.

Still, not every cat is a chemo candidate. Frail cats, those with other chronic conditions, or families unable to commit to the financial or logistical demands may opt out—and that’s okay. Which is why supportive and palliative options matter, too.

Radiation Therapy: Rare, but Worth Discussing

Radiation isn’t commonly used for feline mammary tumors. The logistics are intense—multiple sedated sessions at specialized facilities—and its use is generally reserved for:

- Incompletely excised tumors that can’t be re-operated

- Palliation of painful or locally invasive masses

If you’re near a veterinary radiation center and your case is complex, it’s worth at least consulting to understand your options. But for most cats, surgery and chemo are the pillars.

Palliative and Supportive Care: A Vital Piece, Not a Cop-Out

Sometimes, despite our best efforts, the disease is advanced. Or maybe your cat is too elderly or frail for aggressive treatment. Or perhaps you’ve made the deeply personal decision not to pursue surgery or chemo. In these cases, palliative care becomes the treatment plan, not the absence of one.

This includes:

- Pain management: Using NSAIDs like meloxicam (if kidneys allow), or opioids for more advanced discomfort.

- Anti-inflammatory therapies: Occasionally corticosteroids can shrink tumors slightly and improve comfort.

- Nutritional support: Encouraging appetite, managing nausea, and maintaining hydration.

- Wound care: If tumors ulcerate, keeping them clean and reducing odor or infection is crucial for your cat’s comfort.

Cats don’t fear death the way we do. But they do fear pain, isolation, and loss of dignity. Good palliative care honors their needs with the same urgency as any curative protocol.

Treatment is never just a medical decision—it’s emotional, financial, ethical, and deeply personal. The “right” plan is the one that balances clinical effectiveness with your cat’s unique condition and your own ability to provide care.

In the next section, we’ll talk about preventive measures—what you can do before cancer ever appears, or what you can still do now to reduce recurrence risk. Because even in the shadow of disease, there are always steps forward.

Preventive Measures

Let’s shift focus for a moment. After the emotional gravity of diagnosis, staging, and treatment, prevention might sound like a luxury—something to think about only if you’re starting fresh, with a younger cat, or maybe with a future pet. But prevention isn’t just a theoretical exercise. It’s deeply practical, often overlooked, and in the case of feline mammary cancer, it’s astonishingly effective.

Because here’s the rarely emphasized truth: this is one of the few cancers in cats that is, in many cases, truly preventable.

Early Spaying: The Single Most Powerful Preventive Tool

If you take only one thing away from this section, let it be this: the age at which a female cat is spayed is directly correlated with her lifetime risk of developing mammary cancer. Not just loosely. Not just vaguely. Quantifiably and dramatically.

The numbers are unambiguous:

- Spaying before 6 months of age reduces the risk by up to 91%.

- Spaying before 1 year still confers a roughly 86% risk reduction.

- After the first heat cycle, the protective effect drops sharply.

- After age 2, the impact of spaying on mammary cancer risk is minimal.

Let that sink in. A simple surgical procedure—already widely recommended for other health and population control reasons—can nearly eliminate a leading cause of feline cancer, if done early enough.

So why doesn’t this get more attention?

Partly because of misconceptions: some owners still believe cats should go through a heat cycle or have one litter “for their health.” These ideas are outdated and unsupported by science. In fact, allowing heat cycles increases estrogen exposure, which directly stimulates mammary tissue—and potentially, tumor formation down the line.

Another factor? Timing. People adopt cats at different ages, and not all come to their homes as kittens. Many are rescued as adults or from uncertain backgrounds, already beyond that golden prevention window. That doesn’t mean they’re doomed—it just shifts the focus from prevention to vigilance.

Weight Management: A Quiet Influence

Obesity isn’t a direct cause of mammary tumors, but it is an important modifier. Excess body fat alters hormone metabolism, increases inflammation, and affects immune surveillance—factors that can potentially influence cancer development and progression.

In particular, early-life obesity has been suggested to increase the risk of hormone-sensitive tumors. That means feeding habits in the first few years of life might lay the groundwork for future disease—even in the absence of other risk factors.

Maintaining a lean body condition throughout life doesn’t just help with joints and diabetes—it may also contribute to cancer prevention. And unlike many other cancer risk factors, this one is entirely within your control.

