Tick-Borne Diseases: Emerging Threats in a Changing Climate

What’s the Deal with Tick-Borne Diseases?

Ever come back from a hike and found an unexpected tiny hitchhiker on your leg? Maybe it was just a harmless bug—or maybe it was a tick. But how much do you actually know about what ticks can carry?

Tick-borne diseases are no longer just rare conditions you hear about in passing. They’re becoming more common—and in places where they never used to be a concern. It’s part of the broader story of how our changing environment is fueling the emergence of once-overlooked pathogens, not unlike how Oropouche virus has quietly expanded its footprint beyond the Amazon basin.

Tick-borne diseases are no longer just rare conditions you hear about in passing. They’re becoming more common—and in places where they never used to be a concern. So why is this happening now?

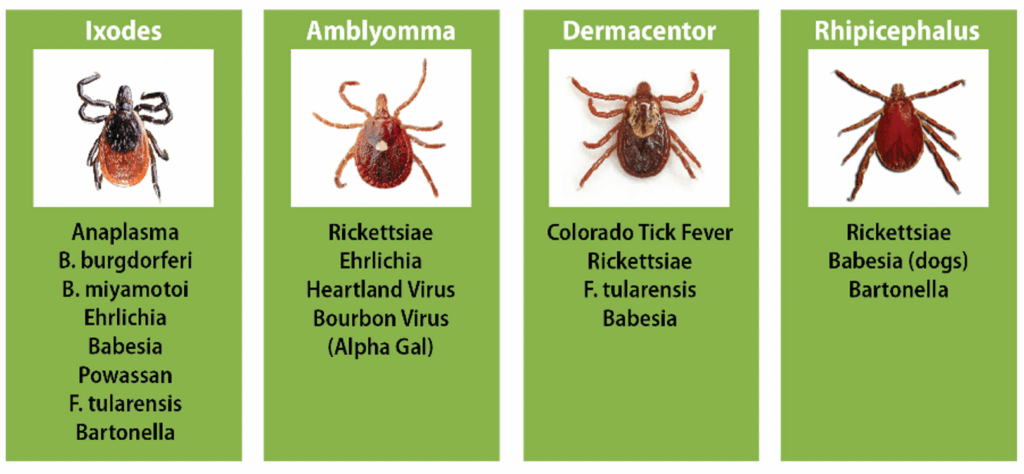

Let’s start with the basics. Ticks are small arachnids (yep, like spiders) that feed on the blood of animals—and sometimes humans. When they bite, they can transmit bacteria, viruses, and even parasites straight into the bloodstream. That sounds scary, and in some cases, it is. Diseases like Lyme disease, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and babesiosis can have serious health effects if left untreated.

But here’s where things get even more interesting—and a bit worrying. The environment is changing. Climate shifts, warmer winters, longer growing seasons… they’re all playing a role in helping ticks thrive and spread to new areas. Ticks that used to be confined to certain forests or elevations are now showing up in people’s backyards. Could that explain the sudden surge in tick-related illnesses? And what about those of us who live in cities—are we safe?

So the real question is: are we prepared for this? Do we recognize the signs early enough? Do we know how to protect ourselves?

These are just a few of the questions we’ll explore as we take a deeper look into the world of tick-borne diseases—what causes them, how they affect us, and what we can do to stay one step ahead.

What Can You Actually Catch from a Tick?

So, what are we really dealing with here? When someone says they got “a tick bite,” what’s the worst that could happen? Most people have heard of Lyme disease, but is that the only concern? Not even close.

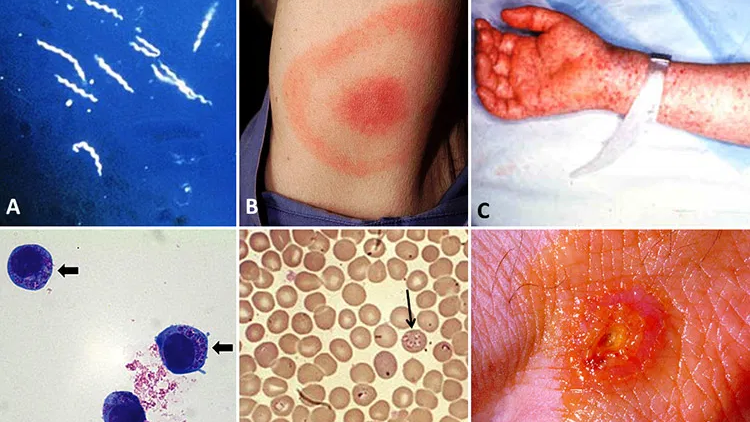

Let’s start with Lyme, since it’s the name that tends to dominate headlines. Did you know it’s the most common tick-borne illness in North America? It’s caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium called Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted mainly by the blacklegged tick, also known as the deer tick. If caught early, it can usually be treated with antibiotics—but if it’s missed? That’s when things can get complicated. We’re talking joint pain, nervous system issues, and long-term fatigue that can linger for months.

