Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Eyelid: A Complete Guide for Early Detection and Treatment

- What Is Eyelid Basal Cell Carcinoma and Why Is It So Common?

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Eyelid Skin Cancer

- Causes and Risk Factors Behind Eyelid BCC

- How Eyelid BCC Is Diagnosed and Why Biopsy Is Essential

- Understanding the Types of Eyelid Basal Cell Carcinoma

- Mohs Micrographic Surgery: The Gold Standard Treatment

- Reconstruction After Eyelid Tumor Removal

- Radiation Therapy and When It’s Used

- Eyelid BCC in High-Risk Populations: Immunosuppressed and Elderly

- Differentiating BCC From Other Eyelid Lesions

- Long-Term Monitoring and Recurrence Risk

- Cosmetic and Psychological Considerations in Eyelid Cancer Recovery

- How to Protect Your Eyelids From UV Damage

- The Role of Dermoscopy and Non-Invasive Imaging

- Key Facts About Eyelid BCC

- Empowering Patients With Knowledge and Preventive Action

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What Is Eyelid Basal Cell Carcinoma and Why Is It So Common?

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most prevalent form of skin cancer, and when it develops on the eyelid, it becomes a unique clinical challenge. This type of cancer originates from basal cells located in the epidermis, the skin’s outermost layer. On the eyelid, BCC is especially concerning due to the delicate anatomy and proximity to the eye itself.

The eyelids are exposed to significant ultraviolet (UV) radiation, especially the lower lid, which explains why over 90% of eyelid BCC cases occur there. While this cancer type rarely metastasizes, it can be locally invasive, causing significant cosmetic and functional damage if not treated promptly.

Patients may mistake early BCC for benign conditions like styes or chalazia, leading to delays in diagnosis. Understanding the nature of eyelid BCC and differentiating it from other lesions is crucial for preserving both ocular health and facial integrity.

