Bloating after meals: diagnosis and when testing is needed

Post-meal bloating: definitions, context, and when to worry

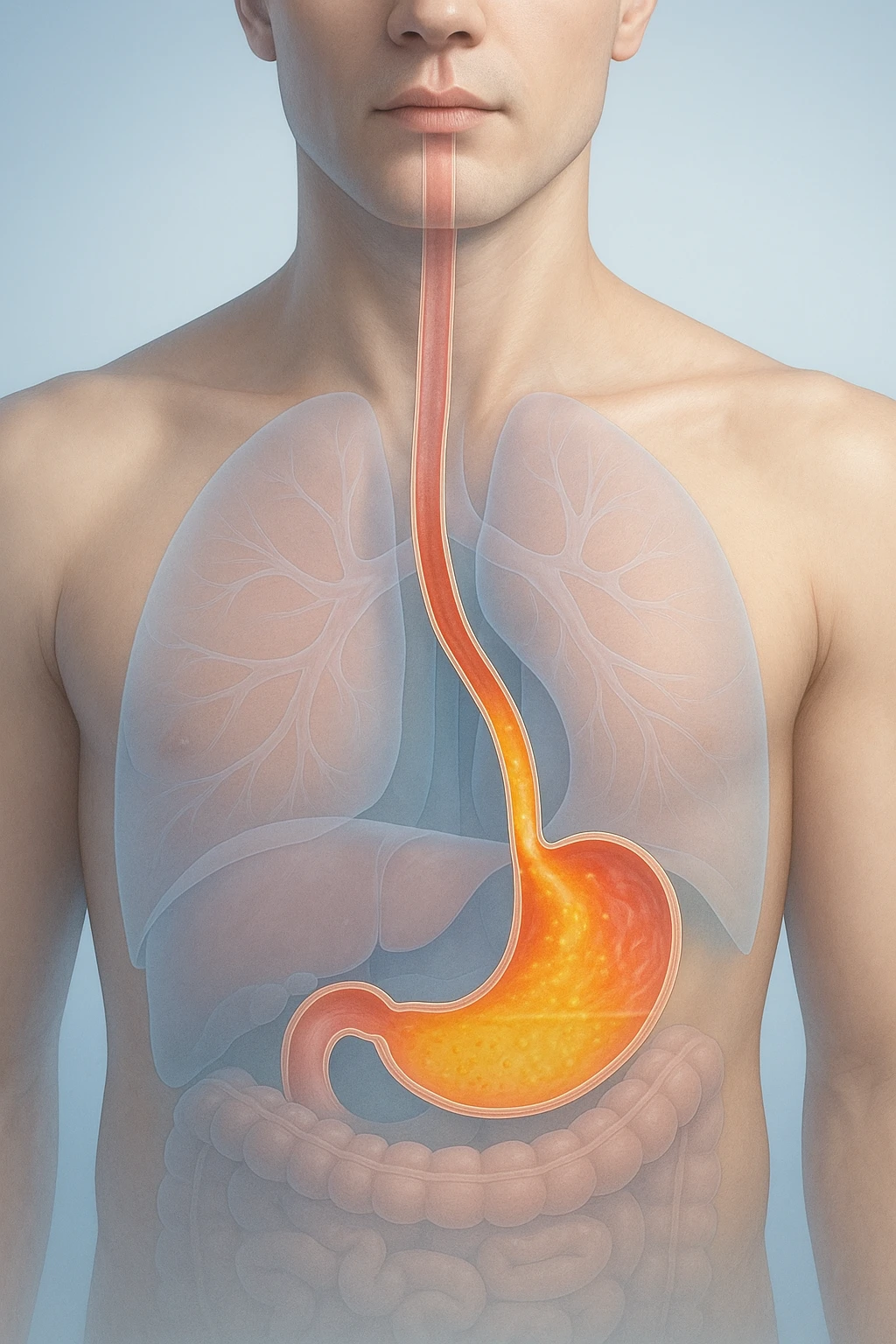

After eating, many people notice a sense of fullness or pressure in the abdomen. In clinical terms, bloating is this subjective sensation, whereas distension is an objective increase in abdominal size that can be observed or measured. Understanding the difference helps set expectations for evaluation and tracking response to care. When no structural disease is found, ongoing post-meal symptoms are often classified as a functional disorder using standardized Rome IV criteria after organic causes have been excluded. Day-to-day triggers frequently include carbonated beverages, rapid eating, and sugar alcohols in foods or drinks. In the context of bloating after meals, these distinctions clarify definitions and safety signals so readers know when to seek medical attention and set up why these symptoms occur after eating.