And Lyme isn’t alone. Rocky Mountain spotted fever, babesiosis, anaplasmosis, ehrlichiosis—the list of tick-borne threats continues to grow. Some of these diseases overlap in symptoms, and others, like Borrelia miyamotoi, have only recently entered the diagnostic spotlight.

Even more concerning is that ticks don’t just spread one disease at a time. Co-infections are a real and rising threat, particularly as surveillance struggles to keep up. This patchy visibility mirrors the broader diagnostic challenges we see in diseases with pandemic potential, such as the hypothetical but plausible “Disease X” that has become a priority in global preparedness conversations.

Ever heard of Rocky Mountain spotted fever? The name sounds like it belongs in a cowboy movie, but it’s actually one of the deadliest tick-borne diseases in the U.S. It’s caused by a bacterium called Rickettsia rickettsii, and if it’s not treated quickly, it can lead to serious organ damage. Oddly enough, despite the name, it’s now more commonly found in the southeastern and south-central U.S. So the geography has shifted—why do you think that is?

Then there’s anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis—two diseases with names that seem ripped from a medical textbook. They both attack your white blood cells, and while they’re usually less severe than Rocky Mountain spotted fever, they can still cause fever, fatigue, and in some cases, life-threatening complications. Are these on your doctor’s radar when you come in with a summer fever?

Let’s not forget babesiosis. This one’s caused by a parasite—not a bacterium or virus—that invades your red blood cells, kind of like malaria. It can be particularly dangerous for older adults or people with weakened immune systems. And yes, it’s been spreading, especially in the Northeast.

And here’s a twist: not all tick-borne diseases are even well understood yet. New ones are emerging—ever heard of Borrelia miyamotoi? Probably not. It’s a close cousin of the Lyme bacterium and has only recently started to appear on the radar. What else could be lurking in the tick microbiome that we haven’t even identified?

Ticks also vary by region. In the U.S. alone, you’ll find different species like the Lone Star tick, the American dog tick, the Gulf Coast tick—each one with its own preferred hosts and disease threats. So it really does matter where you are and which tick bit you. Could a simple camping trip from Massachusetts to Missouri change your risk profile completely?

It all raises some important questions: Are we paying enough attention to these tiny carriers of disease? And as their habitats grow thanks to warmer temperatures and shifting wildlife patterns, are we ready for what’s coming next?

How Does a Tiny Bite Do So Much Damage?

Okay, let’s get into the nitty-gritty—how does a tick bite actually make you sick? It’s just a little nip from a bug, right? So how does that turn into weeks or even months of fatigue, joint pain, fever, or worse?

Here’s where things get surprisingly sophisticated. Ticks aren’t just passive passengers carrying germs. They’re more like sneaky biological syringes. When a tick latches onto your skin, it doesn’t just bite and go. It anchors itself with a tiny, barbed mouthpart and starts feeding—slowly, for hours or even days. During that time, it’s releasing saliva that numbs the bite site, thins your blood, and—most importantly—hides it from your immune system. Pretty clever, right?

But here’s the catch: that same saliva can also carry a whole cocktail of pathogens. Bacteria, viruses, parasites—they can all be passed from the tick into your bloodstream while you’re completely unaware. No sting, no itch, no obvious sign. So by the time you realize something’s wrong, the invader might already be making itself at home.

Let’s talk specifics. Take Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium behind Lyme disease. Once it enters your body, it doesn’t just stay in one place—it moves. It travels through your tissues, evades your immune defenses, and even changes its surface proteins to stay hidden. Imagine a spy that keeps changing disguises. How do you fight that?

And what does your immune system do in response? Well, sometimes it fights back aggressively. But sometimes, the response itself causes problems—think inflammation, overreaction, tissue damage. That’s why some people with tick-borne illnesses feel worse after the infection seems to be gone. Is it the lingering bacteria—or your own immune system still throwing punches?

