Can Testicular Cancer Cause Low Testosterone?

- Foreword

- 1. Understanding Testicular Cancer

- 2. The Role of Testosterone in Male Health

- 3. How Testicular Cancer Affects Testosterone Levels

- 4. Symptoms and Consequences of Low Testosterone (Hypogonadism)

- 5. Diagnosis and Monitoring of Testosterone Levels

- 6. Treatment Options for Low Testosterone

- 7. Fertility Considerations

- 8. Psychological and Emotional Support

- 9. Long-Term Health Monitoring

- 10. Unique Insights and Lesser-Known Facts

- 11. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

Let’s be honest: if you’re searching for answers about testicular cancer and low testosterone, you’ve probably already tripped over a bunch of clinical jargon, vague reassurance, and maybe a forum post or two that veered off the rails. And still, the big questions remain: Does testicular cancer cause low testosterone? If so, how? What does that mean for the rest of my life? And what are the things nobody really talks about?

The truth is, there’s no single, neat answer — because bodies aren’t that simple, and neither is the impact of cancer or its treatment. But one thing’s for sure: the relationship between testicular cancer and testosterone touches way more than your bloodwork. We’re talking energy, mood, motivation, sex, fertility, identity — all the things that make you you, even if you didn’t pay much attention to hormones before.

That’s why this guide exists. Not to scare, sugarcoat, or offer miracle cures — just to lay everything out, as clearly and honestly as possible. We’ll walk through what testicular cancer actually is, how it might mess with your hormones (sometimes in ways nobody warns you about), what treatment looks like, and the real-life ups and downs that can follow, even years down the road.

If you want a final-stop, nothing-left-out resource — something that treats you like a thinking adult and doesn’t skip the tricky bits — you’re in the right place. Consider this your roadmap, with plenty of room for “Wait, what about…” moments along the way.

Ready? Let’s get into it.

Understanding Testicular Cancer

So, let’s start with the basics — what exactly is testicular cancer?

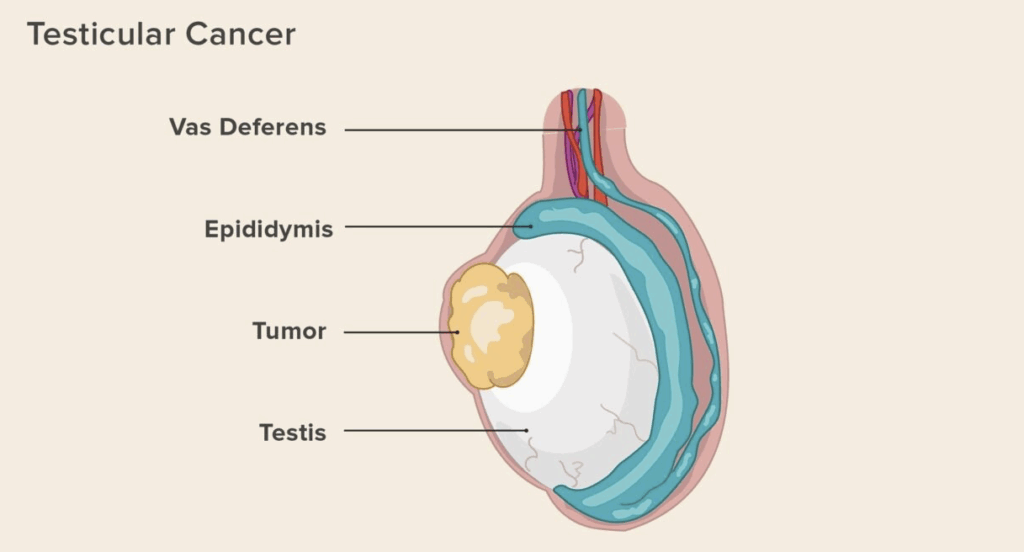

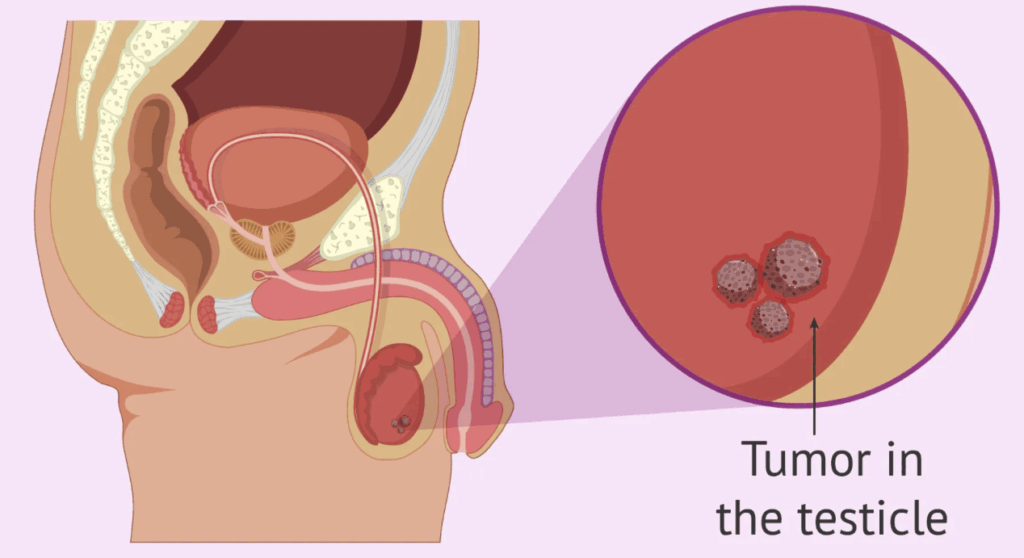

Despite how it sounds, “testicular cancer” isn’t just one thing. It’s an umbrella term for several types of malignant growths that develop in the testicles, the two oval-shaped glands tucked inside the scrotum. These glands do two big jobs: they produce sperm and make testosterone. When cells in the testicles start growing uncontrollably — and ignoring the usual rules about when to stop dividing — that’s when cancer enters the picture.

