Can Dental Implants Cause Cancer?

- 1. Introduction to Dental Implants

- 2. Understanding Cancer Risks in Dentistry

- 3. Scientific Evidence: Do Dental Implants Cause Cancer?

- 4. Potential Factors Contributing to Cancer Near Implants

- 5. Expert Opinions and Consensus

- 6. Preventive Measures and Best Practices

- 7. Patient Testimonials and Case Studies

- 8. Addressing Common Myths

- 9. Innovations in Implant Technology

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

There’s a particular kind of fear that settles in when something foreign is introduced into the body. A pacemaker, a hip joint, a breast implant — or, more mundanely, a dental implant. It’s the kind of fear that asks, quietly but insistently: Is this safe? Could this cause something worse?

For dental implants, that question has taken on a particularly loaded form: Can they cause cancer?

It’s not just idle curiosity. It’s a question shaped by snippets of internet speculation, rare clinical anecdotes, and a general wariness of anything labeled “implant.” And because the mouth feels like such personal, vulnerable territory, the stakes feel higher. If you’re considering a dental implant — or already have one — and find yourself wondering whether this small metal fixture could somehow set off a chain reaction toward something as serious as cancer, you’re not alone.

This article was written for you.

Not to reassure you blindly. Not to dismiss your concern. But to walk you through the full story — the real story — with clarity, precision, and yes, healthy skepticism. We’ll dive into what science actually says, where the worries come from, and what you can do to keep your oral and systemic health thriving.

You won’t get oversimplifications here. You will get nuance. You’ll get facts, clinical insights, and perspectives from both sides of the treatment chair — all stitched together into something honest and comprehensive. This is the article that takes the fear out of the shadows and holds it up to the light.

Because when it comes to your health, the final answer shouldn’t come from a half-read forum post or an offhand comment. It should come from real data, real experience, and real medicine — all interpreted with respect for your intelligence and agency.

Introduction to Dental Implants

Let’s start at the root — or in this case, the artificial root.

If you’re here, you’ve probably heard conflicting things about dental implants. Maybe someone mentioned they’re a “permanent fix” for missing teeth, while someone else warned they “might cause cancer.” That’s a pretty wide spectrum — and understandably unsettling.

So let’s cut through the chatter.

What exactly are dental implants?

Think of a dental implant as a substitute tooth root. It’s usually made from titanium — yes, the same metal used in medical-grade joint replacements and even aerospace engineering. Why titanium? Because your body typically doesn’t fight it off. Instead, over a few months, your jawbone actually fuses with it in a process called osseointegration. That fusion is what makes implants so durable and stable.

After the implant is embedded in the jaw, a connector (called an abutment) is added, followed by a custom crown that mimics your natural tooth. The result? A restoration that looks, feels, and functions like the real thing — and in many ways, even better.

But here’s the kicker: it’s not just a cosmetic fix. Tooth loss doesn’t only affect how you chew or smile. When you lose a tooth, your jawbone begins to shrink in that area due to lack of stimulation — a process called bone resorption. Implants help prevent this, maintaining both function and facial structure.

Just how common are implants?

Very. Dental implants are no longer niche — they’re mainstream. Over 5 million implants are placed every year in the United States alone. That number grows annually, driven by aging populations, better materials, and increasing public awareness.

This leads to a natural question:

If implants are so common, shouldn’t we already know everything about their long-term safety?

Great question. And yes — to a large extent, we do. But as with any medical technology, continued vigilance is essential. Which is why we’re asking another important question here: can dental implants cause cancer?

Before we go there, let’s zoom out briefly and explore why this question even comes up in the first place.

Why would anyone suspect a cancer link in the first place?

It might seem like a leap — but it’s not as far-fetched as it sounds. When you insert a foreign material into the human body, whether it’s a breast implant, a hip joint, or a dental implant, it’s fair to ask what that long-term exposure might do. Could it cause chronic inflammation? Could that inflammation lead to tissue changes? And could that lead to something more sinister?

We also live in a time when public awareness of medical risks — real and speculative — is at an all-time high. Social media and anecdotal accounts can magnify even the rarest complications. And occasionally, isolated cases make it into the scientific literature, often without context. That’s not necessarily a bad thing — but it does make it harder to separate signal from noise.

So here’s what we’ll do next: we’ll break down the actual science. The studies. The case reports. The biological plausibility (or lack thereof). And most importantly, we’ll give you a grounded view of what’s actually known — versus what’s only suspected or speculated.

Because if you’re going to have a titanium post fused into your jaw, you deserve more than just marketing language or vague reassurances. You deserve real answers.

Let’s dig in.

Understanding Cancer Risks in Dentistry

Any medical or dental procedure, no matter how routine, carries some level of risk. That’s not alarmist; it’s just the nature of working with biology. But when the word “cancer” enters the picture, everything sharpens. Understandably so. Cancer isn’t just a complication — it’s a life-altering diagnosis. So when someone hears that a dental implant, of all things, might somehow raise that risk, the response is visceral: Wait — what?!

Where does this concern even originate?

Much of it has to do with the growing awareness around how chronic inflammation can influence cancer risk. Decades ago, we treated inflammation as more of a nuisance — swelling, soreness, heat, maybe a bit of redness. Now we understand it’s far more serious. Chronic inflammation has been linked to several forms of cancer, from colorectal to liver to gastric. So it’s not illogical to wonder: if an implant were to cause long-term irritation in the mouth — especially near mucosal tissues — could that set the stage for something more dangerous?

