Can Endometriosis Turn Into Cancer?

Can Endometriosis Turn Into Cancer: The Full Guide

- Understanding Endometriosis and Its Cellular Behavior

- What Does Current Research Say About Cancer Risk?

- Cellular Changes That Suggest Malignant Potential

- Which Types of Cancers Are Most Commonly Associated?

- How Endometriosis-Associated Cancers Are Diagnosed

- Are Blood Tests Useful in Tracking Malignant Changes?

- Hormonal Influence and Its Role in Malignancy

- Genetic Mutations Shared by Endometriosis and Cancer

- How Often Does Malignant Transformation Happen?

- Risk Factors That May Contribute to Cancer Development

- What Makes Some Endometriosis More Dangerous Than Others

- Can Surgical Removal Prevent Cancer Later?

- Monitoring Endometriosis After Diagnosis

- Differences Between Endometriosis-Linked and Spontaneous Cancers

- Emotional Impact and Cancer Fear in Patients

- Current Research and Clinical Trials

- Fertility Considerations in High-Risk Patients

- Role of Hormonal Therapies in Long-Term Prevention

- How Family History Affects Endometriosis Prognosis

- Summary: What Every Patient Should Know

- FAQ – Can Endometriosis Turn Into Cancer?

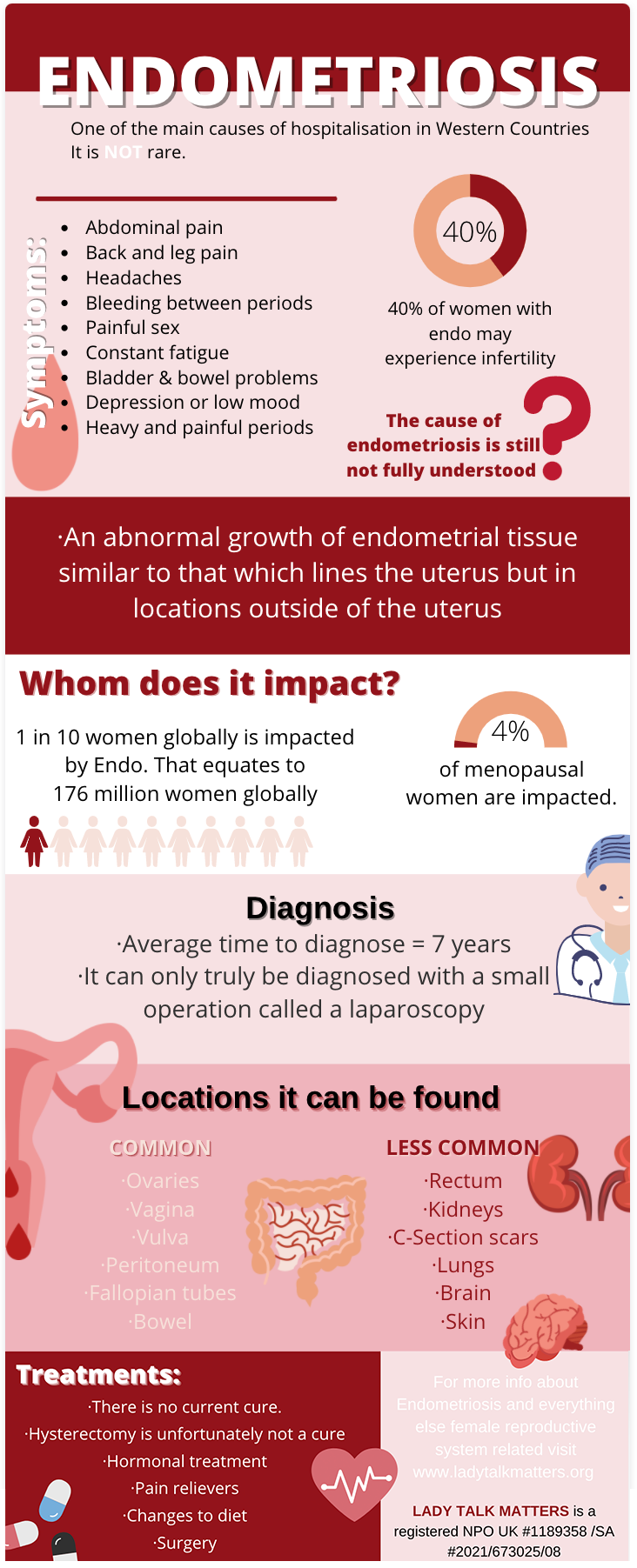

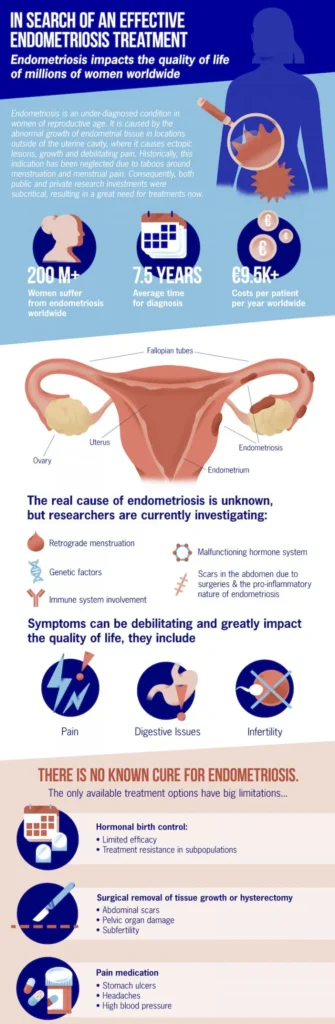

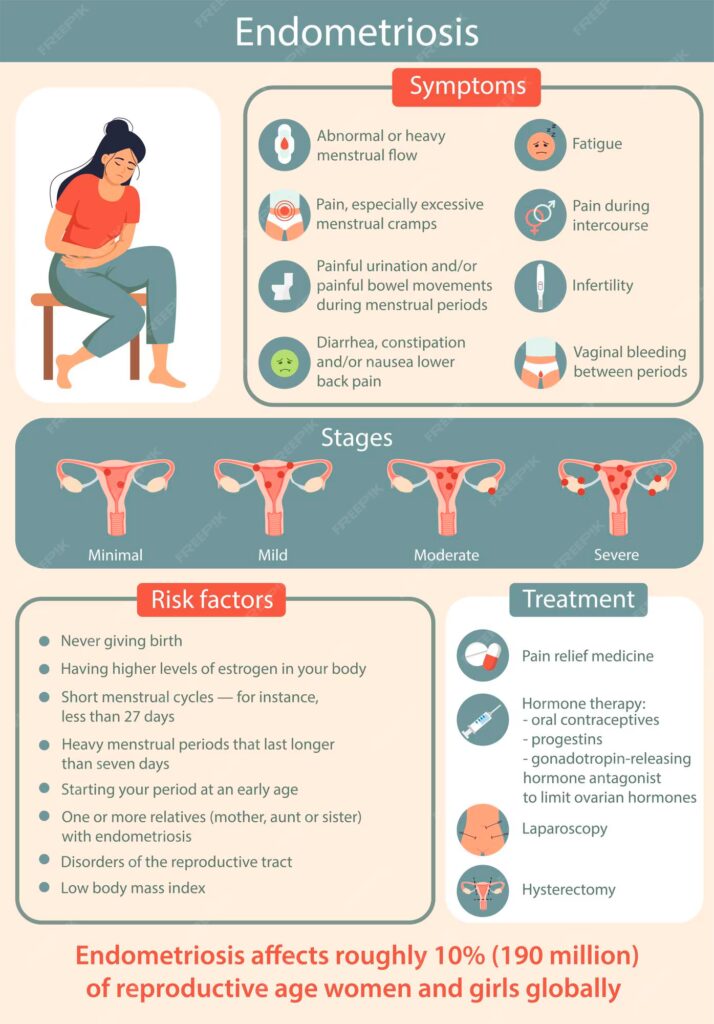

Understanding Endometriosis and Its Cellular Behavior

Endometriosis is a chronic condition in which tissue similar to the endometrial lining of the uterus grows outside the uterine cavity. These misplaced tissues respond to hormonal cycles, leading to inflammation, scarring, and pain. While endometriosis is generally benign, research has shown that it shares several biological traits with malignant tumors.