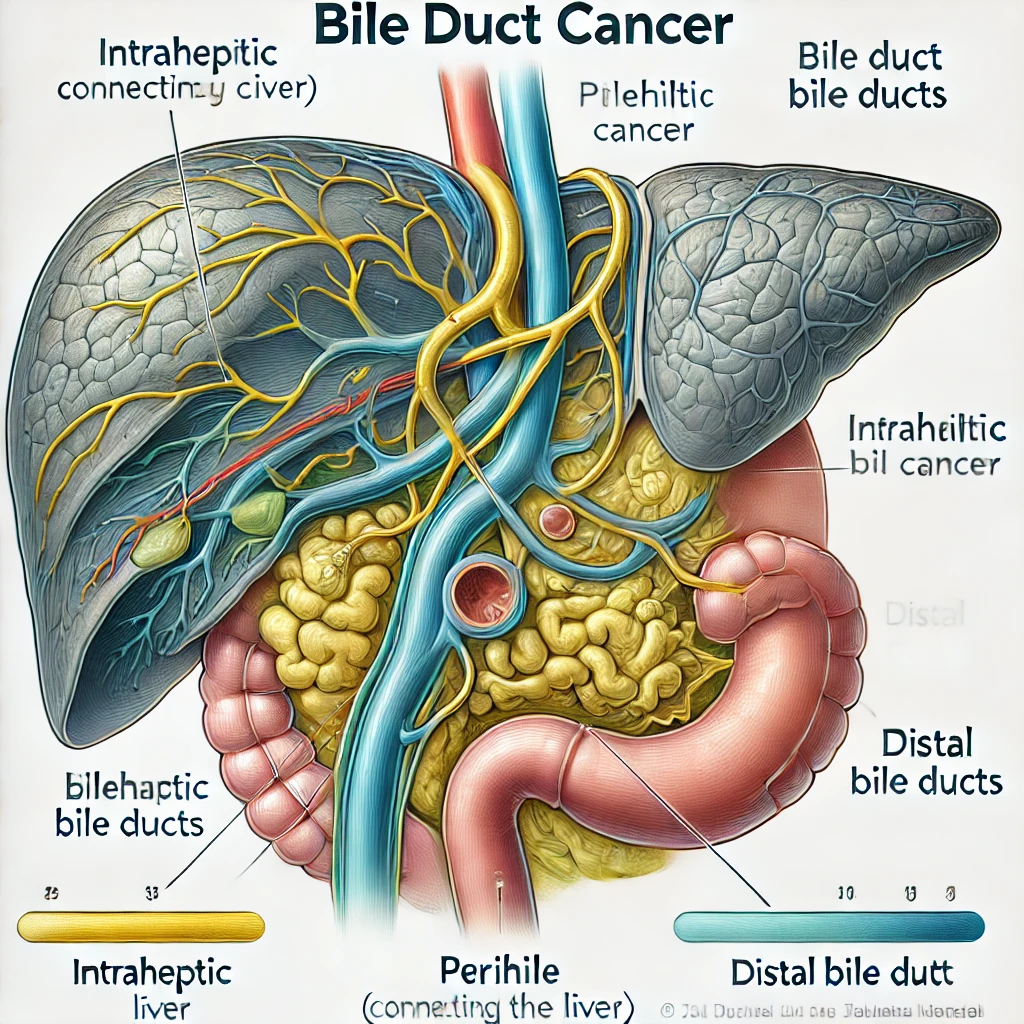

Most cases of testicular cancer fall into two main categories: seminomas and non-seminomas. Both originate in germ cells (the sperm-producing cells), but they behave differently. Seminomas tend to grow more slowly and respond really well to treatment. Non-seminomas, on the other hand, are a bit more diverse and can be more aggressive — though still highly treatable in most cases. The distinction matters when we get into treatment options later, but for now, it’s enough to know that testicular cancer isn’t a one-size-fits-all diagnosis.

Now, here’s a thing that often surprises people: testicular cancer is actually one of the most curable types of cancer — especially when caught early. The five-year survival rate for localized cases? Over 95%. That’s huge. And that high survival rate comes with another side of the coin: a growing population of survivors, many of whom are living with the long-term effects of the disease or its treatment — which brings us straight to today’s central topic: testosterone.

But we’ll get there. For now, let’s stay focused on what this disease is and how it typically shows up.

What causes it?

Good question — and here’s where it gets murky. Like many cancers, we don’t have a single, clear trigger. But we do have some clues. One of the most well-established risk factors is cryptorchidism, which is a fancy way of saying the testicle didn’t descend properly into the scrotum during infancy. Men with a history of this are several times more likely to develop testicular cancer later on.

There’s also a genetic component. If a close relative — say, a brother or father — has had testicular cancer, your risk may go up. But most guys who get it don’t have a family history or obvious risk factor, which makes routine awareness and self-checks important.

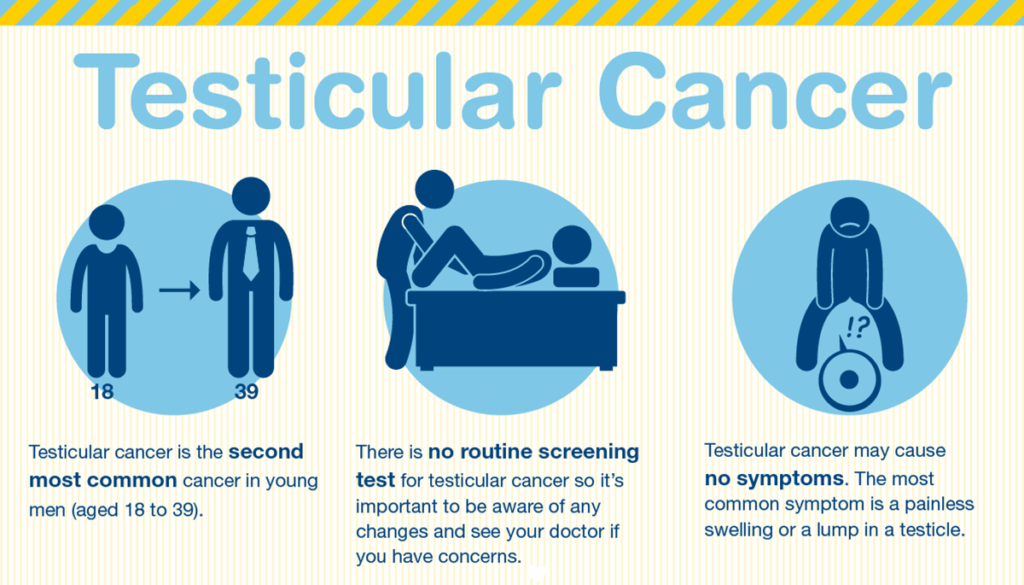

And age? It matters, but not in the way many expect. Testicular cancer isn’t typically a disease of older men. It tends to strike young — most commonly between the ages of 15 and 44. That’s right in the thick of life for a lot of people. School, career-building, relationships, having kids — it all intersects with a diagnosis like this in a way that’s uniquely disruptive.

What does it feel like? How do you know something’s wrong?

If you’re wondering whether you’d know if you had testicular cancer, the answer is… maybe. Sometimes it’s obvious, and other times it sneaks in quietly.

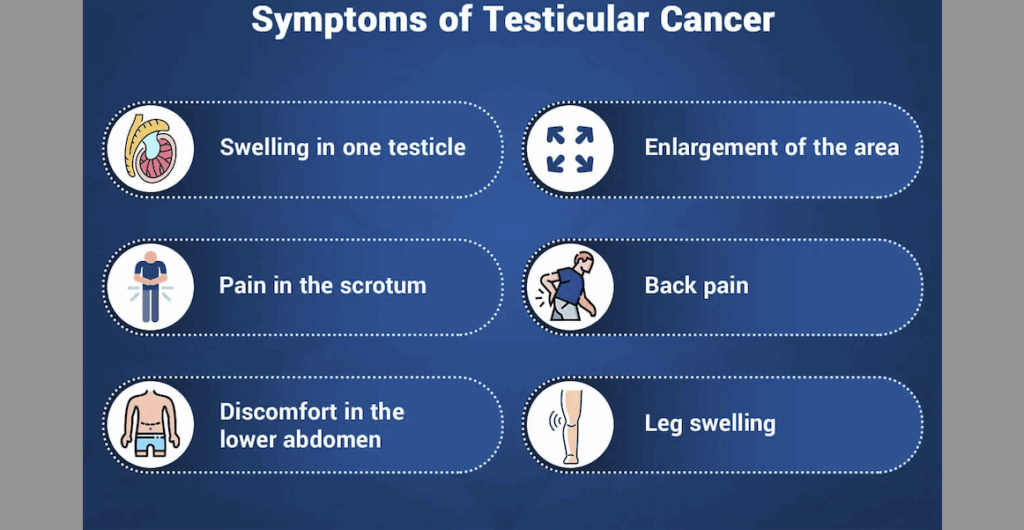

Here are some of the most common signs:

- A painless lump or swelling in one testicle (this is often the first clue).

