Can Vitamin Deficiencies Indicate Cancer? What the Science Says

- Foreword

- Part One: When the Body Signals Something — But Not Always Clearly

- Part Two: Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Cancer

- Part Three: Low Potassium and Cancer

- Part Four: High RDW and Cancer

- Part Five: Microcytic Anemia and Cancer

- Part Six: When Should You Be Concerned?

- Part Seven: What the Research Actually Says

- Part Eight: Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

Most people don’t expect cancer to announce itself in numbers. You go in for routine bloodwork — maybe for fatigue, dizziness, or just an annual checkup — and something’s off. Your vitamin B12 is low. Or your potassium is dropping. Maybe your red blood cell size is off, or your RDW is flagged. It’s not a diagnosis. It’s not even a direction. But it’s a crack in the glass — something not quite right.

That’s usually when the questions start. Could this mean something more serious? Could it be cancer?

The truth is, some cancers do speak through bloodwork long before they show up on scans. But most of the time, vitamin and mineral deficiencies aren’t a warning siren — they’re a whisper. They point to patterns: how your body’s processing nutrients, how cells are dividing, what’s being lost, or what’s not being absorbed. In rare cases, those patterns hint at something hidden — an internal tumor, a bleeding lesion, a disrupted marrow. In far more cases, they point to more common causes: malabsorption, aging, diet, medications, or chronic inflammation.

Still, the worry is understandable. There’s a kind of quiet alarm built into abnormal lab results, even when no one says the word “cancer” out loud. And that anxiety can be made worse by what you find online: search results filled with worst-case scenarios, studies without context, and message boards where one person’s rare diagnosis becomes another’s fixation.

This article was written to step in there — in the space between “my labs were off” and “what does this mean?” It’s not here to downplay risk, but to explain it. To show where science draws real connections, and where it doesn’t. To clarify why a single low number almost never tells the full story — and when it might be a clue worth following.

We’ll walk through each of the major concerns that commonly come up in this context:

Can B12 deficiency signal cancer? What does low potassium really suggest? Does high RDW mean something serious? And when does microcytic anemia — small, iron-poor red cells — actually lead to a cancer diagnosis?

We’ll also talk about what to do with that information. Because while bloodwork can sometimes be an early warning sign, it’s rarely the final word. It’s the beginning of a process — one that needs history, imaging, sometimes scopes, and always context.

So if you’re here with lab results that don’t make sense yet — or if you’re trying to figure out what kind of attention your symptoms really deserve — you’re in the right place. What follows won’t give you instant clarity. But it will give you the tools to ask the right questions, understand the stakes, and move forward from concern into action.

Let’s begin.

Part One: When the Body Signals Something — But Not Always Clearly

The human body doesn’t tend to shout when something’s wrong. It nudges. It shifts. It drifts slightly out of balance — through fatigue that doesn’t go away, bruises that show up too easily, a heart that beats a little too fast after standing up. Or it signals quietly in the numbers: bloodwork that comes back with one line in red, or a value marked low when it wasn’t the year before.

That’s where most stories like this begin — not with symptoms so dramatic they force a diagnosis, but with patterns that don’t quite fit. Your vitamin B12 is low. Your red blood cells are too small. Your potassium dips just below the normal range. You may not feel different at all. Or you might feel something that’s hard to describe — a tiredness, a mental fog, a physical heaviness that could mean anything, or nothing.

This is the gray area doctors navigate every day. Because while lab tests are precise, their interpretations never exist in isolation. A low B12 level could come from years of gradual dietary deficiency, or from a newly developed autoimmune condition. It could mean your stomach isn’t absorbing properly, or your bone marrow isn’t producing normally. And in a small number of cases, it might mean something deeper is disrupting the system — including cancer.

But this isn’t usually how cancer starts. Most cancers don’t announce themselves in a single blood test. They begin in cells, tissues, or organs — growing silently, gradually — and only later do they leave a visible trail: iron loss from slow bleeding, vitamin depletion from malabsorption, or electrolyte shifts from metabolic strain. Even then, the body often adapts for a while. That’s why abnormal lab values often show up alongside, not ahead of, symptoms or clinical context.

Still, in oncology, lab results do matter. They can provide early clues, sometimes long before imaging or symptoms catch up. A string of mild abnormalities — nothing dramatic on their own — might prompt a physician to look deeper. Especially if the pattern holds over time, or if the patient is older, has unexplained weight loss, or comes from a family with a history of malignancies. In that way, lab work becomes a kind of subtle map — not definitive, but suggestive. Not a diagnosis, but a direction.

It’s also worth noting that the majority of vitamin deficiencies and lab abnormalities are not caused by cancer. They’re far more likely to reflect chronic inflammation, autoimmune conditions, gastrointestinal issues, aging, medications, or diet. But dismissing them entirely would also be wrong — especially when they’re new, persistent, or accompanied by other red flags.

This is the space we’ll be exploring in the sections ahead. We’re not drawing straight lines between low nutrients and malignancy — because in most cases, those lines don’t exist. Instead, we’ll examine the associations: where science has found meaningful overlap, where abnormalities have led to early detection, and where the relationship is still speculative.

Because what your blood says matters — but it matters most when you understand what it’s trying to say, and what it’s not.