Recognizing the Warning Signs of Eyelid Skin Cancer

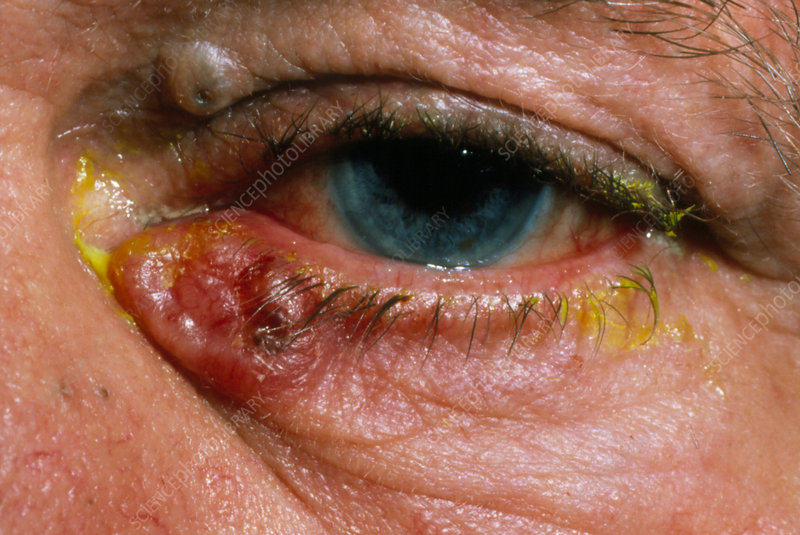

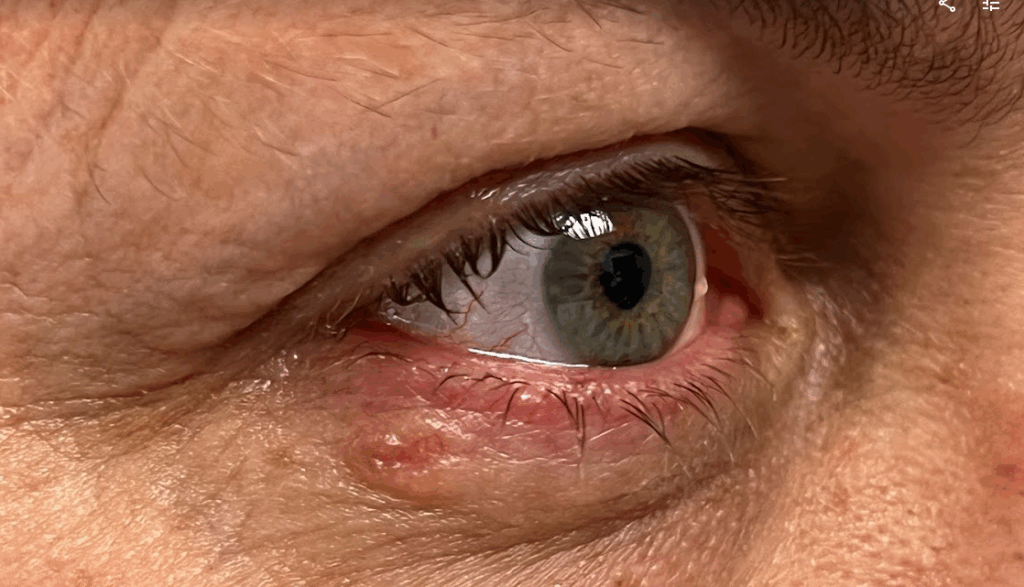

The appearance of basal cell carcinoma on the eyelid can vary, but several hallmark signs can raise suspicion. Patients often notice a pearly or waxy bump, sometimes with visible blood vessels (telangiectasia), or a sore that doesn’t heal. Over time, the lesion may ulcerate or form a crust. In some cases, BCC appears as a flat, scar-like area that gradually enlarges.

Unlike inflamed lesions, these nodules are usually painless and slow-growing, which unfortunately contributes to delayed medical attention. Other signs include loss of eyelashes, bleeding, or subtle changes in lid contour. Any persistent skin change in the eyelid area should be evaluated by a dermatologist or oculoplastic specialist, especially in fair-skinned individuals with high UV exposure.

In postmenopausal women or immunocompromised patients, slow-growing masses—regardless of discomfort—should prompt early investigation, as similar delays often occur in conditions like bartholin cyst cancer.

Causes and Risk Factors Behind Eyelid BCC

Basal cell carcinoma is primarily driven by cumulative UV exposure, particularly in individuals with light skin, blue or green eyes, and a history of sunburns or tanning bed use. The eyelid’s thin skin and frequent sun exposure—especially on the lower lid—make it a prime site for cellular damage from UVB and UVA rays.

Other risk factors include older age, male gender, previous history of skin cancer, and immunosuppression. Genetic conditions like basal cell nevus syndrome (Gorlin syndrome) may predispose individuals to develop multiple BCCs across the body, including the eyelids.

Unlike melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma, BCC is less likely to metastasize. However, the periocular region’s compact anatomy increases the risk of local invasion into the eye socket, tear ducts, or nasal sidewall—leading to significant disfigurement or vision compromise.

How Eyelid BCC Is Diagnosed and Why Biopsy Is Essential

A clinical suspicion of eyelid BCC must always be confirmed through biopsy, the gold standard for diagnosis. A shave, punch, or incisional biopsy is typically performed by a dermatologist, oculoplastic surgeon, or ophthalmologist with training in periocular oncology. The tissue sample is then examined microscopically to assess cellular characteristics and confirm the diagnosis.

BCCs have distinct histological features, including nests of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading, and stromal retraction. These microscopic clues help differentiate BCC from other tumors like sebaceous carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, which may require different treatments.

In some cases, imaging studies like orbital CT or MRI may be needed if there’s concern about deeper invasion. Just as deeper tumors may remain asymptomatic in early stages—as with axillary lump breast cancer—eyelid BCC can silently extend beneath the surface.

Understanding the Types of Eyelid Basal Cell Carcinoma

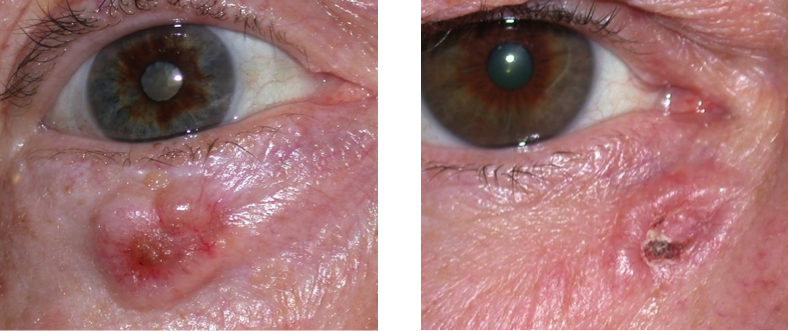

Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid presents in several histological subtypes, each with its own pattern of growth and clinical behavior. The most common form is the nodular subtype, which appears as a raised, pearly bump, often with visible surface blood vessels. It is generally slow-growing and well-defined, making it easier to detect and treat early.

