Measles: Resurgence of a Preventable Disease

- Part One — Introduction: So Why Are We Still Talking About Measles?

- Part Two — Virology and Pathogenesis: What Exactly Is the Measles Virus Doing in Your Body?

- Part Three — Epidemiology: How Did We Let Measles Sneak Back In?

- Part Four — Clinical Features: What Does Measles Actually Look Like in Real Life?

- Part Five — Diagnosis: How Do You Know It’s Measles and Not Just a Viral Rash?

- Part Six — Treatment: If There’s No Cure for Measles, What Can We Actually Do?

- Part Seven — Prevention: If We Know How to Stop Measles, Why Aren’t We Doing It?

- Part Eight — Recent Developments (2025–2026): Are We Learning Fast Enough — or Backsliding Further?

- FAQ: Measles — What People Are Still Asking

- Part Nine — Conclusion: What Now?

Introduction: So Why Are We Still Talking About Measles?

Let’s start with a simple question: How does a disease with a safe, effective vaccine continue to cause outbreaks in 2025? It’s a question that public health experts, doctors, and communities around the world are asking — with increasing urgency.

Measles isn’t just another childhood illness. It’s a highly contagious viral infection that can spread like wildfire in unvaccinated populations. Did you know that just one infected person can transmit the virus to 90% of the people around them if they’re unvaccinated? That makes it more infectious than the flu, and even more than COVID-19.

And yet — it’s entirely preventable.

The vaccine that protects against measles (you’ve probably heard of it as the MMR vaccine, which also covers mumps and rubella) has been around since the 1960s. It’s one of the most successful tools in modern medicine. So why are we seeing a resurgence?

Is it misinformation? Vaccine hesitancy? Gaps in healthcare access? The answer, as you might guess, isn’t simple — but it’s urgent.

Because measles doesn’t just mean a rash and a fever. It can lead to serious complications: pneumonia, encephalitis, even death. And those risks are especially high in young children and people with compromised immune systems.

So, in this series, we’re going to break it down. What exactly is the measles virus? How does it infect and spread? Why are we seeing outbreaks in places that once had it under control? And most importantly: what can be done about it — right now?

Let’s take a closer look.

Virology and Pathogenesis: What Exactly Is the Measles Virus Doing in Your Body?

Let’s get curious for a moment.

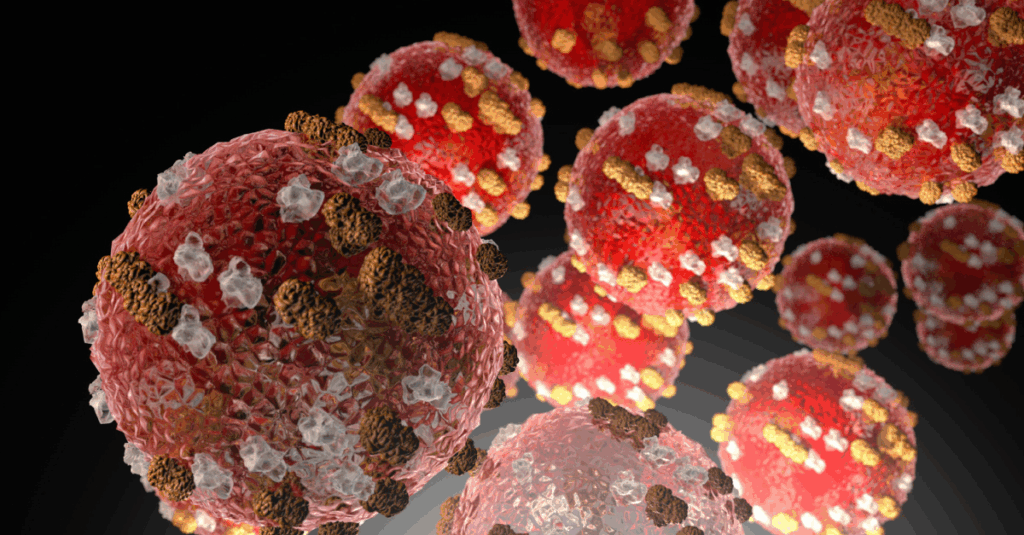

What actually is the measles virus? What does it look like under a microscope? How does something invisible to the naked eye make people so sick, so quickly?

At its core, the measles virus is a tiny bundle of RNA — a single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus, to be exact. It belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family, genus Morbillivirus. If you’re not deep into virology, that probably sounds like technical soup. But here’s the simpler version: this virus is a microscopic hijacker, built to invade, copy itself, and spread — fast.

So how does it start?

Usually, someone breathes it in. That’s all it takes. The virus travels through airborne droplets — maybe from a cough or sneeze — and finds its first home in the mucous membranes of your nose, mouth, or throat. From there, it makes a quick move to the local lymph nodes. That’s where it meets immune cells — and here’s the twist: instead of being destroyed by them, it actually infects them.

Wait — how does that happen?

Why doesn’t the immune system shut it down right away?