Now think about other pathogens like Babesia, which invades red blood cells, or Rickettsia, which targets the lining of your blood vessels. Each one has its own preferred method of infiltration and attack. How do you diagnose a disease when the symptoms can be so broad—or when multiple pathogens are working together? (Yes, ticks can transmit more than one disease at a time. How’s that for a plot twist?)

Here’s a big question: if these microbes are so crafty, are we doing enough to keep up with them? Are our diagnostic tools and treatments keeping pace with what’s happening at the microscopic level?

The pathogenesis—the biological story of how these diseases unfold—is still being written. And as new species of ticks spread into new regions, bringing unfamiliar pathogens with them, we’re probably going to be rewriting that story a lot more than we expect.

What Does It Actually Feel Like to Have a Tick-Borne Disease?

Let’s say you got bitten by a tick last weekend on that camping trip. Now it’s a few days later. You’re feeling off. Headache, maybe a bit of fever. Nothing too dramatic—but enough to make you pause. Is it just a summer cold? Did you overdo it in the heat? Or is your body trying to warn you?

This is where things get complicated. Tick-borne diseases often start with vague symptoms—fatigue, muscle aches, chills, maybe a rash or a low-grade fever. The kind of stuff most of us shrug off. But here’s the tricky part: depending on the disease, things can escalate quickly. Or… they can simmer quietly and then erupt weeks—or even months—later.

Let’s go back to Lyme disease for a second. The classic sign is the “bull’s-eye” rash, right? Except, here’s the surprise: not everyone gets it. In fact, a significant chunk of people infected with Lyme never develop that telltale red ring. So if you don’t see it, are you in the clear? Not necessarily.

Without treatment, Lyme can morph. What starts as a mild flu-like illness can progress to joint swelling, shooting nerve pain, facial paralysis (called Bell’s palsy), and even heart rhythm abnormalities. And in some people, symptoms linger long after the infection is treated—a controversial condition often referred to as “chronic Lyme”. Is it lingering bacteria? Immune dysfunction? Something else entirely? Researchers still don’t fully agree.

Other tick-borne diseases bring their own special brand of trouble. Rocky Mountain spotted fever can lead to a full-body rash, severe abdominal pain, and even coma if it isn’t treated early. Babesiosis might start out mild but can spiral into life-threatening anemia or organ failure in older adults or those with weak immune systems. Anaplasmosis and ehrlichiosis can look like just another viral illness—until they don’t.

And here’s a curveball: what if you get infected with more than one pathogen from a single tick bite? Co-infections can confuse the picture even more, and standard treatment for one illness might not cover the others. So how does your doctor know what to test for? Do they even think to look?

It’s no wonder tick-borne diseases are so frequently misdiagnosed—or dismissed altogether. Fatigue, brain fog, mood swings, joint pain—these can easily be chalked up to stress, aging, or a vague “post-viral syndrome.” How many people are walking around with undiagnosed tick-borne illness, thinking they’re just tired or unlucky?

So the big questions are: What are we missing? Are doctors trained to spot these diseases early enough? And how do we navigate a world where the symptoms can be so broad, so sneaky, and sometimes… so long-lasting?

Why Is It So Hard to Get a Straight Answer?

So you’re not feeling right. You’re tired all the time, maybe achy in weird places, your brain’s a little foggy. You’ve got this nagging sense that something’s off. You go to the doctor. Blood tests are ordered. Maybe you even mention that you were hiking a few weeks ago and think you might’ve gotten a tick bite—though you’re not totally sure. And then? Everything comes back “normal.”

Now what?

Welcome to the frustrating world of diagnosing tick-borne diseases. It’s not as simple as checking a single box or running one test. In many cases, even when someone has a tick-borne illness, the early blood work might not show it. Why? Because your body hasn’t had time to mount a detectable immune response yet. Or worse—maybe it has, but the test doesn’t catch it.

Let’s take Lyme disease as an example again. The standard diagnostic tool is a two-step test: first an ELISA test, and if that’s positive, a Western blot to confirm. But here’s the catch—these tests don’t look for the bacteria itself. They look for antibodies your body makes against the bacteria. And those can take weeks to show up. So if you test too early, you might get a false negative. How many people walk away thinking they’re fine, only to worsen later?

Even later-stage tests can be murky. What happens if you still have symptoms, but the test is “technically” negative? Does that mean you’re imagining it? Or is it that our testing just isn’t sensitive enough?

