Can a Colonoscopy Detect Pancreatic Cancer? What You Need to Know

- What Does a Colonoscopy Actually Examine?

- Can Colonoscopy Reveal Early Clues of Pancreatic Cancer?

- Anatomical Proximity: Where the Colon and Pancreas Overlap

- Symptoms That May Be Misleading: When Pancreatic Cancer Mimics Colon Disease

- Early Detection Challenges: Why Pancreatic Cancer Often Goes Unnoticed

- What Imaging Tests Are Used After Colonoscopy When Cancer Is Still Suspected?

- Comparing Diagnostic Approaches: Colorectal vs. Pancreatic Cancer

- How Family History and Genetic Syndromes Influence Screening Strategy

- Interpreting Non-Colonic Symptoms in a Post-Colonoscopy Patient

- Diagnostic Bias: The Dangers of Reassurance After a Normal Colonoscopy

- When Colonoscopy Can Be Useful in Pancreatic Cancer Follow-Up

- Recognizing the Role of the Multidisciplinary Team

- Can Pancreatic Cancer Be Prevented Through Screening?

- Integrating Pancreatic Cancer Suspicion Into Clinical Workflow

- Why Early Diagnosis Matters and Why It’s Still So Rare

- What the Future Holds: AI, Biomarkers, and Integrated Diagnostics

- FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions About Colonoscopy and Pancreatic Cancer

What Does a Colonoscopy Actually Examine?

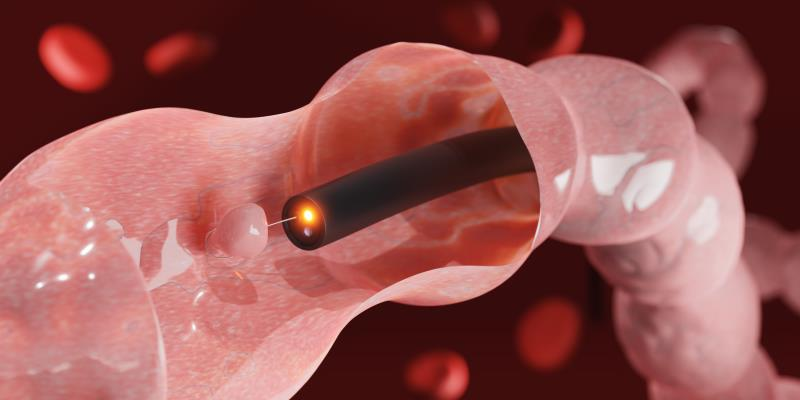

Colonoscopy is a procedure that allows direct visualization of the inner lining of the colon (large intestine) and the distal portion of the small intestine. A flexible tube with a camera, known as a colonoscope, is inserted through the rectum and advanced through the colon. This tool enables gastroenterologists to detect inflammation, ulcers, bleeding, polyps, tumors, and other structural abnormalities.

However, the colonoscope is limited to the lumen of the colon. It does not visualize organs outside the intestinal wall, such as the pancreas, liver, or gallbladder. Therefore, a colonoscopy cannot directly view or biopsy pancreatic tissue. That said, certain indirect signs might raise concern and prompt additional testing.

For example, if a tumor in the pancreas presses against the duodenum or causes secondary effects in the colon, such as unexplained narrowing or extrinsic compression, these findings may be incidentally noted during colonoscopy. But such observations are uncommon and nonspecific, requiring further imaging to confirm or rule out pancreatic involvement.

Can Colonoscopy Reveal Early Clues of Pancreatic Cancer?

Although colonoscopy is not designed to detect pancreatic cancer, it can sometimes pick up red flags that suggest the need for deeper investigation. One potential clue is a mass-like impression on the colon wall caused by an adjacent pancreatic tumor. This is more likely in cases where the tail of the pancreas, which lies near the splenic flexure, exerts external pressure.

Other subtle signs may include abnormal vascular patterns, unexplained colonic narrowing, or signs of gastrointestinal obstruction. While none of these findings confirm a diagnosis, they may be the first indication that something outside the colon is affecting bowel function.

Importantly, many symptoms of pancreatic cancer—such as bloating, constipation, fatigue, and early satiety—are nonspecific and may be present in benign conditions as well. That’s why incidental findings during colonoscopy are not enough. They must be supported by systemic markers of inflammation or malignancy, such as persistently elevated C-reactive protein levels. This is explored in more depth in our article on c reactive protein and cancer.