That’s part of what makes measles so cunning. It infects immune cells like macrophages and dendritic cells — the very ones that are supposed to detect and fight it. Once it’s inside, it uses them as a transport system, riding along to the lymphatic system and then into the bloodstream. This is called primary viremia — the first wave of viral spread.

But it doesn’t stop there. After a few days, it launches a second wave — secondary viremia — when it reaches organs and tissues throughout the body: the skin, the respiratory tract, the gut, even the brain. That’s when symptoms really start to kick in. The fever, the cough, the telltale rash? That’s your body in a full-scale battle.

And here’s the part that’s both fascinating and alarming:

Measles temporarily wipes out your immune memory.

For weeks, sometimes months, your body “forgets” how to fight off other diseases it once knew how to handle — like a rebooted computer that lost its files. This effect is called immune amnesia, and it’s part of why measles is so dangerous, even after you recover from the infection itself.

So why is understanding the virology important? Because it helps explain just how efficient — and destructive — the virus can be. It’s not just about the visible symptoms; it’s about what’s going on at a cellular level. And once you see that clearly, the stakes become even more obvious.

A virus this fast, this stealthy, and this damaging…

Why on earth would we let it spread when we have the tools to stop it?

Epidemiology: How Did We Let Measles Sneak Back In?

Here’s a question that’s hard to ignore:

If we had measles under control, why are we seeing outbreaks again?

To understand that, we need to take a step back and look at the big picture. Measles isn’t just a local issue — it’s a global one. And the story it tells is partly about biology, partly about behavior, and very much about the cracks in our public health systems.

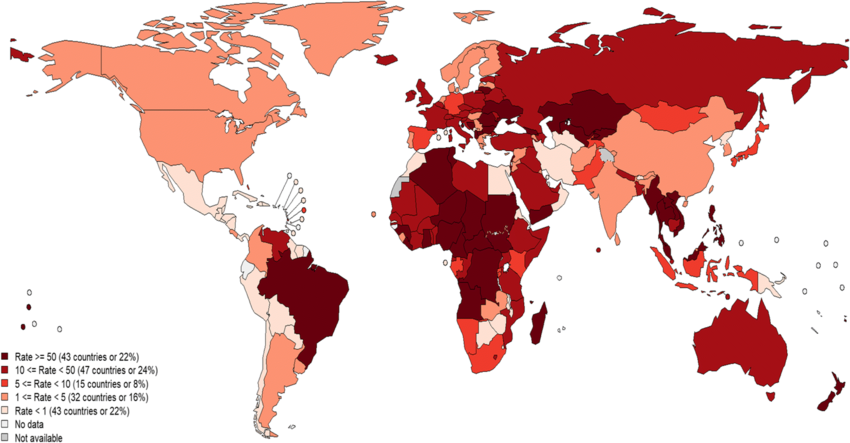

So, what does the global landscape look like?

Not that long ago, the world was celebrating milestones. In 2000, measles was declared eliminated in the United States — meaning there was no sustained transmission within the country. Other regions had made major progress too, thanks to aggressive vaccination campaigns and international efforts like the Measles & Rubella Initiative.

But fast forward to now, and we’re seeing a troubling reversal.

Why? What changed?

Let’s start with the numbers.

According to recent WHO reports, measles cases surged past 300,000 in 2024 — a significant jump from the previous year. And those are just the confirmed cases. Experts believe the actual numbers could be several times higher, especially in countries where reporting is inconsistent or healthcare access is limited.

But it’s not just happening in low-income nations. Surprisingly, outbreaks are re-emerging in places with advanced healthcare systems — including the U.S., U.K., and parts of Europe. So what’s driving that?

There isn’t one single answer — but there are some major culprits.

1. Vaccine hesitancy.

This one’s a big deal. Whether it’s due to misinformation, mistrust of institutions, or complacency, more and more people are delaying or skipping vaccines. And measles doesn’t need much of an opening — when fewer than 95% of people are vaccinated, the “herd immunity” shield starts to weaken. In some communities, that rate has dipped well below 90%.

2. Global disruption.

The COVID-19 pandemic threw routine immunization schedules into chaos. Clinics were shut down. Families stayed home. Resources were diverted. As a result, millions of children missed their scheduled MMR doses, especially in lower-income regions. That created a ripple effect we’re still seeing now.

The ripple effects of the pandemic are still playing out in the world’s immunization programs.

You may also be interested in our in-depth article on “COVID-19”, which dives into how global health disruptions have affected everything from vaccine confidence to infrastructure resilience — laying the groundwork for measles to slip back in.

3. Travel and migration.

Measles moves with people. One infected traveler can introduce the virus into a vulnerable community — especially if that community has gaps in vaccination coverage. It doesn’t matter if the virus originated across the world; in a matter of hours, it can be next door.

So the real question becomes:

How do we stop it from spreading further?

That’s the challenge. Because once an outbreak begins, controlling it requires fast response — contact tracing, emergency immunization drives, public communication, and sometimes school or event closures. It’s a race against time. And when healthcare systems are under strain, that race gets even harder to win.

