C-Reactive Protein and Cancer: Understanding the Hidden Inflammatory Link

- What Is C-Reactive Protein and Why Does It Matter?

- How CRP Levels Correlate with Cancer Development

- Symptoms and Conditions That May Cause Elevated CRP in Cancer Patients

- CRP as a Prognostic Tool: What the Evidence Shows

- Can CRP Be Used to Monitor Treatment Response?

- Comparing CRP Levels Across Different Cancer Types

- How CRP Interacts with the Immune System in Cancer

- Factors Other Than Cancer That May Elevate CRP

- Is High CRP a Cause or a Consequence of Cancer?

- CRP and Cancer-Related Fatigue: The Missing Link?

- The Role of CRP in Palliative Oncology

- How CRP Is Being Integrated into Personalized Cancer Care

- Can C-Reactive Protein Be Lowered to Improve Outcomes?

- Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Managing Inflammation

- The Future of CRP in Cancer Research and Drug Development

- CRP in Relation to Other Cancer Biomarkers

- FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions About C-Reactive Protein and Cancer

What Is C-Reactive Protein and Why Does It Matter?

C-reactive protein is an acute-phase protein synthesized by the liver when inflammation is present anywhere in the body. It plays a role in the innate immune response, helping to mark damaged or infected cells for clearance by white blood cells. While a useful tool for identifying infections, CRP is nonspecific—it doesn’t tell you what the cause is, only that inflammation is occurring.

In the context of cancer, CRP is gaining attention for its ability to reflect tumor-associated inflammation. Tumors often create a pro-inflammatory environment that supports growth, blood vessel formation, and immune evasion. CRP may be elevated not just due to the cancer itself, but also in response to tissue damage from surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation.

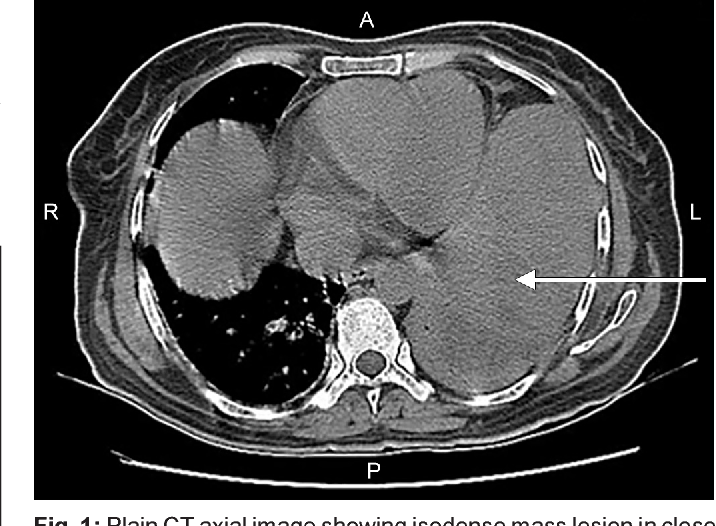

High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) tests can detect subtle elevations and are particularly useful in oncology. Persistent high CRP levels have been associated with worse outcomes in various cancers, including colorectal, lung, and breast cancers—especially in those with advanced or metastatic disease. For example, in patients with breast cancer metastasis to liver, sustained CRP elevation often reflects aggressive systemic inflammation, indicating a more challenging disease course.

How CRP Levels Correlate with Cancer Development

Inflammation is a well-recognized hallmark of cancer, and CRP is one of its most accessible markers. Chronic inflammatory conditions—such as hepatitis, pancreatitis, or inflammatory bowel disease—can predispose individuals to cancer due to prolonged cellular stress and DNA damage. In this context, CRP becomes a signal of ongoing immune activation that may eventually facilitate tumorigenesis.

