Back Ache and Bowel Cancer: Understanding the Overlap

- When Back Pain Could Signal Something More Serious

- Anatomy of the Bowel and Its Proximity to the Spine

- Early Symptoms of Bowel Cancer and the Role of Back Pain

- Differentiating Muscular Back Pain from Cancer-Related Discomfort

- Advanced Bowel Cancer and Spinal Metastases

- Diagnostic Workflow for Back Pain in Suspected Bowel Cancer

- Red Flags in Back Pain That Warrant Oncologic Evaluation

- Shared Symptoms Between Bowel Cancer and Other Malignancies

- Treatment Approaches When Bowel Cancer Presents with Back Pain

- Palliative Strategies and Symptom Control in Advanced Cases

- Rehabilitation and Functional Recovery After Oncologic Treatment

- Comparative Summary: Benign vs Malignant Back Pain

- The Role of Gut Microbiota and Inflammation in Pain Perception

- Genetic Syndromes Linking Bowel Cancer and Neurological Symptoms

- Patient Stories and the Importance of Early Recognition

- Lifestyle Choices and Preventive Strategies for At-Risk Individuals

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

When Back Pain Could Signal Something More Serious

Back pain is one of the most common medical complaints across all age groups. For many, it stems from mechanical issues, poor posture, muscular strain, or degenerative spine conditions. However, persistent or unexplained back pain—especially when not relieved by rest or physical therapy—can occasionally indicate a deeper underlying condition such as bowel cancer. Although bowel cancer typically presents with gastrointestinal symptoms, back ache may become a significant secondary complaint, particularly in advanced stages.

When a tumor grows large enough to press against nearby structures like the lower spine or sacral nerves, or if it spreads to the bones, back pain can emerge as a dominant symptom. This is often misinterpreted initially, leading to delayed diagnosis. Therefore, recognizing red flags—such as unexplained weight loss, changes in bowel habits, rectal bleeding, or fatigue in combination with chronic back discomfort—is essential for early intervention.

