Bartholin Cyst Cancer: Rare but Critical to Recognize

- Understanding the Bartholin Glands and Common Cyst Formation

- When a Bartholin Cyst May Be More Than a Cyst

- Types of Cancer Arising from the Bartholin Gland

- Clinical Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

- Diagnostic Approach: From Clinical Exam to Biopsy

- Staging Bartholin Gland Cancer: Understanding Disease Spread

- Surgical Treatment Options and Reconstruction Techniques

- Adjuvant Therapy: Radiation and Chemotherapy Considerations

- Prognosis and Long-Term Survival Outcomes

- Psychological Impact and Sexual Health After Diagnosis

- Recurrence and Risk of Metastasis

- Key Features of Bartholin Cyst Cancer

- Importance of Early Recognition in Primary Care Settings

- Differences Between Bartholin Cysts and Cancer: What to Watch For

- Educational Campaigns and Public Awareness

- Survivorship, Monitoring, and Living Beyond Cancer

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Understanding the Bartholin Glands and Common Cyst Formation

The Bartholin glands are two small, pea-sized glands located on each side of the vaginal opening. Their primary function is to secrete mucus that lubricates the vaginal vestibule, particularly during sexual arousal. These glands connect to the surface via small ducts, which can become blocked due to inflammation, infection, or trauma. When this occurs, fluid accumulates, forming what is known as a Bartholin cyst.

Most Bartholin cysts are benign and asymptomatic, often discovered incidentally during routine pelvic examinations. However, they can occasionally become infected, forming a painful abscess that requires drainage. The vast majority of these cysts are not dangerous and respond well to conservative treatment. Nevertheless, in rare cases—particularly in postmenopausal women—a persistent or recurrent Bartholin cyst may harbor malignancy, warranting closer investigation.

When a Bartholin Cyst May Be More Than a Cyst

While benign Bartholin cysts are common, Bartholin gland carcinoma is extremely rare, accounting for less than 1% of all vulvar cancers. It most frequently affects women over the age of 50 and is often misdiagnosed or overlooked due to its similarity in presentation to benign cysts. Malignancy should be suspected when a cyst is solid, unilateral, painless but persistent, and located deep within the vulvar tissue.

In many cases, women delay seeking care due to minimal discomfort or embarrassment, allowing the tumor to grow undetected. Additionally, healthcare providers may initially treat the lesion as a simple abscess, missing the underlying neoplastic process. This makes histological examination of persistent Bartholin masses essential, particularly in women who are postmenopausal or have a history of gynecologic cancers.

Clinical vigilance is key. Any Bartholin mass that does not resolve with standard treatment, recurs multiple times, or presents with atypical features should be evaluated for malignancy through biopsy and imaging.

Types of Cancer Arising from the Bartholin Gland

Bartholin gland carcinoma is not a single entity but encompasses several histological subtypes, each with its own behavior, prognosis, and treatment strategy. The most common type is adenocarcinoma, which originates from the mucus-secreting epithelial cells of the gland. This is followed by squamous cell carcinoma, arising from the skin lining the duct, and the more aggressive adenoid cystic carcinoma, known for perineural invasion and high recurrence rates.

Other rare types include transitional cell carcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma, each carrying varying prognostic significance. Accurate histopathological classification is crucial, as it informs surgical planning and the need for adjunctive therapies such as radiation or chemotherapy.

Because these subtypes often resemble benign lesions on physical exam, a biopsy remains the definitive method of diagnosis. Moreover, advanced imaging techniques may help delineate the extent of local invasion, lymph node involvement, and potential metastasis.

Clinical Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

One of the challenges in diagnosing Bartholin gland cancer is its subtle presentation, especially in early stages. Most patients report a lump in the vulvar region that feels firm or irregular. Unlike infected cysts, cancerous lesions may be painless, non-tender, and slowly enlarging. Discomfort during intercourse (dyspareunia), difficulty walking, or a feeling of pressure in the genital area may develop as the tumor expands.

In more advanced stages, symptoms may include bloody or foul-smelling discharge, swelling of nearby lymph nodes, or pelvic and lower back pain, depending on the degree of local spread. These signs can overlap with other gynecologic or gastrointestinal conditions, leading to misdiagnosis or delayed care.

Diagnostic Approach: From Clinical Exam to Biopsy

Diagnosing Bartholin gland cancer begins with a thorough pelvic examination, during which the clinician evaluates the size, consistency, and mobility of any vulvar or glandular mass. While benign cysts are typically soft and fluctuant, malignant lesions often feel firm, irregular, and deeply embedded in the vulvar tissue. When suspicion arises, further evaluation is essential.