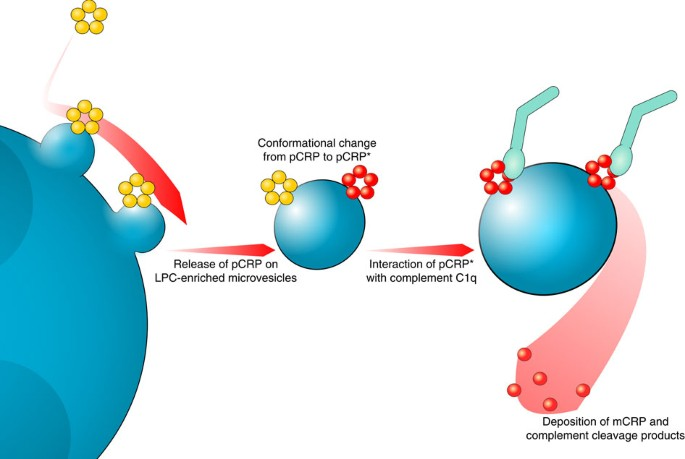

Cancer cells themselves contribute to CRP elevation by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6), which stimulate the liver to produce CRP. This dynamic creates a feedback loop: more cancer growth leads to more inflammation, which in turn fuels further progression. In patients with early-stage disease, mildly elevated CRP may be the first clue to a silent malignancy, especially in those with no infection or autoimmune disease.

Notably, CRP is not a diagnostic tool for cancer, but when viewed alongside other markers—like imaging, tumor-specific antigens, or biopsies—it can support a broader diagnostic picture. Its predictive role is becoming especially valuable in patients with vague symptoms but unexplained inflammation.

Symptoms and Conditions That May Cause Elevated CRP in Cancer Patients

Cancer patients may present with a wide range of symptoms, many of which overlap with those caused by elevated CRP. These can include fatigue, fever, weight loss, and generalized malaise—symptoms commonly associated with both inflammation and tumor burden. Understanding whether CRP is elevated due to infection, cancer progression, or treatment response becomes a crucial clinical decision point.

Surgery, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy can all transiently increase CRP levels, particularly if there is tissue damage, infection, or an overactive immune response. For instance, in patients undergoing tumor resection, CRP may spike in the postoperative period but should gradually decline. If it doesn’t, it could indicate complications like infection or incomplete tumor removal.

In palliative settings, persistently high CRP is often linked with cachexia (cancer-related wasting), systemic immune activation, or poor overall prognosis. Recognizing these patterns helps clinicians anticipate complications and adjust treatment accordingly.

CRP as a Prognostic Tool: What the Evidence Shows

Numerous studies have shown that elevated CRP levels are associated with poorer outcomes across various cancer types. In breast, lung, gastrointestinal, and even gynecological cancers, patients with high CRP tend to have shorter progression-free and overall survival. This association remains even when adjusted for other variables like tumor size, stage, and treatment modality.

The reason for this strong correlation lies in how inflammation affects tumor behavior. CRP doesn’t cause cancer directly, but it reflects an underlying biological environment where cancer is more likely to thrive. High CRP levels suggest a pro-tumor state: increased angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and resistance to apoptosis.

Some oncologists are beginning to incorporate CRP into routine cancer assessments, particularly in advanced stages where it helps refine prognosis and treatment planning. For instance, patients with multiple metastases and persistently high CRP may be directed toward supportive care earlier, improving comfort and resource allocation.

Can CRP Be Used to Monitor Treatment Response?

Yes, and it’s becoming more common. During treatment, especially in metastatic or inflammatory cancers, oncologists monitor CRP levels as a way to assess how the disease is responding. A falling CRP level often signals that inflammation is decreasing—either due to tumor shrinkage or effective immunomodulation. Conversely, rising CRP levels during therapy may point to resistance, progression, or complications such as infection.

CRP can also help distinguish between true disease progression and pseudoprogression, especially in patients receiving immunotherapy. In those cases, an initial spike in inflammation may occur as immune cells flood the tumor site. When tracked alongside imaging and clinical signs, CRP offers a useful window into what’s really happening inside the patient’s body.

That said, it is important not to rely solely on CRP. It should be interpreted in context with full lab panels, radiologic findings, and patient-reported symptoms. It is a piece of the puzzle—not the whole picture.