- Carbonated beverages

- Rapid eating

- Sugar alcohols in foods or drinks

Functional diagnoses and IBS overlap

Many patients meet Rome IV criteria after structural disease is excluded.

Bloating vs. distension

Bloating describes how you feel-an internal sense of pressure, tightness, or fullness. Distension refers to a visible or measurable increase in abdominal girth. Because one is a symptom and the other a sign, they may not always appear together. Distinguishing them guides evaluation: noting whether symptoms are mainly sensory (bloating) or accompanied by outward expansion (distension) helps clinicians focus the assessment and monitor whether changes over time reflect real improvement.

| Term | What it means |

|---|---|

| Bloating | Bloating describes how you feel-an internal sense of pressure, tightness, or fullness. |

| Distension | Distension refers to a visible or measurable increase in abdominal girth. |

Functional diagnoses and Rome IV

When examinations and basic investigations do not reveal an organic disease, persistent bloating or distension can be diagnosed as a functional gastrointestinal disorder using Rome IV criteria. This framework requires that structural disease be excluded first. Labeling symptoms in this way does not minimize their impact; rather, it provides a consistent language for patient-clinician discussion and a basis for targeted, stepwise management in later sections.

Who needs urgent assessment

Most post-meal bloating is benign, but certain features warrant prompt medical review because they raise concern for underlying disease. Seek care urgently if any of the following are present:

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (for example, black or bloody stools).

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Persistent change in bowel habits.

- Severe or persistent abdominal pain.

Clear guidance about these warning signs is important for safety. If none are present, recognizing common triggers-such as carbonated drinks, rapid eating, or sugar alcohols-can help frame discussions with your clinician while an appropriate, focused evaluation proceeds. Next, we will explore the mechanisms that make bloating more likely after meals.

Why it happens after eating: mechanisms that drive symptoms

Fermentation and carbohydrate malabsorption

After a meal, the gastrointestinal tract receives a mixture of nutrients that are digested and absorbed to varying degrees. Poorly absorbed fermentable carbohydrates pass into the lower gut and are metabolized by resident microbes, producing gas and increasing luminal volume. This rise in intraluminal content following carbohydrate fermentation can contribute to postprandial pressure and a visible sense of fullness.

The effect is particularly noticeable when the meal contains a higher load of fermentable substrates or is eaten quickly, as this can increase the amount that reaches the distal gut in a short period. In this context, bloating after meals reflects the mechanical consequence of additional gas and fluid combined with the gut’s normal post-meal (postprandial) responses.

- Poorly absorbed fermentable carbohydrates pass into the lower gut and are metabolized by resident microbes, producing gas and increasing luminal volume.

- This rise in intraluminal content following carbohydrate fermentation can contribute to postprandial pressure and a visible sense of fullness.

Motility, transit, and constipation

Movement of contents through the stomach and intestines-known as motility and transit-shapes how a meal feels. When transit is altered, material can linger longer than usual, allowing more time for gas accumulation and stretching. Delayed movement through the colon amplifies the sense of pressure after eating.

Constipation and outlet dysfunction are important contributors because retained stool can reduce available space in the colon and impede normal passage of gas. In these circumstances, even a typical post-meal increase in intestinal content may be experienced as disproportionate fullness or tightness, and patients may report that meals predictably worsen symptoms until bowel function improves.

- When transit is altered, material can linger longer than usual, allowing more time for gas accumulation and stretching.

- Constipation and outlet dysfunction are important contributors because retained stool can reduce available space in the colon and impede normal passage of gas.

Sensitivity and somatic responses

Bloating intensity is not determined by volume alone. Visceral hypersensitivity-heightened sensory signaling from the gut-can make normal postprandial changes feel excessive. In people with increased sensitivity, small shifts in pressure or stretch are perceived as marked discomfort or fullness, even when objective distension is modest.