The infiltrative or morpheaform subtype is more aggressive. It tends to grow beneath the skin’s surface with ill-defined borders, making complete surgical removal more difficult. This variant may mimic scar tissue and is often diagnosed late due to its subtle appearance.

Other types include superficial BCC, which appears as red, scaly patches, and pigmented BCC, which contains melanin and may be confused with melanoma. Knowing the subtype is critical because it influences surgical margins, recurrence risk, and follow-up care plans.

Mohs Micrographic Surgery: The Gold Standard Treatment

For most cases of eyelid BCC, Mohs micrographic surgery is the preferred treatment. This highly specialized technique allows for precise tumor removal with minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissue—an essential consideration in the aesthetically and functionally sensitive eye region.

During the procedure, thin layers of skin are removed and examined under a microscope in real-time. This process continues until no cancer cells are detected in the margins. The result is a high cure rate and optimal tissue preservation, reducing the need for extensive reconstructive surgery.

Because of the eyelid’s anatomical complexity, Mohs surgery is often performed in coordination with an oculoplastic surgeon, who immediately reconstructs the affected area. This interdisciplinary approach minimizes visual impairment and improves cosmetic outcomes.

Reconstruction After Eyelid Tumor Removal

Eyelid reconstruction following BCC excision is both an art and a science. It involves restoring eyelid function—like blinking and protecting the eye—while also maintaining symmetry and appearance. The choice of technique depends on tumor size, location, and extent of tissue loss.

Small defects may be closed with primary closure, while moderate-sized ones may require local flaps—rotated or transposed tissue from adjacent skin. For larger defects, skin grafts or composite grafts (including cartilage for structural support) might be necessary.

Recovery typically involves temporary swelling, bruising, and a follow-up plan to monitor healing. Patients are educated on signs of recurrence and complications, similar to protocols seen in other surgical oncology contexts, such as post-treatment surveillance for back ache bowel cancer where local symptoms may indicate residual disease.

Radiation Therapy and When It’s Used

While surgery remains the first-line treatment, radiation therapy plays a role in specific situations—particularly for patients who are not surgical candidates due to age, medical comorbidities, or tumor location. Radiation is also considered for recurrent tumors, incompletely excised tumors, or aggressive subtypes where surgical margins are unclear.

External beam radiation is typically delivered over several sessions. It works by targeting rapidly dividing cancer cells while sparing as much surrounding tissue as possible. Despite its effectiveness, radiation may cause skin irritation, loss of eyelashes, dry eye, or chronic inflammation in the treated area.

Long-term monitoring is necessary since radiation can increase the risk of local tissue changes or, rarely, secondary malignancies. The decision to use radiation requires collaboration between dermatologic oncologists, radiation specialists, and oculoplastic surgeons to ensure balanced care.

Eyelid BCC in High-Risk Populations: Immunosuppressed and Elderly

Certain populations are at higher risk for developing aggressive or recurrent basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Immunosuppressed patients, including those who have undergone organ transplantation or are on long-term immunosuppressive therapy, are more susceptible to skin cancers that behave more aggressively and grow more rapidly.

In the elderly, the risk increases both due to cumulative UV exposure and delayed immune surveillance. Older adults may also have thinner skin and a higher likelihood of comorbidities, which can limit treatment options. Delayed detection is common due to reduced access to care, misattribution of symptoms to aging, or less concern over slow-growing lesions.

These factors make early dermatologic screening and education essential in vulnerable populations. Just as with Bartholin gland cancer, where age and immune changes influence disease risk and progression, a proactive approach is critical to improving outcomes in periocular BCC.

Differentiating BCC From Other Eyelid Lesions

Eyelid BCC can mimic various benign and malignant conditions, making differential diagnosis essential. Common misdiagnoses include chalazion, blepharitis, sebaceous gland carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and actinic keratosis. Each of these has overlapping features, but there are subtle differences that help clinicians narrow the possibilities.