We’re at a crossroads. On one side: we have the science, the vaccine, and decades of progress. On the other: social, political, and logistical barriers that let this virus regain ground.

What direction will we choose?

Clinical Features: What Does Measles Actually Look Like in Real Life?

Measles isn’t subtle. But it doesn’t start out that way.

To really understand what happens during a measles infection, it helps to look at it in stages — not just symptoms scattered across a checklist, but as a sequence of events that unfolds inside the body. It’s not just a rash. It’s a full-body invasion with some surprising twists.

So — let’s break it down.

1. Incubation Period (Silent, but Dangerous)

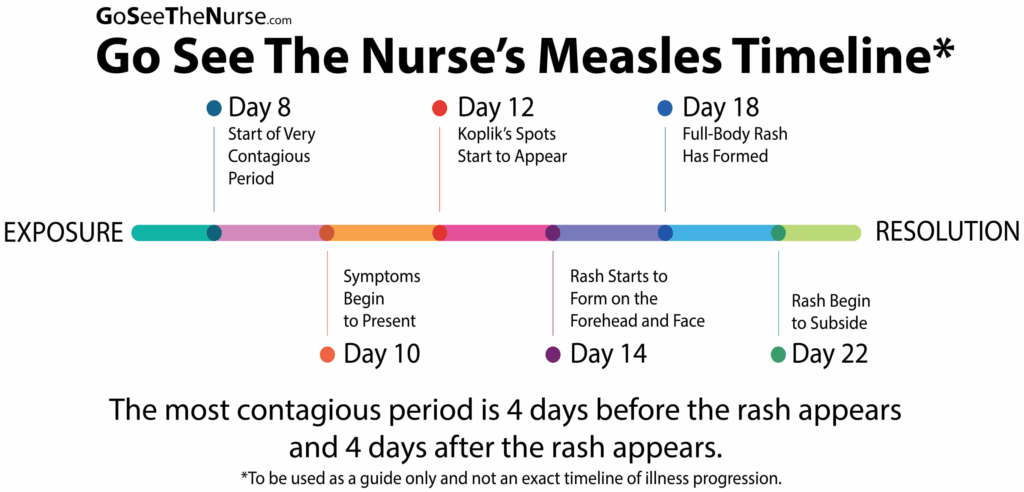

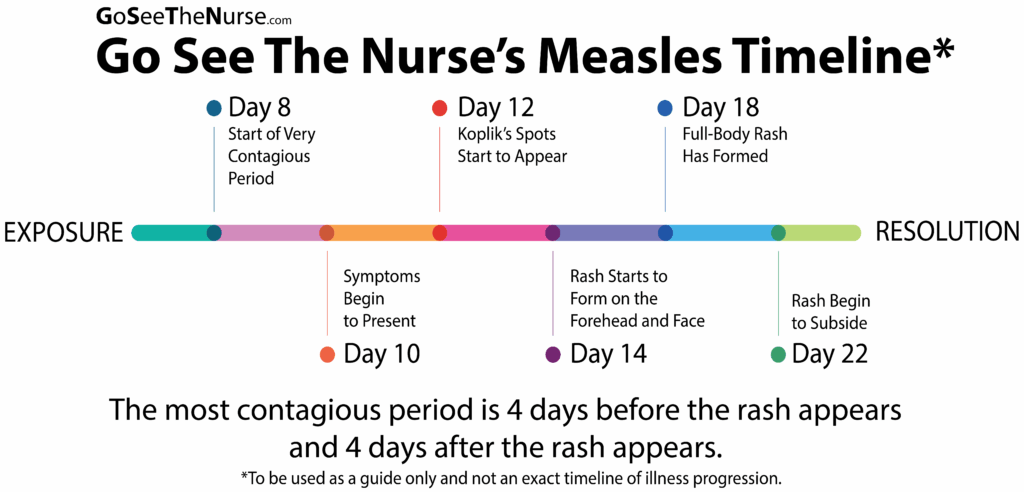

Duration: About 10 to 14 days after exposure

Here’s the sneaky part: after someone is exposed to the measles virus — say, through a cough or even breathing shared air — nothing happens. Not at first. They feel completely fine. But under the surface, the virus is busy replicating in the mucosal tissue and lymph nodes, slowly preparing for its big debut.

During this time, the virus travels through the bloodstream in what’s called primary viremia, eventually spreading to the skin, lungs, and other organs. The person has no idea they’re infected — and yet, they’re approaching their most contagious phase.

2. Prodromal Phase (It Looks Like a Bad Cold… Until It Doesn’t)

Duration: 2 to 4 days

This is the early symptomatic stage — and it’s incredibly easy to mistake for a regular upper respiratory virus. That’s part of why measles is so good at spreading. At this point, the person might experience:

- High Fever: Often the first sign. This isn’t a low-grade fever — temperatures can quickly climb above 102°F (39°C).