Somatic responses of the abdominal wall also influence how symptoms appear. In abdominophrenic dyssynergia, the pattern of muscle activity during and after meals becomes maladaptive: abdominal wall muscles may relax outward while the diaphragm descends, promoting outward protrusion. This does not imply structural damage but represents a coordination issue that can magnify visible distension and the sensation of bloating. Together with gut microbiota perturbations and altered transit, these sensitivity and muscle-pattern changes explain why the same meal can feel very different from one person to another.

- Visceral hypersensitivity-heightened sensory signaling from the gut-can make normal postprandial changes feel excessive.

- In abdominophrenic dyssynergia, the pattern of muscle activity during and after meals becomes maladaptive: abdominal wall muscles may relax outward while the diaphragm descends, promoting outward protrusion.

Focused assessment: history first, selective tests second

Targeted history and exam

Evaluation starts with a careful history focused on how symptoms relate to meals, which foods or eating patterns precede them, and how bowel habits have changed. Clarifying whether the sensation is mainly bloating or accompanied by visible distension helps set an objective baseline for follow-up. A brief review of prior gastrointestinal diagnoses, medications, and recent travel provides additional context without defaulting to broad testing. On examination, clinicians document vital signs, abdominal tenderness or fullness, and visible girth changes when present; these observations guide whether further testing is necessary.

- How symptoms relate to meals and which foods or eating patterns precede them.

- Bowel habits and whether symptoms are accompanied by visible distension.

- Prior gastrointestinal diagnoses, medications, and recent travel.

- On exam: vital signs, abdominal tenderness or fullness, and visible girth changes when present.

This history-first approach reflects a key principle: routine extensive testing is low yield when there are no alarm features. Instead of ordering large panels up front, the assessment prioritizes the pattern of symptoms, their timing to meals, and objective findings to shape the next steps.

| Approach | Use |

|---|---|

| Routine extensive testing | Low yield when there are no alarm features. |

| Selective, question-driven tests | Chosen to answer specific questions; the result should reasonably change management. |

Which tests help most

When initial assessment suggests a possible underlying driver, selective tests are chosen to answer specific questions. Celiac serology is a common first-line test when symptoms and history raise suspicion, because it screens for a condition that can present with postprandial bloating. Breath testing can be considered in selected patients: hydrogen or methane breath tests may help evaluate carbohydrate malabsorption or suspected small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, but they are not appropriate as blanket screening.

- Celiac serology as a common first-line test when symptoms and history raise suspicion.

- Hydrogen or methane breath tests in selected patients to evaluate carbohydrate malabsorption or suspected small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

- Not appropriate as blanket screening.

Hydrogen/methane breath testing has methodological limitations that influence interpretation, including variability in test performance and the potential for false positive or negative results. For this reason, breath testing is best reserved for scenarios where clinical suspicion is meaningful and the result would reasonably change management. A targeted strategy avoids unnecessary downstream procedures that add cost and complexity without improving outcomes.

- Variability in test performance and the potential for false positive or negative results.

- Best reserved for scenarios where clinical suspicion is meaningful and the result would reasonably change management.

When to image or scope

Imaging and endoscopy are not routine parts of the initial workup for post-meal bloating in the absence of concerning findings. Their role is to investigate specific problems suggested by the history or exam, or to clarify abnormalities that emerge during selective testing. This staged approach aligns with the principle that exhaustive testing has low diagnostic yield when red flags are absent.

- Not routine without concerning findings.

- Investigate specific problems suggested by the history or exam.

- Clarify abnormalities that emerge during selective testing.

By sequencing evaluation-history and exam first, followed by selective, question-driven tests-clinicians can distinguish functional symptoms from conditions that need targeted investigation. This minimizes over-testing, reduces uncertainty, and keeps the focus on information that directly informs next steps in care.

Stepwise management: diet first, bowel function, then mind-gut and medicines

- Diet-first strategies

- Normalize bowel function and the pelvic floor

- Layer behavioral and pharmacologic options

Diet-first strategies

A practical plan begins with nutrition because what and how we eat often shapes post-meal symptoms. A structured, time-limited approach led by a dietitian helps identify personal triggers while maintaining nutritional adequacy. Many people improve with either a low-FODMAP trial or targeted restriction of specific items such as lactose and sugar alcohols, followed by systematic reintroduction to confirm tolerance. This method focuses on clarifying which fermentable carbohydrates most affect an individual rather than eliminating broad food groups indefinitely.