Anatomical Proximity: Where the Colon and Pancreas Overlap

Understanding the anatomy of the digestive system can clarify why colonoscopy is limited in evaluating the pancreas. The pancreas is a retroperitoneal organ, meaning it lies behind the peritoneum and is not in direct contact with the intestinal lumen. It is divided into the head, body, and tail, each of which neighbors different organs.

The head of the pancreas lies near the duodenum, which is part of the small intestine just before the colon. The tail of the pancreas is adjacent to the spleen and the splenic flexure of the colon. While these areas are physically close, they are separated by multiple tissue layers, making direct visualization during colonoscopy impossible.

In rare cases, advanced tumors of the pancreatic tail may invade the colon wall or cause visible deformities. In such scenarios, colonoscopy may capture signs of inflammation or erosion, but the underlying origin often remains unclear without cross-sectional imaging like CT or MRI.

Thus, while anatomical proximity makes secondary detection possible in extreme cases, colonoscopy is not a reliable screening tool for pancreatic cancer.

Symptoms That May Be Misleading: When Pancreatic Cancer Mimics Colon Disease

Pancreatic cancer is notoriously difficult to detect early because its symptoms overlap with many benign gastrointestinal conditions. Patients may report changes in bowel habits, bloating, gas, or vague abdominal pain—all of which are commonly attributed to colon disorders like IBS or diverticulosis.

Colonoscopy is often the first-line test in such scenarios, particularly if the patient is over 50 or has a family history of colon cancer. When the colonoscopy is normal but symptoms persist, clinicians must broaden the differential to include pancreatic, gastric, and biliary causes.

For example, a patient presenting with constipation and weight loss may have a completely normal colonoscopy but still harbor a tumor in the body of the pancreas that is compressing surrounding organs. Without additional imaging—such as an abdominal ultrasound, CT scan, or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)—this diagnosis could be missed.

Colonoscopy is an excellent test for identifying problems inside the colon. But when symptoms don’t align with findings, clinicians must consider adjacent organs and pursue appropriate diagnostics accordingly.

Early Detection Challenges: Why Pancreatic Cancer Often Goes Unnoticed

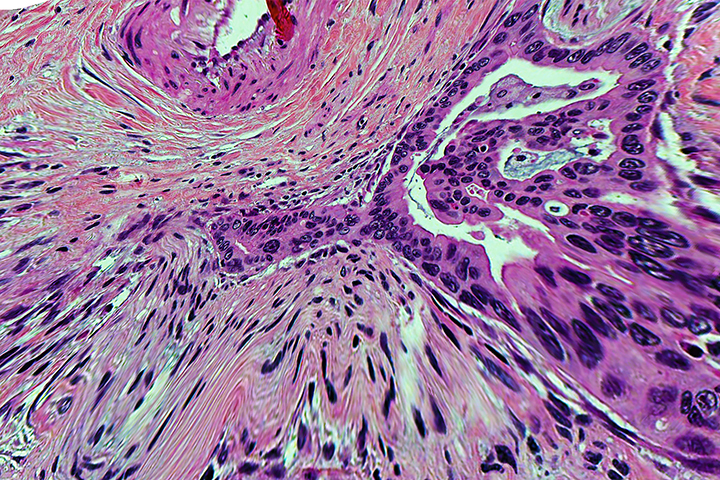

Pancreatic cancer is one of the most elusive malignancies in modern medicine. Its deep retroperitoneal location, lack of specific early symptoms, and rapid progression make it particularly difficult to catch at a curable stage. Unlike colorectal cancer, which can be detected through polyps or visible lesions during colonoscopy, pancreatic tumors often grow silently.

The disease typically presents late, when it has already invaded surrounding vessels or organs, limiting the options for surgical resection. The absence of a routine screening test for average-risk individuals further compounds the challenge. Even when patients undergo colonoscopy for abdominal symptoms, pancreatic cancer may be completely missed unless advanced imaging is pursued.

Clinicians rely heavily on a combination of high-risk profiles, tumor markers, and systemic clues. Inflammatory indicators like C-reactive protein (as discussed in the related article c reactive protein and cancer) are being investigated for earlier signal detection, though they are not yet sufficient to replace imaging or biopsy.

What Imaging Tests Are Used After Colonoscopy When Cancer Is Still Suspected?