For example, a chalazion tends to be painless, transient, and resolves with warm compresses or steroid injection. In contrast, BCCs persist and slowly enlarge. Sebaceous carcinomas often involve loss of eyelashes, yellowish hue, and tarsal plate thickening, which are less typical in BCC.

Pathological confirmation through biopsy is the definitive method for distinguishing BCC from its mimickers. Multidisciplinary review of clinical, histologic, and imaging findings ensures that the right diagnosis is made the first time—preventing under- or overtreatment.

Long-Term Monitoring and Recurrence Risk

Although basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid is highly treatable, recurrence is not uncommon, especially in cases with positive margins, aggressive histologic subtypes, or incomplete treatment. Surveillance is essential to detect local recurrence, which may occur months or even years after initial therapy.

Most recurrences develop within five years, but some may take longer, particularly in cases of morpheaform BCC or in immunosuppressed patients. Regular follow-up with dermatologists and ophthalmologists is recommended, typically involving annual skin checks, eyelid photography, and, if needed, periodic imaging.

Patients should be educated to report any new growth, bleeding, or changes in the surgical area. Just as with axillary lump breast cancer or colorectal recurrences, vigilance over time is critical to ensuring long-term disease control and quality of life. Axillary lump breast cancer as an example of cancer with a high risk of local recurrence.

Cosmetic and Psychological Considerations in Eyelid Cancer Recovery

Even after successful treatment, patients with eyelid BCC often face emotional and cosmetic challenges. The face—and especially the eyes—are central to identity and interpersonal communication. Surgical scars, asymmetry, or loss of eyelashes may impact confidence and cause anxiety or depression.

Patients may also fear recurrence or feel disfigured despite oncologic success. Access to reconstructive specialists, psychological counseling, and support groups can help restore well-being. Interventions such as medical tattooing, eyelash transplants, or cosmetic camouflage may also assist in restoring appearance.

Holistic care must address not only tumor removal but also restoration of a person’s self-image, emotional health, and sense of control—elements as critical in dermatologic oncology as they are in any cancer care pathway.

How to Protect Your Eyelids From UV Damage

Prevention plays a crucial role in reducing the risk of eyelid BCC. Since ultraviolet radiation is the primary cause of skin cancer in this area, the most effective protective measure is UV avoidance and shielding. However, because the eyelids are thin and often missed during sunscreen application, they remain particularly vulnerable.

Wearing wide-brimmed hats, UV-blocking sunglasses, and broad-spectrum sunscreen around the eye area is essential. For individuals with sensitive skin or those prone to ocular irritation, mineral-based sunscreens with zinc oxide or titanium dioxide are often better tolerated.

Additionally, avoiding tanning beds and minimizing peak sun exposure hours significantly reduces cumulative UV damage. This strategy is especially important in individuals with prior history of skin cancer or other high-risk features. Long-term protection requires daily habits and public awareness, especially since the eyelids are among the most commonly overlooked regions in sun safety routines.

The Role of Dermoscopy and Non-Invasive Imaging

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive diagnostic tool that enhances the visualization of skin structures and vascular patterns not visible to the naked eye. In the context of eyelid lesions, it allows for better differentiation between benign and malignant features, such as arborizing vessels, ulceration, or pigmentary changes typical of basal cell carcinoma.

Advanced technologies such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) are also being used in research and specialty settings. These methods provide real-time imaging of skin layers and help evaluate tumor margins without biopsy—offering a promising alternative for sensitive sites like the eyelid.

Such tools can improve diagnostic precision and reduce unnecessary procedures. While not yet standard in every clinical setting, they represent the future of non-invasive oncology diagnostics, especially for cosmetically critical zones like the face and periocular region.