There’s also the historical baggage of other medical implants. You’ve likely heard of concerns surrounding breast implants and lymphoma, or hip replacements leaching metal ions. It’s not apples to apples — but the public mind tends to group these risks together under one uneasy umbrella: implants + long-term exposure = unknown cancer risk.

Fair. But let’s anchor this specifically in dentistry.

Does dentistry have a known relationship with cancer risk?

Here’s what the science tells us: generally speaking, routine dental procedures do not cause cancer. If anything, proper dental care reduces your cancer risk by supporting systemic health. Untreated periodontal disease, for example, is a known inflammatory condition — and inflammation, again, is a key piece of the cancer puzzle.

But it’s also true that certain conditions in the mouth can be precancerous. Leukoplakia, erythroplakia, and lichen planus are examples of lesions that, if left unchecked, can sometimes evolve into oral cancers. These aren’t caused by dental treatment, but their presence means that oral health is intimately connected with early cancer detection — and by extension, with the broader conversation about implants.

Concerns about oral health and cancer risk aren’t new. A related question that often comes up is whether titanium implants carry any risk, and the evidence there is worth a look.

So are dental implants different? Do they uniquely pose a risk?

This is where nuance matters.

Implants are unique in that they remain in your body — indefinitely. They integrate into bone. They sit below the gumline. They must coexist with living tissue 24/7. That long-term interaction opens the door, at least theoretically, to complications: infection, rejection, inflammation, and, in extremely rare cases, neoplastic changes (i.e., cancerous transformations).

Some worry that the metal itself might be a factor — especially since titanium, while biocompatible, can corrode slightly over time in the wet, enzymatic environment of the mouth. Trace particles can enter surrounding tissues. But here’s the key: no high-quality studies have established a causal link between these particles and any form of cancer. In fact, most of what we know about titanium suggests it’s one of the most inert and safest materials available for long-term human use.

Still, context matters. The oral cavity is a dynamic, bacteria-rich environment. Implants can fail. They can develop peri-implantitis — a gum infection not unlike periodontitis — and that inflammation, if allowed to smolder, can contribute to a local breakdown of tissue. Could that ongoing inflammation, in theory, play a role in cell mutation over time? Theoretically, yes. But science hasn’t shown that it does.

And that’s the difference between biological plausibility and proven causation. A possibility isn’t a conclusion.

This is the territory where concern often outpaces evidence — a gray area of “we don’t have proof it causes cancer, but we also haven’t ruled out every possible long-term scenario.” That’s not an indictment of implants. That’s how responsible science works: cautiously, rigorously, incrementally. And most importantly, it stays anchored in data — not anxiety.

Scientific Evidence: Do Dental Implants Cause Cancer?

Let’s tackle this head-on: is there any credible scientific evidence that dental implants cause cancer?

Short answer: no — at least, not in the way the word cause is typically understood in medicine or epidemiology.

But that doesn’t mean the conversation ends there. Because when someone asks, “Can dental implants cause cancer?” they’re not always asking for a binary yes-or-no. They’re asking: Has this been studied? Are there case reports? Is there any reason to worry? These are entirely fair questions — and the answers, as always, live in the details.

First, what does the literature actually say?

When we look at large-scale studies — the kind that track thousands of patients over years — there is no statistically significant increase in cancer incidence among people with dental implants. This includes cancers of the oral cavity, surrounding soft tissues, and even systemic cancers.

A 2016 population-based cohort study published in Clinical Oral Implants Research followed over 4,000 implant patients and compared them to a matched control group. Their findings? Implant patients did not experience higher rates of oral cancer than the general population. In fact, in some cases, implant recipients actually had lower rates — likely because people who invest in implants tend to be more proactive about oral health and hygiene.

Another study from the Journal of Dental Research reviewed cancer cases appearing at or near dental implants and concluded that these were extremely rare events — and even then, more likely related to pre-existing pathology than to the implant itself.

But what about the case reports?

This is where things can get muddy. A handful of isolated reports have documented cancers — mostly squamous cell carcinoma — developing adjacent to dental implants. These are the stories that ripple out through forums, podcasts, and even a few alarming blog posts. They’re real. They’re published. And yes, they deserve to be read closely.

But here’s the thing: case reports don’t prove causation. They describe a coincidence in time and place, not a definitive chain of cause and effect. Most of these cases occurred in patients who were already at higher risk for oral cancer — smokers, those with histories of leukoplakia, or individuals with long-term poor oral hygiene. In several instances, the cancerous lesion may have predated the implant but gone unnoticed during placement.

Another possibility: the chronic inflammation caused by peri-implantitis (the inflammatory disease affecting tissues around implants) may have provided a microenvironment conducive to carcinogenesis. Again — biologically plausible. But we’re talking about one case here, another there. That’s not a pattern. That’s not a signal. That’s anecdote.

And the scientific community treats anecdote as a beginning, not a conclusion.

So why does this still make people nervous?

Because “no evidence of harm” isn’t the same as “guaranteed safe forever.” It’s a subtle but important distinction. Every material in medicine — from pacemakers to breast implants to dental amalgam — exists in a state of ongoing scrutiny. And rightfully so. That’s how progress works.

But the fear surrounding dental implants and cancer often stems not from the data itself, but from how little laypeople feel they can trust the data. Especially in an age of growing skepticism toward medical authorities, many patients feel more comfortable relying on anecdotal stories or personal research.