- Cough, Runny Nose, and Red Eyes (Coryza and Conjunctivitis): Classic symptoms, often appearing together. The eyes may become sensitive to light, and the cough can be persistent.

- Koplik Spots: These are tiny white spots inside the cheeks, near the molars — like grains of salt on a red background. They’re pathognomonic, meaning their presence almost definitively confirms measles. But they’re easy to miss if you’re not looking for them.

Most importantly?

The person is already contagious — starting about 4 days before the rash appears.

3. Rash Phase (The Body’s Alarming Red Flag)

Duration: About 4 to 7 days

Here’s where measles becomes unmistakable. The rash typically appears 3 to 5 days after the fever starts, and it follows a very characteristic pattern:

- Starts at the hairline or forehead and spreads downward to the face, neck, chest, and then the limbs. It often joins together (confluent) as it spreads.

- Maculopapular in nature — meaning it’s made up of flat, red areas (macules) with small raised bumps (papules).

- Accompanied by a worsening fever, sometimes exceeding 104°F (40°C). This is often when people feel the sickest, because the immune system is in full gear trying to fight off the virus.

Interestingly, the rash signals that the immune system is finally fighting back. Without an immune response, the rash wouldn’t appear — which is why severely immunocompromised people sometimes never develop it.

4. Recovery Phase — or Complications?

For some, the rash fades, the fever breaks, and the body begins to recover. But for others, the story takes a darker turn.

So let’s ask: What are the most serious complications of measles?

Complications of Measles: More Than Just a Rash

A. Pneumonia

This is the most common cause of measles-related death, especially in children. The virus weakens the respiratory system, making it easy for secondary bacterial infections to take hold. In some cases, the measles virus itself can cause viral pneumonia, which is more difficult to treat.

B. Encephalitis (Brain Inflammation)

Though rare (about 1 in every 1,000 measles cases), encephalitis can be devastating. Symptoms can include seizures, confusion, and loss of consciousness — and it may lead to permanent brain damage or death.

C. Diarrhea and Dehydration

Especially dangerous in young children and malnourished populations, measles can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms, leading to life-threatening dehydration.

D. Otitis Media (Ear Infections)

Measles often triggers middle ear infections, particularly in children. This might seem minor, but repeated infections can cause hearing loss if left untreated.

E. Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE)

This is one of the most tragic outcomes. SSPE is a rare, fatal brain disorder that appears years after the initial measles infection — typically in children who had measles before the age of two. It causes progressive neurological deterioration and always ends in death.

And Then There’s “Immune Amnesia”

This might be the most surprising part of all: measles doesn’t just weaken the body temporarily — it can erase years of immune memory. After recovering from measles, people are often more susceptible to other infections for up to 2–3 years. That means a child who once had immunity to pneumonia or strep may lose that protection — all because of measles.

This concept — called immune amnesia — helps explain why communities hit hard by measles often see a spike in other diseases afterward. It’s not just a measles outbreak — it’s a weakening of the immune wall for months, even years.

So What’s the Takeaway?

Measles isn’t just a rash. It’s a complex, systemic illness that attacks the body, hijacks the immune system, and leaves a dangerous ripple effect in its wake. For most people, it causes a few miserable days. For others, it opens the door to lifelong consequences — or worse.

So maybe the real question isn’t “What does measles look like?”

Maybe it’s: Why would we ever let it come back?

Diagnosis: How Do You Know It’s Measles and Not Just a Viral Rash?

Let’s be honest — at first glance, measles looks like a lot of other things. Fever, cough, rash… isn’t that half the pediatric textbook? So how do doctors actually pin it down? How do you move from suspicion to certainty, especially in the middle of cold and flu season — or in a place where measles hasn’t been seen in years?

It starts with clinical instinct — but that’s only the beginning.

Recognizing the Pattern

The first step in diagnosing measles is simply noticing the rhythm of it — that predictable, textbook-like unfolding of symptoms. It almost always begins with a few days of high fever, followed by a dry cough, runny nose, and irritated, red eyes. These symptoms by themselves don’t scream “measles,” but when they arrive together, in that particular order, they start to form a recognizable outline.

Then comes the rash — and that’s when the picture sharpens. It typically starts at the face and hairline and moves downward, covering the body in a kind of reddish wave. It’s not itchy like an allergy rash; it’s flat and bumpy, and it usually arrives when the fever is already peaking. That pattern — a top-down rash during high fever, not after — is a huge clinical clue.

And if you look closely inside the mouth, you might catch a glimpse of Koplik spots: tiny, bluish-white specks on a red background, sitting along the inner cheeks like little warning lights. They’re not always easy to spot, but when you see them, they’re as close to a diagnostic slam dunk as measles offers.

Asking the Right Questions

But symptoms alone aren’t enough. Diagnosing measles often depends just as much on what the patient doesn’t say. Have they been vaccinated? Have they traveled recently? Is there a known outbreak in their community or school? Have they been in contact with anyone who was sick?

