Bladder Cancer in Dogs: Recognizing Symptoms and Ensuring Early Intervention

- What Is Bladder Cancer in Dogs?

- Which Breeds Are Most Commonly Affected?

- How Bladder Cancer Develops in Canines

- Early Warning Signs: Symptoms Every Dog Owner Should Know

- Why Bladder Cancer Symptoms Are Often Misdiagnosed

- Diagnostic Tests Used to Identify Bladder Cancer in Dogs

- Comparing Canine and Feline Bladder Cancer Presentations

- How Tumor Location Affects Symptoms and Outcomes

- What Role Does the Prostate Play in Male Dogs With Bladder Cancer?

- Treatment Options for Bladder Cancer in Dogs

- Understanding the Prognosis and Life Expectancy

- Nutritional Support and Home Care for Affected Dogs

- Environmental and Lifestyle Factors That May Increase Risk

- Monitoring and Follow-Up: What Happens After Diagnosis?

- Bladder Cancer Symptoms vs. Other Conditions

- Key Takeaways for Dog Owners Facing a Bladder Cancer Diagnosis

- FAQ

What Is Bladder Cancer in Dogs?

Bladder cancer in dogs refers primarily to transitional cell carcinoma (TCC), a malignant tumor that develops in the lining of the bladder. This cancer type is known for its aggressive local invasion into the bladder wall and surrounding tissues, which can eventually obstruct the urinary tract and cause systemic complications. While bladder tumors are relatively rare, accounting for less than 2% of all canine cancers, they can be life-threatening if left undetected.

TCC is more frequently diagnosed in middle-aged to senior dogs, with certain breeds showing a higher predisposition. Understanding what bladder cancer is—and more importantly, how it behaves—helps owners become vigilant about symptoms that might otherwise be attributed to simple urinary tract infections or age-related issues.

Which Breeds Are Most Commonly Affected?

Certain dog breeds have a notably higher risk of developing bladder cancer, particularly TCC. Among the most affected are:

- Scottish Terriers (the highest risk group)

- Shetland Sheepdogs

- Beagles

- West Highland White Terriers

- Wire Fox Terriers

The reasons for this predisposition are believed to include genetic susceptibility, as well as environmental exposures that may disproportionately affect some breeds based on size and lifestyle. Dogs in these higher-risk groups should be monitored more closely for urinary symptoms, especially as they age.

In addition to breed, female dogs and neutered males have shown slightly increased rates of diagnosis. This highlights the importance of individualized risk assessments in veterinary practice when evaluating chronic urinary signs in predisposed pets.

How Bladder Cancer Develops in Canines

The development of bladder cancer in dogs is a multifactorial process involving genetic mutations, chronic inflammation, and likely environmental carcinogens. Exposure to certain herbicides, pesticides, and industrial chemicals has been implicated in some studies, especially in dogs who spend time on chemically treated lawns or urban settings with environmental toxins.

TCC arises from the transitional epithelial cells lining the inside of the bladder. Over time, abnormal cellular growth leads to tumor formation, which begins locally but may expand outward into the bladder wall, urethra, prostate (in males), and even lymph nodes or lungs if metastasis occurs.

In its early stages, the disease may remain silent or mimic minor urinary tract issues. This underscores why routine exams and attention to subtle changes in urinary behavior are essential.

Early Warning Signs: Symptoms Every Dog Owner Should Know

Bladder cancer symptoms often resemble those of urinary tract infections (UTIs), which can delay diagnosis. However, certain signs are persistent and escalate over time, suggesting something more serious may be occurring. The most common early symptoms include:

- Blood in the urine (hematuria), often intermittent

- Straining to urinate (stranguria) or frequent attempts with little output

- Increased frequency of urination (pollakiuria)

- Incontinence or urine dribbling, particularly if the tumor is affecting the urethra

As the tumor grows or spreads, additional symptoms may emerge:

- Lethargy

- Decreased appetite

- Abdominal discomfort or swelling

- Weight loss

- Painful urination accompanied by vocalizing

Recognizing these signs early and conveying them clearly to a veterinarian can significantly improve the odds of timely diagnosis and effective management.

Why Bladder Cancer Symptoms Are Often Misdiagnosed

Bladder cancer in dogs is frequently misdiagnosed as a urinary tract infection (UTI), especially in the early stages when symptoms are mild or intermittent. Since both conditions present with similar signs—like straining, blood in urine, and increased frequency—veterinarians often start with antibiotics and symptom management.

The problem arises when the symptoms don’t improve with treatment, or quickly recur. In many cases, months may pass before a more serious cause like TCC is suspected. This delay can give the tumor time to grow or spread, which significantly affects treatment options and outcomes.

Pet owners play a crucial role in preventing misdiagnosis by tracking patterns and advocating for further testing if symptoms persist beyond one or two antibiotic courses. Early ultrasound imaging and cytology can help rule out cancer much sooner.