Key Facts About Eyelid BCC

| Feature | Description |

| Most Common Location | Lower eyelid |

| Typical Appearance | Pearly, waxy nodule; may ulcerate |

| Primary Risk Factor | Chronic UV exposure |

| Most Affected Population | Fair-skinned individuals >60 years old |

| Gold Standard Treatment | Mohs micrographic surgery |

| Aggressive Subtypes | Morpheaform, infiltrative |

| Recurrence Risk | Higher in incompletely excised or aggressive tumors |

| Preventive Measures | Sunscreen, sunglasses, regular skin checks |

| Surveillance Needs | Annual follow-up, especially in high-risk or post-treatment patients |

| Psychosocial Support | Important for body image and emotional recovery after surgery |

This overview helps both clinicians and patients understand the multifaceted nature of eyelid BCC—from visual recognition to treatment and follow-up. It also highlights why early intervention matters for both medical and aesthetic outcomes.

Empowering Patients With Knowledge and Preventive Action

Empowering individuals with education and proactive health strategies is the final step in battling eyelid BCC. Early recognition, routine dermatologic visits, and awareness of sun protection are essential. Equally important is encouraging patients to speak up when changes occur, rather than dismissing subtle growths or discolorations near the eye.

Just as conditions like back ache from bowel cancer may go unnoticed due to vague or unrelated symptoms, eyelid BCC often escapes early detection because it mimics benign issues. Back ache bowel cancer is an example of underestimated signs of serious conditions.

Clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion and use biopsy liberally for persistent lesions. Meanwhile, patients can take ownership through lifestyle changes, regular screening, and understanding what “normal” looks and feels like on their own skin. In the battle against skin cancer, knowledge remains the most accessible and powerful weapon.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid?

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the eyelid is a slow-growing, non-melanoma skin cancer that originates in the basal cells of the epidermis. While not typically life-threatening, it can cause significant tissue destruction and cosmetic disfigurement if not treated early.

How do I know if an eyelid bump is cancerous?

Unlike a stye or chalazion, cancerous eyelid lesions tend to be firm, painless, and persistent. They may ulcerate, bleed, or cause loss of eyelashes. Any lesion that does not heal within a few weeks should be evaluated by a specialist.

Is eyelid BCC dangerous?

Though rarely metastatic, it can invade nearby tissues, including the eye, muscles, and bone. If left untreated, it may cause vision loss, facial asymmetry, or require disfiguring surgery.

What causes basal cell carcinoma on the eyelid?

The main cause is cumulative exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun or tanning beds. Other contributing factors include fair skin, aging, genetic predisposition, and immune suppression.

What’s the most common location for eyelid BCC?

Over 90% of eyelid BCCs occur on the lower eyelid, due to its higher sun exposure and thinner skin. The inner canthus (corner near the nose) is also a frequent site.

How is eyelid BCC diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves a clinical exam followed by a biopsy to confirm the cancer and determine its subtype. Imaging may be used if deeper invasion is suspected.

What is the best treatment for eyelid basal cell carcinoma?

Mohs micrographic surgery is considered the gold standard because it allows complete tumor removal with minimal damage to surrounding tissue, especially valuable in the eye area.

Can BCC come back after treatment?

Yes, recurrence is possible—especially with aggressive subtypes or incomplete removal. Regular follow-up is crucial to catch any returning cancer early.

Does basal cell carcinoma spread to other organs?

It very rarely metastasizes. However, it can grow deeply into surrounding tissues, which can lead to serious local complications if not managed properly.

Are radiation and chemotherapy used for eyelid BCC?

Radiation is considered when surgery is not an option or after incomplete removal. Chemotherapy is rarely used unless the cancer is advanced or recurrent.

What’s the difference between BCC and other eyelid cancers?

BCC is the most common eyelid malignancy and typically less aggressive. Others, like sebaceous gland carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma, have different histology, higher metastatic risk, and require different treatment strategies.

Is eyelid BCC painful?

Usually not. Its painless nature often leads to delays in seeking treatment, which can worsen outcomes.

How can I prevent eyelid BCC?

Use sunscreen around the eyes, wear UV-protective sunglasses, and avoid prolonged sun exposure. Routine skin checks are essential, especially for high-risk individuals.

What should I do if I’ve had BCC before?

People who’ve had BCC are more likely to develop another. Lifelong dermatologic follow-up is important, as well as practicing rigorous sun protection habits.

Are there other cancers that behave similarly?

Yes. Like Bartholin gland cancer or axillary lump breast cancer, BCC may appear innocuous but progress locally in ways that impact critical structures. Bartholin cyst cancer and axillary lump breast cancer as analogs of locally invasive tumors.