Let’s not dismiss that. But let’s also look at the balance of probability. If there were a measurable, replicable, and statistically significant increase in cancer risk among dental implant users, we’d be seeing an uptick in oral cancer that would be hard to miss — especially given how many implants are placed each year globally (north of 10 million and rising). That uptick doesn’t exist. In fact, oral cancer rates are relatively stable, with known links to tobacco, alcohol, HPV, and poor oral hygiene — not implants.

And titanium? Still the gold standard.

Some critics have pointed to concerns over titanium wear particles, arguing that microscopic debris may leach into surrounding tissues and potentially cause DNA damage. But again, this rests more in theory than in demonstration. Titanium has been studied extensively for its biocompatibility, and while minor corrosion in the oral environment is acknowledged, the amounts are vanishingly small and not shown to be carcinogenic.

If anything, the introduction of newer implant materials like zirconia (a ceramic alternative) is driven more by aesthetics and allergy concerns than any compelling evidence of cancer risk.

Bottom line: if implants were triggering cancer on any meaningful scale, we would know by now. What we have instead is a small constellation of rare, isolated events — each one worthy of examination, but none forming a pattern that points to causation.

Next, we’ll look at those contributing factors that might amplify risk in unique scenarios. Because while implants themselves don’t appear to be carcinogenic, the environment around them — your habits, your hygiene, your immune responses — that’s where the nuance begins.

Potential Factors Contributing to Cancer Near Implants

Let’s suppose, for a moment, that someone does develop a malignancy in the area around a dental implant. Does that mean the implant caused it? Not necessarily. But it does beg a deeper question: What else might be at play in that microenvironment?

Because while the implant itself — particularly if it’s titanium — is not known to be carcinogenic, the biological contextinto which it’s placed matters. And it matters a lot.

Chronic inflammation: the slow-burning fuel

Here’s where we need to talk about one of cancer’s lesser-known co-conspirators: chronic inflammation. Unlike the acute swelling and redness you might experience from a stubbed toe or paper cut — which are actually signs your body is healing — chronic inflammation is sneakier. It smolders. It’s persistent. And when it goes unchecked, it can quietly alter your tissues at the cellular level.

This is not theoretical. Inflammatory diseases are directly linked to increased cancer risk across multiple organ systems: inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer, hepatitis and liver cancer, chronic gastritis and gastric cancer. The oral cavity is no exception.

In the context of dental implants, the condition to watch out for is peri-implantitis. It’s the implant version of gum disease — a slow, destructive process where the tissues around the implant become inflamed and begin to recede. Bone loss follows. If left untreated, the implant can fail.

But peri-implantitis does more than threaten the integrity of your new tooth. It creates a persistently inflamed environment. And chronic inflammation, again, is one of the well-established risk factors for cellular mutation and — potentially — neoplasia (abnormal tissue growth).

To be clear: there is no definitive evidence that peri-implantitis causes cancer. But if a malignancy appears in the vicinity of an implant, and that area has been inflamed for years, it’s reasonable to ask whether the inflammation played a role. Not as a direct cause, but as a catalyst. Like the difference between a match and dry wood.

The role of local trauma and persistent irritation

Another factor that occasionally crops up in case studies is repeated trauma to the soft tissues near an implant — usually from ill-fitting prosthetics or rough implant edges. When the mucosa is constantly irritated, especially if there’s a sharp edge rubbing the same spot day after day, the risk of local dysplasia (pre-cancerous tissue changes) may increase.

This isn’t limited to implants. Poorly fitting dentures have been implicated in similar processes. The mouth, after all, is lined with thin, rapidly renewing tissue — and that tissue doesn’t love being battered day in and day out.

Now, is this trauma enough on its own to cause cancer? Likely not. But when combined with other risk factors — smoking, poor hygiene, genetic susceptibility — it becomes part of a more complex puzzle.

Let’s talk materials — again, but deeper this time

We’ve already established that titanium is the default material for dental implants. It’s used because the body typically treats it like an old friend: non-reactive, stable, and incredibly strong. But no material is perfect.

In a small subset of individuals — we’re talking a fraction of a percent — titanium can provoke hypersensitivity reactions. These are not cancer, to be clear. But they can trigger chronic low-grade inflammation, itching, or mucosal irritation. And once again, inflammation is the common denominator.

There’s also the growing conversation around nano-debris: microscopic particles that may be released from the implant’s surface through wear, corrosion, or mechanical stress. Do these particles accumulate in surrounding tissues? Sometimes, yes. Do they cause mutations? As of now, no reliable human evidence supports that conclusion. In animal studies, extremely high concentrations have shown some concerning effects — but these are not conditions that mimic real-world use.

It’s worth noting that alternative materials like zirconia are increasingly being used, not because titanium is unsafe, but because zirconia is more aesthetic (it’s white, not silver-gray) and doesn’t conduct electricity — a theoretical concern in electrically sensitive patients. But from a cancer risk standpoint, there’s no compelling evidence suggesting zirconia is safer or more dangerous. It’s just different.

Lifestyle: the ever-present variable

One of the most consistent threads in every case involving cancer near an implant is this: the person often had other, much more potent risk factors. Smoking is the big one. Tobacco use is hands-down the most significant modifiable risk factor for oral cancer. Add alcohol into the mix — particularly heavy use — and you’ve created a synergistic effect. The two don’t just double your risk; they multiply it.

Poor oral hygiene also plays a significant role. If bacteria are allowed to flourish around an implant, they drive inflammation. If that inflammation persists, they damage tissue. And damaged tissue is, again, more vulnerable to mutations.