Comparing CRP Levels Across Different Cancer Types

To illustrate how CRP values vary across malignancies and clinical states, here’s a comparative table based on recent data:

| Cancer Type | Typical CRP Range (mg/L) | When Elevated | Prognostic Significance |

| Breast Cancer | <5–15 | Post-op, advanced or metastatic stages | Higher CRP = worse survival |

| Lung Cancer | >20 | At diagnosis and during disease flare | Strong predictor of early progression |

| Colorectal Cancer | 10–30 | Recurrence or liver metastasis | Correlates with stage and recurrence risk |

| Pancreatic Cancer | >30 | Even at early stage | Very poor prognosis when CRP is high |

| Ovarian Cancer | 10–25 | Chemotherapy resistance | Indicates treatment failure |

As shown, the cut-off values differ depending on tumor biology and stage. Some cancers inherently create more inflammation, while others show subtle increases. This makes CRP a highly dynamic marker rather than a binary one.

How CRP Interacts with the Immune System in Cancer

CRP doesn’t just passively reflect inflammation—it plays an active role in immune modulation. It can bind to dead or dying cells, attract immune cells to tumor sites, and influence how aggressively the immune system responds. While this might sound beneficial, in the tumor microenvironment, this mechanism can be hijacked.

Cancer cells often release inflammatory signals that draw CRP-producing liver responses, indirectly protecting the tumor by masking it or encouraging pro-tumor immune phenotypes. Elevated CRP is also associated with increased levels of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which actively inhibit anti-cancer immune responses.

Understanding this interaction has spurred interest in combining immunotherapy with inflammation-modulating agents. New strategies—like checkpoint inhibitors paired with IL-6 blockers—are designed to reduce CRP-related immune suppression. This approach mirrors some of the advances made in immune-oncology, such as those shaping the breast cancer vaccine 2025, where immune stimulation is being fine-tuned for precision and safety.

Factors Other Than Cancer That May Elevate CRP

Not every high CRP level means cancer is worsening. CRP is a general inflammatory marker and can be elevated for many other reasons. Infections, autoimmune diseases like lupus or rheumatoid arthritis, obesity, recent surgeries, trauma, and even smoking can all increase CRP levels.

For cancer patients, this can create diagnostic confusion. For instance, a patient undergoing chemotherapy who develops an infection will likely have a CRP spike—but that doesn’t necessarily mean tumor growth. Similarly, someone recovering from surgery or radiation may have prolonged CRP elevation that resolves with time.

That’s why serial measurements and trend tracking are essential. A one-time high CRP reading is far less meaningful than a pattern over weeks or months. Clinicians must always take into account timing, context, and comorbid conditions when interpreting the results.

Is High CRP a Cause or a Consequence of Cancer?

This is one of the most debated questions in oncology. While elevated CRP levels clearly correlate with poor outcomes, whether they are simply a consequence of tumor-driven inflammation or actively contribute to cancer progression remains under investigation.

Some studies suggest that CRP, as part of the broader inflammatory cascade, may directly influence tumor behavior. Chronic inflammation can lead to DNA damage, disrupt cellular repair, and suppress anti-tumor immunity—all mechanisms that aid cancer development. Therefore, while CRP itself may not initiate cancer, the environment it reflects (and possibly reinforces) is highly permissive to malignancy.

Other research supports the idea that CRP is primarily a consequence—a marker of the systemic inflammation created by tumors. It’s not that CRP causes cancer to spread, but that its presence signals a state where cancer is already flourishing. For instance, patients with breast cancer metastasis to skin often show persistently elevated CRP levels due to widespread inflammatory activity in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

In either case, CRP remains an important clinical clue and a potential therapeutic target in cancer management.

CRP and Cancer-Related Fatigue: The Missing Link?

Fatigue is one of the most debilitating symptoms experienced by cancer patients, and its cause has long puzzled clinicians. While anemia, poor nutrition, and emotional distress play a role, systemic inflammation—reflected by elevated CRP—may be a key driver.