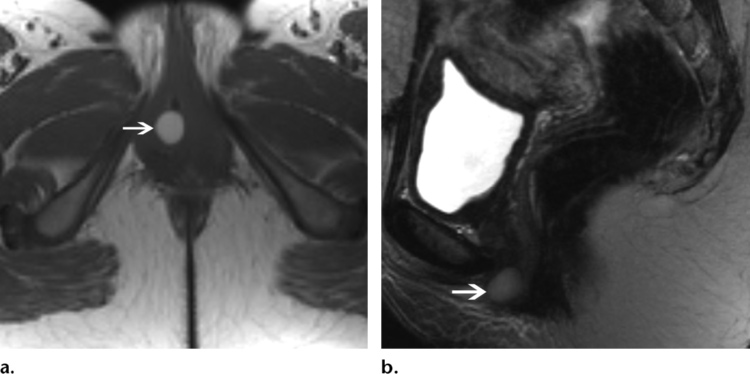

Imaging studies are frequently employed to assess the extent of disease. Pelvic MRI offers detailed visualization of soft tissue involvement, while ultrasound may help distinguish solid from cystic components. In cases where lymph node spread is a concern, CT or PET scans can assist in staging.

The definitive diagnosis is made through biopsy, usually via excisional or core needle technique. This not only confirms malignancy but also identifies the cancer subtype, which is critical for guiding treatment. In women over 40, especially those who are postmenopausal, any Bartholin gland mass should be biopsied to exclude carcinoma, regardless of clinical suspicion.

Staging Bartholin Gland Cancer: Understanding Disease Spread

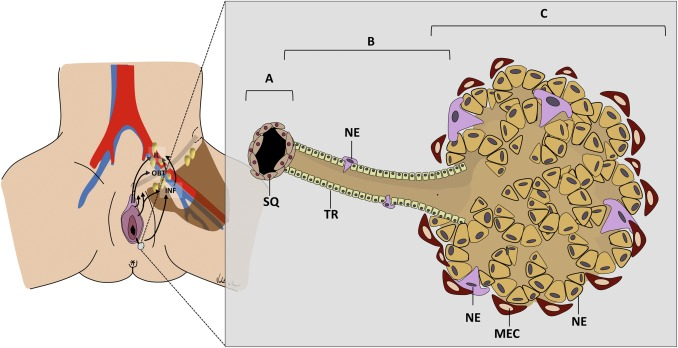

Like other vulvar cancers, Bartholin gland malignancies are staged using the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) system. Staging considers tumor size, depth of invasion, and regional or distant metastasis, including involvement of inguinal and pelvic lymph nodes. This staging determines prognosis and informs the aggressiveness of the treatment approach.

Stage I tumors are confined to the Bartholin gland and surrounding vulvar tissue. Stage II and III involve adjacent structures such as the vagina, urethra, or anus, or show regional lymph node spread. Stage IV indicates distant metastases or invasion of critical structures like the pelvic bone or rectum.

Accurate staging requires a combination of physical examination, imaging, and often sentinel lymph node biopsy or full inguinal-femoral node dissection. Because of the gland’s anatomic proximity to multiple pelvic structures, even small tumors may infiltrate deeper than they appear on inspection, making imaging indispensable.

Surgical Treatment Options and Reconstruction Techniques

Surgery remains the cornerstone of treatment for most cases of Bartholin gland cancer. The extent of surgery depends on tumor size, location, and invasion of adjacent structures. Wide local excision or simple vulvectomy may suffice for early-stage disease. However, larger or infiltrative tumors often require radical vulvectomy, potentially involving the vagina, urethra, or anus.

When lymph nodes are involved or at high risk for harboring cancer, inguinal and femoral lymphadenectomy is often indicated. This carries a risk of complications such as lymphedema, infection, and wound healing issues, but can be life-saving.

In patients undergoing extensive tissue removal, reconstructive surgery may be required to restore vulvar anatomy and function. Flap reconstruction, using local or regional tissue, is performed by plastic or gynecologic oncologic surgeons to reduce physical discomfort and improve cosmetic outcomes. Postoperative care focuses on infection prevention, wound healing, and pelvic floor rehabilitation.

Adjuvant Therapy: Radiation and Chemotherapy Considerations

Depending on tumor stage, margins, and nodal involvement, adjuvant therapy may be necessary after surgery. Radiation therapy is often used when there is concern about residual microscopic disease, close or positive surgical margins, or extensive lymph node involvement. It can be delivered externally or via brachytherapy to the vulvar and pelvic region.

Chemotherapy, although less commonly used for localized disease, may be indicated in advanced stages or in combination with radiation for radiosensitization. Agents like cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, or taxanes are commonly used, depending on the histological subtype and patient’s performance status.

Patients must be closely monitored for treatment-related side effects such as skin irritation, vaginal stenosis, fatigue, and hematologic toxicity. Supportive care, including nutritional counseling, hydration, and psychosocial support, plays a key role in maintaining quality of life during treatment.