Those seemingly small details matter enormously. In fact, in areas where measles has been mostly eliminated, travel history and vaccine status can make or break the diagnosis. An unvaccinated child with fever and rash who just came back from abroad? That’s a red flag. A vaccinated teen with no travel history and a faint rash? Less likely.

Confirming the Diagnosis in the Lab

Clinical suspicion is powerful — but when it comes to something as contagious as measles, confirmation matters. That’s where lab testing comes in.

The first tool most clinicians turn to is serologic testing — looking for antibodies in the blood. If the immune system has recognized the measles virus, it produces a specific kind of antibody called IgM. These usually show up within a few days after the rash begins and help confirm a recent infection. IgG antibodies, which indicate longer-term immunity, can also be checked to confirm prior exposure or vaccination.

But there’s a timing issue: test too early, and the antibodies might not be detectable yet. That’s why follow-up testing is sometimes necessary.

For faster and more definitive answers, PCR testing is often used — especially during outbreaks. PCR looks directly for measles RNA in nasal or throat swabs, and it can detect infection even before the immune system has fully responded. It’s precise, fast, and especially useful in confirming early or atypical cases.

Ruling Out the Lookalikes

Even with all that information, measles isn’t diagnosed in a vacuum. Several other illnesses can produce a high fever and a rash, including rubella, scarlet fever, roseola, and even some drug reactions. That means clinicians need to think broadly at first — and then narrow the focus.

Rubella, for example, can look similar, but it tends to be milder and doesn’t usually come with a nasty cough or Koplik spots. Scarlet fever, caused by strep bacteria, often has a rough, sandpaper-like rash and a sore throat. Roseola causes a rash after the fever goes away, not during. Knowing these subtle distinctions helps steer the diagnosis in the right direction.

Still, if measles is suspected — especially in an unvaccinated patient during a time of active outbreak — doctors don’t wait for perfect certainty. Speed matters, because the sooner a case is identified, the sooner public health teams can act.

Why Speed and Certainty Matter

Measles doesn’t just affect the person who’s sick. It affects everyone around them. A single undiagnosed case can lead to dozens of new infections within days — especially in places like schools, airports, or clinics.

That’s why healthcare providers are urged to report suspected measles cases immediately, even before lab results return. It’s also why infected patients are often isolated right away — not out of panic, but out of necessity.

Quick diagnosis doesn’t just help the individual. It helps protect the wider community — especially infants, pregnant women, and people with weakened immune systems who can’t be vaccinated themselves.

Rapid PCR testing can catch the virus early — but diagnosis isn’t just about technology. It’s about pattern recognition, access, and timely clinical judgment.

We explored similar diagnostic strategies in our feature “CBC and Cancer Detection” — not about measles, but about how subtle lab clues can reveal serious disease long before it looks obvious.

So How Do You Know It’s Measles?

The answer is rarely just one symptom or one test. It’s the whole picture — a pattern of symptoms, a history of exposure, and the context in which it all occurs. It’s part art, part science, and part instinct built from asking good questions.

Because when you see measles, you can’t afford to look away.

Not just for the sake of one patient — but for the many others who don’t know they’re next.

Treatment: If There’s No Cure for Measles, What Can We Actually Do?

Here’s something a lot of people don’t realize:

There’s no antiviral drug for measles. Nothing you can take to directly kill the virus or make it disappear faster.

So what happens after someone is diagnosed? What does treatment actually look like — especially when the disease is serious, and the stakes are high?

The answer starts with a shift in mindset. With measles, treatment isn’t about attacking the virus itself — it’s about supporting the body while it fights back, and preventing complications before they get out of hand.

Let’s unpack what that actually means in practice.

Supportive Care: Holding the Line

Most measles patients — especially those who are otherwise healthy and well-nourished — can recover at home. But even in these “mild” cases, the virus still packs a punch. High fevers, relentless coughing, sore eyes, and fatigue can make it feel like the worst illness they’ve ever had.

So what does supportive care involve?

Hydration is key — fevers and diarrhea can lead to dehydration quickly, especially in kids. Rest is non-negotiable. Managing fever with medications like acetaminophen or ibuprofen helps with comfort, but aspirin is avoided, particularly in children, because of the risk of Reye’s syndrome.

In some cases, the cough can be severe enough to disturb sleep or interfere with breathing, so humidified air or honey (for kids over one year) can help. But remember: this isn’t about curing measles. It’s about giving the immune system the space to win.

Watching for Complications: Because It Can Turn Quickly

Even with basic care in place, measles can take a dangerous turn — sometimes with very little warning.

That’s why one of the most important roles of healthcare providers is to monitor for signs of worsening. Pneumonia is the most common cause of death in measles, especially in children under five and people with weakened immune systems. If someone with measles develops chest pain, difficulty breathing, or a sudden increase in fever, it’s a signal to escalate care immediately.

Then there’s encephalitis — rare, but catastrophic. If a patient becomes confused, drowsy, has seizures, or complains of severe headaches, the possibility of brain inflammation becomes very real. This is a medical emergency, and it’s one of the reasons measles needs to be taken so seriously, even after the rash fades.