Diagnostic Tests Used to Identify Bladder Cancer in Dogs

When bladder cancer is suspected, a series of diagnostic procedures are used to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate the extent of the disease. These may include:

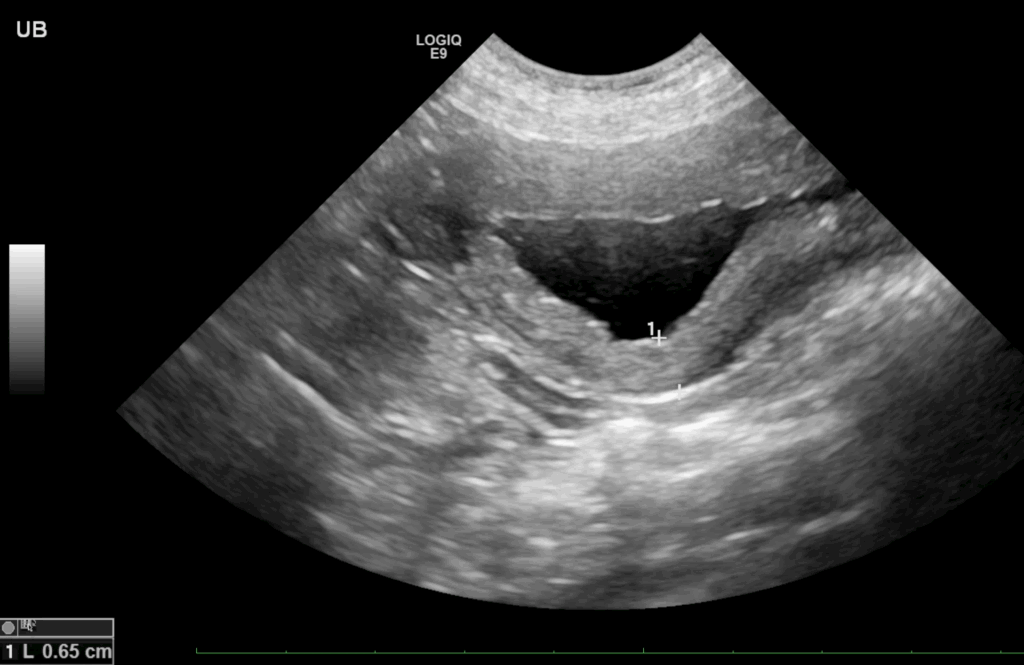

- Abdominal ultrasound to visualize tumors in the bladder wall

- Urinalysis and urine sediment exam to look for cancerous cells or blood

- Urine culture to rule out infections

- Cystoscopy, where a tiny camera is inserted into the urethra to visualize the inside of the bladder

- Biopsy, which remains the gold standard for diagnosis

One advanced test includes a BRAF gene mutation test, which detects DNA markers of TCC in urine samples. This non-invasive test has greatly improved early diagnosis rates, especially in high-risk breeds.

Proper diagnosis not only confirms cancer but helps determine whether surgery, chemotherapy, or NSAIDs might be appropriate. Without precise diagnosis, treatment can become either ineffective or unnecessarily aggressive.

Comparing Canine and Feline Bladder Cancer Presentations

While bladder cancer occurs in both cats and dogs, the clinical presentation and progression often differ. In cats, symptoms tend to be even more subtle, with a lower rate of diagnosis during early stages. Dogs, on the other hand, are more likely to show visible hematuria and pain, prompting earlier veterinary visits.

However, feline bladder cancer (especially transitional cell carcinoma) is often underdiagnosed due to its rarity and the tendency to attribute urinary signs to chronic cystitis or stress-related behaviors. Bladder cancer in cats – as a comparison of diagnostics and symptoms.

Both species benefit from proactive imaging and early cytology. Pet parents and clinicians alike should recognize that lingering urinary symptoms warrant deeper investigation—regardless of species.

How Tumor Location Affects Symptoms and Outcomes

The location of the tumor within the bladder or urinary tract has a significant influence on both the symptoms the dog exhibits and the treatment options available. Tumors near the trigone region—where the bladder connects to the urethra and ureters—are particularly problematic. This area is difficult to operate on due to its anatomical importance and proximity to key urinary structures.

When tumors are located in the neck of the bladder or extend into the urethra, symptoms like straining, obstruction, and urinary retention become more severe. These cases often present late and are less amenable to surgical removal.

Conversely, tumors located on the dorsal bladder wall may be more accessible and less symptomatic early on, making early intervention more feasible.

Veterinarians must assess tumor location via imaging before deciding on treatments such as surgery, NSAID use, or radiation. This anatomic precision directly affects prognosis and quality-of-life expectations.