- A feeling of heaviness or aching in the lower abdomen or scrotum.

- A sudden buildup of fluid in the scrotum.

- Sometimes, changes in how the testicle feels — firmer, different in size, or just off.

Pain isn’t always part of the picture. That’s part of why it can be missed or brushed off for too long. And for anyone wondering — no, testicular cancer doesn’t spread quickly in most cases, but it can if left unchecked. That’s why any persistent or unusual change in the testicles should be brought to a doctor’s attention, even if it feels like a weird or awkward thing to bring up.

How is it diagnosed?

The diagnostic path usually starts with a physical exam, followed by an ultrasound — which, yes, works on testicles just like it does on unborn babies. It’s painless and gives a pretty clear view of whether there’s a mass and what it looks like.

From there, blood tests come into play. Certain proteins — like alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) — can be elevated in men with testicular cancer. These tumor markers help with both diagnosis and monitoring during treatment.

If cancer is suspected, the usual next step is surgery — a procedure called an inguinal orchiectomy, where the affected testicle is removed. It sounds drastic (and yes, it is a big deal), but it’s both diagnostic and therapeutic. They use the tissue to confirm what type of cancer it is, how advanced it might be, and whether further treatment is needed.

That leads us to something people don’t talk about enough: the emotional weight of it all. Losing a testicle — even one — can have a psychological impact, no matter how medically necessary it is. It’s not just about fertility or hormones (though those matter). It’s also about identity, self-image, confidence. And this, too, feeds into the conversation about testosterone, which we’re about to unpack in the next section.

One of the key follow-up concerns after testicular cancer is hormonal balance, and this connects closely with topics like Prostate Cancer and VA Ratings, which also involve endocrine implications.

So yeah — testicular cancer is highly treatable, but it’s not a “small” cancer just because the stats are good. The ripple effects, physically and emotionally, are real. And that includes what it can mean for hormone levels in the weeks, months, and years that follow.

The Role of Testosterone in Male Health

Okay, so testosterone. You’ve heard of it, probably associate it with masculinity, muscles, maybe even mood swings — but how well do most of us really understand what it is or what it does? Let’s break it down.

At its core, testosterone is a hormone. More specifically, it’s an androgen, which means it’s responsible for developing and maintaining male characteristics. It’s produced primarily in the testicles, though the adrenal glands (those little triangular organs that sit on top of your kidneys) make a small amount too. That might sound like a technical detail, but it becomes incredibly relevant when one testicle is removed or damaged — suddenly, your testosterone factory is working at half-capacity, or maybe even less, depending on other factors.

So, what does testosterone actually do?

Well, a better question might be: what doesn’t it do?

Most people think of it as the hormone that kicks in during puberty — deepening the voice, building muscle, prompting those first forays into sexual desire. And sure, it does all of that. But its role doesn’t stop there. In adult men, testosterone remains a key regulator of:

- Muscle mass and strength

- Fat distribution

- Bone density

- Red blood cell production

- Sex drive and fertility

- Mood, energy, and cognitive function

That’s a lot riding on one hormone. So when levels drop — due to illness, injury, treatment, or age — the effects can cascade in ways that are both physical and emotional.

But here’s a common question: If you’ve still got one testicle, won’t it just pick up the slack?

Sometimes, yes. The human body is often remarkably good at compensating. One healthy testicle can produce enough testosterone to keep things more or less within the normal range. But — and it’s a big but — not everyone bounces back that smoothly. The remaining testicle might already be compromised. Or maybe chemotherapy has affected the delicate hormonal feedback system that governs testosterone production. Or perhaps it’s just age working against you.

What’s often misunderstood is that testosterone production isn’t a simple on/off switch. It’s regulated by a feedback loop involving the brain — specifically, the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. If that system gets disrupted (and cancer treatment can absolutely disrupt it), testosterone output can drop even if the remaining testicle is intact. This is where things get nuanced and why broad assumptions like “you’ve still got one, so you’ll be fine” don’t always hold up in reality.

Let’s take a quick detour here, because it’s worth asking: What’s considered a “normal” testosterone level anyway?

This trips up even some clinicians. In most adult men, a typical total testosterone level sits somewhere between 300 to 1,000 ng/dL (nanograms per deciliter). That’s a huge range. And not everyone feels good at the same point within it. You could technically be in the “normal” range but still experience symptoms of low testosterone — a frustrating reality for many men who are dismissed because their numbers aren’t “low enough” to warrant treatment.

And yes, symptoms matter — we’ll dive into those more deeply in the next section, but it’s worth planting the idea here that testosterone isn’t just a lab value. It’s about how your body feels and functions. If libido has tanked, energy’s gone, mood’s erratic, and muscle strength is fading, the numbers on paper are only part of the puzzle.

Another thing to consider: testosterone levels naturally decline with age, usually beginning around 30. So for a guy in his 40s or 50s recovering from testicular cancer, there may be a sort of double hit — age-related decline plus cancer-related disruption. And that combo can have a more noticeable effect than either would on its own.

To sum up this section, here’s what we’re working with:

- Testosterone is essential — not just for sex and muscles, but for overall physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

- It’s made mainly in the testicles, with production governed by a complex brain-to-gland feedback system.

- Losing a testicle doesn’t guarantee low testosterone, but it absolutely increases the risk — especially when combined with other factors like chemo or radiation.

- And finally, “normal levels” aren’t a one-size-fits-all situation — how you feel is as important as what your labs say.

So, when we ask whether testicular cancer can cause low testosterone, it’s not just a yes-or-no deal. It’s about understanding all the ways cancer — and its treatments — can knock this critical hormone off balance. That’s where we’re headed next: how exactly testicular cancer messes with testosterone production, and why the aftermath can look so different from one survivor to the next.

How Testicular Cancer Affects Testosterone Levels

Let’s get to the heart of it: can testicular cancer cause low testosterone? Yes — it can. But the more useful question is how and why that happens. Because the answer isn’t always straightforward, and it certainly isn’t the same for every guy who walks this path.

Start with the obvious: testosterone is made in the testicles. So if a tumor is growing inside one — or if one or both testicles are surgically removed as part of treatment — there’s a pretty clear potential for disruption. But the devil’s in the details, and it turns out those details matter a lot.

So, does the cancer itself kill off testosterone?

Sometimes, yes — at least partly. If the tumor damages the part of the testicle responsible for hormone production (mainly the Leydig cells), then testosterone output can dip even before any treatment begins. That said, the bigger hormonal hit usually comes from the treatment, not the cancer alone. For a lot of men, their testosterone levels don’t nosedive the moment they’re diagnosed — they drop after surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or some combination of the three.

Let’s take those one at a time.

First, surgery — the orchiectomy

Most men diagnosed with testicular cancer undergo something called an inguinal orchiectomy. It sounds complex, but in practice, it’s the surgical removal of the affected testicle through an incision in the groin. It’s the standard approach for both diagnosing and treating localized tumors.

Now, here’s where things get nuanced. If you lose one testicle, the remaining one can often keep testosterone levels within the normal range. The body has a pretty decent reserve capacity, and many men never notice a difference. But — and this is crucial — not everyone’s remaining testicle is a model of perfect function. Some guys may have subtle, undiagnosed issues with the second testicle. Others may have already been on the low end of the testosterone spectrum to begin with. In those cases, even losing just one can be enough to tip the scales.