When colonoscopy yields no significant findings but symptoms persist, the next logical step is cross-sectional imaging. CT (computed tomography) scans of the abdomen are often the first modality used due to their accessibility and ability to detect pancreatic masses, lymphadenopathy, ductal dilation, or liver metastases.

MRI is preferred for patients with contrast allergies or in cases where soft tissue resolution is critical—such as assessing small tumors or involvement of bile ducts. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), often paired with fine-needle aspiration (FNA), is increasingly the gold standard for detailed pancreatic evaluation and tissue sampling.

In advanced cases, PET-CT may be used to detect metabolically active lesions or distant metastasis. These imaging techniques provide much more diagnostic power than colonoscopy when it comes to evaluating suspected pancreatic cancer.

Comparing Diagnostic Approaches: Colorectal vs. Pancreatic Cancer

Below is a comparative summary that illustrates how diagnostic strategies differ based on the cancer type being investigated:

| Parameter | Colorectal Cancer | Pancreatic Cancer |

| Common Symptoms | Rectal bleeding, altered bowel habits | Vague pain, weight loss, jaundice, steatorrhea |

| Primary Screening Tool | Colonoscopy | No standard screening; imaging & labs used |

| First-line Imaging | CT or MRI for staging | CT, MRI, or EUS for mass detection |

| Tissue Diagnosis Method | Colonoscopic biopsy | EUS-guided FNA or surgical biopsy |

| Screening Population | Adults 45+, average risk | High-risk only (family history, genetic syndromes) |

| Detection Window | Early via polyps | Often late, asymptomatic progression |

The table highlights a major clinical gap: colorectal cancer has clearly defined pathways for screening and detection, while pancreatic cancer still lacks reliable early-detection methods—especially in asymptomatic individuals.

How Family History and Genetic Syndromes Influence Screening Strategy

While colonoscopy is recommended routinely for adults over 45, screening for pancreatic cancer is far more selective and primarily reserved for individuals with strong genetic predispositions. People with BRCA1/2 mutations, Lynch syndrome, or Peutz-Jeghers syndrome are known to be at increased risk.

In these populations, early and periodic imaging—usually via EUS or MRI—is considered even if symptoms are absent. Colonoscopy may still be part of the screening plan (especially in Lynch syndrome), but it plays no direct role in detecting pancreatic lesions.

Patients with both personal or family history of pancreatic and colon cancers may undergo dual-pathway screening protocols, which combine DEXA scans, tumor markers, and advanced imaging. Some of these cases also prompt research interest in immunoprevention models, like those described in the breast cancer vaccine 2025 article.

Interpreting Non-Colonic Symptoms in a Post-Colonoscopy Patient

When colonoscopy results are normal but a patient continues to experience GI symptoms like bloating, abdominal pain, or weight loss, physicians must look beyond the colon. This diagnostic challenge is where experience and a broad differential become critical. The pancreas, stomach, biliary tree, and even kidneys must be considered.

In patients over 60, or with a family history of gastrointestinal cancers, further evaluation should be prioritized, especially when symptoms evolve or systemic signs such as fatigue or nutrient deficiencies emerge. Even subtle laboratory abnormalities—like mild elevations in bilirubin or liver enzymes—may point toward a subclinical pancreatic disorder.

It’s essential to understand that a normal colonoscopy does not rule out serious disease. In fact, it often serves as a reminder that the underlying cause may be hidden deeper within the abdominal cavity, particularly when the pancreas is involved.

Diagnostic Bias: The Dangers of Reassurance After a Normal Colonoscopy

A common clinical pitfall is premature reassurance after a normal colonoscopy. Patients and even providers may falsely assume that all serious pathology has been ruled out, delaying further testing. This is especially risky when the presenting symptoms are not specific to the colon.

Pancreatic cancer is often missed this way. If the patient’s fatigue, abdominal discomfort, or unintended weight loss persists, deeper imaging is warranted. Further workup should include a full abdominal CT or MRI, and possibly EUS—particularly if blood tests show anemia, elevated CRP, or abnormal liver function.

This lesson also applies to other diagnostic tools. For example, as described in the article can a bone density test detect cancer, even tests designed for non-cancer purposes can produce findings that prompt deeper oncologic evaluation. The key is pattern recognition, not overreliance on a single modality.