All this reinforces one central point: the implant isn’t acting in isolation. It’s interacting with your biology, your habits, your hygiene — and your history.

So, could cancer occur near an implant? Yes, but rarely — and usually in the presence of other red flags. The implant itself is unlikely to be the villain. At worst, it may be the stage where a much more complicated drama is unfolding.

| Risk Factor | Evidence Strength | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco use | Very high | Leading modifiable risk factor for oral cancers. |

| Excessive alcohol consumption | High | Synergistic with tobacco, especially long-term. |

| HPV infection (especially HPV-16) | High | Strongly associated with oropharyngeal cancers. |

| Poor oral hygiene | Moderate | Increases chronic inflammation and infection. |

| Chronic irritation (dentures, rough restorations) | Low | Can contribute locally over long periods. |

| Dental implants | Very low to negligible | No proven causal link; risk tied to maintenance. |

In the next section, we’ll pull back to the broader expert consensus. What do implantologists, oral surgeons, and oncologists actually think about this issue? What are the professional societies saying? Because when we zoom out from the rare case reports and theoretical concerns, we find a reassuringly consistent picture — and it’s worth hearing.

If you’re focusing more on routine dental procedures, here’s what science says about dental X-rays and their ability to detect or miss cancer.

Expert Opinions and Consensus

At this point, you’ve heard a lot of plausible mechanisms, rare edge cases, and scientific context — but what do the professionals who live and breathe this stuff actually think?

The short version? They’re not worried. At least not in the way that sensational headlines or anecdotal social media posts might suggest.

Let’s zoom out and look at what the real consensus says.

The professional stance: implants are safe

Across every major dental and medical body — from the American Dental Association (ADA) to the International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) and the European Association for Osseointegration (EAO) — the message is consistent: dental implants are considered a safe, effective, and evidence-backed treatment for tooth loss, with no established link to cancer.

That’s not a vague endorsement. These organizations regularly review the literature, update guidelines, and convene expert panels to reassess the data. If there were a credible risk signal — even a small one — you can bet they would address it.

And that’s not to say these groups are complacent. Dentistry is a dynamic field. Materials, methods, and long-term outcomes are constantly being scrutinized. But scrutiny doesn’t mean suspicion. It means vigilance. And when decades of cumulative patient data show no pattern of cancer development associated with implants, that says something.

The clinicians’ perspective

Talk to oral surgeons and periodontists — the people who place and monitor implants day in and day out — and the story becomes even more grounded.

These are specialists who’ve worked with hundreds, sometimes thousands, of implant cases over their careers. They’ve seen successful osseointegration. They’ve seen occasional failures (usually mechanical or infection-related). But ask how often they’ve seen a malignancy develop at or near an implant site? You’ll get the same answer, over and over: almost never.

Not because they’re ignoring it, but because it simply doesn’t happen with any frequency that would raise alarms.

In fact, many of these professionals go further: they argue that dental implants often improve overall oral health, not compromise it. By stabilizing the bite, preventing bone loss, and encouraging regular dental follow-up, implants contribute to long-term health in a way dentures or bridges may not. You’re less likely to ignore your dental care when you’ve invested in something permanent.

It’s also worth noting that implants are often placed after a thorough assessment — including medical history, oral cancer screening, radiographs, and sometimes even biopsy of suspicious tissue. If something worrisome is brewing, it usually gets caught early, before the implant ever goes in. In other words, the process of getting an implant can actually become a checkpoint for broader health monitoring.

The reality of professional liability

Here’s another layer that people sometimes overlook: risk management. In the medico-legal world, dentists and surgeons are not rewarded for downplaying risk. Quite the opposite. If there were even a whiff of credible concern about implants and cancer, you can bet the consent forms would be updated, the insurance policies rewritten, and the lawsuits flying.

But that hasn’t happened.

Why? Because there’s no surge in cancer-related implant claims. No flood of litigation. No undercurrent of suppressed data. Not even among populations most likely to challenge the medical system when something goes wrong.

When you step back and view the field through this lens — clinical practice, scientific consensus, and legal oversight — it becomes clear that the prevailing opinion is rooted not in wishful thinking, but in accumulated, reproducible experience.

Skepticism is healthy — but so is perspective

Now, does that mean we stop asking questions? No. It means we ask better ones.

There’s nothing wrong with being cautious, especially when something is going into your body for the long haul. And if you’re the kind of person who reads medical research, checks source citations, and wants to know what’s not being said — good. That kind of thinking has driven some of the most important medical advances of our time.

But it’s also worth knowing when a question has been asked — and answered — over and over, in multiple countries, in different populations, and through different investigative lenses.

And the answer here, so far, is reassuring: no causal link between dental implants and cancer has ever been established. Not by science, not by consensus, and not by clinical experience.

Preventive Measures and Best Practices

By now, it should be clear that the question “Can dental implants cause cancer?” isn’t just about the implant itself — it’s about everything that surrounds it. The tissues, the maintenance, the habits. So if the implant isn’t the threat, but the environment around it could be, then it naturally follows: what can you do to make that environment as healthy and low-risk as possible?

This is where things get empowering. Because while we can’t always control our genetic predispositions or the rare edge cases of medical uncertainty, we have a tremendous amount of influence over our daily biological landscape — especially in the mouth.