Then there’s the less common, but very real, scenario where both testicles need to be removed. This is called a bilateral orchiectomy, and in that case, testosterone production ceases almost entirely. Men in this situation will require lifelong hormone replacement therapy — not because it’s optional, but because testosterone is essential for more than just sex and muscles. Without it, the body simply doesn’t function properly.

Next: chemotherapy and radiation

These treatments are incredibly effective at destroying cancer cells. Unfortunately, they can also be rough on healthy tissue — including the Leydig cells in your testicles and, as mentioned earlier, the brain-based hormonal feedback loop that controls them.

Chemo, particularly with drugs like cisplatin (a common player in testicular cancer treatment), can lower testosterone levels by damaging hormone-producing cells directly. The effect isn’t always permanent — some men bounce back within a year or two — but for others, the damage lingers. The same goes for radiation, which is typically used less often for non-seminomas but is still in the toolkit for certain seminomas. Radiation doesn’t just zap cancer cells; it can also impact nearby healthy cells and disrupt hormone signaling over time.

So again, the answer isn’t always “yes” or “no” — it’s “maybe, and it depends.”

But what do the numbers say?

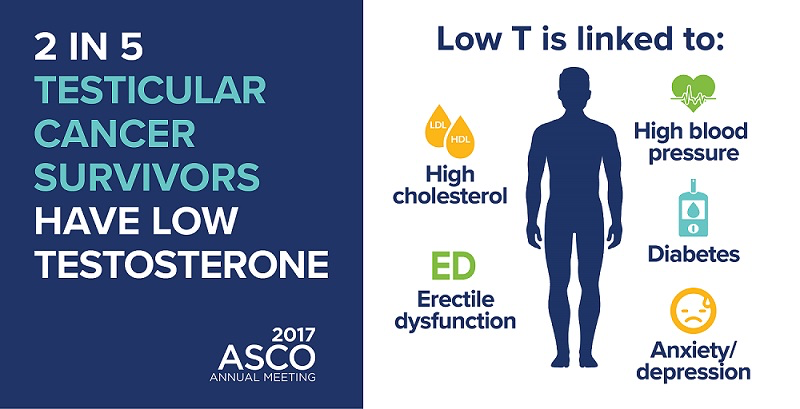

Glad you asked. Several studies have tried to pin this down. One notable piece of research from Indiana University found that about 38% of testicular cancer survivors ended up with clinically low testosterone levels. That’s a significant chunk — more than one in three. And these weren’t just older men or people with multiple health issues. These were otherwise healthy guys, many of them under 40.

Another study looked at the longer-term picture and found that even when testosterone levels stayed within the “normal” lab range, a lot of men still reported classic symptoms of deficiency — fatigue, low libido, irritability, poor concentration. In other words, lab values alone don’t always tell the full story.

Which brings up a critical point: a lot of men aren’t routinely checked for testosterone after treatment. If you’re not reporting symptoms, it may not even come up. And even if you are reporting symptoms, they’re often chalked up to stress, aging, or “adjusting” after cancer — which can delay proper diagnosis and treatment.

So, who’s most at risk?

Men who’ve had both testicles removed are at the top of the list — no surprise there. But even among men who’ve kept one testicle, risk rises if:

- They received chemotherapy or radiation.

- They had testicular dysfunction or borderline hormone levels before diagnosis.

- They were already in an age bracket where testosterone naturally begins to decline (i.e., 35+).

- Their symptoms are overlooked, misinterpreted, or minimized — by themselves or their providers.

And remember, low testosterone isn’t just about libido or mood. It has real implications for long-term health — bone density, cardiovascular function, metabolism, even insulin sensitivity. Which is why this isn’t just about “feeling off.” It’s about your whole system potentially running on less fuel than it needs.

So where does this leave us?

It leaves us with a very real, medically recognized link between testicular cancer and low testosterone — one that’s complicated by treatment type, age, preexisting conditions, and how closely someone is monitored afterward. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s common enough that no testicular cancer survivor should be left wondering why they feel tired, down, weak, or disinterested in things they used to enjoy.

If you’re wondering what symptoms to monitor beyond testosterone drops, Warning Signs of Cancer Head to Toeoffers a broader diagnostic lens.

In the next section, we’ll explore exactly what low testosterone feels like — how it shows up in day-to-day life, what the red flags are, and why so many men don’t realize it’s happening until they’re already deep in the fog.

Symptoms and Consequences of Low Testosterone (Hypogonadism)

Let’s say you’ve gone through treatment for testicular cancer — surgery, maybe some chemo, maybe not. Months go by, maybe years. Life slowly picks up again. But something feels… off.

Not catastrophic. Just… off.

You’re more tired than usual, but maybe you chalk it up to stress or aging. You’ve lost interest in sex, but that could just be “normal” post-treatment stuff, right? Your workouts aren’t hitting the same, the weight’s creeping up, and your mood’s weirdly flat. Nothing specific, but enough that your old self feels like a version in the rearview mirror.

Could it be low testosterone?

Absolutely — and this is where things start to click for a lot of men. Because hypogonadism (the fancy term for low testosterone) often creeps in slowly and wears a bunch of different disguises. It’s not just a sexual health issue, though that’s the symptom that gets the most attention. It can affect everything from your mental clarity to your bone health — and it’s shockingly underdiagnosed.

Let’s unpack the symptoms first. Not in a checkbox kind of way, but in terms of how they feel in real life.

Fatigue that isn’t fixed by sleep

We’re not talking about being tired after a late night. This is the kind of fatigue that lingers — the heavy-limbed, brain-fog kind of exhaustion that makes mornings harder and afternoons sluggish. It’s not dramatic, but it’s persistent. And for a lot of men, it’s the first domino.

Libido dips (and not just about sex)

Yes, testosterone drives sexual desire. But it also plays a quiet role in motivation and engagement with the world in general. Low libido often comes with a side order of emotional flatness. It’s not always “I don’t want sex” — sometimes it’s “I don’t want anything.”

Muscle changes, slow recovery, unexpected softness

You might notice workouts aren’t giving the same payoff. Or you feel sore longer. Or you’re just not as strong as you used to be. Testosterone is anabolic — it helps build muscle and keep fat in check. When it drops, things change. Not overnight, but noticeably.

Emotional shifts: irritability, depression, anxiety

Men don’t always connect mood swings or low-grade depression to hormones. But testosterone affects serotonin and dopamine pathways — the same ones that antidepressants target. So if your fuse is shorter or your general mood is grayer, this isn’t “just in your head.” It’s also in your bloodwork.

Brain fog and cognitive sluggishness

Hard to focus? Forgetful? Struggling to find words or keep up in conversations? Low testosterone can make your brain feel like it’s stuck in second gear. It doesn’t mean you’re losing IQ points — just that your mental sharpness isn’t firing on all cylinders.

The physical consequences no one talks about enough

Let’s step back from the day-to-day for a second and look at the longer game. Chronic low testosterone can increase your risk for:

- Osteoporosis – Yes, it’s not just a “women’s issue.” Men with low T are at greater risk for weak, brittle bones.

- Cardiovascular disease – There’s growing evidence linking low testosterone to poor heart health, including increased cholesterol and arterial stiffness.

- Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance – Low testosterone is associated with higher rates of abdominal fat, blood sugar issues, and even type 2 diabetes.

Now imagine all of that sneaking in quietly after cancer treatment, while you’re still adjusting to the emotional and physical fallout. You’re supposed to feel “grateful” to be in remission — and of course you are — but it doesn’t mean you’re thriving. And thriving is the bar we should be aiming for, not just surviving.