Prognosis and Long-Term Survival Outcomes

Bartholin gland cancer has a variable prognosis depending on factors such as stage at diagnosis, histological subtype, lymph node involvement, and adequacy of surgical margins. In general, early-stage tumors that are completely excised with negative margins carry a favorable outlook, with 5-year survival rates approaching 80–90%. However, once the cancer spreads to lymph nodes or adjacent organs, the prognosis worsens significantly.

Adenoid cystic carcinoma, while slow-growing, is notorious for perineural invasion and local recurrence. These cases may have a prolonged clinical course but require vigilant, long-term surveillance. Conversely, poorly differentiated or high-grade carcinomas tend to behave more aggressively and may relapse early despite treatment.

Survivors require regular follow-up visits, including physical examinations, imaging, and attention to symptoms like pelvic pain or vulvar changes. Recurrence may occur years after initial treatment, reinforcing the importance of ongoing surveillance for life, especially in high-risk histologic types.

Psychological Impact and Sexual Health After Diagnosis

Receiving a diagnosis of vulvar or Bartholin gland cancer can be emotionally devastating. Due to the intimate nature of the disease, many patients experience feelings of embarrassment, vulnerability, and anxiety. Surgical treatment may significantly alter vulvar anatomy and body image, potentially affecting sexual function, identity, and intimacy.

Women may face physical barriers to intercourse, such as vaginal narrowing, scarring, and pain, in addition to psychological reluctance. Counseling, open communication with partners, and guidance from a specialized pelvic floor physical therapist can help patients navigate these changes.

Psychosocial support is crucial throughout the care journey. Involvement of a mental health professional, support groups, and sexual health educators can greatly improve quality of life and help patients regain confidence and a sense of normalcy.

Recurrence and Risk of Metastasis

Bartholin gland cancers carry a moderate-to-high risk of recurrence, depending on the cancer subtype and how early it was detected. Most recurrences occur locally in the vulvar region, particularly when initial surgical margins were close or positive. Regional nodal recurrence, especially in the inguinal area, is also common in more advanced stages.

Distant metastasis—though less frequent—can involve the lungs, liver, or bone. Symptoms such as chronic pelvic pain, unrelenting back ache, or new respiratory complaints should prompt immediate evaluation.

Follow-up protocols often include pelvic exams every 3–6 months in the first two years, then annually thereafter. Imaging may be scheduled periodically or symptom-driven. Recurrence does not necessarily equate to poor survival but typically requires more aggressive salvage therapy, including surgery, radiation, or systemic treatment.

Key Features of Bartholin Cyst Cancer

| Clinical Feature | Description |

| Typical Age at Presentation | Most common in women over 50 |

| Initial Symptom | Persistent, firm lump near vaginal opening |

| Common Misdiagnosis | Benign cyst or abscess |

| Histologic Subtypes | Adenocarcinoma, squamous cell, adenoid cystic |

| Diagnostic Tools | Pelvic exam, MRI, biopsy |

| Primary Treatment | Surgical excision or vulvectomy |

| Adjuvant Therapy | Radiation ± chemotherapy, based on margins and nodal spread |

| Prognosis | Good in early stages, guarded in node-positive or recurrent disease |

| Follow-Up Recommendations | Every 3–6 months for 2 years, then annually |

| Psychosexual Impact | Often significant; requires counseling and support |

This summary table helps synthesize the complex clinical course of Bartholin gland cancer into a reference format, supporting both patient education and provider decision-making.

Importance of Early Recognition in Primary Care Settings

Primary care and women’s health providers often serve as the first point of contact when patients present with vulvar symptoms. Recognizing when a seemingly benign Bartholin cyst may be suspicious is crucial. A mass that is unilateral, non-resolving, firm, or located in a postmenopausal patient should never be assumed benign without further workup.

Unfortunately, routine reliance on clinical appearance alone can lead to misdiagnosis or delayed referral. Incorporating a protocol where any persistent Bartholin mass in women over 40 is biopsied may improve early cancer detection rates. Education around this topic should be included in continuing medical education for general practitioners, gynecologists, and nurse practitioners.

Creating a low-threshold for referral to gynecologic oncology can drastically alter prognosis, offering patients a chance at early intervention and curative treatment.

Differences Between Bartholin Cysts and Cancer: What to Watch For

Though Bartholin cysts and Bartholin gland cancer can look similar externally, certain differences can help distinguish them:

- Bartholin cysts are usually soft, mobile, and painless unless infected. They commonly occur in younger women and are fluid-filled.

- Bartholin gland cancers, by contrast, are often firm, fixed, and persist beyond typical infection cycles. They tend to arise in older women and are often associated with solid components on imaging.