Part Two: Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Cancer

Vitamin B12 isn’t just a supplement aisle staple — it’s an essential molecule with wide-ranging responsibilities in the body. It helps build DNA. It’s central to red blood cell formation. It keeps nerves functioning and your brain stable. When B12 runs low, the effects ripple through everything from cognition to energy levels to the basic ability to carry oxygen in the blood.

So when a lab test shows a low B12 level, doctors don’t just treat the number. They ask why.

And this is where the path can fork. Because B12 deficiency can be common, harmless, and reversible — or it can be a signal of something deeper. Sometimes the cause is dietary, especially in vegans, vegetarians, or elderly adults with low meat intake. Other times, it stems from medications like metformin or long-term antacids, which interfere with absorption. But in certain situations — and this is where the keyword lands — a persistent or unexplained B12 deficiency may be an early clue to an underlying cancer.

So, can vitamin B12 deficiency be a sign of cancer? In some cases, yes — but not in the way most people imagine. Let’s break that down.

How the Body Absorbs B12 — and Where It Can Break Down

B12 absorption depends on a surprisingly complex process. It begins in the stomach, where hydrochloric acid helps release B12 from food proteins. The free B12 then binds to a protein called intrinsic factor, secreted by specialized cells in the stomach lining. This B12–intrinsic factor complex then travels to the end of the small intestine — specifically the terminal ileum — where it’s absorbed into the bloodstream.

If any part of that chain breaks, B12 levels can fall. Damage to the stomach lining, for example, reduces acid and intrinsic factor production. Diseases affecting the ileum — such as Crohn’s disease or surgical removal — block absorption. And autoimmune conditions like pernicious anemia destroy intrinsic factor-producing cells altogether.

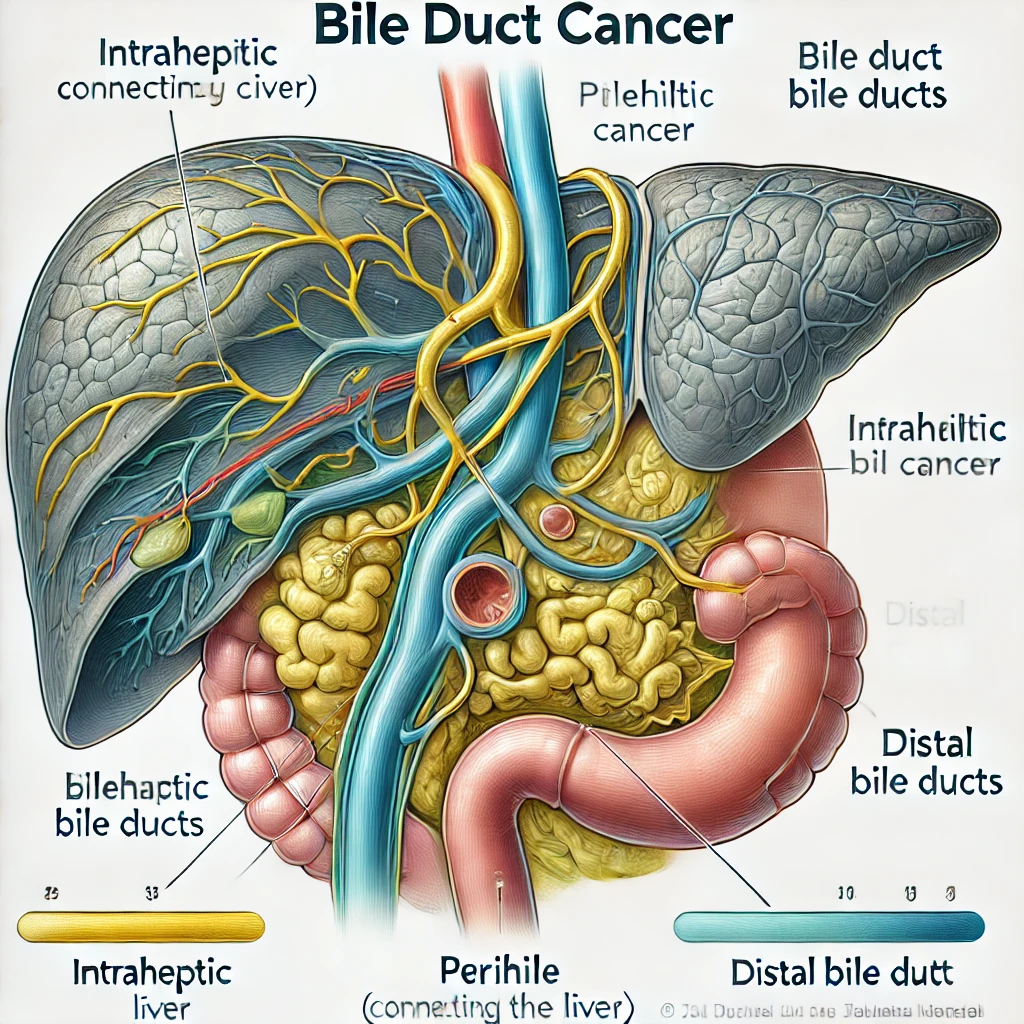

Why does that matter for cancer? Because some cancers — especially in the stomach and small intestine — disrupt this exact process.