Anatomy of the Bowel and Its Proximity to the Spine

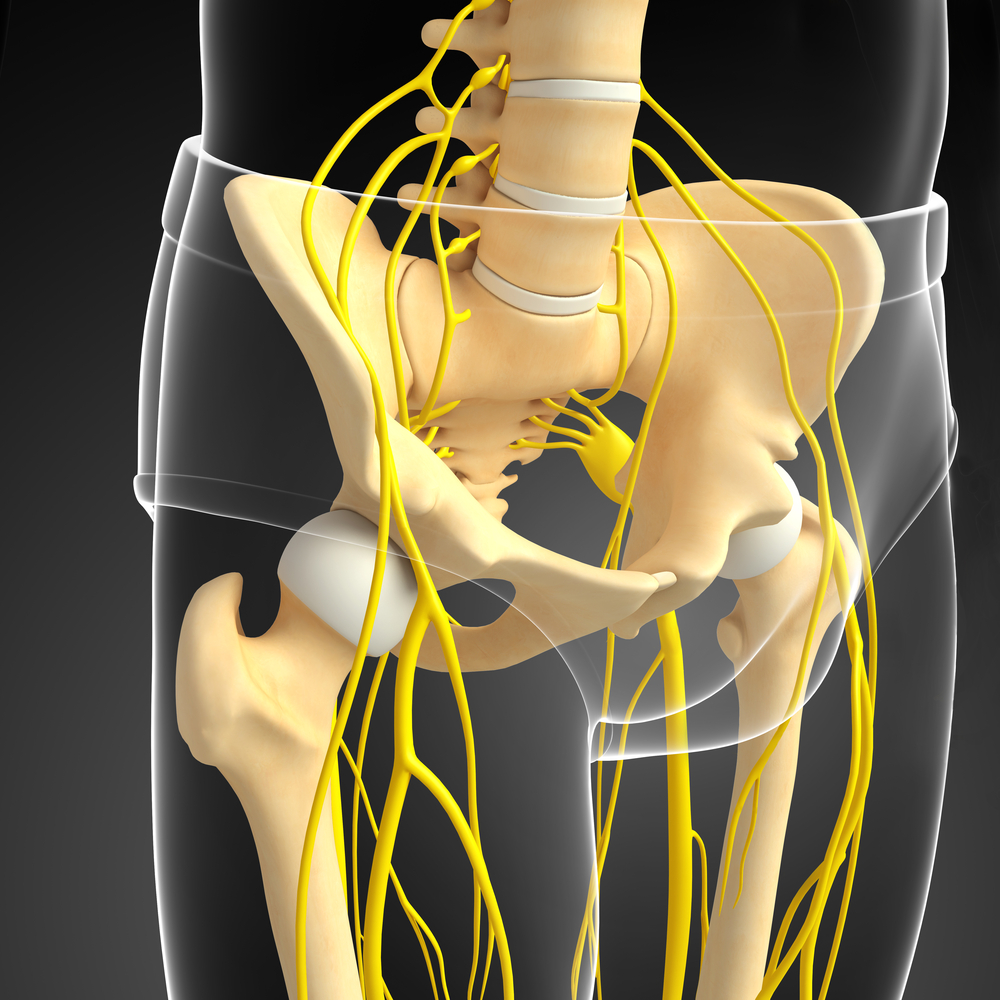

To understand how bowel cancer can cause back ache, it’s necessary to explore the anatomical relationship between the intestines and the spine. The colon, particularly the sigmoid and rectal regions, is located close to the lumbar vertebrae, pelvic bones, and sacrum. When tumors develop in the lower bowel, they can encroach upon the surrounding musculoskeletal and neural structures.

In cases of rectal or sigmoid colon cancer, pain may radiate to the lower back due to direct invasion or inflammatory response. Moreover, tumors in the retroperitoneal region—where part of the colon is situated—can exert pressure on nerves and cause referred pain, which is perceived as originating from the back, not the abdomen.

Patients may also experience secondary complications like abscess formation, peritoneal spread, or lymph node enlargement, all of which can exacerbate pressure on posterior structures. This proximity helps explain why back pain, though non-specific, may sometimes be the earliest physical manifestation of a deeply seated malignancy.

Early Symptoms of Bowel Cancer and the Role of Back Pain

Bowel cancer often begins silently. In early stages, it might cause only mild symptoms—or none at all. However, when signs do appear, they typically involve digestive disturbances: altered bowel habits (constipation or diarrhea), a sense of incomplete evacuation, or visible blood in the stool. Yet in certain patients, especially those with tumors in the lower rectum or pelvis, a deep, dull ache in the lower back may accompany these gastrointestinal complaints.

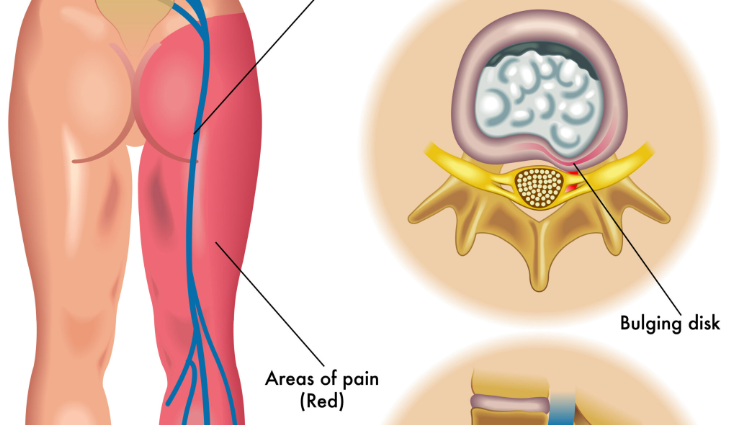

This pain can result from a growing tumor irritating the pelvic floor, sacral nerves, or lumbar plexus. It may worsen when sitting or lying down and is rarely relieved by standard analgesics or chiropractic intervention. Many patients seek treatment for their back first, unaware that the true cause lies within the bowel.