For other diseases like anaplasmosis or ehrlichiosis, doctors might use a PCR test to look directly for the bacterial DNA, but again—timing is everything. Catch it too late or too early, and the test may miss it. Same with babesiosis: it often requires a blood smear under a microscope, which sounds precise but can be very easy to miss if not done carefully. And who’s doing that kind of careful lab work in a busy ER?

Plus, what if you’re infected with multiple pathogens at once? Will your provider even think to test for more than one disease? Do most routine panels even check for rarer or newer tick-borne illnesses like Borrelia miyamotoi or Heartland virus?

Then there’s the imaging question. Some patients with neurological symptoms may end up getting MRIs or brain scans—looking for lesions, inflammation, anything to explain the mysterious fog or numbness. But what happens if the imaging looks totally normal? Do you get sent to a neurologist, a rheumatologist, or a therapist?

Here’s a question we need to ask more often: Are we diagnosing the person—or just the test result?

There’s a growing recognition that current diagnostic tools are far from perfect. Some researchers are pushing for better direct detection methods, like high-resolution sequencing or new biomarker panels that can catch infections earlier and more reliably. But how soon will these tools be available in everyday clinics—not just research labs?

So the next time someone says, “The test came back negative,” it might be worth asking: Was it the right test? At the right time? And interpreted the right way?

So You’ve Got a Tick-Borne Disease—Now What?

Alright, let’s say you’ve made it through the maze. You got the right diagnosis. The doctor confirmed it—maybe Lyme, maybe anaplasmosis, maybe even a combination of a few things (because, of course, ticks don’t like to keep things simple). So what’s next?

Well, for most bacterial tick-borne diseases, the first line of defense is antibiotics—usually doxycycline. And if you start treatment early, the outlook is generally pretty good. But here’s a question: what happens if you didn’t catch it early?

Late-stage Lyme, for example, may not respond as quickly—or as completely—to antibiotics. Some symptoms, especially neurological ones, might linger. And that leads to a much bigger and murkier conversation about what people often refer to as “chronic Lyme” or post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. But here’s the catch: not everyone agrees on what that actually means—or what to do about it.

Is it an ongoing infection that antibiotics didn’t fully clear? Is it a sort of immune system glitch, where your body keeps reacting even after the invader is gone? Or is it something else entirely? And more urgently—what are you supposed to do if you’re still sick after your treatment ends?

Doctors don’t always have clear answers. Some patients bounce back quickly, while others are left managing lingering symptoms: fatigue, brain fog, muscle pain, anxiety. Sound familiar? It’s no wonder many of these patients are passed between specialists, trying to figure out if what they’re experiencing is “real” or if it’s just “in their head.” (Spoiler: it’s real.)

Then there’s babesiosis, which is caused by a parasite—not a bacterium—so doxycycline alone doesn’t cut it. Treatment usually involves a combination of antiparasitic and antibiotic medications, like atovaquone and azithromycin. But that combo doesn’t work for everyone, especially those with compromised immune systems. What if you’re in that category?

Supportive care also matters. Fever management, hydration, rest—but what happens if “rest” stretches into months of missed work, missed school, missed life? Is there a plan for that? Are there specialists who really understand what you’re dealing with?

And what about the cost—physically, emotionally, financially? Some treatments aren’t covered by insurance, especially when they fall into the gray areas of chronic illness. How does someone navigate that when they can barely get out of bed?

There’s also the risk of re-infection. Unlike with some viruses, getting Lyme once doesn’t protect you from getting it again. So even if you’ve been through the whole ordeal, one more tick bite can start the whole cycle over. Are we telling people that enough?

Ultimately, the treatment path can look very different from person to person. Which raises an uncomfortable but important question: are we trying to treat tick-borne diseases as if they’re one-size-fits-all when they’re clearly not?

Can You Actually Avoid Getting Bitten?

Let’s be honest—ticks aren’t exactly the stuff of nightmares. They don’t fly. They don’t buzz in your ear. They’re tiny, quiet, slow-moving. So how is it that something so small can cause such a huge health headache?

That’s what makes prevention feel a bit tricky, right? If ticks were bigger or louder, we’d probably be a lot more careful. But instead, they wait in the brush, on tall grasses and low shrubs, with their little hooked legs outstretched, ready to grab onto the next passing ankle. That’s called “questing,” by the way. Ever think about how something the size of a sesame seed has a hunting strategy?