Environmental Estrogens and Hormone Use

Here’s something few owners consider: external hormone exposure. Products containing estrogen-like compounds—whether topical creams used by humans, environmental contaminants, or outdated hormone-based therapies given to pets—can all, in theory, affect mammary tissue.

While veterinary use of progestins (like megestrol acetate) has declined, they’re still sometimes prescribed for heat suppression or behavior control. Long-term use has been linked to mammary hyperplasia and tumor development, especially in intact females. Their use should be carefully evaluated and, in most cases, avoided.

And while rare, secondary exposure to topical hormone products (like HRT creams used by humans) has been reported to cause changes in companion animals. If you use hormone products on your own skin, be mindful of where and how you interact with your pets afterward.

Vigilance in High-Risk Cats

For unspayed or late-spayed cats, or breeds with known predispositions (such as Siamese), prevention looks less like shielding and more like early detection protocols.

That means:

- Monthly abdominal exams by you at home. You’re the one most likely to notice a small change.

- Annual (or semiannual) vet visits with palpation of the mammary chain.

- Clear documentation of any new lumps, with prompt evaluation of even tiny nodules.

It’s tempting to adopt a wait-and-see approach with small lumps—especially if your cat seems fine. But this is a disease where centimeters matter. Tumor size at detection can be the difference between a one-time surgery and a year-long oncology protocol.

Early detection is the next best thing to prevention.

Preventive Measures Post-Treatment

If your cat has already had a mammary tumor removed, prevention shifts into the realm of recurrence risk reduction.

Here’s what that involves:

- Complete surgical removal of all affected and potentially at-risk tissue. If a partial mastectomy was done previously, a follow-up surgery may still be advisable.

- Spaying post-diagnosis, if not already done. While late spaying won’t undo prior hormone exposure, it can reduce hormone-driven recurrence or secondary tumor formation.

- Regular surveillance imaging, especially in high-grade or node-positive cases. Chest radiographs every 6–12 months can catch metastasis early, when palliative interventions may still have impact.

- Consistent home monitoring, including regular body condition scoring, dietary review, and attention to subtle changes in energy or behavior.

Prevention, in this context, isn’t a one-time decision—it’s a long-term mindset.

In feline mammary cancer, prevention is one of the few tools that feels like a genuine win—clear, evidence-based, accessible. Whether you’re trying to avoid ever facing this disease, or ensuring it doesn’t return, your actions matter more than you think.

Coming up next, we’ll address one of the hardest questions an owner might ever face: When to consider euthanasia—how to recognize suffering, how to evaluate quality of life, and how to navigate this painful but profoundly humane decision with clarity and compassion.

When to Consider Euthanasia

No one wants to read this part. And yet, if you’re here, it means you’re facing something real—something that may already be pressing at the edges of every vet visit, every new symptom, every exhausted moment spent wondering if you’re doing enough. Or too much. Or both.

Let’s be clear: euthanasia is not about giving up. It’s about choosing dignity when medicine has run its course. It’s about honoring the unspoken agreement we make with our animals—that we will protect them from suffering when they can no longer protect themselves. This is the hardest chapter of care. And also, arguably, the most sacred.

Recognizing When the Balance Shifts

Mammary cancer, especially in its advanced stages, can be relentless. It doesn’t always progress in a linear, predictable way. A cat may seem relatively stable—still eating, still jumping to her favorite spot on the windowsill—and then, suddenly, the tide turns. A mass ulcerates and becomes infected. Metastasis to the lungs makes every breath feel labored. A once-manageable discomfort becomes persistent pain that breaks through medication.

The question isn’t simply “Is my cat dying?” The more useful question is: “Is she still living well?”

Living well isn’t just about whether your cat eats or purrs when petted. It’s about the full picture: mobility, grooming, curiosity, interaction, restfulness, and, crucially, the absence of unmanageable distress. A cat who hides more than she engages, who pants after walking across the room, who resists touch or neglects the litter box, is telling you something important—even if she never meows in complaint.

And cats don’t complain. They withdraw. Which is why we, as their guardians, must learn to read the subtleties.

Tools for Assessing Quality of Life

There are formal scales designed to help with this: the H3A Quality of Life Scale, for example, or the HHHHHMM Scale (Hurt, Hunger, Hydration, Hygiene, Happiness, Mobility, More Good Days Than Bad). These tools are not perfect, but they provide a framework—something objective to lean on when emotions blur your clarity.