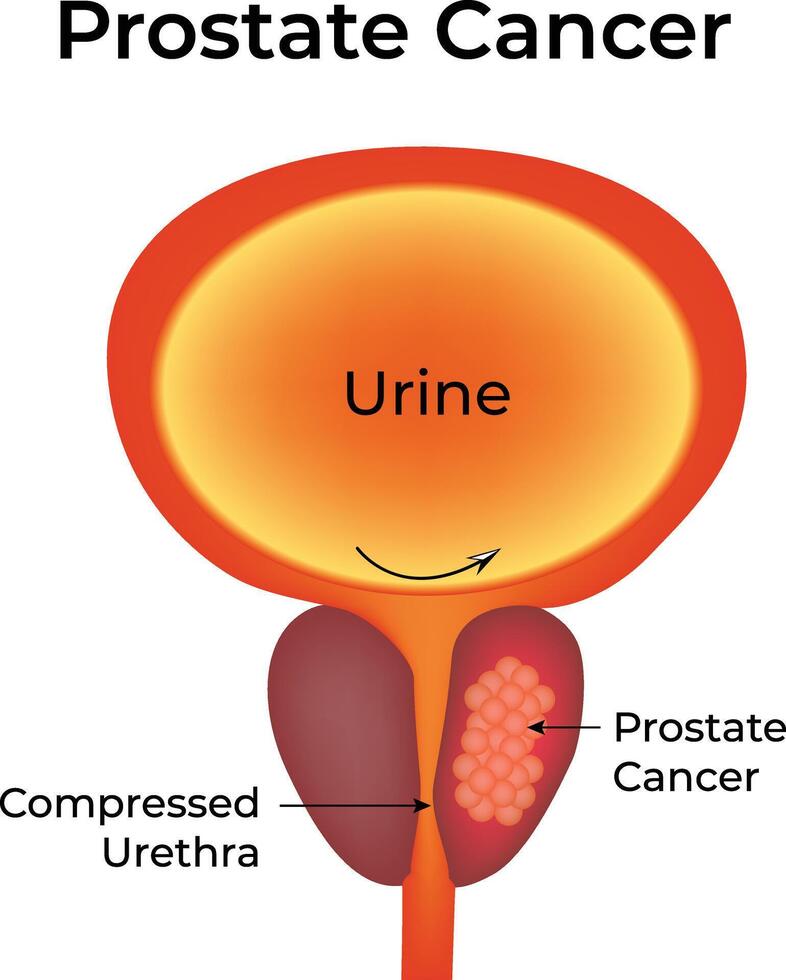

High CRP levels have been correlated with increased fatigue in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer patients, regardless of disease stage. This suggests that the inflammatory response itself may be altering central nervous system signaling, leading to a profound sense of tiredness that is not relieved by rest.

Recognizing this connection has therapeutic value. Anti-inflammatory interventions—ranging from corticosteroids to dietary modifications and exercise—may help alleviate fatigue by reducing CRP levels. Clinicians are increasingly integrating inflammation management into holistic cancer care to improve quality of life, not just survival.

The Role of CRP in Palliative Oncology

In the palliative care setting, CRP serves as both a biomarker and a prognostic tool. Patients with persistently elevated CRP—especially in the absence of infection—often have shorter survival times and more rapid clinical decline. It becomes a marker not only of disease severity but of systemic breakdown.

For example, a rising CRP in a patient with stable imaging may still prompt a shift in treatment goals—from aggressive intervention to comfort-focused care. It also helps in end-of-life planning, as families and care teams navigate complex decisions about nutrition, hospitalization, and symptom control.

In this context, CRP allows oncologists to act with greater foresight. Rather than reacting to visible deterioration, they can proactively initiate support services, counseling, and palliative measures based on inflammatory trends.

How CRP Is Being Integrated into Personalized Cancer Care

As oncology shifts toward personalized medicine, CRP is joining the list of accessible, actionable biomarkers that guide treatment. Oncologists now track CRP not only as a sign of active disease but as a factor in decision-making—when to scan, when to modify therapy, and when to consult supportive care.