So, here’s the critical takeaway: If you’re noticing these changes, they’re worth investigating. You don’t need to wait until they “get worse” or become unbearable. If you’ve had testicular cancer, you’re already in a higher-risk group for testosterone deficiency. That means vigilance isn’t paranoia — it’s prevention.

And just to underline the frustrating truth one more time: low testosterone doesn’t always scream. Sometimes it just whispers. It’s that quiet undercurrent of “not feeling right” that gradually becomes the new normal — until someone finally runs the labs and the numbers confirm what your body’s been saying for months or years.

Coming up: how to test for low testosterone, when to do it, and what those test results actually mean (and don’t mean). Because getting the numbers is one thing — understanding them is a whole different story.

Diagnosis and Monitoring of Testosterone Levels

So you’ve got the suspicion — maybe based on how you’re feeling, maybe based on your history. What now? How do you actually know if your testosterone is low?

The good news is, this isn’t guesswork. It’s testable. But (and here’s the frustrating twist), testing isn’t always done well — or at the right time — or interpreted in a way that reflects what’s actually going on in your body. So let’s go step-by-step and clear the fog.

First off: when should you get tested?

If you’re a testicular cancer survivor and you’re experiencing any of the symptoms we talked about earlier — fatigue, low libido, emotional dullness, muscle loss, sleep issues, the works — you have more than enough reason to get your levels checked. Even if you’re not experiencing symptoms but you had bilateral orchiectomy, or you went through chemotherapy or radiation, it’s worth doing routine monitoring. Not once, but at regular intervals post-treatment — think annually at the very least.

You don’t need to wait for things to feel “bad enough.” You can be proactive. Testosterone is like blood pressure or cholesterol: you monitor it so you can respond early, not just scramble when things fall apart.

And how’s it tested?

It’s a blood test — simple enough in theory. But there’s a timing element people often miss: Testosterone should be measured in the early morning, ideally between 7 a.m. and 10 a.m. That’s when levels are naturally at their peak, and testing at other times can give falsely low readings.

What you’re typically measuring is total testosterone — which, as the name suggests, is the overall amount floating around in your bloodstream. But here’s the thing: not all of that testosterone is “available” for use. Most of it is bound up by proteins like SHBG (sex hormone-binding globulin), which makes it biologically inactive.

That’s why in some cases — especially when symptoms are present but total T looks “normal” — doctors will dig deeper and check free testosterone or bioavailable testosterone. Those give a clearer sense of what your body can actually use.

Here’s where the confusion often sets in: what counts as “low”?

- In general, most labs use 300 ng/dL as the lower threshold for total testosterone in adult men.

- But some men can have symptoms at 350 or 400. Others might feel fine at 280.

- And free testosterone? That has its own reference range, usually in picograms per milliliter (pg/mL) — and again, symptoms don’t always perfectly match the numbers.

So no, you’re not crazy if you feel awful but your test results say “normal.” That mismatch happens all the time. And it’s why good doctors look at both labs and clinical presentation — not just one or the other.

How often should testosterone be checked?

This depends on a few factors:

- If your levels are borderline or symptoms are fluctuating, you might re-test in 3–6 months.

- If you’re undergoing treatment (like testosterone replacement therapy), your doctor will likely monitor levels every few months to start, then taper off to once or twice a year.

- If you’re stable, asymptomatic, and not on therapy, once a year is often enough — just to keep tabs on the trend.

And don’t forget to look beyond testosterone alone. If you’re feeling off, a more complete hormone panel might be useful — things like LH (luteinizing hormone), FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone), estradiol, and SHBG can all give context to the T levels you’re seeing. It’s the hormonal ecosystem, not just a single number.

Here’s a scenario to consider:

Let’s say a man who had one testicle removed five years ago during early-stage cancer treatment comes in with low energy, poor sleep, and waning libido. His testosterone is measured at 325 ng/dL — technically “normal.” But his free testosterone is scraping the bottom. His LH is elevated, which suggests his body is trying to stimulate more T production but the testicle isn’t responding well.

That’s a classic case of compensated hypogonadism. His brain knows he needs more T, but his single testicle isn’t keeping up. Is it “low T” by the book? Not quite. But by symptoms and lived experience? Absolutely. And that’s where therapy or intervention might come into play — not based on a number alone, but on the full picture.

So, what’s the real takeaway here?

It’s that testing for low testosterone is simple, but interpreting it? That’s an art as much as a science. It’s about context. It’s about patterns. And most of all, it’s about listening — to the numbers, yes, but also to the body and the story it’s telling.

In the next section, we’ll dive into what to do if you’ve been diagnosed with low testosterone — covering everything from testosterone replacement therapy to alternative strategies, and the real-world pros and cons of each.

Treatment Options for Low Testosterone

So let’s say you’ve had your levels checked. Maybe more than once, just to be sure. Symptoms line up. Bloodwork backs it. Your doctor confirms it: your testosterone is low.

What now?

This is the fork in the road where things get both hopeful and complicated. The hopeful part? There are multiple treatment options, and many men respond incredibly well to the right one. The complicated part? Not all treatments are created equal, and choosing the right path depends on your goals, your medical history, and — critically — whether fertility still matters to you.

Let’s start with what most people think of when they hear “low T treatment” — testosterone replacement therapy, or TRT.

TRT: Straightforward in concept, nuanced in practice

The idea behind TRT is simple: if your body isn’t making enough testosterone, give it some from the outside. This can be done in a few ways — each with its own rhythm, cost, and quirks:

- Injections (testosterone cypionate or enanthate) — usually done every 1–2 weeks, these are the most common and cost-effective option, but can lead to hormonal peaks and troughs if not managed well.

- Gels and creams — applied daily to the skin, often preferred for their steady levels, but they’re more expensive and can transfer to others through skin contact.

- Patches — stick them on daily; same benefits and drawbacks as gels, but some people get skin irritation.

- Pellets — tiny implants placed under the skin every few months. Low maintenance, but require a procedure and don’t allow easy dose adjustment.

- Nasal gel — yep, it exists. Multiple daily doses, less popular, but an option.

TRT often works. Libido returns. Energy lifts. Mood improves. For many men, it feels like flipping the lights back on.

But — and this is a big but — TRT also suppresses sperm production. Because when you flood the body with testosterone, it signals the brain to shut down its own production, including the hormones (LH and FSH) that stimulate the testicles to make sperm. So if you’re hoping to have biological children in the future, you really need to think this through before starting TRT. Once you’re on it, restoring fertility can take months — or longer.

Which leads us to…

Alternative therapies: For men who want to preserve fertility

If fertility is still on the table — whether now or someday — your doctor might suggest options that stimulate your own testosterone production instead of replacing it.

Two of the big ones:

- Clomiphene citrate (Clomid) – Originally used to treat female infertility, this medication can “trick” your brain into producing more LH and FSH, which in turn stimulates the testicles to make more testosterone and sperm. It’s oral, relatively low-risk, and surprisingly effective for many men.

- Enclomiphene – A more refined, targeted version of clomiphene that skips the estrogenic side effects Clomid can sometimes produce. Still relatively new, but promising.

These aren’t perfect — not everyone responds, and results can take a while — but for younger men or anyone with even a remote interest in fatherhood, they’re a serious consideration.

Supplements, herbs, and “natural boosters” — worth it?

You’ve probably seen these online. Testosterone boosters promising to “ignite your manhood” or “crank up your T like you’re 18 again.” Most of them are nonsense. Some might nudge levels a little if you’re borderline — especially if they address a deficiency like zinc or vitamin D — but none of them are a substitute for medical treatment if your levels are clinically low.