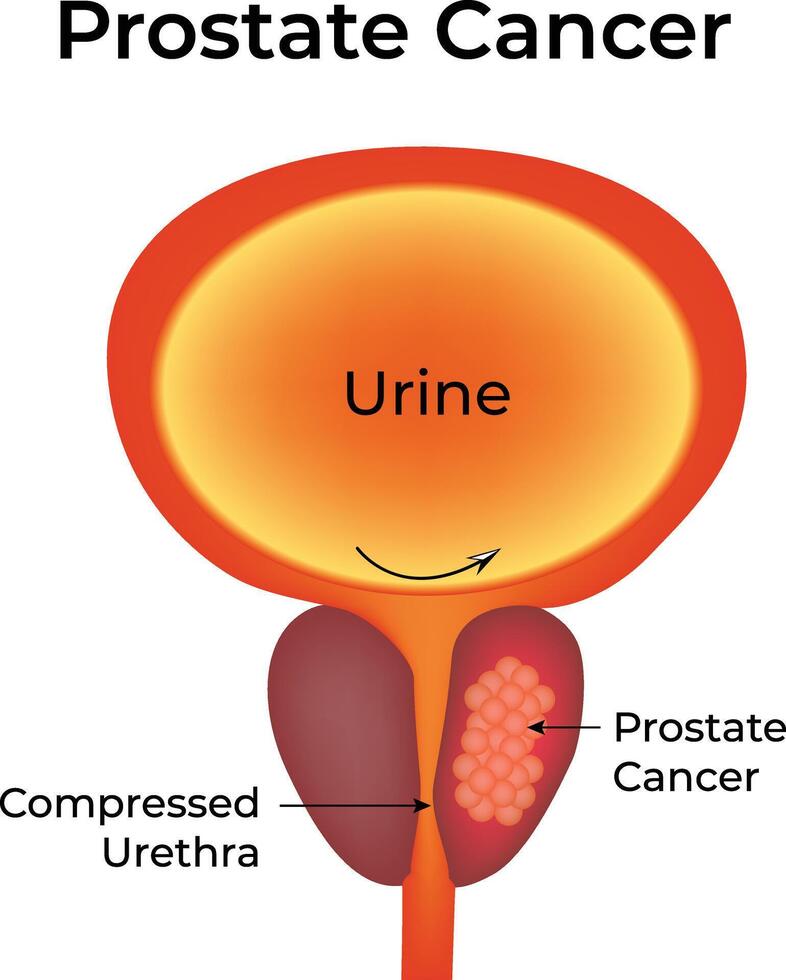

This overlap of symptoms can make diagnosis difficult and contributes to delays in referral to gastroenterology or oncology specialists. That’s why persistent back pain with unexplained gastrointestinal signs should always be investigated thoroughly, even in patients with no known family history or prior colorectal issues. Prostate cancer screening, especially in the context of distinguishing sources of pelvic and low back pain in men.

Differentiating Muscular Back Pain from Cancer-Related Discomfort

Distinguishing between benign back pain and that associated with bowel cancer is crucial but not always straightforward. Muscular back pain tends to vary with movement, posture, or physical exertion. It typically improves with rest, heat, or anti-inflammatory medications. Cancer-related pain, on the other hand, is usually more constant, deeper, and resistant to conventional therapy. It may be worse at night or early in the morning and often lacks a clear mechanical trigger.