Gastric Cancer and B12 Malabsorption

One of the clearest links between B12 deficiency and cancer comes from the stomach. Long-term inflammation of the gastric lining, known as chronic atrophic gastritis, can lead to thinning of the stomach wall, loss of acid production, and destruction of intrinsic factor–producing cells. This condition is often asymptomatic in early stages — people may feel only mild fatigue or indigestion — but over time, it can lead to both pernicious anemia and increased gastric cancer risk.

So when a patient is found to have B12 deficiency due to intrinsic factor loss, doctors may investigate further. In some cases, that workup uncovers early-stage gastric cancer. It’s not that the low B12 level itself signals cancer — it’s that it reveals a failure of the stomach’s normal function, and that failure prompts a deeper look.

In this way, B12 deficiency can function as an indirect marker. It’s not the cancer speaking — it’s the body struggling to keep up with what the cancer is disrupting.

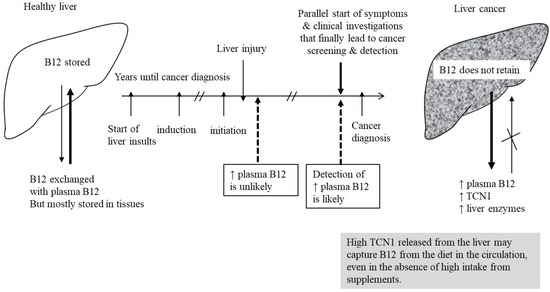

B12 and Hematologic Malignancies

There’s another, more complex link between B12 and cancer — one that comes from blood cancers, like leukemia and lymphoma. In these diseases, the bone marrow becomes disordered, flooded with abnormal cells that disrupt normal blood production. As part of that disarray, the body may consume B12 rapidly, or fail to use it effectively.

Sometimes, patients with leukemia or high-grade lymphoma present with signs that look like B12 deficiency — including megaloblastic anemia (large, immature red cells), neurological symptoms, or fatigue. Blood tests may show a B12 level that appears normal, but functionally the vitamin isn’t being used. In some cases, B12 is actually elevated — not low — but still not metabolized properly. These are clues that the problem isn’t dietary or absorption-related, but marrow-based.

So again, B12 isn’t the smoking gun. But changes in B12 status — especially when paired with abnormal blood counts or symptoms like weight loss, night sweats, or bone pain — may help direct attention toward a hematologic cancer diagnosis.

When Should Low B12 Raise Concern?

A single low B12 level, by itself, doesn’t mean cancer. But there are certain situations where it deserves more scrutiny:

- In older adults, especially those with no dietary explanation for the deficiency

- When accompanied by macrocytic anemia (large red blood cells on a CBC)

- In patients with known autoimmune conditions — particularly type 1 diabetes or thyroid disease

- When the deficiency persists despite supplementation, or when neurological symptoms appear before anemia

- If there’s chronic indigestion, early satiety, or unintended weight loss — symptoms sometimes associated with stomach pathology

In these cases, doctors may recommend a gastric biopsy, upper endoscopy, or further autoimmune testing to evaluate for underlying atrophic gastritis or malignancy.

B12 deficiency is common. Cancer is not. But when B12 runs low for unclear reasons — and especially when it resists correction — it opens the door to more questions. Sometimes, those questions save lives. And that’s why this small vitamin earns such serious attention.

