Anal Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide for Patients and Caregivers

- What Is Anal Cancer and How Common Is It?

- Key Causes and Risk Factors Behind Anal Cancer

- Early Symptoms and Why They’re Often Misdiagnosed

- Understanding the Staging of Anal Cancer

- Diagnostic Procedures: How Anal Cancer Is Confirmed

- The Role of HPV in the Development of Anal Cancer

- Treatment Options: From Localized to Advanced Disease

- Prognosis and Survival Rates: What to Expect

- Managing Side Effects of Treatment

- Lifestyle Adjustments During and After Therapy

- Follow-Up Care and Surveillance Plans

- Comparing Anal Cancer with Other HPV-Related Cancers

- Anal Cancer and Quality of Life: Emotional and Social Considerations

- Comparative Risk Table: Anal Cancer vs. Other Cancers

- Integrating HPV Vaccination and Cancer Prevention

- Living Beyond Anal Cancer: Survivorship and Long-Term Outcomes

- FAQ

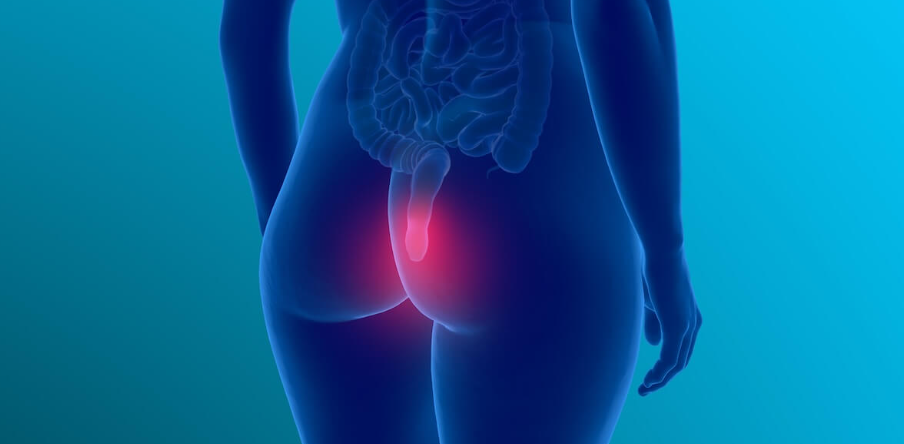

What Is Anal Cancer and How Common Is It?

Anal cancer is a relatively rare type of cancer that originates in the tissues of the anus, which is the opening at the end of the rectum through which stool exits the body. Unlike colorectal cancer, which arises higher in the digestive tract, anal cancer has unique cellular origins and behavior. It most commonly begins in the squamous cells lining the anal canal. While it accounts for less than 3% of all gastrointestinal tract cancers, its incidence has been rising, particularly in populations with specific risk factors like HPV infection. Understanding its nature as a separate clinical entity is crucial for timely diagnosis and effective treatment planning.

Key Causes and Risk Factors Behind Anal Cancer

The primary cause of anal cancer in most cases is persistent infection with high-risk types of the human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18. These strains are well-documented in their ability to induce cellular changes that may eventually lead to malignant transformation. Other contributing risk factors include a history of receptive anal intercourse, chronic immunosuppression (such as in HIV-positive individuals), smoking, and a history of cervical, vulvar, or vaginal cancer. Additionally, individuals with untreated anal warts or chronic anal inflammation have an increased likelihood of developing this condition. The interplay of viral, environmental, and immunological components highlights the multifactorial nature of anal carcinogenesis.

Early Symptoms and Why They’re Often Misdiagnosed

Early symptoms of anal cancer can be subtle and are often mistaken for less serious conditions such as hemorrhoids or fissures. These may include anal bleeding, itching, pain or pressure, and the presence of a palpable mass. Because these symptoms mimic benign anorectal disorders, many patients delay seeking medical attention, which can lead to diagnosis at a more advanced stage. A persistent change in bowel habits, particularly a feeling of incomplete evacuation, may also occur. Recognizing these signs early—and distinguishing them from common gastrointestinal complaints—requires both clinical suspicion and appropriate diagnostic follow-up.

Understanding the Staging of Anal Cancer

Staging is vital in determining both prognosis and the appropriate treatment approach. The TNM system is used to classify anal cancer, where T refers to the size and local extent of the tumor, N describes lymph node involvement, and M indicates the presence of distant metastases. For instance, a T1 tumor is confined and small (<2 cm), while T4 indicates invasion into nearby organs such as the vagina, urethra, or bladder. Lymphatic spread is a common early feature of anal cancer, particularly to the inguinal and pelvic nodes. Understanding the stage helps oncologists assess whether local treatment (e.g., chemoradiation) is sufficient or whether systemic therapies are needed.