What Role Does the Prostate Play in Male Dogs With Bladder Cancer?

In male dogs, bladder cancer may extend into the prostate gland, particularly when the tumor originates near the bladder neck or trigone. This proximity allows malignant cells to invade prostatic tissue, leading to prostatitis-like symptoms that further complicate diagnosis.

Affected dogs may present with:

- Straining to urinate or defecate

- Blood in the urine or semen

- Swelling in the perineal area

- Reduced fertility in intact males

In such cases, prostate involvement not only intensifies the clinical picture but also complicates treatment. Some dogs require combined therapy targeting both the bladder and prostate, especially when hormonal influences or androgen-responsive tissues are involved.

Interestingly, the interplay between hormone-driven tissue and cancer recurrence is being studied in other contexts as well, such as in biochemical relapse of prostate cancer in humans, where PSA levels rise despite apparent remission. Biochemical relapse prostate cancer – as a parallel to hormone-dependent relapses.

Treatment Options for Bladder Cancer in Dogs

The treatment plan for bladder cancer in dogs depends on tumor size, location, and whether metastasis has occurred. Common strategies include:

- NSAIDs, especially piroxicam, which can reduce tumor size and inflammation

- Chemotherapy, often with mitoxantrone or vinblastine

- Targeted therapies, including newer agents under trial for veterinary oncology

- Surgery, which is limited to non-trigonal tumors and generally uncommon

- Radiation therapy, offered in select referral hospitals with advanced equipment

NSAIDs are often used even in late stages for palliative care, as they have both anti-inflammatory and mild anti-tumor effects. Multimodal approaches combining NSAIDs with chemotherapy have shown improved outcomes in many cases.

For inoperable tumors, maintaining comfort and quality of life becomes the core focus, often involving pain management, anti-spasmodics, and dietary modifications.

Understanding the Prognosis and Life Expectancy

Prognosis varies significantly depending on when the cancer is diagnosed and how the dog responds to treatment. Without intervention, the average survival time may be a few weeks to 2–3 months. With treatment, many dogs live for 6 to 12 months, and some even longer.

Key factors affecting prognosis include:

- Tumor location (trigonal tumors have worse outcomes)

- Metastatic spread

- Ability to tolerate NSAIDs or chemotherapy

- Age and general health

Some dogs achieve partial remission and maintain a good quality of life for extended periods. Others experience rapid progression, especially if diagnosis is delayed. Quality of life assessments help guide when to shift from curative to palliative care.

Nutritional Support and Home Care for Affected Dogs

Dogs undergoing treatment for bladder cancer benefit from nutritional support, hydration, and a stable home environment. Soft bedding, frequent bathroom breaks, and easy access to clean water and food can all contribute to comfort.

Some veterinarians recommend prescription urinary diets that support bladder health and reduce inflammation. Supplements like omega-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, or anti-inflammatory herbs may also be incorporated under supervision.

Additionally, it’s essential for pet owners to maintain a urinary log, noting the dog’s behavior, frequency, and any visible blood in the urine. This can help the veterinary team adjust treatment or recognize signs of progression.

Environmental and Lifestyle Factors That May Increase Risk

While genetics play a role in bladder cancer predisposition, environmental exposures are strongly implicated in many cases. Studies have found correlations between bladder cancer and:

- Exposure to herbicides (especially those containing phenoxyacetic acids)

- Living near industrial areas

- Prolonged contact with lawn chemicals

- Secondhand smoke

Dogs that spend a lot of time outdoors, especially on treated grass or near polluted water, may absorb toxins through their skin or by grooming. Long-term exposure can lead to DNA mutations in bladder epithelial cells, increasing the chance of malignancy.

These risks are comparable to how environmental carcinogens affect other internal systems in both animals and humans, such as in bile duct cancers, where chronic toxin exposure and inflammation are known contributors. Bile duct cancer icd 10 – in the context of similar risk factors.

Monitoring and Follow-Up: What Happens After Diagnosis?

Once a dog is diagnosed and begins treatment, routine monitoring becomes critical. Follow-ups are usually scheduled every 4 to 6 weeks, and include:

- Ultrasounds to track tumor size and growth

- Urine tests for signs of blood, infection, or recurrence

- Blood work to check organ function during NSAID or chemotherapy treatment

- Pain and symptom assessments to guide palliative adjustments

Monitoring isn’t just about measuring tumor size—it’s about maintaining the best quality of life. Owners are encouraged to keep records of any changes and communicate regularly with their veterinary oncologist. Adjustments to medication, diet, or supportive care can make a meaningful difference in the dog’s comfort and longevity.