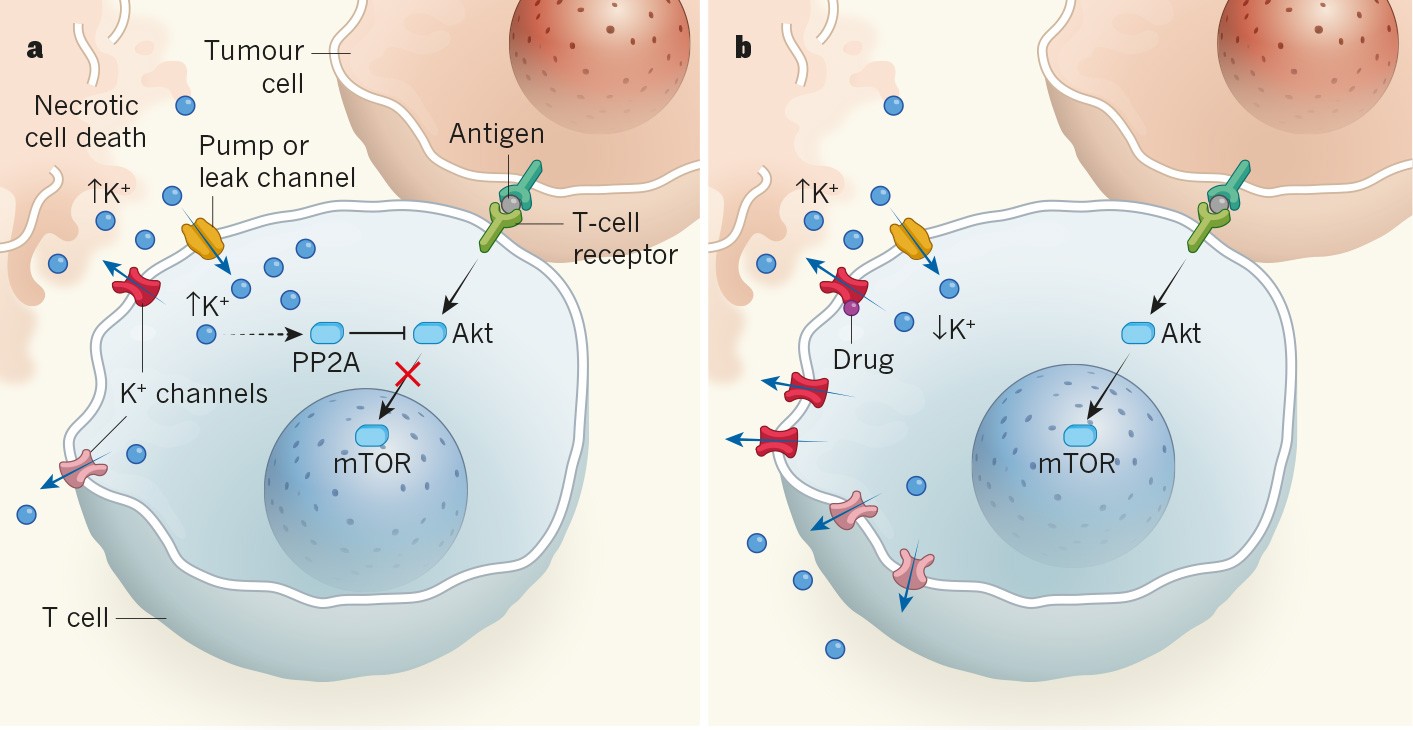

Part Three: Low Potassium and Cancer

Potassium isn’t something most people think about — until the numbers dip. It’s not a vitamin. You don’t track it in your diet the way you do with iron or B12. But in the body, potassium does quiet, essential work every second: maintaining fluid balance, stabilizing blood pressure, and, most critically, keeping your heart and muscles firing rhythmically. When levels fall below normal — a state called hypokalemia — things don’t break immediately, but they do falter.

Mild hypokalemia can cause fatigue, muscle weakness, or cramps. Severe drops can trigger arrhythmias, numbness, and, in extreme cases, paralysis or cardiac arrest. But the real concern isn’t just the number — it’s why the number is low in the first place.

So: is low potassium a sign of cancer? On its own, almost never. But in context — especially in someone undergoing cancer treatment, or with a constellation of unexplained symptoms — low potassium can point toward certain malignancies or cancer-related syndromes. Let’s look more closely at what that means.

The Physiology of Potassium Loss

Potassium levels are tightly regulated. Most of the potassium in the body lives inside cells, not in the bloodstream. So when serum potassium drops, it’s often because of one of three things:

- Loss through the GI tract — via vomiting, diarrhea, or fistulas

- Loss through the kidneys — often triggered by diuretics, hormonal imbalances, or renal tubular disorders

- Shifts into cells — such as during insulin surges or certain metabolic conditions

Cancer can intersect with any of these — though usually indirectly. That’s why hypokalemia isn’t typically a direct sign of cancer, but rather a consequence of what cancer does to the body.

How Cancer Can Cause Low Potassium

There are several ways a malignancy might lead to persistent hypokalemia, especially when the tumor burden is high or the cancer affects hormone-secreting organs:

1. Gastrointestinal Cancers and Vomiting

Cancers of the stomach, pancreas, or intestines may lead to chronic vomiting or diarrhea, either due to the tumor itself or secondary to treatment. Loss of fluids leads to loss of electrolytes, and potassium is one of the first to go.

2. Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Some cancers, especially small cell lung cancer or renal cell carcinoma, produce hormones or hormone-like substances that interfere with the normal regulation of salt and water. This can mimic conditions like hyperaldosteronism, which causes the kidneys to excrete too much potassium. Though rare, these syndromes can lead to persistent, unexplained hypokalemia and may be part of a broader diagnostic picture.

3. Tumor Lysis Syndrome

In aggressive blood cancers like acute leukemia or high-grade lymphoma, rapid tumor cell death — either spontaneous or after chemotherapy — can flood the bloodstream with intracellular contents. This can shift potassium into or out of cells unpredictably, sometimes leading to transient low levels during the early phase of cell breakdown. It’s a dangerous complication, but typically happens after diagnosis and treatment has already begun.

4. Medications in Cancer Care

Often, it’s not the cancer itself, but the treatment that lowers potassium. Chemotherapy, corticosteroids, and certain targeted therapies can affect kidney handling of electrolytes. Diuretics, frequently used for fluid buildup in patients with advanced disease, also cause potassium loss unless paired with a potassium-sparing agent.

Low Potassium in Cancer Patients vs. the General Population

Among people without a cancer diagnosis, low potassium is most often explained by non-malignant causes: chronic diarrhea, overuse of laxatives, excessive sweating, or medications like loop diuretics. In older adults, inadequate dietary intake and polypharmacy often intersect.

In people with known or suspected cancer, hypokalemia is more likely to be a consequence of the disease state — especially in advanced or metastatic settings. It may reflect tumor activity, treatment effects, or complications like obstruction or adrenal involvement. That’s why, in cancer care, potassium levels are checked frequently and corrected aggressively. Even mild deficits can destabilize an already strained system.

When Low Potassium Should Prompt Concern

So if potassium is low — what should that mean to you, as a patient or clinician?

If it’s an isolated finding, in an otherwise healthy person, with a clear cause (such as a recent stomach bug, or a diuretic prescription), it may not need more than correction and follow-up.