Some treatment algorithms now include CRP as part of risk stratification models. For example, in patients with early-stage cancer and high baseline CRP, closer monitoring and more aggressive follow-up may be justified. Conversely, a stable or declining CRP in a metastatic patient might support continued treatment or reduced imaging frequency.

CRP is also used alongside genomic data, patient history, and immune profiling to tailor regimens. It may influence eligibility for clinical trials, particularly those testing inflammation-modulating agents or novel immunotherapies.

Can C-Reactive Protein Be Lowered to Improve Outcomes?

This question remains an area of active research. While CRP is widely used as a marker of inflammation, scientists are now exploring whether deliberately lowering CRP or targeting its upstream drivers can directly impact cancer outcomes. Preliminary evidence suggests that it may be possible.

Drugs such as NSAIDs, corticosteroids, statins, and IL-6 inhibitors have shown the ability to reduce CRP levels in cancer patients. In particular, IL-6 blockade has been investigated in conjunction with immunotherapy to potentially improve treatment response. Lifestyle factors—such as regular physical activity, weight loss, smoking cessation, and anti-inflammatory diets—have also been linked to reduced baseline CRP levels in cancer survivors.

Still, it’s not clear whether reducing CRP itself leads to longer survival or whether it’s simply a byproduct of better overall health. As such, clinicians currently focus on treating the underlying cause of inflammation (e.g., infection, tumor burden) rather than CRP in isolation.

Complementary and Alternative Approaches to Managing Inflammation

In integrative oncology, a growing number of patients seek out alternative or adjunctive therapies to reduce systemic inflammation and, by extension, CRP levels. While these approaches are not substitutes for evidence-based cancer treatment, they may offer symptom relief and immune support.

Popular strategies include omega-3 fatty acids, turmeric (curcumin), green tea polyphenols, and medicinal mushrooms like reishi or maitake. Some patients also explore acupuncture, massage, or yoga to reduce stress-related inflammatory responses. These modalities are generally safe when supervised and may help address cancer-related fatigue, pain, or anxiety—all of which indirectly influence inflammation.

However, the evidence base remains uneven. Patients should consult their oncologist or a certified integrative medicine specialist before starting any new regimen. The goal is not to replace conventional therapy, but to support the body’s resilience and recovery throughout the cancer journey.

The Future of CRP in Cancer Research and Drug Development

CRP is now being investigated not just as a marker, but as a therapeutic target. Researchers are exploring how interrupting CRP pathways or blocking its upstream activators might alter tumor behavior, improve immune response, or reduce treatment resistance.

Clinical trials are underway testing combinations of immunotherapy with IL-6 inhibitors or JAK/STAT blockers—pathways closely tied to CRP production. These efforts aim to turn down the “volume” of cancer-related inflammation, which in turn may make tumors more vulnerable to immune attack or less likely to metastasize.

Other innovations include CRP-integrated diagnostic models that combine genetic, proteomic, and imaging data to offer real-time insights into cancer status. Artificial intelligence systems are already being trained to predict outcomes using CRP curves and other biomarkers in complex clinical settings.

As our understanding of inflammation in cancer deepens, CRP will likely play an even more central role in personalized medicine, treatment selection, and dynamic care strategies.

CRP in Relation to Other Cancer Biomarkers

While CRP is useful, it is not a standalone tool. Its value increases when interpreted alongside other cancer biomarkers like CA 15-3, CA 125, PSA, or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). Each provides a different perspective on tumor activity, progression risk, or treatment response.

For example, in breast cancer, combining CRP with CA 15-3 levels and imaging results may give a more complete picture of disease dynamics. In colorectal or ovarian cancers, CRP trends may complement tumor markers to identify recurrence early.

Clinicians are now layering biomarker profiles to guide precision oncology, adjusting treatments in real time based on how these markers evolve. CRP’s affordability, rapid availability, and sensitivity to inflammatory changes make it a natural companion to more specialized tests—offering both clinical context and actionable insight.

FAQ – Frequently Asked Questions About C-Reactive Protein and Cancer

What is C-reactive protein (CRP) and how is it linked to cancer?