So—how do you avoid being the next meal?

First, there’s the personal protection side: long sleeves, tucking pants into socks, insect repellents with DEET or picaridin, and doing full-body tick checks after time outdoors. Sounds simple enough. But how many people actually dothose things consistently? Especially when it’s hot out, or when you’re just sitting on a picnic blanket that doesn’t looklike it’s crawling with ticks?

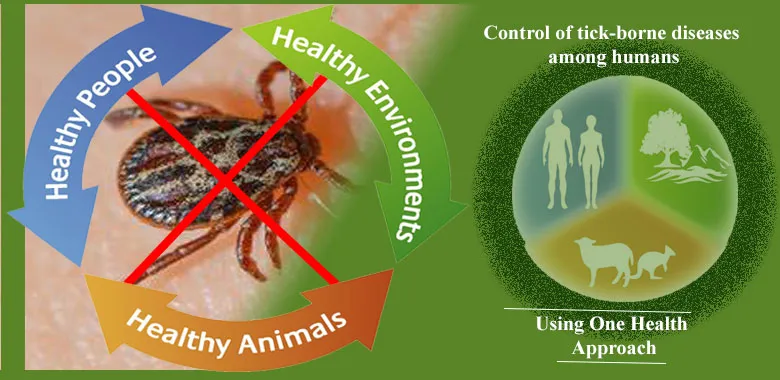

And what about pets? Dogs are tick magnets. If they’re not on tick prevention meds, they can carry ticks into your house without you realizing it. Suddenly, your cozy couch is a risk zone. Did you even think to check behind your dog’s ears or under the collar after your walk?

Then there’s the environmental angle. You can “tick-proof” your yard by clearing brush, creating wood chip barriers, and keeping grass short. Some people even go as far as installing deer fences—since deer are major hosts for ticks. But who’s really doing all that? And what about public parks, trails, and shared green spaces? Who’s responsible there?

And here’s the bigger-picture question: with ticks expanding their range because of climate change, what does prevention look like on a community or national level? Should we be spraying large areas with tick-control substances? What about the impact on pollinators and other insects? Are there eco-friendly solutions we’re overlooking?

Some scientists are exploring vaccine options—not just for humans, but for reservoir animals like mice that spread Borrelia. Others are working on targeted genetic interventions, like sterilizing ticks or disrupting their ability to carry pathogens. Exciting stuff, but how soon will that actually make a difference for someone planning a weekend hike?

And while we’re asking tough questions—are we doing enough to educate people? Most folks don’t realize that tick season can start in the spring and last well into fall. Or that you can get bitten while raking leaves, gardening, or even just sitting outside in certain regions. Prevention isn’t just about deep wilderness treks—it’s about everyday awareness.

So maybe the real question is this: what would it take for us to treat tick prevention with the same seriousness we give to sunscreen or seat belts?

What’s New—and What’s Next?

So, we’ve talked about how tricky tick-borne diseases are to catch, diagnose, and treat. But what if things are starting to change? What if we’re finally starting to catch up?

In the last couple of years—especially between 2025 and 2026—there’s been a flurry of new research, some of it exciting, some of it… let’s just say, a little alarming.

Let’s start with the science. One of the biggest breakthroughs? Next-generation diagnostic tools. We’re talking about multi-pathogen PCR panels and AI-enhanced blood analysis that can detect multiple infections from a single sample—and do it faster, even before full-blown symptoms appear. Think of it like moving from dial-up to fiber-optic speed, but for lab work. Could this finally be the solution for patients who’ve been bouncing around undiagnosed for months?

There’s also growing interest in metabolomics and immune profiling—basically reading your body’s unique “chemical signature” when it’s reacting to an infection. Imagine a future where instead of just testing for specific bacteria, doctors could read your body’s entire immune story and tell whether you’ve been exposed, infected, or are still recovering. Are we on the edge of a diagnostic revolution?

But while the lab tools are catching up, the ticks themselves aren’t slowing down. If anything, they’re evolving and spreading even faster.

Just in the past year, researchers have confirmed new populations of the Asian longhorned tick in regions of the U.S. where it hadn’t been seen before. This particular species is especially worrisome—it reproduces asexually (yep, no need for males), and it can transmit multiple pathogens. Could this tick become the next big public health threat?

And there’s more: new pathogens are being discovered. One recently identified virus, tentatively called “Sundown Virus,” has been found in both ticks and rodents in the upper Midwest. It’s too early to know how dangerous it is—but do we ever find these things early enough to get ahead of them?