But if hypokalemia is:

- Persistent, despite replacement

- Unexplained, with no GI loss or medications

- Accompanied by other abnormalities (like metabolic alkalosis, muscle weakness, or abnormal cortisol levels)

- Part of a bigger pattern — such as weight loss, fatigue, or new imaging findings

…then deeper evaluation may be needed. Not necessarily for cancer right away, but for any condition that might be driving the loss, including tumors of the adrenal glands, kidneys, or lungs.

Potassium is a narrow signal — easy to overlook, but meaningful when persistent and unexplained. It’s rarely the first sign of cancer. But in the right context, it may be part of the body’s quiet reaction to something it’s already trying to manage. That’s what clinicians are trained to hear — not the single out-of-range value, but the overall tone.

Part Four: High RDW and Cancer

You won’t find Red Cell Distribution Width on the front page of most blood panels. It’s usually tucked away in the complete blood count (CBC), wedged between numbers most people are told to watch — hemoglobin, hematocrit, MCV. RDW doesn’t draw much attention unless it’s high, and even then, it rarely sparks urgent concern. But over the past decade, researchers have started paying closer attention to this quiet number — especially in cancer care.

So what is RDW, and why does it matter?

Put simply, RDW measures how varied your red blood cells are in size. A healthy blood sample shows mostly uniform red cells — all about the same diameter. But when production becomes disordered — whether due to nutrient deficiency, inflammation, or disease in the bone marrow — red cells start showing up in different sizes. That’s when RDW rises.

So the keyword question arises: is high RDW a sign of cancer?

Not directly. RDW isn’t a cancer marker. It doesn’t point to a tumor, and it can’t confirm a diagnosis. But it does reflect stress — physiological disruption — and in that way, it sometimes correlates with cancer’s presence, its aggressiveness, or its burden on the body. Let’s unpack that.

What Causes RDW to Go Up?

Several common conditions can elevate RDW — none of them cancer on their own:

- Iron deficiency anemia often leads to a mix of smaller and normal-sized red cells, raising RDW.

- Vitamin B12 or folate deficiency causes macrocytic anemia — and again, variation in cell size.

- Chronic inflammatory states — like rheumatoid arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease — can subtly disrupt red cell maturation.

- Liver disease, kidney disease, and heart failure have all been linked to high RDW in various studies.

- Aging itself tends to increase RDW slightly, especially past age 65.

In each of these cases, RDW isn’t pointing to one specific cause — just non-uniform red cell production. That’s why it’s often considered nonspecific but clinically useful when interpreted in context.

RDW and Cancer: What the Research Shows

In recent years, researchers have looked at RDW in people with known cancers — not to detect cancer, but to predict outcomes. And the patterns are surprisingly consistent.

Higher RDW levels have been associated with poorer prognosis in several cancers, including:

- Colorectal cancer

- Lung cancer

- Breast cancer

- Esophageal cancer

- Liver and gastric cancers

- Lymphomas

In these studies, patients with elevated RDW at the time of diagnosis often had more aggressive disease, higher levels of systemic inflammation, and worse overall survival. Some theories suggest that a high RDW reflects the body’s struggle to maintain red cell production in the face of chronic disease, oxidative stress, and tumor-related cytokine activity.

Again, this doesn’t mean RDW can tell you whether you have cancer — but if you already have cancer, RDW might give your doctors additional insight into how your body is responding.

Why RDW Isn’t a Screening Tool

Despite these associations, RDW is not — and should not be — used as a screening test for cancer. It’s too nonspecific. A high RDW could just as easily reflect a vitamin deficiency, an infection, or a chronic illness. Many completely healthy people have elevated RDW levels due to age or subclinical issues.

And on the flip side, many patients with early-stage or even advanced cancers have a normal RDW. It’s neither sensitive nor specific enough to stand alone. But it may be useful as a piece of the larger puzzle — especially when unexplained anemia is involved, or when a constellation of lab abnormalities points toward something more serious.

When Should a High RDW Prompt Further Testing?

It depends entirely on the clinical picture. A mildly elevated RDW in an otherwise healthy, asymptomatic person is rarely a cause for concern. But a high RDW combined with:

- Anemia that doesn’t respond to iron or B12

- Fatigue, weight loss, or GI symptoms

- Elevated inflammatory markers

- A personal or family history of cancer

… may warrant a more detailed workup. That might include vitamin levels, iron studies, colonoscopy, endoscopy, or imaging — not because RDW suggests cancer directly, but because the overall pattern raises the index of suspicion.

RDW is a background signal — subtle, broad, and easily ignored. But in the right context, it contributes to the story. It’s not a warning light, but it is a sign that something in the machinery isn’t running smoothly. And in medicine, those signs often lead to the answers we need — when we take the time to read them properly.