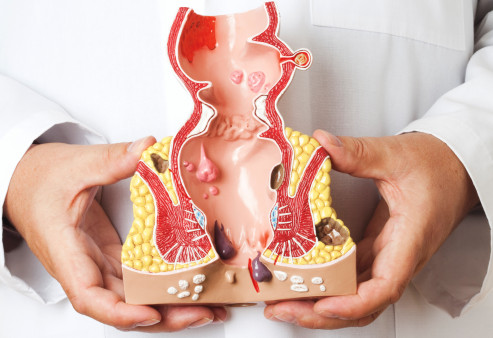

Diagnostic Procedures: How Anal Cancer Is Confirmed

Diagnosing anal cancer involves a combination of physical examinations, imaging studies, and histopathological confirmation. Initial evaluation often begins with a digital rectal exam (DRE), where a physician palpates the anal canal for irregularities. If suspicious lesions are found, an anoscopy or proctoscopy may be used to provide direct visualization of the anal lining. A biopsy is essential to confirm malignancy, revealing the cellular architecture and confirming whether the cancer is squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type. Imaging techniques such as MRI and CT scans are employed to assess local invasion and lymph node involvement, while PET scans are used to evaluate for distant metastasis. It’s important to note that for patients with HIV or HPV, more frequent screening may be necessary due to elevated risk profiles.

The Role of HPV in the Development of Anal Cancer

High-risk HPV strains play a central role in the pathogenesis of anal cancer. The virus infects the epithelial cells lining the anal canal and can cause precancerous lesions known as anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN). Over time, and particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems, these lesions may progress to invasive cancer. HPV-16 is implicated in the majority of cases and is also found in cervical, oropharyngeal, and vulvar cancers. This viral link has profound implications for prevention: the HPV vaccine has shown promise in reducing the incidence of HPV-related anal lesions and may ultimately reduce cancer incidence. The strong correlation between HPV and anal cancer also reinforces the importance of regular screening for high-risk individuals, particularly men who have sex with men and immunocompromised populations.

Treatment Options: From Localized to Advanced Disease

Treatment of anal cancer typically involves a multidisciplinary approach. For most patients, the standard treatment is a combination of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, often referred to as chemoradiation. This regimen is effective in preserving anal function and avoiding the need for surgery. Chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin-C are commonly used. For small, well-defined tumors without nodal involvement, radiation alone may suffice. In advanced or recurrent cases, surgical options like abdominoperineal resection (APR) may be considered, although this procedure results in permanent colostomy. Immunotherapy and targeted biological agents are also being explored for cases unresponsive to conventional therapies. Personalized treatment plans are based on tumor staging, patient health, and the presence of comorbid conditions.

Prognosis and Survival Rates: What to Expect

The prognosis for anal cancer has improved significantly over the past decades, largely due to advancements in treatment and early detection. Survival rates vary depending on the stage at diagnosis. For localized tumors (Stage I or II), the 5-year survival rate can be as high as 80%. In cases where regional lymph nodes are involved, the survival drops slightly but remains favorable with appropriate treatment. Advanced disease with distant metastases has a significantly lower survival rate, generally around 30% at five years. However, outcomes also depend on other factors such as HIV status, overall immune function, and treatment tolerance. Long-term follow-up care is essential, as recurrences may happen even after successful primary treatment.

Managing Side Effects of Treatment

Patients undergoing treatment for anal cancer often experience a wide range of side effects that can significantly impact their quality of life. The most common include fatigue, skin irritation around the anus from radiation, and gastrointestinal symptoms like diarrhea or rectal bleeding. Chemotherapy can also lead to nausea, lowered immunity, and mouth sores. These effects are not just physically taxing but emotionally draining, especially when treatment spans several weeks. Supportive care plays a key role here: managing hydration, diet modifications, the use of topical creams for radiation burns, and antiemetics for nausea. Patients should be encouraged to report side effects early, allowing providers to intervene before symptoms worsen. Holistic care strategies, including counseling, physical therapy, and integrative medicine, may also help mitigate treatment-related distress.