First, let’s talk oral hygiene — and not in the generic, brush-and-floss way

The oral cavity is one of the most biodiverse environments in your body. More bacteria live here than in your gut, your skin, or anywhere else — and many of them are beneficial. But when balance tips into dysbiosis, that’s when inflammation begins. And once that becomes chronic, it sets the stage for all kinds of problems: peri-implantitis, tissue breakdown, bone loss, and — yes — possibly even malignancy, if other risk factors are present.

So oral hygiene isn’t about chasing some arbitrary dental ideal. It’s about controlling inflammation. That’s the goal. And controlling inflammation starts with consistency.

Daily brushing and interdental cleaning (yes, that includes floss or a water flosser) reduce the bacterial load that triggers your body’s immune response. Less immune response means less tissue damage. Less damage means fewer opportunities for aberrant cells to proliferate. It’s not just cosmetic. It’s cellular.

For implant patients in particular, hygiene protocols need to be precise. Soft-bristle brushes. Low-abrasive toothpaste. Antimicrobial rinses as needed — but not obsessively, since overuse can disrupt healthy flora. And if you think a power toothbrush is just a luxury, think again. Clinical studies consistently show they reduce plaque more effectively than manual brushing, especially around complex structures like implants and abutments.

Regular dental checkups: the underappreciated cancer screening

Let’s call this what it really is — early detection. Every dental visit is a chance to catch something before it becomes something else. Dentists are trained not only to assess your restorations, but to examine soft tissues, feel for abnormal nodes, and spot changes in color, contour, or consistency that might indicate precancerous changes.

These aren’t scare tactics. They’re just smart medicine.

Implants don’t need heroic maintenance, but they do need watchful maintenance. Radiographs to assess bone stability. Probing depths around the implant. Monitoring for signs of soft tissue irritation. These visits may seem routine, but they’re doing heavy diagnostic lifting — often without you even noticing.

And yes, let’s be honest: the moment something feels off — an ulcer that won’t heal, a bump that wasn’t there last month, a persistent bad taste — that’s your cue. Don’t rationalize it. Don’t self-diagnose. See your dentist or periodontist. The earlier a problem is identified, the more options you have.

Lifestyle: where the real risk lives

If there’s one part of this whole discussion that doesn’t get nearly enough oxygen, it’s lifestyle. Tobacco, alcohol, nutrition — these are the three-legged stool upon which much of oral cancer risk rests. And they’re often far more impactful than whether or not you’ve got a piece of titanium in your jaw.

Let’s start with the obvious: tobacco is a carcinogen. Smoking increases your risk for oral cancer sixfold. Chewing tobacco? Even worse. Not only does it expose your mucosa to direct chemical carcinogens, it also increases mechanical irritation — a double hit.

Alcohol isn’t benign either. In small amounts, the risk may be minimal, but chronic use — especially when paired with tobacco — significantly magnifies cancer risk. The combination isn’t just additive. It’s multiplicative.

And then there’s nutrition. Diets low in fresh fruits and vegetables and high in processed foods and sugars contribute to systemic inflammation and oxidative stress — two known accelerators of cellular damage. The Mediterranean diet, rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, is associated with reduced cancer incidence across the board. The mouth benefits, too.

So no, implants don’t operate in a vacuum. They live in a system. And the choices you make about that system — what you eat, how you clean, what you avoid — shape your outcomes far more than the implant material ever could.

Prevention isn’t flashy. It’s not the kind of thing that makes headlines. But it is quietly, unfailingly powerful. Because in the end, the safest implant is the one placed into a body that’s cared for. Not perfectly. Not obsessively. But consistently.

Patient Testimonials and Case Studies

Statistics are powerful — they give us the big picture, the wide-angle view. But when it comes to health decisions, especially something as intimate as what goes into your mouth, numbers only go so far. What people often want to know is: What happened to someone like me? Did it work? Did anything go wrong? If so, how was it handled?

This is where stories come in. Real-life experiences take the abstract and make it tangible. They don’t replace data — but they enrich it.

A successful, unremarkable story — which is exactly the point

Take James, a 58-year-old architect from Portland. He lost a molar after a botched root canal and spent two years putting off the implant. Why? Because, in his words, “I spiraled down a Reddit rabbit hole about cancer risks, metal toxicity, and all kinds of stuff I couldn’t verify.”

Eventually, he talked it through with his dentist — not just in a five-minute chairside chat, but during a full consult where they went through the literature together. James ended up getting the implant. That was eight years ago. It’s stable, clean, and pain-free. He flosses with religious dedication now, not because of the implant, but because he understands the systemic stakes of oral health.

The most remarkable thing about James’s story is how unremarkable it is. And that’s what makes it powerful. Millions of people have stories like his — not dramatic, not flashy, but quietly successful. And in a media environment that often amplifies the worst-case scenario, that ordinariness is a kind of quiet reassurance.

When things go sideways — and still resolve

Then there’s Petra, 67, a retired teacher from Birmingham, who did experience a complication. About six months after her implant placement, she noticed persistent gum tenderness. Her hygienist flagged early signs of peri-implant mucositis — a mild inflammation that hadn’t yet progressed to peri-implantitis, but could if ignored.

The intervention? Local debridement, antimicrobial irrigation, and a reassessment of her home care routine. Petra admitted she’d been using a whitening toothpaste with a high abrasive index — not ideal for implants. She switched to a gentler paste, upgraded to a sonic brush, and incorporated an oral probiotic.

The tenderness resolved. Her next three follow-ups showed stable tissue and no bone loss.