| Feature | Benign Endometriosis | Malignant Tumors |

| Hormone-responsive growth | Yes | Often |

| Invasion into surrounding tissues | Yes (locally) | Yes (locally and distantly) |

| Angiogenesis (new blood vessel growth) | Present | Highly active |

| Resistance to cell death | Moderate | High |

These overlapping features have prompted scientists to explore whether endometriosis can serve as a precursor to certain cancers, particularly ovarian cancer.

What Does Current Research Say About Cancer Risk?

Multiple studies have established a small but statistically significant increase in cancer risk among individuals with endometriosis. This risk primarily concerns ovarian cancer, although other gynecologic malignancies have been occasionally linked.

| Cancer Type Associated with Endometriosis | Relative Risk Increase | Typical Onset Age |

| Endometrioid ovarian carcinoma | 2–3 times higher | 45–55 years |

| Clear cell ovarian carcinoma | 3–4 times higher | 40–60 years |

| Low-grade serous carcinoma | Slight increase | Variable |

This connection is not a direct cause-and-effect relationship. Most individuals with endometriosis do not develop cancer, but the disease may act as a biologic foundation in rare transformations.

Cellular Changes That Suggest Malignant Potential

Endometriotic lesions may undergo atypical transformations over time, especially under long-term hormonal stimulation or in individuals with a family history of cancer. The transformation process is termed atypical endometriosis, considered a possible precancerous state.

Infographic: From Endometriosis to Malignancy

- Normal endometrial-like cells outside uterus

↓ - Chronic inflammation & estrogen exposure

↓ - Genetic mutations (e.g., ARID1A, PTEN)

↓ - Atypical hyperplasia (precancerous)

↓ - Endometrioid or clear cell carcinoma

Molecular studies have identified common mutations in both endometriotic lesions and associated cancers, suggesting that these genetic changes may precede malignancy.

Which Types of Cancers Are Most Commonly Associated?

While endometriosis has been tentatively linked to several malignancies, ovarian cancer remains the most strongly associated. Among subtypes, clear cell and endometrioid ovarian carcinomas stand out due to their shared molecular profiles with endometriotic lesions.

| Cancer Subtype | Key Features | Connection to Endometriosis |

| Endometrioid carcinoma | Gland-forming, estrogen-sensitive | Often arises from atypical endometriosis |

| Clear cell carcinoma | Aggressive, chemoresistant in some cases | Strongly linked to endometriotic cysts |

| Serous carcinoma | Most common ovarian cancer, high-grade | Rarely associated |

| Colorectal cancer | Very rare link | May co-exist with pelvic endometriosis |

In exceedingly rare cases, endometriosis has been reported to coexist or even transform into colorectal, uterine, or cervical cancers, though evidence remains limited.

How Endometriosis-Associated Cancers Are Diagnosed

The diagnostic process for cancers that may arise from endometriosis is often complex due to overlapping symptoms and the deep pelvic location of lesions. Diagnosis typically begins with clinical suspicion based on persistent or changing symptoms, followed by imaging and histological confirmation.

| Diagnostic Tool | Role in Evaluation |

| Transvaginal Ultrasound | Detects ovarian masses or endometriomas |

| MRI | Assesses deep infiltrating endometriosis and malignancy signs |

| CT Scan | Evaluates metastasis or advanced pelvic disease |

| CA-125 Blood Test | May be elevated in both endometriosis and cancer |

| Laparoscopy with Biopsy | Gold standard for diagnosis and histologic typing |

Histological analysis is crucial, as benign endometriosis and cancer can appear similar on imaging. Features like nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and glandular crowding suggest malignant transformation.