And don’t forget: measles suppresses the immune system, sometimes for months. This increases the risk of secondary infections — things the body might otherwise be able to fight off. That’s why close follow-up is critical, even after the acute illness passes.

The Vitamin A Factor: More Than Just a Supplement

Now here’s a twist that surprises many people:

Vitamin A can actually save lives in measles.

In populations where vitamin A deficiency is common — particularly in parts of Africa and Southeast Asia — measles outcomes are significantly worse. The World Health Organization recommends high-dose vitamin A supplementationfor all children with measles in these settings. It’s been shown to reduce the risk of blindness, pneumonia, and even death.

Even in countries where deficiency is rare, doctors may give vitamin A to hospitalized children or those with severe disease — just in case.

This isn’t just a nutritional bonus. It’s a therapeutic tool that works because vitamin A plays a crucial role in immune function and in maintaining the integrity of epithelial tissues — like the lining of the lungs and the gut, which measles tends to attack.

Hospital Care: When the Home Isn’t Enough

When does a measles patient need to be hospitalized?

It usually comes down to complications, vulnerability, or instability. If a child is malnourished, dehydrated, or has underlying conditions like HIV, their risk of developing life-threatening problems goes way up. Hospitals offer access to oxygen therapy, IV fluids, antibiotics (for secondary infections), and neurologic monitoring — all things that can make the difference between survival and tragedy.

Unfortunately, in many low-resource areas, hospital care isn’t available or accessible — and that’s where measles becomes especially deadly. In these regions, measles can devastate entire communities not because the virus is stronger, but because the safety net is thinner.

What About Antivirals? Are There Any?

This is a common question, especially in a world used to quick fixes. Antivirals exist for diseases like flu, HIV, and even COVID-19 — so why not measles?

The truth is, measles moves too quickly and replicates in a way that makes it hard to target. By the time someone shows symptoms, the virus has already spread through their tissues, and the immune system has already begun its counterattack. At that point, there’s no specific drug that can help more than the body already is.

There are some experimental antivirals being studied, but for now, none are approved for clinical use. Which brings us back to the frustrating — and sobering — reality: we have to rely on prevention and supportive care, because once the virus gets in, we’re mostly reacting.

So What Can We Actually Do?

We support the body. We treat the complications. We use vitamin A when appropriate. We hospitalize the most vulnerable. And above all, we work to prevent the next case — because once someone has measles, the options are limited, and the risks are high.

That’s why doctors, nurses, and public health workers don’t just care about treating measles — they care about stopping it from happening in the first place.

Because here’s the hard truth:

If someone is sick with measles, they’re already past the point where we could have truly protected them.

Prevention: If We Know How to Stop Measles, Why Aren’t We Doing It?

Let’s be clear right from the start:

We already know how to prevent measles. We’ve known for decades. This isn’t a mystery. It’s not some complex puzzle we’re still trying to solve. We have the vaccine. It works. And yet — here we are.

So the obvious question is:

If measles is so preventable, why is it coming back?

To answer that, we have to look not just at the science, but at the systems and beliefs that shape real-world behavior — and the gaps that allow this virus to slip through.

The MMR Vaccine: What It Does, and Why It Works

The cornerstone of measles prevention is the MMR vaccine, which protects against measles, mumps, and rubella. It’s been around since the 1960s, and it’s one of the most rigorously tested, safest, and most effective vaccines ever developed.

The numbers are remarkable: one dose provides about 93% protection against measles; a second dose bumps that up to around 97%. That’s nearly bulletproof. And the immunity is long-lasting — often for life.

So why two doses? Because while one dose protects most people, a small percentage don’t build a strong enough immune response the first time. The second dose catches them — and that’s what makes population-level protection so powerful.

It’s not just about individual immunity. It’s about what we call herd immunity — the idea that if enough people in a community are vaccinated, the virus has nowhere to go. It can’t find new hosts. It fizzles out.

But herd immunity for measles requires a very high vaccination rate — about 95% coverage. That’s because measles is so contagious that even a small dip in immunity can open the door to an outbreak.

Why Do Vaccination Rates Drop?

This is where things get complicated. If the vaccine works, and if it’s widely available in many countries, then why are we seeing vaccination rates decline in certain places?

The answers vary by region — but here are some of the recurring themes:

In some countries, especially in areas affected by war, poverty, or displacement, vaccines are simply hard to access. Health clinics might be understaffed or too far away. Refrigeration systems might be unreliable. Families might not even know when or where to bring their children. These are infrastructure problems, and they can’t be solved just by having the vaccine in stock.

In other places — including some wealthier nations — the issue isn’t access. It’s trust. Misinformation about vaccine safety, especially on social media, has spread faster than any virus. False claims linking the MMR vaccine to autism (which have been thoroughly debunked) still circulate and shape parental decisions. Some people don’t trust government health agencies. Others simply don’t see measles as a threat anymore — they think of it as a “mild childhood illness,” not a disease that can blind, disable, or kill.