CRP is a protein produced by the liver in response to inflammation. In cancer, elevated CRP levels often indicate the presence of tumor-related inflammation, which may reflect aggressive growth, immune suppression, or treatment complications. It’s not a cancer marker per se, but it provides important context about the body’s inflammatory state.

Can CRP be used to detect cancer early?

CRP alone is not specific enough to detect cancer early. However, when elevated without a clear cause (like infection or injury), it may prompt further investigation, especially if paired with symptoms or risk factors. It’s more commonly used to monitor cancer progression or treatment response.

Why would CRP be high in a cancer patient without infection?

Cancer itself can provoke systemic inflammation. Tumors release cytokines like IL-6 that stimulate the liver to produce CRP. High CRP without infection may signal tumor progression, recurrence, or immune-related changes. In some cases, it may also reflect hidden metastasis or treatment resistance.

Is a high CRP level always bad for cancer patients?

Not always. A temporary increase after surgery or treatment can be normal. What matters more is the trend over time. Persistently high or rising CRP may suggest complications, while a declining CRP level during therapy often correlates with improved outcomes.

What types of cancer are most associated with high CRP levels?

Cancers with high systemic inflammation, such as lung, pancreatic, colorectal, and advanced breast cancers, often show elevated CRP levels. For example, patients with breast cancer metastasis to liver frequently exhibit high CRP due to both liver involvement and systemic immune activation.

Can CRP levels help guide cancer treatment decisions?

Yes. Oncologists may use CRP to monitor treatment efficacy or to flag complications. In advanced cases, CRP trends can help determine when to adjust or stop therapy, especially when combined with imaging and tumor markers.

Does chemotherapy affect CRP levels?

Yes. Chemotherapy can raise CRP due to tissue damage or secondary infections. A CRP spike is common post-infusion, but should normalize as inflammation subsides. Persistently high levels may prompt evaluation for infection, tumor progression, or drug toxicity.

Can CRP levels predict recurrence in cancer survivors?

Elevated CRP after remission may be an early indicator of recurrence, though it’s not definitive. Many survivors undergo regular CRP checks alongside imaging and tumor markers. Rising CRP without another explanation warrants closer follow-up.

How does CRP relate to cancer-related fatigue?

Inflammation is a key contributor to fatigue. High CRP levels have been linked to persistent tiredness, even in patients with stable disease. Managing inflammation through medications, diet, or lifestyle changes may help relieve fatigue and improve daily function.

Is CRP useful in immunotherapy monitoring?

Yes, especially in distinguishing between immune-related effects and true disease progression. For instance, CRP may temporarily rise during immune activation. Paired with imaging, CRP helps clinicians interpret complex treatment responses, particularly in patients receiving new options like the breast cancer vaccine 2025.

Can alternative therapies reduce CRP levels in cancer patients?

Some integrative approaches—like omega-3 supplementation, anti-inflammatory diets, and moderate exercise—may reduce CRP. These are not substitutes for medical treatment, but can support systemic health and recovery, especially in survivors or patients in remission.

What are normal CRP levels, and when should I worry?

In healthy adults, CRP levels are typically below 5 mg/L. Levels above 10 mg/L suggest active inflammation, while those exceeding 30–50 mg/L are considered significantly elevated. Persistent or unexplained elevation should be investigated further.

Is it possible to lower CRP through medication?

Yes. NSAIDs, corticosteroids, statins, and IL-6 inhibitors can reduce CRP. However, these are used selectively in oncology, depending on the cancer type, symptoms, and risk of side effects. They may be combined with other treatments to manage inflammation.

Does CRP play a role in skin-related cancer complications?

Absolutely. Patients with inflammatory lesions or dermal involvement—such as those with breast cancer metastasis to skin—often show localized and systemic CRP elevation. This can help guide wound care, assess progression, and inform pain management.

Can CRP be part of long-term cancer monitoring?

Yes. Many oncologists now include CRP in follow-up panels. It’s easy to measure, inexpensive, and provides insight into inflammation trends, treatment effects, and overall disease trajectory—especially when interpreted with other clinical data.