When Colonoscopy Can Be Useful in Pancreatic Cancer Follow-Up

While colonoscopy is not helpful for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, it does have a role in long-term surveillance in selected patients. For example, those who have received radiation near the abdominal midline, or underwent surgical resections involving adjacent structures, may develop colonic complications over time.

Additionally, patients treated with chemotherapy or targeted agents may be at risk of gastrointestinal side effects that mimic or mask colonic disease. In these cases, colonoscopy can help distinguish between treatment-related colitis, secondary tumors, and unrelated polyps—especially important in long-term survivorship.

Furthermore, individuals with hereditary cancer syndromes often require both upper GI and colon surveillance. In such cases, colonoscopy may be coordinated with other imaging studies to minimize risk and optimize detection.

Recognizing the Role of the Multidisciplinary Team

Diagnosing and managing pancreatic cancer requires collaboration between multiple specialties. Gastroenterologists, radiologists, oncologists, pathologists, surgeons, and primary care providers must all work together to ensure no sign is overlooked.

Gastroenterologists provide initial evaluation and rule out colonic pathology. Radiologists interpret subtle pancreatic changes, while oncologists and surgeons coordinate staging and treatment. Primary care physicians help monitor systemic symptoms and advocate for timely referrals.

This collaboration becomes essential when symptoms are non-specific and initial tests are inconclusive. It’s also key in post-treatment surveillance, where shared decision-making can prevent recurrence from being missed due to assumptions that one “clear” test was enough.

Can Pancreatic Cancer Be Prevented Through Screening?

Unlike colorectal cancer, where colonoscopy provides an opportunity to remove precancerous polyps, pancreatic cancer lacks a clear preinvasive stage that can be screened or treated preventively in the general population. Its biology is more aggressive, and its progression often silent—meaning by the time symptoms arise, curative options are limited.

However, for individuals with a strong family history or known genetic mutations (BRCA1/2, CDKN2A, STK11, PRSS1), screening may help. Current recommendations suggest the use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or MRI/MRCP in high-risk individuals beginning at age 50—or 10 years earlier than the youngest affected relative.

While colonoscopy is not part of pancreatic screening, it remains vital in patients with dual risk (e.g., those with Lynch syndrome). Prevention in pancreatic cancer relies heavily on risk stratification, genetic counseling, and early imaging—not endoscopy alone.

Integrating Pancreatic Cancer Suspicion Into Clinical Workflow

In modern clinical practice, diagnostic decision-making is increasingly algorithmic—but real-world symptoms often don’t follow algorithms. When a patient has vague GI complaints and a normal colonoscopy, clinicians must look beyond checklists.

A practical approach includes checking inflammatory and tumor markers (such as CRP, CA 19-9), reviewing medication history, and considering imaging even in the absence of classic signs. This proactive thinking shortens diagnostic delays and may uncover disease at an earlier, more manageable stage.

Incorporating alerts in electronic health records—based on symptoms, family history, or lab patterns—can help flag patients who may need additional imaging. Colonoscopy reports should include guidance when findings are negative but symptoms persist, reminding clinicians not to stop with “normal.”

Why Early Diagnosis Matters and Why It’s Still So Rare

Pancreatic cancer survival depends almost entirely on the stage at diagnosis. Patients diagnosed at Stage I have a 5-year survival rate exceeding 35%, while those diagnosed at Stage IV have less than 5%. Unfortunately, over 80% of cases are found after local advancement or metastasis.

The pancreas’s anatomical position behind the stomach and its lack of early pain receptors make tumors less likely to be felt or seen until they compress neighboring structures. Even imaging can miss small tumors if not targeted correctly or performed early enough.

This makes patient persistence—and clinician suspicion—critical. If a patient returns multiple times with unexplained GI symptoms and all routine tests are normal, escalating to higher-level diagnostics is not just reasonable, but necessary.

What the Future Holds: AI, Biomarkers, and Integrated Diagnostics

Looking forward, the key to early pancreatic cancer detection may lie in advanced blood biomarkers, artificial intelligence, and integrated diagnostic platforms. Researchers are developing liquid biopsies that detect circulating tumor DNA or exosomes long before a tumor is visible on imaging.

AI-powered algorithms can now analyze patterns in lab values, imaging, and even symptom language in electronic records to identify at-risk patients early. These systems will not replace colonoscopy or imaging but will work alongside them to flag concerns earlier.