If you’re finding yourself counting “good days” vs “bad days,” that’s already a sign that you’re doing the right kind of soul-searching. Many vets agree: when the bad days outnumber the good, consistently, that’s when it’s time to prepare.

Still, it’s not always about an obvious tipping point. Sometimes the decision emerges from a slow accumulation of small losses—a kind of quiet erosion. The light dims, gradually. The spark that made your cat herself becomes flickering and faint.

That, too, is valid. Death does not need to come in the form of a crisis to be real.

Physical Signs That Warrant Serious Consideration

Some indicators strongly suggest that your cat may no longer be experiencing an acceptable quality of life:

- Ulcerated tumors that won’t heal, emit foul odor, or bleed excessively

- Chronic, unresponsive pain, even with medications

- Labored breathing, especially if due to pleural effusion (fluid in the lungs)

- Complete loss of appetite, especially coupled with muscle wasting

- Severe lethargy, disinterest in surroundings, or isolation from family

- Loss of litter box habits due to mobility issues or cognitive changes

- Signs of confusion or distress, such as pacing or vocalizing at odd hours

It’s not about any one of these signs in isolation—it’s the pattern that matters. And if you find yourself needing to medicate just to keep your cat “comfortable enough,” day after day, it’s fair to ask whether comfort is truly being achieved… or just barely maintained.

The Role of Veterinary Guidance

You don’t have to make this decision alone. A trusted veterinarian can help you read the signs, interpret subtle shifts, and provide an honest assessment. Not all vets will push the conversation forward—you may have to ask explicitly. But any vet who has walked with clients through cancer care will know that the question of euthanasia isn’t just medical; it’s moral. And it’s about love expressed through courage.

Ask them, not just “Is there more we can do?” but also “Would you do more if this were your own cat?” Their answer may give you the clarity you’re quietly craving.

The Act Itself: What It Looks Like, and Why It Matters

If you choose euthanasia, know that it can be a peaceful process. Many vets now offer in-home euthanasia, which can provide a gentler, more private farewell. If done in a clinic, efforts are typically made to keep the environment quiet and stress-free.

Most procedures begin with a heavy sedative that allows your cat to fall into a deep sleep. Only once she is completely unaware does the euthanasia injection follow. It is swift, and it is painless. And as hard as it is to witness, many owners find comfort in being present—offering one last touch, one final whisper of thanks, love, and release.

There is no shame in choosing not to be present either. Each family must find their own boundary between grief and strength. What matters most is that the end comes without fear, without suffering, and with your cat’s dignity intact.

The Emotional Aftermath

Grief is not linear. It doesn’t follow rules. And for many pet owners, the loss of a beloved cat is as sharp as any human bereavement. That bond was real. Your efforts were real. And no matter how prepared you think you are, loss has a way of knocking the wind out of you.

Let yourself feel it. Talk about it. Write it down. Share your cat’s story. And if you need to, seek support—from friends, from a counselor, from a grief group, or from a community of people who understand what it means to lose a companion who never judged, never asked questions, never did anything but love you in the quietest, purest ways.

Support and Resources

Cancer doesn’t just happen to cats—it happens to families. To people who rearrange their work schedules around vet appointments, who learn to give injections when they never imagined they could, who lie awake calculating what “doing the right thing” might look like in the messy, uncertain middle of a disease that keeps changing the rules.

If you’ve made it this far through the journey—diagnosis, treatment, or even end-of-life care—then you already know this isn’t a path anyone walks alone. Or shouldn’t have to. Because while feline mammary cancer is a clinical condition, its ripple effects are deeply human. This is where support matters—not just for your cat, but for you.

Finding the Right Veterinary Partners

It starts with having the right people on your side. General practice veterinarians are often your first—and most familiar—line of defense. Many are more than capable of guiding you through surgery, basic diagnostics, and long-term management. But when things get complex, you may find value in broadening the circle.

Veterinary oncologists are specialists who live and breathe cancer care. They understand the nuances of tumor behavior, chemo protocols, recurrence timelines, and how to tailor aggressive treatments without sacrificing compassion. If your vet recommends a referral, take it seriously. Even a one-time consultation with an oncologist can reframe your entire care strategy.

To locate a board-certified oncologist in your area, the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM)maintains a searchable database. Many teaching hospitals and specialty clinics also offer oncology services—even if you’re not near a major metro area, it’s worth calling to ask what’s accessible.