It’s a small story, but it illustrates something important: even when problems emerge, they don’t need to spiral into catastrophe. The body wants to heal. The system works — if you work with it.

One of the rarest cases — and the need for nuance

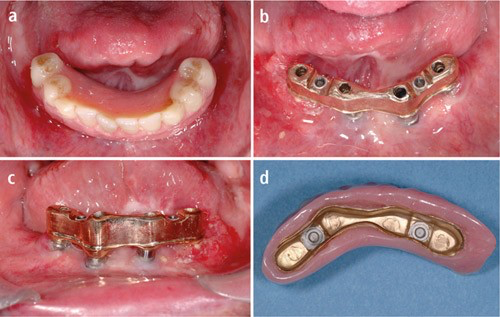

Now let’s acknowledge the outliers. There are case reports of cancer arising near implants. One involved a 72-year-old male with a history of smoking and untreated leukoplakia. He presented with a lesion at the site of an implant that had been placed four years prior. Biopsy revealed squamous cell carcinoma.

The implant was removed during surgical excision, not because it caused the cancer, but because the tissue surrounding it had become part of the malignant field. In follow-up discussions, the surgical team made a point to note that the cancer’s origin likely predated the implant, and that the implant site had simply masked a slowly evolving lesion.

This kind of case isn’t meant to scare — it’s meant to underline the importance of comprehensive screening beforeimplant placement and close monitoring afterward. It’s a textbook example of correlation, not causation. But it also shows that vigilance isn’t paranoia. It’s just good medicine.

What these stories tell us

If you’re looking for a smoking gun — a single story where a healthy patient received a dental implant and later developed cancer that was conclusively linked to the device — it doesn’t exist. Not in the literature, not in clinical databases, not in malpractice claims.

What you’ll find instead are stories like James’s: uneventful, lasting, and quietly successful. Or Petra’s: minor complication, managed well, with full recovery. And occasionally, yes, you’ll find patients with complex histories who develop serious pathology. But in nearly every case, the implant is incidental — a bystander to a larger health picture already in motion.

And that’s the takeaway: implants are not passive or inert in the sense that they disappear from your consciousness — they do require care. But they are stable. Predictable. And in most patients, deeply reliable.

And in terms of signs to watch out for, How Fast Oral Cancer Spreads offers a good breakdown of symptoms and timing.

Addressing Common Myths

By now, if you’ve read this far, you already know more about dental implants and cancer risk than most people do. You’ve seen the data, considered the clinical insights, and weighed the rare outliers against the massive tide of uneventful outcomes. But outside this evidence-based bubble, there’s another current running — and it’s powered not by facts, but by myths.

These myths don’t emerge from nowhere. They often start with a kernel of truth or a misunderstood study, get amplified by online echo chambers, and then spread as cautionary tales, half-truths, or full-on pseudoscience. And unfortunately, once they take hold, they’re sticky — even in the face of well-reasoned counterpoints.

Let’s be honest: people don’t spread these myths out of malice. They do it because they’re scared, confused, or trying to protect someone they care about. But when fear substitutes for science, it doesn’t just obscure the truth — it can actively harm decision-making.

Myth: “Titanium in your body leaches toxic metals that cause cancer.”

This one crops up all the time in holistic dentistry circles, often accompanied by alarming phrases like “metal poisoning” or “bioaccumulation.” It sounds terrifying. Who wants to imagine their jawbone slowly releasing carcinogenic particles into their bloodstream?

But here’s the reality: titanium is one of the most biocompatible materials ever studied. It’s used not only in dental implants, but in orthopedic hip and knee replacements, spinal fusions, and even cardiac devices. If titanium were toxic at the levels used in implants, we would have a full-blown public health crisis on our hands — and we don’t.

Yes, minute amounts of titanium oxide particles can wear off from the implant surface over time. But studies show that these are well below levels known to cause harm in humans. They are inert, and the body typically encapsulates or clears them without issue. Moreover, no credible study has demonstrated a mutagenic or carcinogenic effect of titanium exposure in vivo at doses relevant to dental implantation.

Still, if you’re one of the few individuals with a suspected titanium sensitivity — and you’ve been tested, not just self-diagnosed — there are alternatives like zirconia. But opting for these materials based on internet alarmism rather than clinical necessity doesn’t make the process safer. It just makes it more complicated.

Myth: “Cancer formed near an implant, so the implant caused it.”

Here we run into the classic logical fallacy: post hoc ergo propter hoc — after this, therefore because of this.

If a patient develops cancer near an implant site, it’s completely reasonable to ask whether there’s a link. But asking is not the same as concluding. These are often older patients, sometimes smokers, occasionally with pre-cancerous lesions that went undetected. The implant didn’t create the cancer — it happened to occupy the same space. That’s not causality. That’s coincidence with a side of confirmation bias.

In fact, in many of these rare cases, a deeper look reveals that the cancerous transformation likely began before the implant was even placed. And the implant site — with its increased visibility and follow-up — actually facilitated earlier diagnosis, not delayed it.

Myth: “Foreign objects in the body always increase cancer risk.”

This one is rooted in a general suspicion of medical implants — and again, it’s not without precedent. There are medical devices that have been associated with increased cancer risk, such as textured breast implants and a rare lymphoma. But equating one device with another is like comparing apples to carburetors. The materials, anatomical placement, and mechanisms of interaction with tissue are completely different.