Part Five: Microcytic Anemia and Cancer

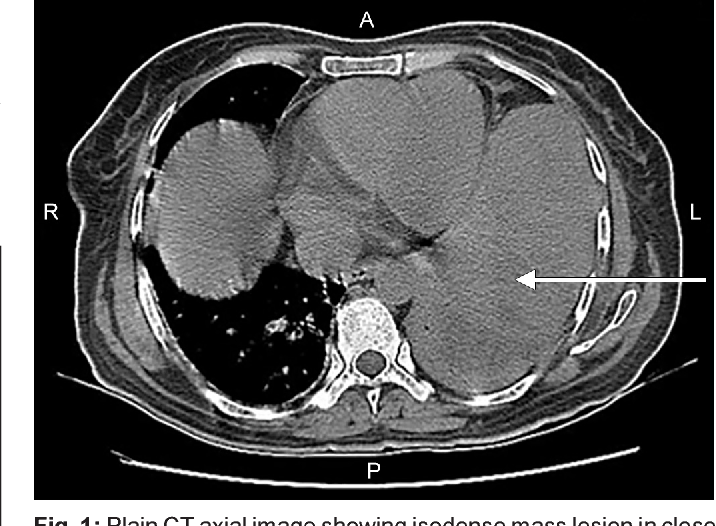

Red blood cells are small to begin with. But when they get smaller than they should be — and consistently so — it’s a signal that something fundamental has changed in how they’re being made. This is what we call microcytic anemia: anemia defined not just by low hemoglobin, but by red blood cells that are unusually small (with a low mean corpuscular volume, or MCV). The most common cause? Iron deficiency.

And most of the time, iron deficiency comes from something benign. Poor diet, heavy menstrual bleeding, pregnancy, or chronic blood loss from noncancerous gastrointestinal conditions. But when microcytic anemia appears in older adults, or when it shows up without a clear cause, it raises a different question: where is the blood going?

That’s where cancer comes into the picture — not as the first answer, but as a possibility that has to be considered. So when people ask, “Is microcytic anemia a sign of cancer?” the answer is: sometimes — and it’s one of the most important patterns clinicians are trained to recognize.

Iron, Red Cells, and the Problem of Loss

Red blood cells need iron to function. Without it, they can’t build hemoglobin — the molecule that binds oxygen. When iron runs low, the body still tries to make red cells, but they’re smaller and paler. The result is microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

Now, there are only a few causes of this:

- True iron deficiency from blood loss or poor intake

- Anemia of chronic disease, where iron is present but locked away by inflammation

- Genetic disorders like thalassemia (usually picked up earlier in life)

In adults, unexplained iron deficiency is always treated seriously — especially in men, postmenopausal women, or older patients without a clear dietary reason. That’s because one of the most common hidden causes of iron loss is slow gastrointestinal bleeding, and one of the leading sources of that is cancer — most often in the colon or stomach.

Colorectal Cancer and Microcytic Clues

Colorectal tumors — especially on the right side of the colon — often grow silently for months. They may not cause pain or obvious blood in the stool. But they can bleed slowly and chronically, leading to a gradual depletion of iron. The result: mild fatigue, shortness of breath, and microcytic anemia that might look “just borderline” on labs. No dramatic symptoms. Just numbers, quietly drifting.

This is why guidelines recommend colonoscopy in any adult with unexplained iron deficiency anemia. It’s not that every case will turn up cancer — far from it — but because when cancer is present, this is often how it first appears.

In fact, for many people, microcytic anemia is the first and only clinical sign of a right-sided colon cancer.

Stomach Cancer and Malabsorption

The stomach is another potential source. Gastric cancers may lead to blood loss through ulceration or erosion of the stomach lining. They may also interfere with iron absorption by altering gastric acid levels. In some cases, these tumors present similarly to atrophic gastritis or peptic ulcers — which is why endoscopy is often used alongside colonoscopy when evaluating iron deficiency in older adults.

It’s worth noting that microcytic anemia doesn’t always reflect iron deficiency alone. Inflammation from chronic illness — including cancer — can create a functional iron deficiency, where iron stores are present but inaccessible due to the body’s immune response. This type of anemia can still be microcytic, and it may overlap with true deficiency, complicating the picture.

When Should You Worry?

If microcytic anemia shows up on your labs, the next steps depend heavily on age, sex, history, and symptoms. Doctors will usually start with:

- Iron studies (serum iron, ferritin, transferrin saturation)

- Stool occult blood testing

- Endoscopy and colonoscopy, if no clear cause is found

- Celiac screening, especially in younger patients or those with GI symptoms

- Follow-up labs after iron replacement, to ensure correction

Cancer isn’t the most common cause. But it is the one that requires urgency — which is why even a subtle anemia is never dismissed in patients over 50. The phrase “microcytic anemia” may sound technical, but in practice, it often triggers a full diagnostic workup. Because in this case, a small red cell might be the first hint of a much larger problem.

Microcytic anemia isn’t a diagnosis. It’s a flag. And when it flies without clear reason, especially in older adults or those with new fatigue or GI symptoms, it opens a door that sometimes leads straight to early cancer detection — and a chance to intervene when it matters most.

Part Six: When Should You Be Concerned?

Not every abnormal lab result points to cancer. Most don’t. They point to something real, yes — something your body is working through or compensating for — but they’re more often signs of imbalance than invasion. Still, if you’re the patient reading that lab report, or the clinician deciding what to do next, the question remains: when is this just a lab quirk — and when is it a red flag?

The answer depends entirely on pattern, persistence, and context.

One-off values — especially if they’re only slightly out of range — usually don’t mean much by themselves. A borderline low B12 in a vegetarian? Not surprising. A low potassium after a stomach bug or a week on a diuretic? Common. A mildly elevated RDW in an older adult recovering from an illness? Possibly expected.

But when these changes don’t resolve, when they arrive without explanation, or when they’re accompanied by symptoms that don’t quite fit, they deserve more attention. It’s not about any one lab result being ominous. It’s about the accumulation of uncertainty.