And here’s the paradox: the success of vaccination has made people forget why we needed it in the first place.

Strategies to Boost Coverage: What Can Actually Make a Difference?

Rebuilding measles protection isn’t just about shouting “Vaccinate!” louder. It takes nuance, local context, and real engagement.

In low-income countries, this might mean expanding mobile clinics, offering catch-up campaigns, and improving cold-chain logistics. It means going to where people are, not expecting them to come to the system.

In wealthier countries, it means rebuilding trust. That might involve training doctors to have empathetic conversations with hesitant parents — not confrontational ones. It might mean investing in science education, community partnerships, and transparency in how vaccine safety is monitored.

Some countries have implemented school-entry vaccine requirements, which can boost immunization rates significantly. Others have used mass immunization drives, particularly in outbreak settings. These are effective, but they require political will and community buy-in.

And everywhere, it means keeping measles on the public radar — even when the news cycle moves on. Because measles never moves on. It just waits for the gaps.

What Happens If We Don’t Reach Enough People?

The consequences are predictable — and avoidable. When vaccination coverage dips below the herd immunity threshold, outbreaks return. Sometimes slowly, sometimes explosively. And once they start, they can be hard to stop, especially in densely populated or under-immunized areas.

The cost isn’t just in lives lost, either. Measles outbreaks can overwhelm health systems, diverting resources away from other critical needs. Hospitals fill with preventable cases. Other routine care is delayed. It becomes a public health domino effect — and one that could have been avoided with a simple, safe injection.

So What’s the Real Answer?

The real answer is this: we prevent measles by valuing prevention itself. Not just on paper, not just in policy, but in practice — globally, consistently, and with urgency.

Because while we’ve made amazing progress over the past few decades, the virus doesn’t care about our track record. It only cares about the opportunity.

And when we let our guard down, it walks right through.

Recent Developments (2025–2026): Are We Learning Fast Enough — or Backsliding Further?

Here’s the thing about measles: it’s always watching for an opening. And in the past two years, it’s found more than a few.

So what’s been happening in 2025 and into 2026? What are the most significant trends, developments, and warning signs? Are we closing the immunity gap — or widening it?

Let’s take a closer look.

Outbreaks on the Rise: Are We Surprised?

Across multiple regions, measles cases have continued to climb, with several countries reporting their largest outbreaks in over a decade. In some areas, the virus has moved like wildfire through communities with alarmingly low vaccination rates.

In 2025 alone, outbreaks have been reported in:

- Eastern and Southern Africa, where political instability and health system disruptions have left millions of children without routine immunizations.

- South and Southeast Asia, where urban crowding and pandemic-era vaccine delays created fertile ground for transmission.

- Parts of Europe and North America, where vaccine hesitancy — not access — is the main barrier.

You might ask: Weren’t we expecting a post-pandemic bounce-back in vaccinations?

We were. And to some extent, it happened — especially in well-resourced nations with coordinated catch-up campaigns. But globally, we’ve only partially recovered. The World Health Organization estimated in early 2025 that nearly 20 million children worldwide had missed one or both doses of the MMR vaccine over the previous four years.

It’s a huge number — and it adds up to something dangerous: immunity debt. The longer it goes unaddressed, the bigger the outbreaks become.

A Shift in Public Health Response: Are We Getting Smarter?

In response to these outbreaks, some countries have ramped up public health campaigns in impressive ways.

India, for example, launched a large-scale “Immunization Resurgence” program in late 2024, combining house-to-house outreach with targeted social media education. By early 2026, preliminary data shows a significant bump in measles vaccine uptake — especially in hard-to-reach rural districts.

The UK and Germany, where vaccine hesitancy has been a mounting concern, have started funding local health influencers — including pediatricians and parent advocates — to counter disinformation in a more personalized, human way. The tone is shifting from lectures to conversations, and it seems to be resonating, especially with younger parents.

And in the U.S., some states have reinstated school-entry immunization requirements that had previously been relaxed or undermined by broad exemption policies. In areas where enforcement is strong, vaccination rates are climbing again.

But progress is uneven. Other regions are still struggling to find momentum, especially where trust in government remains low or where health infrastructure is still rebuilding post-COVID.

New Tools on the Horizon: Are We Innovating Fast Enough?

There’s growing interest in microneedle patches — a newer delivery method that could someday simplify measles vaccination. These patches don’t require syringes, refrigeration, or highly trained personnel. They could be game-changers for remote or resource-limited settings. Trials are ongoing, and results so far are promising — but global rollout is still a few years away.

Meanwhile, data surveillance tools are improving. Some countries are integrating AI-driven outbreak prediction models to help preempt the next wave — identifying regions at risk based on mobility data, social media trends, and immunization records. It’s not perfect, but it’s a sign that digital tools are being taken seriously in public health strategy.

But here’s the big question: Will these innovations reach the people who need them most?