Lifestyle Adjustments During and After Therapy

Throughout treatment and recovery, lifestyle changes become essential not just for healing but for long-term wellness. Patients are often advised to follow a nutrient-rich diet high in fiber and low in processed foods to support gut health and maintain regular bowel movements. Gentle physical activity, such as walking or stretching, can alleviate fatigue and enhance mood. Stress-reduction techniques—meditation, guided breathing, or journaling—may improve mental resilience. Patients should avoid smoking and limit alcohol intake, as both can interfere with healing and increase recurrence risk. Post-treatment, ongoing monitoring and adapting one’s daily routines around bowel function, fatigue, or pain management can dramatically improve the quality of life and support long-term remission.

Follow-Up Care and Surveillance Plans

Once initial treatment is completed, structured follow-up care becomes a cornerstone of long-term management. Surveillance typically includes regular physical examinations, anoscopy, and imaging studies to monitor for signs of recurrence. For the first two years, visits may occur every 3 to 6 months, then space out depending on stability. Blood tests may not detect recurrence directly but can help monitor overall health. Patients with a history of HPV-related disease may also undergo periodic screening for other HPV-associated cancers, including cervical or oropharyngeal types. Follow-up care isn’t just about recurrence; it’s about detecting and managing late side effects, maintaining psychological health, and optimizing survivorship.

Comparing Anal Cancer with Other HPV-Related Cancers

Although anal cancer shares a viral etiology with several other cancers, it differs in presentation and clinical behavior. For example, cervical and anal cancers both originate in squamous cells and are driven by HPV-16 and HPV-18, but the anatomical differences affect screening approaches and symptom recognition. Oropharyngeal cancer, another HPV-related type, presents with swallowing issues or throat pain rather than rectal symptoms. Interestingly, the connection between HPV and skin lesions in animals, such as salivary gland cancer in dogs, shows how viral oncology spans species boundaries (вставить ссылку здесь). Understanding these distinctions helps guide tailored treatment plans and reinforces the value of HPV vaccination across genders and populations.

Anal Cancer and Quality of Life: Emotional and Social Considerations

The emotional toll of anal cancer can be significant, especially given the location of the disease and its associated stigma. Many patients feel embarrassment or shame, which may prevent open conversations with loved ones or delay seeking medical help. Social anxiety, altered body image, sexual dysfunction, and fear of recurrence are common. These concerns can lead to depression or social withdrawal if not properly addressed. Psychosocial support—including therapy, peer groups, and online communities—can provide essential relief. Partners and caregivers also need education to offer effective support. Open communication with healthcare providers about fears, intimacy concerns, and emotional fatigue should be encouraged throughout treatment and beyond.

Comparative Risk Table: Anal Cancer vs. Other Cancers

| Feature | Anal Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | Cervical Cancer | Lung Cancer |

| Common Cause | HPV, immunosuppression | Diet, age, genetics | HPV | Smoking, pollutants |

| Screening Routine | No standard for all | Colonoscopy | Pap smear | Chest X-ray, CT scan |

| Common Symptoms | Rectal bleeding, anal pain | Blood in stool, change in habits | Vaginal bleeding, pain | Cough, chest pain, weight loss |

| Five-Year Survival Rate (avg.) | ~65% | ~65% (stage-dependent) | ~66% (localized) | ~20% (all stages) |

| Treatment Modalities | Chemoradiation, surgery | Surgery, chemo, targeted | Surgery, radiation, chemo | Chemo, radiation, immunotherapy |

This table helps patients understand where anal cancer fits in the broader oncology landscape, and why early detection and tailored care are crucial for better outcomes.

Integrating HPV Vaccination and Cancer Prevention

Vaccination against the human papillomavirus (HPV) is one of the most powerful tools for preventing anal cancer and other HPV-associated malignancies. The HPV vaccine, typically administered in adolescence, protects against the high-risk strains most frequently implicated in anal, cervical, and oropharyngeal cancers. Even for adults, catch-up vaccination can offer benefits, especially for those at increased risk such as men who have sex with men or immunocompromised individuals. Discussions around the vaccine should include dispelling myths, emphasizing safety, and highlighting its role in cancer prevention. A growing body of evidence also links HPV with immune-related complications in less common cancers, prompting broader interest in viral oncogenesis, as seen in topics like can cancer cause low phosphate levels.