Are Blood Tests Useful in Tracking Malignant Changes?

While no blood test can definitively distinguish benign endometriosis from cancer, certain markers may help track disease progression or raise suspicion of malignancy. The most commonly used is CA-125, though it lacks specificity.

| Biomarker | Usefulness | Limitation |

| CA-125 | Elevated in both endometriosis and cancer | Poor specificity, affected by inflammation |

| HE4 | Higher specificity for ovarian cancer | Less affected by benign gynecologic disease |

| CEA | May be elevated in GI tract involvement | Nonspecific |

| LDH | Used in some ovarian tumors | Rarely specific to endometriosis |

In routine endometriosis care, blood tests are not typically used unless cancer is suspected. Monitoring is based more on imaging and symptom changes.

Hormonal Influence and Its Role in Malignancy

Estrogen plays a central role in the progression of endometriosis, promoting both proliferation and inflammation. Prolonged exposure to unopposed estrogen — whether endogenous or from hormone therapy — may increase the risk of malignant change.

| Hormonal Factor | Potential Effect |

| Endogenous estrogen | Stimulates growth of ectopic endometrial cells |

| Unopposed estrogen therapy | May accelerate atypical transformation |

| Progesterone resistance | Reduces natural checks on cell proliferation |

| Aromatase activity in lesions | Produces local estrogen, perpetuating disease |

Understanding hormonal pathways helps in both preventing progression and selecting appropriate therapies. Progesterone-based treatments and GnRH agonists are often used to suppress stimulation.

Genetic Mutations Shared by Endometriosis and Cancer

One of the most compelling connections between endometriosis and cancer comes from molecular studies. Several genetic mutations have been identified in both atypical endometriotic lesions and associated malignancies, suggesting a shared pathogenic pathway.

| Gene Affected | Role in Cell Regulation | Mutation Impact |

| ARID1A | Tumor suppression | Loss linked to clear cell and endometrioid carcinomas |

| PTEN | Regulates cell growth | Inactivation leads to uncontrolled proliferation |

| PIK3CA | Cell survival signaling | Mutations found in ovarian and endometrial cancers |

| KRAS | Cell division control | Associated with low-grade cancer transformation |

These mutations support the theory that some cases of endometriosis may follow a stepwise progression toward cancer — particularly in genetically predisposed individuals.

How Often Does Malignant Transformation Happen?

Although widely discussed, malignant transformation of endometriosis is considered rare. Most cases of endometriosis remain benign throughout a patient’s life. Studies estimate that less than 1% of endometriosis cases will progress to cancer.

| Statistic Type | Value or Range | Context |

| Lifetime cancer risk in women with endometriosis | 1.2–2.0% | Compared to ~1% in general population |

| Proportion of ovarian cancers linked to endometriosis | 10–15% | Mostly endometrioid and clear cell subtypes |

| Average time from diagnosis to transformation | 8–10 years | Usually after decades of disease persistence |

Thus, while endometriosis-related cancers are possible, they are exceptional rather than expected outcomes and typically follow long disease courses.

Risk Factors That May Contribute to Cancer Development

Not all individuals with endometriosis are equally at risk. Certain personal, clinical, and environmental factors appear to increase the likelihood of malignant transformation.

| Risk Factor | Explanation |

| Age over 45 | Malignant cases more common in perimenopausal women |

| Long-standing endometriosis | Especially when left untreated for years |

| Presence of endometriomas | Especially in ovaries, associated with transformation |

| Hormonal imbalance | Unopposed estrogen exposure |

| Family history of cancer | May reflect underlying genetic predispositions |

| Previous pelvic surgery | Scar tissue may complicate disease and surveillance |

Patients with one or more of these risk factors may benefit from closer surveillance and possibly prophylactic interventions.