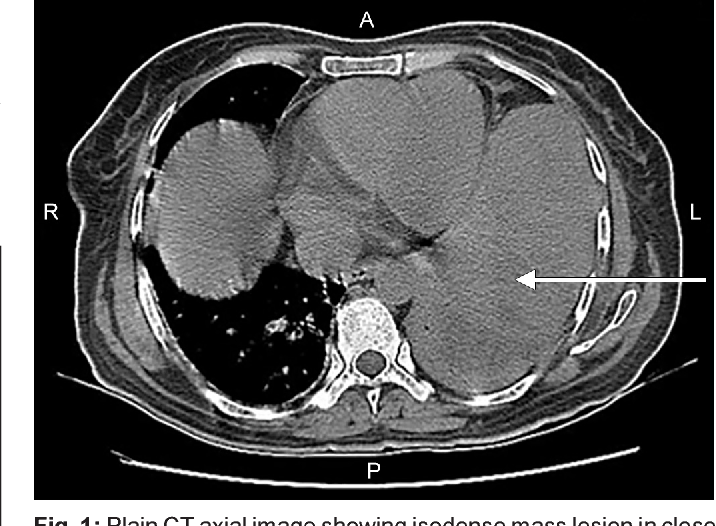

Patients with malignancy-related back pain may also exhibit systemic symptoms—such as anemia, unexplained fatigue, or unintentional weight loss. Neurological signs, like numbness or tingling in the legs, can develop if the tumor compresses nerves near the spinal cord. Imaging studies such as CT scans, MRI, or PET-CT are often necessary to identify the exact source and nature of the pain.

By paying attention to the characteristics and duration of the discomfort, clinicians can better differentiate mechanical from malignant causes. Unfortunately, misdiagnosis is common in the early stages, particularly when back pain is treated in isolation without considering gastrointestinal evaluation.

Advanced Bowel Cancer and Spinal Metastases

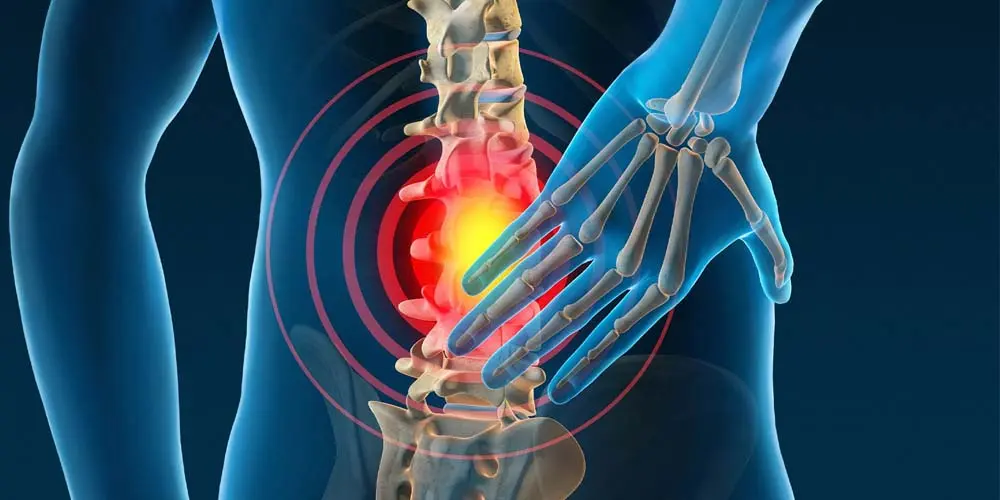

As bowel cancer progresses, it may metastasize to distant organs and tissues. One of the more serious but less commonly discussed complications is spinal metastasis. When cancer cells spread from the bowel to the vertebrae—most frequently in the lumbar spine—they can cause persistent back pain, often severe and unrelenting. This type of pain typically worsens over time and may be accompanied by neurological deficits such as weakness, numbness, or even bowel or bladder dysfunction.

Spinal metastases occur more often in later stages of colorectal cancer and are often a sign of systemic spread, along with liver or lung involvement. Once spinal structures are affected, the stability of the spine can be compromised, increasing the risk of pathological fractures and spinal cord compression. These events require urgent intervention to preserve function and prevent paralysis.

Treatment strategies include radiation therapy, targeted chemotherapy, and in some cases, surgical stabilization of the affected vertebrae. Early recognition of metastatic spread through back pain symptoms can lead to quicker intervention and potentially better outcomes.

Diagnostic Workflow for Back Pain in Suspected Bowel Cancer

When a patient presents with persistent back pain along with gastrointestinal symptoms, a structured diagnostic approach is essential. The first step includes a thorough history and physical exam, with attention to weight loss, bowel habits, appetite changes, and systemic fatigue. If the clinical picture raises suspicion, laboratory tests such as complete blood count, CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen), and fecal occult blood testing may follow.