Living Beyond Anal Cancer: Survivorship and Long-Term Outcomes

Survivorship is not just about being cancer-free—it’s about rebuilding a meaningful, healthy life after diagnosis and treatment. Long-term anal cancer survivors may still face physical challenges such as bowel incontinence, chronic pain, or sexual dysfunction. Emotional scars may persist, including health anxiety or fear of stigma. Survivorship care plans help by providing structured support for nutrition, exercise, ongoing screenings, and mental health resources. Many survivors find purpose in advocacy or peer mentorship, helping others navigate a path they’ve already walked. As with other cancer types, such as lung cancer metastasis to breast, survivorship care demands long-term planning and cross-disciplinary coordination.

FAQ

What are the first symptoms of anal cancer?

The earliest signs of anal cancer often include rectal bleeding, a sensation of a lump near the anus, or persistent anal itching. Many people initially mistake these symptoms for hemorrhoids or minor irritation, which can delay diagnosis. If these signs persist or worsen, medical evaluation is essential for early detection and improved treatment outcomes.

Is anal cancer related to HPV?

Yes, the majority of anal cancer cases are strongly linked to infection with high-risk strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV-16. The virus can cause mutations in the cells lining the anal canal, eventually leading to precancerous changes and, over time, malignancy. HPV vaccination is an effective preventive strategy.

Can anal cancer be cured?

When diagnosed at an early stage, anal cancer is highly treatable and often curable. Standard treatment usually involves chemoradiation, which can be effective in destroying the tumor without the need for surgery. For more advanced stages, additional treatments may be necessary, but remission is still possible in many cases.

How is anal cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosis typically begins with a physical examination, followed by an anoscopy or sigmoidoscopy to visually inspect the anal canal. A biopsy of any suspicious lesion is required to confirm cancer. Imaging such as MRI, CT, or PET scans may then be used to stage the disease and determine the extent of its spread.

Who is most at risk for anal cancer?

Individuals at highest risk include those with persistent HPV infections, people with weakened immune systems (such as HIV-positive individuals), men who have sex with men, and those with a history of cervical or other HPV-related cancers. Smoking and older age also increase the likelihood of developing anal cancer.

What does treatment for anal cancer involve?

The mainstay of treatment is combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy, which offers high cure rates while preserving the sphincter. Surgery is usually reserved for cases that do not respond to initial treatment or for recurrent tumors. Patients may also receive supportive therapies to manage side effects.

Is surgery always necessary for anal cancer?

No, most early to moderately advanced cases of anal cancer are treated effectively with chemoradiation, making surgery unnecessary. However, if the tumor persists or recurs after initial treatment, surgical removal, including abdominoperineal resection (APR), may be considered as a secondary option.

What are the side effects of treatment?

Treatment side effects may include fatigue, skin irritation, rectal discomfort, diarrhea, and urinary difficulties. Long-term side effects can involve bowel dysfunction, sexual complications, or pelvic pain. Side effects vary by individual and can often be managed with supportive care.

Can anal cancer return after treatment?

Yes, recurrence is possible, particularly within the first few years after treatment. Regular follow-up appointments, including physical exams and imaging when needed, are essential for monitoring. Early detection of recurrence can significantly improve the chances of successful intervention.

Is anal cancer contagious?

No, cancer itself is not contagious. However, the HPV virus linked to anal cancer is sexually transmissible. This makes preventive strategies like condom use and HPV vaccination important in reducing risk across the population.

Can anal cancer spread to other parts of the body?

Yes, in advanced cases, anal cancer can metastasize to nearby lymph nodes, the liver, lungs, or other organs. Staging evaluations are performed at diagnosis to assess whether metastasis has occurred, and treatment plans are adjusted accordingly.

How common is anal cancer?

Anal cancer is relatively rare, accounting for less than 3% of all gastrointestinal cancers. However, its incidence has been gradually increasing, particularly among high-risk groups such as older adults and those with chronic HPV infections.

What is the survival rate for anal cancer?

The five-year survival rate depends on the stage at diagnosis. For localized disease, survival is around 80%, while more advanced disease that has spread to lymph nodes or distant organs sees significantly lower rates. Early detection remains the most important factor for prognosis.

Can anal cancer affect younger individuals?

While most common in people over 50, anal cancer can also affect younger individuals, especially those with immune suppression or long-term HPV infection. The availability of the HPV vaccine offers a preventative opportunity for younger populations.

Are there ways to prevent anal cancer?

Prevention strategies include HPV vaccination, regular screening for high-risk individuals, practicing safe sex, and smoking cessation. Awareness of early symptoms and timely medical evaluation are also essential in preventing progression from precancerous changes to full malignancy.