But credentials aside, what matters most is chemistry. The vet you trust is the one who hears your concerns without rushing, who speaks frankly but kindly, and who helps you feel just a little less alone when everything feels uncertain.

Financial Help: Because Love Has a Budget

This is the part people hate to talk about, but we need to: cancer care is expensive. Surgery alone can run hundreds to thousands of dollars. Chemotherapy, if pursued, adds up quickly. And that’s not even counting diagnostics, imaging, follow-ups, and palliative meds.

No one wants to put a price tag on care—but real life doesn’t always allow idealism. If you’re struggling with the costs, you are not a bad pet parent. You’re human. And there are resources that may help.

A few worth exploring:

- RedRover Relief: Offers financial assistance for urgent veterinary care.

- The Pet Fund: Supports non-emergency care for chronic conditions like cancer.

- Frankie’s Friends: Provides grants for life-saving or life-extending treatment.

- CareCredit or Scratchpay: Credit/payment options tailored for veterinary care.

Also, don’t underestimate the value of open conversations with your vet. Many clinics have internal funds for hardship cases, or may be willing to work with you on payment structures. But they can’t help if they don’t know you’re struggling. Advocating for your cat includes advocating for yourself.

Emotional and Community Support

You are, in all likelihood, holding an enormous amount of emotional weight right now. Guilt, grief, decision fatigue, anticipatory mourning—it adds up. Especially when the outside world doesn’t always understand. “It’s just a cat,” some people say. But you know better.

Fortunately, others do too. There are grief counselors who specialize in pet loss. Support groups—both online and in-person—that can hold space for what you’re going through without minimizing it. Some animal hospitals even employ social workers or grief facilitators who can check in with families after difficult diagnoses or euthanasia.

Here are a few places to start:

- Association for Pet Loss and Bereavement (APLB): Offers trained grief counselors and moderated support groups.

- Lap of Love: Provides both in-home euthanasia and grief resources, including one-on-one support.

- Pet Loss Community on Reddit: Peer support for those mourning the death (or anticipated loss) of a beloved animal companion.

Even a single conversation with someone who gets it can shift the emotional load. Don’t underestimate how deeply this kind of support can help you stay grounded and resilient—not just for your cat, but for yourself.

Taking Care of Yourself, Too

There’s something about caregiving that makes people forget they have bodies. That they, too, need sleep, nourishment, breaks, and—perhaps most urgently—permission to feel. Burnout is real. Compassion fatigue is real. You cannot give endlessly without pause.

So take the nap. Eat the actual meal instead of skipping dinner again. Let yourself cry in the car after the vet appointment. Let yourself feel relief and not shame when you finally make a hard decision. Because loving an animal all the way to the end is not weakness—it’s a form of grace most people never learn.

And when the time comes to say goodbye, and the house feels too quiet and the routines collapse around the space your cat used to fill, remember this: the love doesn’t end. It just changes shape.

Next, we’ll round out this journey with a Frequently Asked Questions section—addressing common queries that arise at different stages of the feline mammary cancer journey—and then close with some final thoughts on how to move forward, no matter where you are in the process.

For pet owners navigating similar conditions, our resource on Hyperthermia for Treating Breast Cancer in Dogsgoes deeper into treatment options on the veterinary side.

Frequently Asked Questions

Even when you’ve done your research, absorbed the science, and talked with your vet, certain questions tend to hover. Some are practical. Others are deeply emotional. All are valid. Rather than reduce them to a list of bullet points and answers, let’s walk through the themes that tend to surface—sometimes whispered at the end of a visit, sometimes typed into search bars at 2 a.m.—with the depth and thought they deserve.

Because the truth is, the questions we ask when we’re caring for a sick cat often aren’t just about medicine. They’re about uncertainty. About hope. About trying to make the best decisions possible in a space where there are rarely clean answers.

Survival Time: What Can I Expect?

The first question that tends to arise after a diagnosis is: How long do we have? It’s natural to want a timeline—something concrete to plan around. But feline mammary cancer doesn’t hand out neat expiration dates. Prognosis is influenced by so many variables: the size and grade of the tumor, whether margins were clean after surgery, if lymph nodes were involved, whether chemo is pursued, and how your cat responds to care.