Symptoms like blood-stained discharge, lymph node enlargement, or ulceration of the skin overlying the mass are also more typical of malignancy. These distinctions should prompt additional investigation rather than empirical treatment alone. Prostate cancer screening – especially in the context of discussing early detection programs for cancer, the importance of age-based guidelines and surveillance protocols.

Educational Campaigns and Public Awareness

Because of its rarity, Bartholin gland cancer receives very little public attention. This leads to a lack of awareness both among patients and providers. Women often delay seeking evaluation for vulvar symptoms, either due to embarrassment or a false sense of security that the issue is “just a cyst.”

Targeted educational campaigns, especially those focused on postmenopausal women’s health, could improve detection. Visual aids, symptom checklists, and digital platforms can play a role in increasing understanding and prompting earlier clinical visits.

Medical institutions should also improve patient information materials on vulvar health, making it easier for women to differentiate benign from worrisome signs. Integrating this topic into broader cancer education can prevent cases from slipping through the cracks.

Survivorship, Monitoring, and Living Beyond Cancer

Surviving Bartholin gland cancer involves more than physical healing. Women often require long-term monitoring for recurrence, support for sexual and urinary function, and assistance in coping with the emotional aftermath of cancer treatment.

Survivorship care should include structured follow-up visits, as well as access to pelvic floor therapy, pain management, and mental health services. Reconstructive surgery or cosmetic revisions may also be considered to improve confidence and comfort.

Emphasis should be placed on empowerment and quality of life—through community support groups, survivorship planning, and personal care routines. With continued research and individualized care, women affected by this rare disease can lead full, meaningful lives well beyond diagnosis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Is a Bartholin cyst the same as Bartholin gland cancer?

No. A Bartholin cyst is a benign fluid-filled sac caused by blockage of the gland’s duct, whereas Bartholin gland cancer is a rare malignant tumor. While cysts are common and usually harmless, persistent or unusual masses may warrant cancer evaluation.

Who is most at risk for Bartholin gland cancer?

Women over the age of 50, especially those who are postmenopausal, are at higher risk. Recurrent or non-resolving Bartholin masses in this age group should always be investigated more thoroughly with biopsy and imaging.

What symptoms suggest a Bartholin cyst might be cancerous?

Symptoms like a firm or fixed mass, ulceration, persistent growth, or bloody discharge are suspicious. Lack of pain or signs of infection in an enlarging mass is also concerning, particularly in older women.

How is Bartholin gland cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis requires a combination of pelvic examination, imaging (MRI or ultrasound), and histological confirmation through biopsy. A full cancer workup may follow, including staging scans if malignancy is confirmed.

Can Bartholin gland cancer spread to other parts of the body?

Yes. It can spread to nearby structures like the vagina or rectum and to lymph nodes in the groin and pelvis. In advanced stages, it may metastasize to distant organs such as the lungs or liver.

What is the typical treatment for Bartholin gland cancer?

Treatment often involves surgical excision of the tumor and, if necessary, surrounding tissue or lymph nodes. Adjuvant radiation or chemotherapy may follow depending on stage, margins, and lymphatic spread.

Is surgery for Bartholin cancer disfiguring?

The extent of surgery varies, but radical procedures may affect the anatomy and appearance of the vulva. Reconstructive techniques can help restore function and aesthetics, and should be discussed before surgery.

Can a benign Bartholin cyst turn into cancer?

It’s extremely rare for a benign cyst to become cancerous. However, any chronic or recurrent Bartholin mass should be carefully monitored, especially if it changes character or persists despite treatment.

Are Bartholin gland cancers aggressive?

Some subtypes, like adenoid cystic carcinoma, tend to recur locally and spread along nerves. Others may progress more rapidly. Early detection remains critical for better outcomes.

Is recurrence common after treatment?

Yes. Local recurrence can occur even years later. Patients need long-term follow-up with regular exams and imaging to detect any return of disease early.

What’s the survival rate for Bartholin gland cancer?

When caught early and treated effectively, survival rates are high. In advanced cases or with lymph node involvement, prognosis depends on response to treatment and cancer subtype.

How often should women be screened for this cancer?

There is no routine screening test. However, any Bartholin mass in a woman over 40 should be biopsied. Awareness and timely evaluation are the most effective strategies.

Does this cancer affect sexual function?

Yes, particularly if extensive surgery is needed. Vaginal narrowing, pain, or scarring may occur. Rehabilitation and sexual health support are often essential parts of survivorship care.

Can this condition cause pelvic or back pain?

In advanced cases, yes. A growing tumor can invade nearby nerves or structures, leading to discomfort in the pelvis or lower back. Back ache bowel cancer — to illustrate similar mechanisms of pain syndrome.

Are there similar rare cancers in other organs?

Yes. For example, prostate cancer and breast cancers can present with subtle or misinterpreted signs. Prostate cancer screening and Axillary lump breast cancer to highlight the importance of early detection.