Bladder Cancer Symptoms vs. Other Conditions

To help differentiate bladder cancer symptoms from more common urinary issues like infections or stones, here is a side-by-side overview:

| Symptom | Bladder Cancer | Urinary Tract Infection | Bladder Stones |

| Blood in urine | Common and persistent | Common but resolves with antibiotics | Intermittent, especially after activity |

| Straining to urinate | Severe and progressive | Mild to moderate | Severe, especially if obstructed |

| Urine dribbling | Frequent and worsening | Occasional | May occur after urination |

| Fever | Rare | Often present | Rare |

| Appetite loss | Common in later stages | Uncommon | Rare |

| Response to antibiotics | Poor | Good response within days | No response |

This comparison is helpful for both clinicians and pet owners to understand when to dig deeper beyond initial assumptions of infection.

Key Takeaways for Dog Owners Facing a Bladder Cancer Diagnosis

Facing a bladder cancer diagnosis in a beloved dog is never easy. Yet, with early recognition and informed action, there is hope for comfort, management, and quality time.

Key reminders:

- Don’t ignore urinary symptoms that recur or resist antibiotics

- Certain breeds like Scottish Terriers face higher risk

- Early testing and imaging are critical for better outcomes

- Treatment can extend life and reduce suffering, even if cure is not possible

Ultimately, bladder cancer care is about making compassionate, informed decisions based on your dog’s unique needs and the best available veterinary support.

FAQ

What are the earliest symptoms of bladder cancer in dogs?

The earliest signs are often subtle and may include blood in the urine, straining to urinate, and frequent urination with little output. These symptoms can mimic urinary tract infections, which is why they’re often overlooked or misdiagnosed in the initial stages.

Can bladder cancer be cured in dogs?

While a complete cure is rare, especially in cases diagnosed late or involving the trigone region, many dogs can achieve partial remission or experience a slowed progression of the disease with proper treatment. Long-term management is often the goal, focusing on comfort and quality of life.

How is bladder cancer diagnosed in dogs?

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of abdominal ultrasound, urinalysis, urine cytology, and sometimes cystoscopy or biopsy. A genetic test for the BRAF gene mutation may also be used to confirm transitional cell carcinoma using a urine sample.

Does bladder cancer spread to other organs in dogs?

Yes, it can. The most common metastatic sites include local lymph nodes, lungs, and other parts of the urinary tract. However, many dogs experience severe local complications before widespread metastasis becomes apparent.

How long can a dog live with bladder cancer?

Survival time varies widely. Without treatment, dogs may live only a few weeks to a couple of months. With NSAIDs and/or chemotherapy, many live six months to a year, and occasionally longer with strong response to treatment and minimal metastasis.

Is bladder cancer painful for dogs?

It can become painful, particularly when the tumor obstructs the urinary flow or causes bladder wall irritation. Pain management, including anti-inflammatory medications, is an essential component of supportive care for affected dogs.

Are some dogs more likely to get bladder cancer than others?

Yes. Breeds such as Scottish Terriers, Beagles, and West Highland White Terriers are at higher risk. Age is also a factor, with most cases occurring in dogs over 8 years old. Female dogs are slightly more affected than males.

Can diet prevent bladder cancer in dogs?

There is no proven dietary prevention, but keeping your dog well-hydrated and avoiding exposure to known carcinogens like lawn chemicals may help reduce risk. Special urinary health diets may support bladder wellness but won’t prevent cancer.

How do I know if treatment is working?

Veterinarians monitor progress using repeat imaging (such as ultrasound) and urine analysis. If symptoms improve, tumors shrink, and quality of life remains good, treatment is considered effective—even if not curative.

Can I treat my dog’s bladder cancer at home?

While at-home care supports comfort—through hydration, pain relief, and reduced stress—primary treatments like NSAIDs and chemotherapy require veterinary oversight. Never attempt to treat bladder cancer without professional guidance.

Is bladder cancer in dogs contagious to other pets?

No. Bladder cancer is not contagious and cannot be transmitted to other pets or humans. It is caused by genetic mutations and environmental factors, not infection or contact.

What happens if the cancer blocks my dog’s urethra?

Urethral obstruction is a medical emergency. If your dog is unable to urinate, you must seek immediate veterinary care. Options may include catheterization, emergency surgery, or stenting to restore urine flow.

What’s the difference between bladder infection and bladder cancer symptoms?

Both may cause blood in the urine, straining, and frequent urination. However, infections usually respond quickly to antibiotics. If symptoms persist or worsen, bladder cancer should be ruled out with advanced diagnostics.

How often should my dog be checked after a diagnosis?

Most veterinarians recommend follow-up every 4–6 weeks to assess tumor size, check lab results, and adjust medications. Close monitoring helps ensure the best quality of life and catches progression early.

When should I consider euthanasia for a dog with bladder cancer?

This decision is deeply personal. Signs it may be time include severe pain, loss of appetite, incontinence, or inability to urinate despite treatment. Open dialogue with your vet can guide this compassionate choice.