Still, there are patterns. Cats with small, localized tumors (under 2 cm) and no metastasis who undergo full mastectomy can live 2 to 3 years or more, sometimes with complete remission. Those with more advanced disease—larger tumors, lymph node involvement, or visible metastasis—often face a more limited window, sometimes 6 to 12 months, even with treatment.

But remember: these are medians, not guarantees. Every cat is a universe. Some defy expectations. Some decline quickly despite all efforts. You don’t need to chase a number—you need to stay close to your cat’s quality of life and let that be your compass.

Can This Happen Again?

Unfortunately, yes. Feline mammary cancer has a high recurrence rate, especially if surgery was limited or margins were not clean. Even after full mastectomy, new tumors can emerge in the opposite chain or in tissue left behind. That’s why surveillance doesn’t stop after treatment. Regular check-ups, chest X-rays every 6–12 months, and monthly at-home palpation are part of the long game.

And if your cat is still intact, spaying post-diagnosis may help reduce recurrence—even if it’s late. Hormones fuel this cancer, and removing that fuel source, even after the fact, can slow its progression.

What if I Missed the Signs Until It Was Too Late?

There’s a particular guilt that hits when you feel you should’ve noticed sooner. Maybe the lump was there for a while. Maybe your cat started hiding more, and you chalked it up to aging. Maybe you were told it was benign—until it wasn’t.

Let me say this clearly: you are not a failure. You are not neglectful. You are not unloving.

Cats are extraordinarily skilled at masking symptoms. Mammary tumors can grow in silence, tucked beneath fur and fat. Even seasoned vets can mistake early ones for benign nodules. What matters is what you do now—not what you didn’t know then.

Is Chemotherapy Worth It?

This is less a question about science and more about values. In veterinary medicine, chemo is often more tolerable than people expect. Side effects are typically mild, quality of life is prioritized, and many cats sail through treatment with barely a blip.

But it’s not for everyone. Financial constraints, other health conditions, travel demands, or just a cat’s personality might tip the scale in favor of comfort care instead. The real question is: Will this treatment add something meaningful to her life? If the answer is yes—more time, more comfort, more clarity—then it’s worth considering. If not, that’s okay too.

There is no “right” choice. Only the one that fits your cat, your family, your context.

Should I Get a Second Opinion?

If you’re unsure about a diagnosis, treatment plan, or prognosis, seeking a second opinion isn’t disloyal or excessive—it’s wise. Especially with aggressive cancers like this, having an oncologist weigh in can either confirm your current path or open new options.

More than once, second opinions have caught early metastasis missed on initial X-rays, or identified surgical plans that could be expanded for better margin control. If your gut says you need more clarity, listen to it.

Closing Thoughts

If you’ve made it this far—through diagnosis, staging, treatment options, and those impossible conversations about euthanasia—then this journey has already changed you. Not just in how you see your cat, but in how you understand devotion, resilience, and the quiet bravery of letting go.

Feline mammary cancer isn’t just a diagnosis. It’s a lived experience. It demands time, money, clarity, and emotional strength. It pulls you into decisions you never thought you’d face—and teaches you what it really means to advocate, to care, and to act when there are no perfect choices.

That’s why this article exists: to give you the full picture. Not fragments. Not vague suggestions. But real tools, real language, and real understanding—so you could approach every decision with eyes open, heart steady, and mind informed.

And now, you do.

You understand how this cancer behaves, how it spreads, what treatment involves, and what comfort care means. You know what staging numbers suggest, what margins tell us, and how prognosis shifts with each variable. But more than that, you’ve seen that every clinical choice is also an emotional one—tethered to love, ethics, finances, and fear.

Whether you choose surgery or not… chemo or comfort… a final car ride or one more round of medication—every decision you’ve made, or will make, is an expression of love.

Not the easy, photogenic kind. The kind that shows up in daily caregiving. In vigilant watching. In knowing when to fight and when to stop. In being there when they take their last breath, so they don’t have to leave the world alone.

There is no one right path through this. But if you’ve shown up fully—if you’ve made your cat feel safe, seen, and cherished—then you’ve already done the hardest, most beautiful part.

You gave her that.

And that is everything.

So wherever you are in the process—mid-treatment, in recovery, or grieving a cat who’s already gone—know this: you did enough. You are not alone. Her story matters. And the love you gave her doesn’t end here—it becomes part of you. A soft echo of all the ways you showed up.

That’s the legacy worth holding onto. Not just the medical outcomes, but the quiet, unwavering care that carried you both through.