That said, lifestyle changes do matter — not as a standalone cure, but as a foundational support:

- Getting enough sleep (testosterone is made during deep sleep).

- Resistance training (especially compound lifts like squats and deadlifts).

- Managing stress (chronic cortisol crushes testosterone).

- Cutting excessive alcohol and processed foods.

- Losing excess belly fat (adipose tissue converts testosterone into estrogen).

No, this stuff won’t “fix” severe hypogonadism on its own. But if you’re in that borderline space — or looking to support TRT — it absolutely has a role.

Are there risks to TRT?

Yes — no treatment is without trade-offs. Possible risks include:

- Increased red blood cell count (can lead to thickened blood).

- Worsening of untreated sleep apnea.

- Acne or oily skin.

- Breast tenderness or enlargement.

- Suppression of natural hormone production and fertility.

- And in men with prostate issues, there’s long-standing (though somewhat debated) concern about stimulating growth in dormant prostate cancer cells.

That’s why TRT should always be done under medical supervision, with regular blood work to monitor testosterone, hematocrit, PSA, and other relevant markers. Self-medicating with black market testosterone? Genuinely dangerous. The risk-reward ratio goes straight out the window.

So how do you decide?

This part is personal. For some, the relief and energy TRT brings is life-changing and worth every injection or patch. For others — especially younger survivors, or those hoping to start a family — a slower, fertility-friendly route makes more sense.

The key is informed choice. Not pressure, not panic, not Dr. Google. You want a clinician who understands not just testosterone levels but the broader picture — testicular cancer history, fertility, emotional wellbeing, and your actual goals.

And whatever path you choose? Regular follow-up is non-negotiable. Hormones change over time. What works now may need to be tweaked a year from now. This isn’t a one-and-done situation — it’s an ongoing process of tuning and re-tuning.

And for anyone dealing with fertility or identity-related shifts, Refusing Hormone Therapy for Breast Cancer shows how hormone-linked choices impact more than just lab numbers.

Next, we’ll talk about fertility directly — what testicular cancer and its treatments can do to reproductive health, and how testosterone therapy fits into (or clashes with) that whole equation.

Fertility Considerations

Let’s not tiptoe around this: fertility is one of the most emotionally loaded, quietly terrifying parts of dealing with testicular cancer. And yet, it’s often the least talked about.

For a lot of men — especially younger ones — questions around having kids someday are hazy, abstract, maybe even on the back burner entirely. Until suddenly, a diagnosis lands, and treatment starts moving fast. Surgery is scheduled. Chemo’s on the table. Hormone levels might tank. And fertility? It becomes a question that’s either uncomfortably hypothetical or uncomfortably real — sometimes both at once.

So let’s unpack it.

Does testicular cancer affect fertility?

It can, yes. Even before treatment. Some studies suggest that testicular cancer itself — particularly when it impacts the health of the remaining testicle — can reduce sperm quality or count. The exact mechanisms aren’t totally clear, but the link’s been observed enough to take seriously.

Then, of course, there’s treatment. If you’ve had one testicle removed, your body can often adapt and keep producing viable sperm — especially if the other testicle is healthy. But if the remaining one is underperforming, or if it later gets hit with radiation or chemotherapy, sperm production can drop — sometimes sharply, sometimes permanently.

Chemo’s the big one here. Cisplatin-based regimens (which are very common in testicular cancer treatment) are known to be gonadotoxic, which is just a polite way of saying they can mess with your sperm production. Some guys bounce back within a year or two. Others don’t.

And then there’s the less common scenario of bilateral orchiectomy — removal of both testicles. This obviously ends natural testosterone and sperm production, making biological fatherhood impossible without prior sperm banking.

So the key takeaway? Fertility should be part of the conversation before treatment starts. Always. Even if you’re unsure about kids. Even if you’re certain you don’t want them now. Because it’s not about today’s decision — it’s about preserving the option for tomorrow.

What about sperm banking?

It’s the single most effective, widely recommended way to safeguard fertility before cancer treatment. And yet — and this is frustrating — a lot of men aren’t clearly informed about it in time.

Sperm banking (or cryopreservation, if you want the clinical term) involves producing one or more semen samples, which are then frozen and stored for future use in assisted reproduction. It’s not complicated. It’s not invasive. It’s not prohibitively expensive, especially compared to the long-term cost of infertility treatment if you don’t do it.

Even if your sperm count is already a little low — which can happen in men with testicular cancer — freezing what you can before treatment begins is still the safest move.

Now, let’s say you’ve already had treatment and didn’t bank sperm beforehand. What then?

Can fertility come back?

Sometimes, yes. It depends on the type and intensity of treatment, your age, your baseline testicular function, and — frankly — a bit of luck. Some men recover sperm production within months. Others take years. And some don’t at all.

That’s why semen analysis (a simple test to check sperm count, motility, and morphology) is a good idea after treatment, especially if family planning is on your radar. And even if fertility doesn’t return naturally, options like IVF or sperm retrieval procedures exist — though they’re more involved and can get expensive fast.

How does TRT affect fertility?

This is where things get tricky. Remember in the last section we said testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) can shut down sperm production? That’s not a side effect — it’s a built-in mechanism. When your body gets testosterone from outside sources, it stops producing the hormones (LH and FSH) needed to stimulate your testicles. The result? Your testes essentially go dormant. They shrink. Sperm production halts.

For some men, this effect is reversible after stopping TRT — but not always, and not quickly. We’re talking months or even years, and in some cases, it doesn’t bounce back fully. That’s why TRT should be a carefully considered decision, not just something you start because you’re tired and your T is a little low.

If preserving fertility is a goal — even a maybe-one-day goal — alternatives like clomiphene citrate or hCG are usually preferred. These meds stimulate your body to make its own testosterone and keep sperm production going. They’re slower-acting, but fertility-friendly.

What if you’re done having kids?

Then the calculus changes. If fertility is no longer a concern — say you’ve had a vasectomy, or you’ve already had kids and aren’t planning more — then TRT becomes a more viable and straightforward option. The risk of fertility loss becomes irrelevant, and treatment can be focused entirely on symptom relief and quality of life.

But you still need to monitor things closely. TRT isn’t plug-and-play. Hormones are interlinked systems, not isolated dials you just turn up or down. You’re not just tweaking testosterone — you’re influencing red blood cell production, estrogen balance, even mood stability and heart health.

So where does that leave you?

It leaves you, hopefully, better informed. Fertility is personal. It’s emotional. It’s logistical. And it deserves a front-row seat in any discussion about testicular cancer and testosterone — not as an afterthought, but as a central part of the bigger picture.

In the next section, we’ll move into the psychological landscape — the stuff that doesn’t always make it onto lab reports but affects everything: identity, masculinity, mood, relationships. Because hormones are one thing. But feeling like yourself again? That’s a whole different story.

Psychological and Emotional Support

Let’s get real for a second. If you’ve had testicular cancer — or you’re dealing with low testosterone after treatment — the hardest part isn’t always the surgery, or the chemo, or even the hormone crash.

Sometimes, it’s the quiet stuff that follows.

The self-doubt. The loss of identity. The unspoken fear that you’re somehow not fully you anymore — or not the version of you you used to be. That emotional territory? It’s messy. And it’s rarely talked about with the same openness as the physical side of recovery.

But it should be. Because hormones don’t just govern muscles and libido — they touch everything. Confidence. Energy. Memory. Mood. Even that vague, hard-to-pin-down feeling of being okay in your own skin.