Imaging plays a central role. Abdominal and pelvic CT scans help visualize bowel masses and their proximity to spinal structures. MRI is especially valuable for evaluating spinal nerve involvement or bony metastasis. In certain cases, a colonoscopy is required to visualize and biopsy any suspicious lesions in the colon or rectum directly.

Because back pain is often treated conservatively at first, it’s critical for clinicians to reevaluate symptoms that persist beyond 4–6 weeks, particularly when red flags are present. Cross-disciplinary coordination between gastroenterologists, radiologists, and oncologists can significantly expedite diagnosis. Axillary lump breast cancer in the context of discussion of metastatic diagnosis and clinical presentations beyond expected anatomy.

Red Flags in Back Pain That Warrant Oncologic Evaluation

While back pain is a frequent complaint in primary care, certain features should prompt immediate investigation for malignancy. These include pain that doesn’t improve with rest, progressive worsening over weeks, night pain that disrupts sleep, and neurological signs like numbness or tingling in the legs. Additional red flags include unexplained weight loss, fatigue, and iron-deficiency anemia.

A history of cancer, even if seemingly unrelated, raises the index of suspicion. In older adults, or patients with known colorectal polyps or inflammatory bowel disease, new onset back pain must be viewed with caution. It is often these non-specific signs that lead to delayed diagnosis, as they overlap with more benign musculoskeletal disorders.

These warning signs warrant expedited referral for imaging, lab tests, and, in some cases, endoscopy or biopsy. The earlier cancer is detected, the more options are available for curative treatment and symptom relief.

Shared Symptoms Between Bowel Cancer and Other Malignancies

Back pain is a symptom that spans multiple cancer types. For example, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer can also present with lower back discomfort due to direct invasion or metastatic spread. The overlap can complicate the diagnostic process and delay proper treatment.

Among men, differentiating back pain caused by prostate cancer versus bowel cancer is especially important, as both can metastasize to the spine and present similarly. Clinical distinction often requires careful PSA screening, imaging, and digital rectal examination.

Similarly, breast cancers—particularly aggressive subtypes like angiosarcoma—can cause atypical metastasis and must be considered in systemic back pain with widespread symptoms. Angiosarcoma breast cancer within the framework of broad oncological differentiation.

Understanding the broader oncologic context helps providers remain vigilant when assessing patients whose back pain resists standard musculoskeletal treatment approaches.

Treatment Approaches When Bowel Cancer Presents with Back Pain

When bowel cancer presents with back ache, treatment must address both the underlying malignancy and the pain symptoms that interfere with daily life. The primary oncologic treatment depends on the stage and location of the tumor and may include surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiation, or a combination. In cases where cancer has spread to the spine or surrounding nerves, pain control becomes a critical part of the care plan.

Multimodal pain management strategies may include opioids, nerve blockers, NSAIDs, or even corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and pressure on nerves. Interventional pain procedures such as epidural injections or nerve ablation might also be considered in select patients. If structural damage to the spine is confirmed, orthopedic or neurosurgical consultation for spinal stabilization could be necessary.

Addressing both tumor burden and quality-of-life concerns requires close collaboration between oncology, palliative care, pain management, and rehabilitation specialists. This integrative model ensures that patients don’t just survive but retain function and dignity during treatment.

Palliative Strategies and Symptom Control in Advanced Cases

In patients with advanced bowel cancer and significant spinal involvement, the treatment approach often shifts toward palliation—managing symptoms to improve comfort rather than aiming for cure. Back ache in these patients can become debilitating, limiting mobility, independence, and sleep. In such cases, palliative radiation directed at bone metastases may effectively reduce pain and tumor load in the spine.

Palliative chemotherapy may still be employed to slow disease progression, but its use is weighed against potential side effects. Strong analgesics, including morphine or fentanyl, are typically introduced alongside laxatives and supportive medications to balance pain control with gastrointestinal side effects.

Other supportive interventions include physiotherapy, mobility aids, and emotional counseling, all of which are essential in improving patient well-being. Family support and caregiver education also play a central role. In some cases, home hospice care becomes appropriate to ensure patients receive dignity-centered, compassionate care in their final weeks.