What Makes Some Endometriosis More Dangerous Than Others

While the majority of endometriosis remains localized and stable, certain forms and features have been found to carry higher cancer risks. This often depends on the location, cellular makeup, and molecular behavior of the lesions.

| Type or Feature of Endometriosis | Associated Cancer Risk | Notes |

| Ovarian endometriomas | High | Especially if recurrent or persistent |

| Deep infiltrating endometriosis | Moderate | Lower than ovarian type but still under study |

| Superficial peritoneal endometriosis | Low | Rarely if ever transforms |

| Atypical histological features | High | Presence of dysplasia or cellular mutations |

This understanding guides treatment choices and long-term monitoring. In some cases, surgery may be preferred to mitigate future complications.

Can Surgical Removal Prevent Cancer Later?

Surgical removal of endometriotic lesions—especially ovarian endometriomas—may lower the risk of later transformation. However, surgery is not always a guarantee against recurrence or cancer development.

| Surgical Strategy | Purpose | Effect on Cancer Risk |

| Cystectomy (removal of endometrioma) | Removes abnormal tissue | May reduce risk if completely excised |

| Oophorectomy (removal of ovary) | For extensive or suspicious lesions | Significantly reduces ovarian cancer risk |

| Hysterectomy | For widespread disease | Only partially effective unless ovaries removed |

| Ablation | Destroys lesions but may miss deep tissue | Less effective at reducing long-term risk |

Surgical decisions must balance symptom relief, fertility preservation, and oncologic safety. In women no longer seeking fertility, more definitive surgery may be advised.

Monitoring Endometriosis After Diagnosis

For most patients, endometriosis is managed medically or surgically, but ongoing monitoring is essential, particularly in those at higher risk for transformation. The goal is to detect signs of progression or abnormal growth early.

| Monitoring Method | Purpose | Frequency (Typical) |

| Pelvic exam | Detect new or enlarging masses | Every 6–12 months |

| Ultrasound (TVUS) | Monitor ovarian cysts or endometriomas | Annually or as clinically indicated |

| MRI | Evaluate deep or complex lesions | Case-dependent |

| CA-125 or HE4 blood tests | Not routine; for high-risk cases only | Only with suspicious findings |

Importantly, the presence of a stable endometrioma without symptoms often doesn’t require intervention. However, growth, solid components, or pain changes should trigger further evaluation.

Differences Between Endometriosis-Linked and Spontaneous Cancers

Understanding how cancers arising from endometriosis differ from those that develop spontaneously helps refine both treatment and prognosis.

| Feature | Endometriosis-Linked Cancer | Spontaneous (Non-Endometriotic) Cancer |

| Common histology | Endometrioid, clear cell | Serous (most common) |

| Age at diagnosis | 40–60 years | Often later (postmenopausal) |

| Genetic mutations | ARID1A, PTEN, PIK3CA | TP53, BRCA1/2 |

| Growth pattern | May be indolent, localized | Often rapid and diffuse |

| Prognosis (if early stage) | Generally favorable | Depends on histology and stage |

These distinctions matter, as they influence chemotherapy response, recurrence risk, and survival outcomes. Early diagnosis of endometriosis-associated cancers typically offers a better outlook.

Emotional Impact and Cancer Fear in Patients

For many women, the chronic nature of endometriosis is compounded by fear of cancer, especially with increased media coverage or family history. While most cases remain benign, anxiety can influence treatment decisions and quality of life.

Infographic: Common Emotional Responses to Cancer Concerns in Endometriosis Patients

- Persistent anxiety over “what if”

- Misinterpretation of symptoms as malignancy

- Avoidance of gynecologic exams

- Stress-induced hormonal changes worsening endo symptoms

- Conflict between fertility goals and surgical options

Supportive counseling and accurate education are crucial in helping patients distinguish between perceived and actual risk, especially when decisions like oophorectomy or hysterectomy are on the table.