What happens emotionally when testosterone drops?

Testosterone isn’t a personality hormone, but it plays a role in how assertive, resilient, and motivated you might feel. So when it drops — either gradually or after a sudden hit from cancer treatment — the psychological impact can be subtle at first, then oddly disorienting.

Men often describe it like this: I just don’t feel like myself. That’s not about ego or vanity — it’s about internal balance. That feeling can show up as persistent irritability, or a flat, depressive mood that doesn’t respond to the usual fixes like rest, exercise, or social time. Some lose interest in hobbies or stop initiating intimacy, not because they don’t care, but because the physiological drive has gone quiet.

And let’s not overlook anxiety. When testosterone dips, cortisol (the stress hormone) can rise. That hormonal mismatch creates a kind of internal friction — jittery, restless, unable to settle. You’re tired and wired. Frustrated, but also emotionally numb. It’s a weird loop. You know something’s wrong, but you can’t put your finger on what exactly, or why you can’t shake it.

Then there’s the masculinity piece

Let’s not pretend this isn’t a thing. Losing a testicle — even if your health outcome is good — can have a profound emotional effect. Not because masculinity is defined by body parts (it’s not), but because identity is such a personal and often unexamined structure. You don’t realize how much you’ve internalized certain ideas about your body, your virility, your role in the world — until something changes.

For some, there’s shame — even if it’s totally unspoken. For others, it’s fear: will I still be attractive? Will sex feel the same? Will I ever fully want again?

These are real questions. They don’t always get answers. But acknowledging them — talking about them — is a first step out of the fog.

Support often feels optional. It isn’t.

Here’s the honest truth: many men don’t seek psychological support because they think they “should” be okay. Especially if the cancer’s been cured. Especially if people around them are saying, “You’re so lucky — it was caught early,” or “At least it wasn’t worse.”

And sure, gratitude is important. But so is grief. So is processing loss — of certainty, of control, of how you used to feel in your own body. That stuff doesn’t go away because you survived. Sometimes it only starts showing up once the crisis has passed.

This is where professional mental health support can make a massive difference. Not in a “you’re broken and need fixing” kind of way, but as a guided space to untangle what’s going on beneath the surface. Therapy isn’t about making the feelings go away — it’s about making them less isolating, more manageable, more understood.

Group settings — especially cancer-specific or men’s health groups — can also be powerful. There’s something uniquely settling about being in a room (even virtually) with people who get it without needing every detail explained. It doesn’t fix things. But it can remind you that you’re not weird, weak, or alone.

And if you’re supporting someone through this?

Listen more than you fix. That might sound overly simple, but it matters. It’s tempting to jump in with reassurance: “You’re fine,” “You’ll bounce back,” “It’s just hormones.” And while those come from love, they often miss the mark. What’s often needed is just space — for the fear, the frustration, the “I don’t know how to feel about this” stuff to be voiced without judgment.

So where does all this land?

It lands in a place of permission — to take your emotional and mental health as seriously as you’ve taken the physical. Not as an afterthought. Not as “bonus work.” But as an integrated part of real, whole-person recovery.

And the point isn’t to pathologize every bad mood or anxious thought. It’s to normalize the truth that recovering from testicular cancer — especially when hormones get involved — is a full-body, full-brain process. You don’t just go back to how you were before. You go forward, changed — and hopefully, supported.

Long-Term Health Monitoring

So you’ve been through the storm. The cancer’s gone. Maybe you’ve had a testicle removed. Maybe you’ve had chemo. Maybe you’re on testosterone therapy now, or maybe you’re still sorting that part out. Either way — you’re in the “after” now.

But here’s the thing no one really tells you about the “after”: it’s not static. You don’t just finish treatment and land in some stable, unchanging place where everything stays fixed. The body keeps evolving. Hormone levels shift. Energy levels come and go. Recovery isn’t a line — it’s a spiral. And that means ongoing monitoring isn’t optional. It’s part of the deal.

Why keep testing if you “feel fine”?

This is a common question — and a fair one. If your mood’s good, your sex drive’s decent, and your labs were solid six months ago… why keep checking?

Because hormone levels can drift slowly, without obvious symptoms. The body is adaptable — sometimes too adaptable. You might not notice subtle declines in testosterone or increases in estradiol (a form of estrogen) until they’ve been going on for months. And by then, you’re not catching it early. You’re playing catch-up.

The same goes if you’re on testosterone therapy. Just because your symptoms improved doesn’t mean everything under the hood is running smoothly. TRT can impact other systems — like red blood cell count (too high and you’re at risk for clots), or PSA levels (a marker for prostate health), or liver enzymes. That’s why follow-up testing isn’t some annoying box to tick — it’s how you stay ahead of potential complications.

What should be monitored long term?

Let’s zoom out and look at the full picture — not just testosterone, but the web of other health indicators that can be influenced by cancer, hormone loss, and treatment:

- Testosterone levels – both total and free, ideally tested in the morning. If you’re on TRT, this confirms you’re staying in the therapeutic range.

- LH and FSH – useful if you’re not on TRT, to see whether your body is trying (and failing) to make testosterone naturally.

- Estradiol – because too much T can convert to estrogen, especially if you’re overweight or using higher doses of TRT.

- Hematocrit and hemoglobin – TRT can stimulate red blood cell production, which is good up to a point — but too much can raise your risk of blood clots or stroke.

- PSA (Prostate-Specific Antigen) – especially if you’re over 40 or have any family history of prostate issues.

- Bone density – low testosterone increases the risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis. If you’ve had consistently low T or a long stretch without treatment, a DEXA scan might be a good idea.

- Lipid panel and glucose – metabolic health matters here. Low testosterone and some TRT protocols can impact cholesterol and insulin sensitivity.

Okay, but how often is “ongoing”?

That depends. In the first year after treatment — especially if you’re starting TRT or trying alternative therapies like clomiphene — bloodwork every 3–6 months is typical. Once things are stable, many clinicians shift to annualmonitoring, unless symptoms return.

But monitoring isn’t just about lab results. It’s also about paying attention to how you feel. If you’ve been feeling sharper, stronger, more emotionally steady — then you dip back into fatigue or lose interest in sex or find yourself strangely irritable for no clear reason — that’s your cue. Even if it’s subtle. Even if it feels “not worth bothering your doctor about.” Because often, those are the early signs that something’s shifted.

What about bone and heart health — are those really a thing?

Yes. Seriously — they are.

Testosterone plays a quiet but critical role in both bone and cardiovascular health. Low testosterone is linked to reduced bone density, which increases the risk of fractures as you age — especially in the hips and spine. It’s not just a concern for “old guys.” Long-term hypogonadism, untreated, can absolutely put you at risk in your 40s and 50s.

As for your heart — the science is still evolving, but we know this much: men with consistently low testosterone tend to have higher rates of metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and poor cholesterol profiles. That’s not nothing. And while TRT isn’t automatically protective (and in some cases may slightly raise risk depending on other factors), managing testosterone levels thoughtfully is part of broader cardiovascular health.

So if you’re thinking long game — like, “How do I stay strong, energetic, and independent into my 60s and 70s?” — this stuff matters. And your 30s and 40s are the time to get on top of it.

Is this just about people on TRT?

Nope — and that’s a really important distinction. Even if you’re not on testosterone therapy, long-term monitoring still matters. Why? Because your levels may decline naturally over time. Or because your one remaining testicle may not hold up the way you hope. Or because other aspects of treatment (like chemo or radiation) can have delayed effects that show up years down the line.