Rehabilitation and Functional Recovery After Oncologic Treatment

For patients who undergo successful treatment of bowel cancer—especially when spinal symptoms are involved—rehabilitation becomes vital. Physical therapy can help restore strength, flexibility, and endurance that may have declined due to pain, immobility, or systemic effects of cancer treatment. Particular focus is placed on core strength, posture correction, and safe ambulation.

Occupational therapy may also assist with adaptations at home and reintroduction to daily tasks. Pain management may continue as a long-term component of care, often using a tapered regimen of medications or complementary therapies like acupuncture, massage, or guided movement exercises.

Many survivors also benefit from psychological support, especially if chronic pain or disability lingers after treatment. The goal of rehabilitation is not only to restore physical function but also to help survivors reintegrate into meaningful daily life with a sense of control and purpose.

Comparative Summary: Benign vs Malignant Back Pain

| Feature | Benign (Musculoskeletal) | Malignant (Cancer-Related) |

| Onset | Often sudden, related to activity or strain | Gradual, progressive, not clearly triggered |

| Relieved by Rest/Positioning | Usually improves with rest or positional changes | Typically unrelieved, may worsen at night |

| Response to Medication | Good response to NSAIDs, heat, or stretching | Poor or temporary relief from standard therapies |

| Associated Symptoms | Muscle tightness, localized soreness | Weight loss, fatigue, neurological signs |

| Duration | Resolves in days to weeks | Persists or worsens over weeks/months |

| Imaging Findings | Normal spine or degenerative changes | Mass, metastasis, nerve compression |

| Laboratory Tests | Usually normal | Anemia, elevated CEA, other tumor markers |

This comparison helps patients and clinicians distinguish between typical mechanical back pain and warning signs that may point toward malignancy, such as bowel cancer. It underscores the importance of not ignoring persistent or unexplained symptoms, especially when systemic signs are present.

The Role of Gut Microbiota and Inflammation in Pain Perception

Emerging research suggests that gut microbiota and chronic low-grade inflammation may influence how patients perceive pain, including back pain associated with bowel cancer. Tumors in the colon or rectum can disrupt the local immune environment, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, which sensitize pain receptors not only in the gut but also along the spine.

The gut-brain axis—an intricate communication system involving the enteric nervous system, vagus nerve, and immune pathways—plays a critical role in this interaction. Alterations in gut flora due to cancer, poor nutrition, or chemotherapy may exacerbate systemic inflammation, resulting in widespread pain amplification.

Understanding this interplay helps explain why some bowel cancer patients report diffuse back or pelvic pain even in the absence of overt metastasis. It also opens the door to adjunctive therapies aimed at modulating the gut microbiome to reduce inflammation and improve overall pain control.

Genetic Syndromes Linking Bowel Cancer and Neurological Symptoms

Some patients with bowel cancer carry hereditary genetic syndromes that not only predispose them to malignancy but also to neurological symptoms, including back pain. One example is Lynch syndrome, which increases the risk of colorectal cancer and can also affect the brain and spinal cord through secondary neoplasms or metastatic behavior.

Another example is familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), where hundreds of polyps develop in the colon, with extracolonic manifestations including spinal abnormalities and soft tissue tumors. Though rare, these syndromes reinforce the importance of a detailed family history when assessing unexplained back pain, especially in younger patients.

Genetic testing and counseling can help identify at-risk individuals, allowing for enhanced screening protocols, prophylactic measures, and better surveillance of both cancer and pain-related complications.

Patient Stories and the Importance of Early Recognition

A growing number of patient narratives reveal how back pain was the first or only symptom of their bowel cancer diagnosis. In several cases, patients underwent months of physical therapy or chiropractic care with no relief, only to later discover a tumor pressing against spinal or pelvic structures. These stories highlight the danger of misattribution and the delay it can cause in initiating proper treatment.

Hearing real experiences from survivors or families affected by late-stage bowel cancer emphasizes the value of clinical suspicion and early endoscopic evaluation. It also underscores the emotional toll of missed diagnoses—something healthcare professionals and patients alike must work together to reduce through better communication, awareness, and holistic symptom analysis.