In time, routine diagnostics like colonoscopy may include adjunct tools—such as breath analysis or micro-sensor detection—that expand their relevance beyond the colon itself. Until then, awareness and clinical vigilance remain the most powerful tools we have.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions About Colonoscopy and Pancreatic Cancer

Can a colonoscopy detect pancreatic cancer directly?

No. Colonoscopy is designed to evaluate the colon and rectum, not the pancreas. Since the pancreas lies outside the intestinal lumen, it cannot be visualized directly during the procedure. However, secondary signs like extrinsic compression or unexplained narrowing of the colon may raise suspicion.

Why is pancreatic cancer sometimes missed despite a normal colonoscopy?

Pancreatic cancer often causes vague, non-specific symptoms that overlap with common colon conditions. If colonoscopy is clear but symptoms persist—such as weight loss, back pain, or digestive changes—further imaging is essential. A normal colonoscopy does not rule out pancreatic disease.

What symptoms might indicate pancreatic cancer even after a normal colonoscopy?

Persistent upper abdominal pain, jaundice, greasy stools, unintentional weight loss, or new-onset diabetes may all point to pancreatic issues. These symptoms should prompt further evaluation with imaging studies, not reassurance based solely on colonoscopy results.

Can colonoscopy reveal indirect signs of pancreatic cancer?

Rarely, yes. If a tumor in the pancreatic tail or head causes external pressure on nearby segments of the colon, it may cause visible indentations or strictures during colonoscopy. These findings are non-specific and require CT or MRI follow-up.

Is it common for pancreatic cancer to coexist with colon cancer?

It’s uncommon but possible, particularly in patients with hereditary cancer syndromes like Lynch syndrome. These individuals require vigilant screening for both cancers using colonoscopy, MRI, and sometimes endoscopic ultrasound.

What imaging tests are used to detect pancreatic cancer after a normal colonoscopy?

CT scans and MRIs are commonly used first. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provides higher sensitivity and can guide biopsy. PET scans may be used to assess metastasis. These modalities complement—not replace—initial endoscopy.

How quickly can pancreatic cancer progress after a clean colonoscopy?

Pancreatic cancer can develop and grow silently, often progressing rapidly. It’s possible for symptoms to emerge within months after a normal colonoscopy if the tumor arises in the pancreas. That’s why new symptoms should never be dismissed, regardless of recent test results.

Can blood tests help detect pancreatic cancer if colonoscopy is normal?

Yes. CA 19-9, liver function tests, and inflammatory markers like CRP may support further investigation. As detailed in the article c reactive protein and cancer, inflammation can sometimes reflect underlying malignancy.

Does colonoscopy have any value in pancreatic cancer management?

Indirectly, yes. It helps rule out other GI pathologies and may identify colonic changes due to external tumor compression or treatment side effects. In some cases, it’s used in long-term surveillance of patients with hereditary risk.

What is the risk of delaying pancreatic cancer diagnosis after normal colonoscopy?

The risk is significant. Because pancreatic cancer is aggressive, any delay in diagnosis shortens the window for curative surgery. Persistent symptoms must be taken seriously, even if prior endoscopy was unremarkable.

What role do tumor markers like CA 19-9 play?

CA 19-9 is elevated in most pancreatic cancers, though not all. It’s not a screening test, but rising values—especially with symptoms—can guide diagnosis and treatment monitoring. It’s best used alongside imaging and clinical judgment.

Is pancreatic cancer screening available for the general public?

Not currently. Screening is limited to high-risk individuals with genetic predisposition or strong family history. For most people, screening is done on a case-by-case basis when symptoms suggest further investigation.

Can colonoscopy be used to follow up after pancreatic cancer treatment?

Yes, particularly if radiation or surgery affected nearby parts of the colon. It can help detect late complications like strictures or polyps that may arise due to therapy.

What are the most effective ways to detect pancreatic cancer early?

In high-risk individuals, MRI and EUS are most effective. In the general population, there’s no proven screening test. Early detection relies on recognizing symptoms and risk factors, and acting promptly when imaging is needed.

Are there diagnostic overlaps with other tools like bone scans or DEXA?

There can be. As discussed in the article can a bone density test detect cancer, some cancers affect bone structure and may be detected incidentally during unrelated screening. Similarly, non-GI tests may raise red flags that prompt deeper oncologic workups.