Current Research and Clinical Trials

In recent years, research has focused on the molecular mechanisms linking endometriosis to cancer, as well as interventions to mitigate risk.

| Study Type | Focus Area | Notable Developments |

| Genomic sequencing studies | ARID1A, PIK3CA, PTEN mutation mapping | Better understanding of mutation pathways |

| Biomarker trials | HE4, CA-125, microRNA panels | Potential early detection tools |

| Surgical outcome registries | Long-term effects of cyst removal or hysterectomy | Insight into recurrence and cancer rates |

| Immunotherapy trials | Use of checkpoint inhibitors in clear cell tumors | Emerging area under study |

Patients with complex cases may be eligible for clinical trials related to ovarian or gynecologic oncology. Discussion with a specialist is essential.

Fertility Considerations in High-Risk Patients

One of the most challenging aspects of managing endometriosis in patients at risk for cancer is balancing fertility preservation with medical safety. Ovarian surgery, especially oophorectomy, reduces future cancer risk but can also compromise reproductive capacity.

| Fertility Concern | Associated Cancer Risk Action | Fertility Impact |

| Recurrent ovarian endometrioma | Cystectomy may be recommended | Reduces ovarian reserve |

| Atypical endometriosis | Closer monitoring or excision | Varies by surgical extent |

| Clear cell transformation | Oophorectomy required | Ends natural fertility |

| Consideration for IVF | Post-surgical fertility option | May be limited by hormone therapy |

Fertility-sparing strategies may involve cryopreservation (egg or embryo freezing) or delayed surgery with strict surveillance. Each decision must be tailored to the individual based on cancer risk, age, and reproductive goals.

Role of Hormonal Therapies in Long-Term Prevention

Hormonal management remains a cornerstone of endometriosis treatment and may also help prevent malignant transformation by limiting estrogen-driven proliferation.

| Hormonal Treatment | Mechanism | Potential Role in Cancer Prevention |

| Progestins | Oppose estrogen, induce atrophy | May reduce atypical transformation |

| Combined oral contraceptives | Suppress ovulation, stabilize cycles | Long-term use linked to lower cancer risk |

| GnRH agonists | Induce pseudo-menopause | Effective for symptom suppression |

| Aromatase inhibitors | Reduce estrogen synthesis | Used in refractory or high-risk cases |

Long-term use of low-dose hormonal therapy has been associated with a decreased incidence of ovarian cancer, particularly in women with endometriomas or multiple surgeries.

How Family History Affects Endometriosis Prognosis

Family history of gynecologic or breast cancer may indicate a genetic predisposition that modifies endometriosis behavior. While endometriosis itself is not inherited in a Mendelian pattern, genetic studies suggest susceptibility loci that affect inflammation, estrogen signaling, and immune response.

| Family History Present? | Additional Considerations |

| Yes, ovarian or breast cancer | Consider genetic counseling and BRCA testing |

| Yes, endometriosis | Higher recurrence and severity risks |

| No | Standard surveillance may be appropriate |

When BRCA or Lynch syndrome is suspected, oncologic consultation and preventive options (e.g., risk-reducing surgery) may be considered, even in younger patients.

Summary: What Every Patient Should Know

Understanding the relationship between endometriosis and cancer involves recognizing both the rarity of transformation and the importance of risk management. The vast majority of individuals with endometriosis will never develop cancer, but a proactive, informed approach is crucial.

Infographic: Key Takeaways for Patients

- Endometriosis can rarely turn into ovarian cancer, mostly endometrioid or clear cell types.

- Risk increases with age, family history, and presence of ovarian endometriomas.

- Regular monitoring and early treatment of suspicious changes can reduce complications.

- Hormonal therapy and fertility preservation require individualized planning.

- Genetic counseling may be useful for those with family history of gynecologic cancers.

FAQ – Can Endometriosis Turn Into Cancer?

1. Is endometriosis itself considered a form of cancer?

No, endometriosis is classified as a benign gynecologic condition. Although it shares some cellular behaviors with cancer—like tissue invasion and estrogen responsiveness—it does not meet the criteria for malignancy in the vast majority of cases. Only in rare instances can certain forms of endometriosis develop into cancers, most notably ovarian.