Lifestyle Choices and Preventive Strategies for At-Risk Individuals

While not all cases of bowel cancer are preventable, certain lifestyle changes can significantly reduce the risk of both cancer and associated complications like back pain. Maintaining a fiber-rich diet, limiting processed meats, exercising regularly, and avoiding smoking and excess alcohol have all been linked to reduced colorectal cancer incidence.

Routine colonoscopy screening, starting at age 45 (or earlier for high-risk individuals), remains one of the most effective ways to catch precancerous polyps before they progress. Patients with chronic back pain of unknown origin should also consider whether digestive symptoms are being overlooked or underreported.

Public health education that connects common symptoms—such as persistent back ache—with potentially serious diseases like bowel cancer is critical. Empowering individuals to seek timely evaluation, even when symptoms seem unrelated, can improve survival and quality of life outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Can back pain really be an early sign of bowel cancer?

Yes, although rare, persistent lower back pain—especially when accompanied by digestive symptoms—can be an early sign of colorectal cancer. Tumors in the pelvic or retroperitoneal area may press on nerves or surrounding tissues, causing referred pain in the back.

How is cancer-related back pain different from muscular pain?

Cancer-related back pain is typically deep, dull, and constant. It often doesn’t improve with rest, stretches, or physical therapy, and may worsen at night. Muscular pain tends to be more localized and responds well to conservative treatment.

What part of the bowel is most likely to cause back pain when affected by cancer?

The rectum and sigmoid colon are anatomically closest to the lower back and pelvis. Tumors in these regions are more likely to irritate or compress nerves, potentially leading to lower back pain.

Is it common for bowel cancer to spread to the spine?

It’s not common in early stages, but in advanced colorectal cancer, metastasis to the spine can occur. This often results in persistent pain, nerve compression, and mobility issues, requiring urgent treatment.

What should I do if I have both back pain and changes in bowel habits?

If these symptoms persist for more than a few weeks, seek medical evaluation. A combination of gastrointestinal symptoms and unexplained back ache should not be ignored and may warrant imaging and colonoscopy.

Can bowel cancer cause nerve pain or sciatica-like symptoms?

Yes. If a tumor presses on the lumbar plexus or sacral nerves, patients may feel shooting or radiating pain down the legs, similar to sciatica. This is more common in locally advanced or metastatic disease.

Which tests can help determine if back pain is related to cancer?

suspicion

Does back pain from bowel cancer ever improve with treatment?

Yes. If the tumor is surgically removed or effectively reduced with chemotherapy or radiation, related back pain often improves significantly. Pain management and rehabilitation also aid recovery.

Can bowel cancer cause upper back pain?

While less common, cancers that spread to the thoracic spine or upper retroperitoneal structures can lead to upper back discomfort. This is more typical in late-stage disease.

Is it possible to misdiagnose bowel cancer-related back pain?

Unfortunately, yes. Many cases are initially mistaken for musculoskeletal issues, especially in younger patients. This can delay diagnosis, which is why red flags like weight loss or anemia are critical to investigate.

Can lifestyle changes reduce cancer-related back pain risk?

Yes. Preventing colorectal cancer through diet, exercise, and screening reduces the likelihood of complications like back pain. A strong core and musculoskeletal health may also improve resilience against secondary symptoms.

Is chemotherapy effective against back pain from metastases?

In many cases, yes. Chemotherapy can shrink tumors pressing on spinal structures, relieving pain. It’s often combined with palliative radiation or surgical stabilization if structural integrity is compromised.

Should I see a gastroenterologist or spine specialist first?

If your back pain is accompanied by digestive symptoms, a gastroenterologist may be appropriate. However, a multidisciplinary team including oncologists, spine surgeons, and pain specialists is ideal if cancer is confirmed.

Can back pain occur even before bowel symptoms start?

Yes. In some patients, particularly those with tumors pressing on nerves or growing retroperitoneally, back pain may precede visible bowel changes by weeks or months.

Are there other cancers that cause similar back pain?

Absolutely. Prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, and breast cancers like angiosarcoma can all cause lower back discomfort via local spread or distant metastasis.