Because fancy forecasting models and cutting-edge tech won’t do much if they can’t reach rural clinics, conflict zones, and communities that don’t trust the system.

Vaccine Recommendations: Are They Changing?

So far, the fundamental guidance — two doses of MMR, starting at 12–15 months and again at 4–6 years — hasn’t changed. But public health bodies are considering temporary dose schedule adjustments during outbreaks.

Some countries have recommended giving the first dose earlier — as early as 6 months — in high-risk settings. This doesn’t replace the regular schedule, but it offers earlier protection in places where the virus is actively circulating. The WHO and CDC are watching these changes closely, and further updates may come as more data accumulates.

There’s also renewed discussion about adult booster doses, particularly for healthcare workers and travelers heading into outbreak zones. In most cases, two documented doses are still considered fully protective. But where records are missing — or where immunity is in doubt — public health officials are erring on the side of caution.

These aren’t silver bullets — they’re glimpses of what’s possible when innovation and urgency align.

Additionally, don’t miss our coverage of “Avian Influenza H5N9”, which echoes many of these themes — emerging threats, preparedness gaps, and the tightrope between scientific advancement and real-world application.

Where Does This Leave Us?

We’re in a fragile moment. Some countries are pushing forward — rebuilding vaccine coverage, improving access, restoring public trust. Others are still catching their breath after years of disruption. And measles? Measles is just doing what it’s always done: waiting for us to miss a step.

So here’s the final question:

Are we responding to measles as the global threat it is — or just reacting to it as a local inconvenience?

Because measles doesn’t care where borders lie. And if we don’t treat this resurgence with the urgency and unity it demands, we’re going to keep having this conversation — over and over again.

FAQ: Measles — What People Are Still Asking

1. Isn’t measles just a harmless childhood illness?

Not at all. Measles can lead to serious complications like pneumonia, encephalitis, blindness, and death — especially in young children and people with weakened immune systems. It’s far from harmless, and its effects can linger long after the rash disappears.

2. How contagious is measles really?

Extremely. Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known to science. If one person has it, up to 90% of nearby unvaccinated people will catch it too. It spreads through the air and can linger in a room for up to two hours after the infected person has left.

3. I had the MMR vaccine as a child — am I still protected?

Most likely, yes. Two doses of the MMR vaccine offer about 97% lifetime protection against measles. If you’re unsure whether you received both doses, you can check your immunization records or get a blood test to check for immunity.

4. Can adults get measles?

Yes — especially if they were never vaccinated or only received one dose. Adults born before 1957 are usually considered immune due to natural exposure, but anyone uncertain about their vaccine status should speak with a healthcare provider.

5. What should I do if I think I’ve been exposed to measles?

If you’re vaccinated, your risk of infection is very low. If you’re unvaccinated or unsure, contact your doctor right away. Post-exposure prophylaxis — either with the MMR vaccine or immune globulin — may reduce your chances of getting sick if given early enough.

6. Why is measles coming back if we already had it under control?

Multiple reasons: vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, gaps in healthcare access, and pandemic-related disruptions have all played a role. When vaccination rates drop — even a little — measles finds a way back in.

7. Is there a treatment for measles?

There’s no antiviral cure. Treatment focuses on supportive care: fluids, rest, fever management, and monitoring for complications. In some cases, vitamin A is given to reduce severity, especially in children or those who are malnourished.

8. Can the measles vaccine cause autism?

No. This myth began with a discredited study that has been thoroughly debunked and retracted. Decades of research have shown no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. The vaccine is safe, effective, and saves lives.

9. What’s being done globally to fight measles now?

Efforts include catch-up immunization campaigns, improved vaccine delivery systems, real-time outbreak tracking, and community-based education to combat hesitancy. New technologies like microneedle patches may make vaccination easier in the future — but the key right now is increasing vaccine coverage.

Conclusion: What Now?

So here we are. After all this — the science, the outbreaks, the complications, the solutions — we’re left with one unavoidable truth: measles should not be a 21st-century problem. And yet, it is.

We have a safe, reliable vaccine. We understand how the virus works. We know how to stop it in its tracks. But science isn’t enough on its own. The resurgence of measles isn’t just a medical failure — it’s a social one.

Because what’s driving this comeback isn’t some new mutation or biological trick. It’s distrust. It’s disconnection. It’s what happens when access is unequal, when public health loses public confidence, and when we forget what vaccines were created to protect us from in the first place.

This isn’t just about protecting one child. It’s about protecting the infant too young to be vaccinated. The immunocompromised cancer patient. The overwhelmed health clinic trying to keep up. Measles reminds us that health is shared — and so is risk.

So what now?

We stop waiting for another outbreak to wake us up. We stop treating vaccination like a personal choice with only personal consequences. We invest — not just in vaccines, but in systems that deliver them, in people who explain them, and in communities that trust them.

And maybe, just maybe, we finally start listening to what measles has been trying to tell us all along:

You don’t stop me one person at a time.

You stop me together.