Bottom line: If you’ve had testicular cancer, you’re playing a different biological game now. You don’t need to panic. You just need to check in with your body — and your bloodwork — regularly.

And if you’re on TRT? That’s not a “fix it and forget it” scenario either. It’s a dynamic relationship — between your body, your medication, your lifestyle, and your goals.

So where does this leave us? It leaves us with a long-term health plan, not a short-term patch. One rooted in observation, intention, and ongoing dialogue with your care team.

In the next section, we’ll get into the less conventional stuff — some emerging research, a few surprising angles, and what most of the standard articles tend to leave out. Because this topic has more depth than even most experts give it credit for — and you deserve to know the whole picture.

Unique Insights and Lesser-Known Facts

Let’s be honest: after you’ve read enough articles or sat through enough medical appointments, a lot of the advice about testicular cancer and testosterone starts to sound the same. Maybe you’ve already heard the basics about diagnosis, symptoms, monitoring, and treatment options — and now you’re wondering, “Okay, but what’s really happening behind the scenes? What else don’t they usually tell you?”

Here’s where we dig into the outliers, the grey areas, and the little wrinkles that rarely make it into checklists.

Not all symptoms show up right away

A weird thing about testosterone deficiency after testicular cancer? Sometimes, the major symptoms show up months or even years after treatment. You can leave the hospital feeling pretty much yourself, then notice things start to shift quietly down the line — energy, motivation, sexual interest, even how you respond to stress or sleep.

Why does this happen? One possibility is that the remaining testicle (if you have one) tries to compensate, but over time the strain wears it down. Or your body adapts to lower levels for a while — until, suddenly, it doesn’t. The delayed hit is common, and it’s why some men don’t make the connection between their cancer history and later hormone problems.

Testosterone isn’t everything — but it affects everything

It’s easy to get tunnel vision about testosterone. Is it low? Is it high? What’s the “number?” But in reality, testosterone acts like a conductor in an orchestra — influencing a bunch of other hormones and systems, from cortisol to insulin to thyroid function. So sometimes, what feels like a testosterone problem is actually a tangled network of subtle hormonal shifts, all feeding off each other.

This is why a smart clinician will sometimes run a full hormone panel if you’re having persistent symptoms, not just a quick T check.

The survivor community is full of hacks and workarounds

Here’s something you don’t always hear in clinics: the lived experience of guys who’ve gone through this. You’ll find online forums and survivor networks where men share tips that rarely make it into medical guidelines, such as:

- Tricks for dealing with TRT side effects (for example, splitting your injection dose to smooth out hormonal peaks and valleys).

- Advice for handling awkward conversations — dating after cancer, talking about fertility, even explaining scars or prosthetic testicles.

- Emotional strategies that aren’t therapy, but still work — like “don’t minimize your experience,” or “find a buddy you can text when you’re feeling off.”

These peer-to-peer stories aren’t a substitute for medical advice, but they fill in the emotional gaps and offer solidarity. If you feel alone in this, chances are there’s someone else who’s walked the same weird path — and might have wisdom you won’t get in a doctor’s office.

Early detection still matters

This might seem basic, but the truth is a lot of testicular cancers are found by men themselves, not their doctors. That makes self-exam one of the most underrated tools around. It’s not about hypochondria — it’s about knowing what’s normal for your own body. A monthly self-check, ideally after a warm shower, is simple and fast. And it can literally save your life, or at the very least, lead to a less aggressive treatment plan with fewer long-term consequences.

Emerging research: it’s not all bad news

Here’s something encouraging: long-term outcomes for testicular cancer survivors, even those who end up on lifelong hormone replacement, are often quite good. Newer research is starting to clarify best practices for protecting fertility, minimizing treatment side effects, and improving quality of life — not just survival. There’s even promising data on the use of alternative therapies (like enclomiphene) and individualized hormone regimens that don’t just “replace T,” but aim for optimal functioning in the real world.

Clinical trials are ongoing for more targeted, less toxic chemotherapies, and for more subtle forms of hormonal support that may help survivors stay healthier, longer.

“Preventative” isn’t just a buzzword

There’s a growing recognition that cancer follow-up shouldn’t just be about recurrence. It’s also about prevention: preventing bone loss, cardiovascular decline, and mental health struggles that can creep in after the big battles seem won. Proactive care — meaning regular bloodwork, bone scans, counseling, and open conversations about sexual health — really does improve outcomes. It’s not about living in fear; it’s about building a life where you can actually look forward, not just look back.

So what’s the point of all these lesser-known facts? It’s this: the story of testicular cancer and low testosterone isn’t just about fighting disease or patching up what’s broken. It’s about understanding the full scope of what recovery can mean — physically, mentally, emotionally, and even socially. The “official” version isn’t wrong, but it’s rarely the whole story.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Will having one testicle after cancer mean I’ll have low testosterone?

Not necessarily. Many men with one healthy testicle maintain normal testosterone levels, though some experience symptoms of low T over time, especially after chemotherapy or with age. Regular check-ups are the best way to catch any changes early.

2. When and how should I check my testosterone after treatment?

It’s wise to check testosterone a few months after completing treatment, and then at least once a year—sooner if you’re feeling unusually tired, low in mood, or have other concerning symptoms. Testing in the morning gives the most accurate results.

3. Is testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) safe, and does it affect fertility?

TRT can be safe and life-changing for men who genuinely need it, provided it’s prescribed and monitored by a professional. However, TRT can reduce or eliminate fertility, so it’s important to discuss sperm banking and family planning before starting.

4. Can I still have children after testicular cancer treatment?

Many men can, but there is a real risk of infertility, especially if both testicles are affected or after chemotherapy. Sperm banking before treatment provides the most reassurance, but fertility sometimes returns over time. A semen analysis can clarify your current status.

5. What are the signs of low testosterone, and how does it affect mental health?

Symptoms include persistent fatigue, low sex drive, weaker muscles, mood swings, brain fog, and trouble sleeping. Low T can also impact mental health, contributing to depression, anxiety, and irritability — it’s a medical issue, not just an emotional one.

6. Are there natural ways to improve testosterone and what happens if low T is ignored?

Healthy lifestyle habits—like good sleep, regular exercise, stress management, and maintaining a healthy weight—support hormone health, but may not be enough if your body can’t produce enough testosterone after treatment. Left untreated, low T can increase long-term risks for bone loss, heart disease, and other serious health problems.

Closing Thoughts

If you’ve made it this far, you already know: the story of testicular cancer and low testosterone is bigger than any pamphlet or quick doctor’s visit. It’s not just about stats or symptoms — it’s about how you feel, how you function, and what you want out of your life after cancer.

This journey is layered. Sometimes it’s medical. Sometimes it’s emotional. Often, it’s a mix of both — with a side of uncertainty thrown in for good measure. And if you’re finding it confusing, or frustrating, or lonely, you’re not “doing it wrong.” That’s just what being human in this territory looks like.

So what should you do? Stay curious about your own health. Don’t settle for vague answers or dismissive advice. Ask the “dumb” questions (they’re never dumb). Keep your annual check-ups, trust your instincts, and find people you can actually talk to — whether that’s a doctor, a therapist, a friend, or someone who’s walked the same road.

And remember, “survivor” isn’t just a medical status — it’s a lived, ongoing process. You deserve not just to survive, but to actually thrive on the other side. So here’s to feeling better, staying engaged, and — as much as possible — shaping the rest of the story on your terms.