The Patterns That Raise a Clinician’s Eyebrow

What starts to shift suspicion from nutritional imbalance to possible underlying disease?

- Persistence. If B12 stays low despite oral supplementation, or if microcytic anemia doesn’t improve after a full course of iron, something else may be blocking absorption or causing ongoing loss.

- Unexplained origin. If there’s no dietary, medication-related, or physiologic reason for the abnormality — no GI symptoms, no obvious blood loss, no autoimmune history — the cause becomes worth chasing.

- Combination with other changes. High RDW plus anemia. Low B12 plus neurologic symptoms. Hypokalemia plus metabolic alkalosis or muscle weakness. Each combination begins to outline a more complex picture.

- Accompanying systemic signs: unintended weight loss, fatigue that worsens rather than improves, night sweats, chronic indigestion, changes in bowel habits, or persistent pain.

- Age and risk profile. In patients over 50 — particularly men or postmenopausal women — doctors are more likely to consider a cancer workup for unexplained anemia, even in the absence of other symptoms. That’s not because cancer is the most likely cause, but because it’s the one you don’t want to miss.

What Happens When Doctors Decide to Look Deeper?

Escalating from bloodwork to further testing isn’t always dramatic. Often it begins with repeat labs, just to confirm the abnormality. From there, depending on what’s found:

- A colonoscopy or upper endoscopy may be ordered to evaluate for GI bleeding or tumors.

- Imaging studies (CT, ultrasound) may be used to look for organ-level causes or hidden lesions.

- Bone marrow biopsy may be considered if blood cell production is severely disrupted.

- Autoimmune testing or gastric biopsy may be performed if pernicious anemia or chronic gastritis is suspected.

Even when cancer is not found, these steps can uncover other important causes — like celiac disease, atrophic gastritis, early kidney dysfunction, or chronic inflammatory conditions that also deserve treatment.

Why Early Investigation Matters — Even If the News Isn’t Bad

The goal of early testing isn’t to confirm a fear. It’s to rule out the most serious possibilities first, so that the rest of the differential can be managed calmly. When cancer is the cause — especially colorectal or gastric tumors linked to anemia — catching it early makes a profound difference in outcome. And when it’s not, the peace of mind is real.

Unexplained lab abnormalities are never just numbers. They’re clinical stories still in the first chapter. Knowing when to turn the page — and when to pause and reread — is part of good medicine.

Part Seven: What the Research Actually Says

It’s easy to find studies linking vitamin deficiencies or lab abnormalities to cancer — just type the right keywords into a search engine, and you’ll see headlines claiming everything from “Low B12 Tied to Tumors” to “High RDW Linked to Cancer Mortality.” But research, like bloodwork, needs context. Associations aren’t explanations. And while the connections are real, they’re often more subtle — and more conditional — than they first appear.

Let’s walk through what the medical literature actually shows about these markers: not just whether they correlate with cancer, but how they do — and how researchers are interpreting those findings in real-world care.

B12 Deficiency: A Marker of Malabsorption or Marrow Dysfunction

The association between vitamin B12 deficiency and cancer is strongest in cases where the stomach or small intestineis involved. Studies have shown that gastric atrophy, which leads to B12 malabsorption, is also a risk factor for gastric adenocarcinoma — the most common form of stomach cancer. In populations with high rates of pernicious anemia, long-term follow-up reveals a moderately increased risk of developing gastric tumors.

B12 levels have also been studied in hematologic malignancies, particularly leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes, where the deficiency may reflect ineffective red cell production or increased turnover rather than malabsorption. In these cases, the functional deficit may not show up as low serum B12 but still appears in the cell’s inability to mature properly.

Importantly, B12 deficiency has not been shown to directly cause cancer — but in certain settings, it serves as a signal of underlying pathology that may include or predispose to malignancy.

Potassium Levels: More a Symptom Than a Signal

There’s far less direct research linking hypokalemia to cancer as an early marker. Most studies discuss potassium levels in the context of cancer complications — such as vomiting, diarrhea, renal loss, or tumor-related hormonal effects — rather than as an initiating clue. In hematologic cancers, for example, electrolyte shifts are common during tumor lysis syndrome, but this happens after diagnosis, usually during treatment.

In patients with adrenocortical tumors or ACTH-producing lung cancers, hypokalemia may be part of a broader endocrine syndrome (like Cushing’s), but again, it’s one feature among many — not a standalone indicator.

So while low potassium may flag a serious complication, it’s not a primary biomarker for early detection. It remains clinically important, but nonspecific.

High RDW: A Window Into Systemic Stress

Red Cell Distribution Width (RDW) has quietly become one of the more interesting metrics in cancer research. Numerous large-scale studies — including analyses from NHANES data and major cancer centers — have found that elevated RDW correlates with increased all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, even in asymptomatic individuals.

RDW appears to track with chronic inflammation, nutrient deficiencies, and bone marrow stress, which may explain its rise in cancer patients. In colorectal, breast, and lung cancers, high RDW has been associated with:

- Worse performance status

- More advanced staging

- Lower survival rates

But again, RDW isn’t specific enough to diagnose anything on its own. It’s likely a prognostic marker, not a diagnostic one — meaning it helps estimate outcome after diagnosis, not identify disease beforehand.