2. Can endometriosis cause uterine cancer?

There is currently no direct evidence linking endometriosis to an increased risk of uterine (endometrial) cancer. However, both conditions are estrogen-sensitive and may coexist. Monitoring hormonal health and any changes in bleeding patterns is recommended in patients with both diagnoses.

3. How is atypical endometriosis different from regular endometriosis?

Atypical endometriosis is a histological subtype where cells show abnormal features under the microscope, such as nuclear enlargement and architectural crowding. These changes suggest a possible precancerous process and warrant more aggressive treatment or monitoring than typical endometriosis.

4. Does menopause reduce the risk of endometriosis turning into cancer?

Yes, menopause naturally reduces estrogen levels, leading to regression of most endometriotic lesions. However, cancer risk does not vanish completely, especially in patients with long-standing ovarian endometriosis. Postmenopausal bleeding or new pelvic masses should always be evaluated.

5. Can hormone replacement therapy (HRT) increase the risk of transformation?

Unopposed estrogen therapy, particularly in women with residual endometriosis post-hysterectomy, may stimulate remaining endometriotic tissue and potentially raise cancer risk. Combined estrogen-progestin therapy is considered safer, but all HRT decisions should be personalized.

6. Is cancer risk higher in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis?

Deep infiltrating endometriosis does not appear to carry the same transformation risk as ovarian endometriomas. However, it can cause chronic inflammation and complex pelvic disease, which may complicate detection of malignancy. Regular imaging may still be warranted.

7. Should endometriosis be removed as a preventive measure against cancer?

Not routinely. Preventive surgery may be considered in high-risk individuals—such as those with BRCA mutations or complex ovarian cysts—but in most cases, treatment focuses on symptoms, fertility goals, and individual risk profiles rather than cancer prevention alone.

8. How do doctors differentiate between a benign endometrioma and a malignant one?

Differentiation is based on a combination of imaging features (e.g., solid components, septations), tumor markers (e.g., CA-125, HE4), and histology. MRI is especially useful in identifying suspicious features, but definitive diagnosis requires surgical removal and biopsy.

9. Can men get endometriosis or related cancers?

Endometriosis is extremely rare in men but has been reported in isolated cases, often associated with prolonged estrogen therapy or hormonal disorders. These cases are exceptional, and the relationship to cancer risk in males remains anecdotal and unclear.

10. Are there vaccines that can prevent endometriosis-related cancers?

Currently, there are no vaccines specifically designed to prevent cancers linked to endometriosis. However, general HPV vaccination reduces the risk of cervical and some gynecologic cancers. Research into immunoprevention for ovarian cancer is ongoing.

11. Can endometriosis be mistaken for ovarian cancer on imaging?

Yes, endometriosis—especially ovarian endometriomas—can mimic cancer radiologically. Features such as thickened walls, mural nodules, or elevated CA-125 can overlap with malignancy, making surgical confirmation necessary in some cases.

12. Is it safe to become pregnant if you have high-risk endometriosis?

In most cases, yes. Pregnancy may even have a temporary suppressive effect on endometriosis due to hormonal shifts. However, patients with complex cysts or prior cancer history should undergo individualized evaluation before trying to conceive.

13. Can lifestyle changes help reduce cancer risk in endometriosis patients?

There is limited but growing evidence that maintaining a healthy weight, exercising regularly, and reducing chronic inflammation through diet may contribute to better hormonal balance and immune function, potentially lowering cancer risk.

14. Are there any early warning signs specific to endometriosis turning into cancer?

Signs such as rapid cyst growth, new pelvic pain in menopause, postmenopausal bleeding, or solid nodules seen on ultrasound may suggest transformation. However, these signs are nonspecific and need further diagnostic workup.

15. Should patients with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer be tested if they have endometriosis?

Yes, especially if there’s a personal or family history of BRCA-related cancers. Genetic counseling and testing can guide risk-reducing strategies and help patients make informed decisions about monitoring and treatment.