Dental implants are not passive sacks or synthetic chemicals. They are solid, inert structures that do not leach hormones, don’t degenerate in the same way, and do not stimulate the immune system in the same fashion. Lumping them into the same risk category because they’re also “foreign” is conceptually lazy — and medically inaccurate.

Myth: “Natural teeth are always safer than implants.”

Of course, keeping your natural teeth healthy is the gold standard. No argument there. But once a tooth is lost — due to decay, trauma, failed root canal, or other causes — the alternatives aren’t always better. Bridges require grinding down neighboring teeth. Partial dentures can lead to bone loss and shifting of other teeth. Doing nothing? That’s a fast track to bite collapse and joint issues.

Implants don’t carry zero risk, but when placed and maintained properly, they preserve more oral structure than most other replacement options. They’re not a downgrade from nature — they’re a sophisticated reconstruction strategy that’s backed by decades of success.

So why do these myths persist? Because fear travels faster than nuance. Because anecdotes feel more relatable than journal articles. And because in the absence of understanding, the mind fills in the gaps with the most emotionally gripping story — not the most plausible one.

Your best defense against myths isn’t just knowledge. It’s curated knowledge — the kind that filters claims through evidence, experience, and common sense. And you’ve just walked through quite a bit of it.

Next, we’ll explore what’s new on the horizon. Materials, methods, and innovations that continue to improve safety and outcomes in implantology — not because the old way was broken, but because the science keeps moving forward. Let’s look at what’s next.

Innovations in Implant Technology

Here’s something that often surprises people: dental implants, as dependable and established as they are, are still evolving. Rapidly. You might think that once we figured out how to anchor a titanium screw into bone and make it stay, that was the end of the story — job done, move on.

But dentistry doesn’t work like that. Medicine doesn’t work like that. Because as long as we’re still learning about biology — which, let’s be honest, is always — we’re also improving the tools we use to interact with it.

| Feature | Titanium | Zirconia |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Excellent | Excellent |

| Strength & durability | High (ductile, strong) | Good (brittle, less flexible) |

| Aesthetics (gum visibility) | Metallic hue may show | Tooth-colored, better for front teeth |

| Allergies or sensitivities | Rare (but possible) | Hypoallergenic |

| Long-term success data | Extensive (decades) | Emerging (less long-term data) |

| Corrosion risk | Minimal | None |

| Ideal use case | Most patients and sites | Aesthetic zones, metal-averse patients |

Implants are no exception. In fact, some of the latest advances are specifically designed to reduce the kind of long-term inflammation and micro-instability that could, in theory, open the door to more serious problems like cancer. Again, we’re not fixing a known failure point. We’re refining an already high-performing system to make it even safer, cleaner, and more adaptable.

Material matters — and it’s not just about titanium anymore

Titanium remains the gold standard, yes — for good reason. It’s strong, lightweight, and has an excellent track record of biocompatibility. But now, more manufacturers are pushing the boundaries of what titanium can be. We’re not talking about raw titanium rods anymore. We’re talking surface-modified implants with nano-scale topographies that actively encourage faster and stronger bone integration.

Some surfaces are treated to become more hydrophilic, meaning they attract moisture — and with it, blood, proteins, and healing cells. Others are micro-etched or plasma-sprayed to create topographies that mimic natural bone architecture. The goal isn’t just stability — it’s biological harmony.

Then there’s zirconia, the leading non-metal alternative. It’s white, which makes it ideal for aesthetic zones where metal might show through the gum. It’s also non-conductive and doesn’t corrode. Some patients — especially those with autoimmune issues or metal sensitivities — prefer zirconia for these reasons.

That said, zirconia comes with trade-offs. It’s more brittle than titanium, harder to adjust once placed, and historically had lower success rates. But new iterations, especially one-piece monolithic zirconia implants, are closing that gap. The field is watching closely.

The rise of digital planning and guided placement

Another major innovation? Precision. Not just in theory — in practice.

Digital workflows have changed the implant landscape. We’re talking 3D cone beam CT scans, intraoral scanning, and computer-aided design (CAD/CAM) software that allows for surgical guides with millimeter-level accuracy. That matters more than you might think.

Why? Because precise placement minimizes trauma to surrounding tissue. It avoids anatomical structures like nerves and sinuses. And it reduces the likelihood of micromovement — tiny, invisible shifts that can disrupt osseointegration or lead to long-term inflammation.

When an implant is placed exactly where the bone is strongest, at the correct depth, at the right angulation, it sets the stage for a smoother integration. Less inflammation. Fewer complications. And yes — theoretically — less chance of any long-term adverse biological response.

Coatings, bioactives, and the next frontier

Some of the most exciting innovations are happening at the microscopic level. We now have bioactive coatings — implant surfaces infused with agents like calcium phosphate, antimicrobial peptides, or growth factors that actively communicate with surrounding tissue. These coatings can speed healing, reduce bacterial colonization, and improve bone attachment.

There are even experimental materials being developed that release anti-inflammatory compounds slowly over time — like a built-in immune modulator.

And this is where the conversation about cancer gets a futuristic twist. If chronic inflammation is part of the theoretical risk chain, then implants that prevent inflammation at the cellular level may close that loop entirely. It’s not science fiction. These systems are already in clinical trials.

Smarter systems, not just smarter materials

It’s not just the hardware that’s improving. Implant systems today are modular, customizable, and increasingly designed with biological compatibility in mind. Platform switching — where the abutment is narrower than the implant collar — has been shown to reduce crestal bone loss and preserve soft tissue. That’s more than a structural win; it’s a biological one.