Microcytic Anemia: Stronger Evidence, Clearer Pathways

Among the lab markers in this article, microcytic anemia from iron deficiency has the strongest evidence base linking it to early cancer detection — particularly in the gastrointestinal tract.

Multiple cohort studies and national screening guidelines emphasize that unexplained iron deficiency anemia in adults should trigger evaluation for GI cancer, especially colorectal and gastric malignancies. A 2021 meta-analysis confirmed that among patients over 50 with no obvious source of iron loss, a significant percentage were later found to have gastrointestinal tumors, often discovered through colonoscopy or upper endoscopy.

This has led to widespread clinical protocols recommending full GI workup in adults with persistent microcytic anemia, even when symptoms are absent.

What Science Still Doesn’t Know

While the data behind these lab findings is growing, we’re still in early stages of understanding their mechanistic roles in cancer development. Are these markers just consequences of existing disease, or do they reflect early cellular dysfunction that precedes malignancy?

Research into pre-diagnostic blood markers is ongoing. Much of the cutting-edge work now focuses on:

- ctDNA (circulating tumor DNA)

- Methylation pattern detection

- Proteomics and metabolomics

- Composite biomarker algorithms, combining lab data with AI risk modeling

So far, vitamin levels and traditional CBC metrics haven’t proven precise enough to detect cancer alone. But they may eventually be part of multi-analyte blood tests, where their subtle shifts contribute to a broader risk profile.

In summary, the science supports what experienced clinicians already know: lab abnormalities can be meaningful — but they mean the most when read in context. High RDW, low B12, and microcytic anemia aren’t sirens. They’re quiet alerts — parts of the diagnostic conversation, not conclusions in themselves.

Part Eight: Frequently Asked Questions

Can vitamin B12 deficiency be a sign of cancer?

It can be — but only in specific contexts. Most cases of vitamin B12 deficiency are not caused by cancer. In younger people, it’s usually due to dietary intake, especially in those who avoid animal products, or to conditions that affect absorption like celiac disease or metformin use. But when B12 deficiency appears without a clear explanation, particularly in older adults, it sometimes serves as a clue to underlying gastric problems — including chronic atrophic gastritis or even early stomach cancer. In rarer cases, disruptions in bone marrow function from blood cancers like leukemia or lymphoma can mimic B12 deficiency or interfere with how B12 is used in the body. So while a low B12 level by itself does not mean cancer is present, it can prompt further testing if it persists or occurs alongside other red flags.

Is low potassium a sign of cancer?

Not usually. Low potassium — or hypokalemia — is common in many medical conditions and most often results from medication use, vomiting, diarrhea, or hormonal shifts, not cancer. That said, in patients with known malignancies, persistent low potassium may arise from specific tumor-related effects. Some lung cancers, for example, can trigger hormone-like syndromes that disrupt electrolyte balance. Tumor lysis in leukemia or lymphoma can also cause acute potassium fluctuations. However, for most people, low potassium is more likely to reflect fluid loss or drug effects than any hidden cancer. If it’s persistent, unexplained, or appears with other abnormal labs, your doctor may look deeper, but it is not a typical first clue of malignancy.

Is high RDW a sign of cancer?

High RDW (Red Cell Distribution Width) is not a diagnostic marker for cancer, but it may have prognostic value. RDW reflects variability in the size of your red blood cells, and elevations often occur with iron deficiency, B12 or folate deficiency, or chronic inflammation. In recent years, studies have found that people with cancer — particularly colorectal, lung, and breast cancers — often have higher RDW levels at the time of diagnosis, and that those higher levels are sometimes associated with poorer outcomes. However, high RDW is also seen in completely benign conditions, including common nutrient deficiencies and aging. So while it might raise an eyebrow, especially if paired with other abnormalities, it is not a reliable standalone indicator of cancer.

Is microcytic anemia a sign of cancer?

It can be. Among all the lab findings discussed here, microcytic anemia — especially when caused by iron deficiency — has one of the clearest and best-studied links to cancer, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract. If you’re losing small amounts of blood slowly over time — for example, from an undetected lesion in the colon or stomach — your iron stores may drop, leading to smaller, less functional red blood cells. This pattern can show up in lab work well before any obvious symptoms arise. For that reason, unexplained microcytic anemia in adults, especially those over 50, often leads to a colonoscopy or endoscopy to rule out bleeding from a tumor. While the most common causes of microcytic anemia are not cancerous, it is one of the few lab findings that frequently serves as a first clue in cancer detection — particularly for colorectal cancer.

Closing Thoughts

When something’s off in your bloodwork — a vitamin low, a red cell count off, a pattern that doesn’t quite make sense — it’s natural to wonder how serious it might be. And with cancer always hovering at the edge of that worry, even small shifts can feel like signals.

The truth is that lab abnormalities often come from ordinary causes — diet, age, medications, minor inflammation, or long-standing chronic conditions. But sometimes, in specific patterns or persistent combinations, they reflect deeper disruptions that deserve a closer look. That’s where real medicine happens: not in reacting to a single low number, but in recognizing when a group of quiet changes starts telling a different story.

If there’s one thing to take away, it’s that you don’t have to read your labs in isolation. These numbers aren’t verdicts. They’re pieces of a system — clues that your care team can interpret with experience, context, and perspective. And if something doesn’t sit right — with your results, or your body — asking for answers is never overreacting. It’s the beginning of clarity.