Public health agencies are paying attention. There’s been a surge in federal funding for tick surveillance and regional tick-mapping programs. Mobile apps are even helping people report tick encounters in real time, helping researchers track movement patterns. But is that happening fast enough to match how quickly tick habitats are shifting?

There are also whispers in the research community of a new Lyme disease vaccine entering late-stage trials. This one’s designed to target not just the human immune response, but also disrupt how the tick transfers the pathogen in the first place. Could it work? Could it last? And more importantly, will people trust it enough to take it?

One more thing to think about: are healthcare providers getting the training they need to keep up with all these changes? Having better tools is great—but what happens if doctors don’t know when or how to use them?

From rapid diagnostic panels to experimental vaccines, tick-borne research is finally gaining traction. Yet, even with breakthroughs, the gap between discovery and real-world impact remains wide. New threats—like the Asian longhorned tick or the tentatively named “Sundown Virus”—suggest this story is far from over.

In many ways, this mirrors the lessons learned from tracking emerging coronaviruses like HKU5-CoV-2—a virus still in bats, but exhibiting genetic traits that demand proactive monitoring. Whether it’s a tick or a bat, early action beats late response every time.

So, here we are in 2025—with better tech, more data, smarter prevention strategies, and… new threats just over the horizon. It’s progress, sure—but it’s also a race. And the question is: are we gaining ground fast enough to stay ahead of the next tick bite?

Tick-Borne Diseases: FAQ

Q: How dangerous is a tick bite, really?

A tick bite might seem minor, but depending on the species and how long it’s attached, it can transmit bacteria, viruses, or parasites directly into your bloodstream. Some of these infections can become serious or even life-threatening if not diagnosed and treated early.

Q: Can I still get sick even if I never saw a tick?

Yes. Many people never notice the bite. Ticks are tiny—some as small as a poppy seed—and can attach in hard-to-see places. They’re also silent and painless while feeding.

Q: What tick-borne diseases should I actually be concerned about?

Lyme disease is the most well-known, but others like Rocky Mountain spotted fever, babesiosis, anaplasmosis, and ehrlichiosis are also significant—and increasing. There are even newly emerging diseases like Borrelia miyamotoi and the recently identified Sundown Virus.

Q: Why are tick-borne diseases becoming more common?

Climate change, suburban sprawl, and shifting wildlife patterns are all helping ticks spread to new regions. Longer warm seasons and milder winters are allowing ticks to thrive in places they never did before.

Q: What does it feel like to have a tick-borne disease?

Symptoms vary, but common ones include fatigue, joint or muscle aches, fever, chills, and sometimes rashes or neurological issues. Some people develop chronic or long-lasting symptoms even after treatment.

Q: Why is it so hard to diagnose these illnesses?

Many tick-borne diseases mimic other conditions. Early tests can miss infections because your body hasn’t made enough antibodies yet. Co-infections or less common pathogens are often overlooked.

Q: What if I still feel sick after antibiotics?

That’s a growing concern. Some patients experience lingering symptoms—what’s often called post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. The cause is still debated, and treatment options are limited and not standardized.

Q: Can I get infected more than once?

Yes. Getting Lyme disease once doesn’t make you immune. If another infected tick bites you, you can get reinfected.

Q: What’s the best way to prevent tick bites?

Use insect repellent with DEET or picaridin, wear protective clothing, do tick checks after outdoor activity, and manage your environment (clear brush, keep grass trimmed). Pets should be on tick prevention too.

Q: Are there any new tools or treatments on the horizon?

Yes! Between 2025–2026, we’ve seen major improvements in diagnostics (like multi-pathogen testing and immune profiling), new vaccine trials, and better tick surveillance using mobile apps and genetic tracking. But access and awareness are still uneven.

Final Thoughts: So Where Do We Go From Here?

Tick-borne diseases are a growing reality—not a distant, rural concern but something showing up more often in suburbs, cities, and right in our backyards. They’re complex, often misunderstood, and evolving fast.

But here’s the good news: the more we learn, the more we can do. Awareness leads to earlier diagnosis. Earlier diagnosis means better outcomes. Better tools mean fewer mysteries. And public health strategies—when taken seriously—work.

So maybe the real message isn’t fear. It’s readiness.

Know the signs. Ask questions. Stay curious.

Because the more prepared we are, the less power we give to a creature no bigger than a sesame seed.