Some systems also incorporate antibacterial surfaces, designed not just to passively sit in the bone, but to defend it. We’re talking about passive protection against the bacteria that can cause peri-implantitis — one of the only truly common complications in implant dentistry.

And let’s not forget maintenance tech: ultrasonic scalers that don’t scratch implant surfaces, oral hygiene tools designed specifically for prosthetic contours, and AI-powered diagnostic imaging that can flag early bone changes before they’re visible to the naked eye.

So no, the world of implants isn’t standing still. And that’s the whole point: even with an already outstanding safety profile, researchers and clinicians continue to chase the margins — the 1% improvements, the rare complications, the long-tail outcomes.

That’s not because implants are dangerous. It’s because real medicine doesn’t settle. It iterates. It refines. It watches and learns. And in doing so, it makes already-safe treatments even safer, with a deeper understanding of how materials, biology, and time interact.

In the next section, we’ll zoom back out and tie all this together — not just what the science says, but how it intersects with personal risk, clinical practice, and your own decision-making process. Because by now, this isn’t just about whether implants cause cancer. It’s about how you carry what you’ve learned into the choices ahead.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Can dental implants cause cancer?

No, current scientific evidence does not support a causal relationship between dental implants and cancer. While rare cases of malignancies near implants have been reported, these are typically linked to other risk factors like smoking, pre-existing lesions, or chronic inflammation — not the implant itself.

2. Have any materials used in implants been shown to be carcinogenic?

Titanium, the most common implant material, is extensively studied and considered biocompatible. It is not classified as carcinogenic in humans. Zirconia, a metal-free alternative, also shows no evidence of carcinogenicity and is often used for patients with metal sensitivities.

3. What about long-term inflammation around implants — is that a cancer risk?

Chronic inflammation in any tissue can, in theory, increase cancer risk over time. That’s why managing peri-implant health is crucial. However, when implants are well maintained, the risk of chronic inflammation drops significantly.

4. Are there any warning signs I should watch for around my implant?

Yes. Persistent gum redness, bleeding, swelling, or ulcers that don’t heal should be evaluated promptly. These symptoms are more commonly associated with peri-implantitis or infection, but persistent issues deserve professional attention to rule out more serious pathology.

5. If I’ve had an implant for many years, should I be screened for cancer?

You should be screened anyway — not because of the implant, but because routine oral cancer screenings are part of good dental care, especially for adults over 40 or those with risk factors. Your dentist already performs this during regular exams.

6. Would choosing zirconia over titanium lower my cancer risk?

There’s no evidence to suggest that zirconia is safer from a cancer perspective. The choice between zirconia and titanium should be based on individual clinical needs, aesthetic preferences, and (rarely) confirmed allergies or sensitivities.

7. Are implants riskier than bridges or dentures?

All restorative options come with pros and cons. Implants tend to preserve bone better and don’t compromise adjacent teeth, but they require surgery and follow-up. Bridges and dentures don’t involve implantation but can introduce other long-term complications. None of these options are known to increase cancer risk.

8. I read that metal implants interfere with the body’s “energy fields.” Is that true?

This claim comes from alternative health theories and is not supported by scientific evidence. There’s no known biological mechanism by which titanium implants interfere with electromagnetic fields in a way that would influence health outcomes, let alone cause cancer.

9. How can I reduce my risk of complications after getting an implant?

Excellent oral hygiene, regular dental check-ups, avoiding tobacco, and managing systemic health conditions like diabetes all reduce your risk of implant complications — and by extension, any associated risks of chronic inflammation.

10. Is it still safe to get an implant if I have a family history of cancer?

Yes. A family history of cancer doesn’t contraindicate dental implants. Your dentist may take extra precautions during screening, but your inherited cancer risk is unrelated to implant safety.

Closing Thoughts

By now, you’ve seen the full picture. Not just the narrow question — “Can dental implants cause cancer?” — but the broader, more useful one: What do we actually know about risk, and how should we think about it?

The best health decisions are rarely about absolutes. They’re about context, evidence, and how those things intersect with your individual biology, your habits, and your priorities. This article wasn’t written to lull you into comfort or push a treatment plan. It was written to equip you — to arm you with facts, critical frameworks, and a more nuanced understanding of where real danger lies (and where it doesn’t).

Here’s what that understanding leaves us with:

Dental implants are among the most studied, refined, and biologically compatible technologies in modern restorative medicine. The overwhelming consensus — across disciplines, across continents — is that they do not cause cancer. Yes, tissue around them can become inflamed if neglected. Yes, rare lesions have been observed near implant sites. But zoom out, and the evidence is clear: there’s no causal relationship.

And more importantly: you’re not powerless in this equation. Your choices — to clean well, to check in regularly, to care about what’s happening in your body — carry far more weight than the composition of a small, inert fixture in your jawbone.

If anything, this whole exploration is a case study in how we should approach any health concern in today’s information landscape. With curiosity. With skepticism. With a willingness to ask the hard questions — but also to accept when those questions are met not with drama, but with data.

Because not every concern becomes a crisis. And not every “what if” becomes a headline. Sometimes, after all the reading, thinking, and worrying, you arrive at the answer that’s quietly reassuring:

You’re fine. The technology is sound. The risk is vanishingly small. And yes — you can smile, bite, chew, and live your life with confidence.

That’s not false comfort. That’s earned certainty.

And that, ultimately, is what modern medicine — and good journalism — are here to offer.