Because meals are a recurring exposure, aligning food choices with symptom patterns can produce meaningful reductions in postprandial pressure and visible distension. The goal at this stage is to learn which foods and portion sizes are better tolerated, then translate those findings into everyday habits that are realistic to sustain.

- A structured, time-limited approach led by a dietitian helps identify personal triggers while maintaining nutritional adequacy.

- Many people improve with either a low-FODMAP trial or targeted restriction of specific items such as lactose and sugar alcohols, followed by systematic reintroduction to confirm tolerance.

- This method focuses on clarifying which fermentable carbohydrates most affect an individual rather than eliminating broad food groups indefinitely.

- The goal at this stage is to learn which foods and portion sizes are better tolerated, then translate those findings into everyday habits that are realistic to sustain.

Normalize bowel function and the pelvic floor

Constipation and outlet dysfunction can cause or exacerbate bloating, so the next step is to restore regular, comfortable bowel movements. When stool retention reduces available colonic space, gas movement is restricted and post-meal fullness can feel disproportionate. Addressing bowel habits therefore complements dietary measures and may be essential for symptom control.

If features suggest pelvic floor involvement-for example, straining, a sense of incomplete evacuation, or difficulty expelling stool-assessment for dyssynergic defecation is appropriate. Pelvic floor biofeedback is recommended when dyssynergia is identified, as targeted retraining can improve coordination. In parallel, diaphragmatic breathing and other biofeedback techniques may help when abdominophrenic dyssynergia is suspected, aiming to reduce outward abdominal wall relaxation and perceived distension after meals.

- Constipation and outlet dysfunction can cause or exacerbate bloating.

- When stool retention reduces available colonic space, gas movement is restricted and post-meal fullness can feel disproportionate.

- Pelvic floor biofeedback is recommended when dyssynergia is identified, as targeted retraining can improve coordination.

- Diaphragmatic breathing and other biofeedback techniques may help when abdominophrenic dyssynergia is suspected, aiming to reduce outward abdominal wall relaxation and perceived distension after meals.

Layer behavioral and pharmacologic options

When symptoms persist despite diet and bowel optimization, mind-gut and medication strategies are added according to symptom pattern and comorbidities. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy can reduce bloating in disorders of gut-brain interaction, particularly when visceral hypersensitivity and symptom-related distress are prominent. These approaches address how the nervous system interprets normal postprandial changes, often improving both symptom intensity and day-to-day function.

Medication choices are individualized. Antispasmodics may help cramping phenotypes; peppermint oil offers antispasmodic effects for some; and neuromodulators can be considered when pain and hypersensitivity dominate. Because guidance on probiotics is inconsistent-and at least one guideline advises against their use for bloating or distension-routine probiotic use is not emphasized in this stepwise plan. Throughout, shared decision-making anchors the sequence: adjust one element at a time, monitor response, and advance only when benefits are uncertain or insufficient, keeping the overall strategy focused and efficient.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy can reduce bloating in disorders of gut-brain interaction.

- Antispasmodics may help cramping phenotypes; peppermint oil offers antispasmodic effects for some; and neuromodulators can be considered when pain and hypersensitivity dominate.

- Because guidance on probiotics is inconsistent-and at least one guideline advises against their use for bloating or distension-routine probiotic use is not emphasized in this stepwise plan.

- Adjust one element at a time, monitor response, and advance only when benefits are uncertain or insufficient.

FAQ: Bloating after meals

Why does bloating after meals happen on some days but not others?

Several mechanisms can combine after eating: fermentation of poorly absorbed carbohydrates, altered gut motility or transit, and heightened visceral sensitivity. These vary by meal composition and individual gut-brain responses.

Do carbonated drinks and sugar alcohols really worsen symptoms?

Yes. Carbonated beverages introduce gas, and sugar alcohols are poorly absorbed fermentable carbohydrates that can increase intestinal gas and luminal distension after meals.

Is small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) the usual cause?

No. Bloating after meals is multifactorial. Breath tests for suspected SIBO have methodological limitations and are best used selectively when results would change management.

When are medical tests recommended?

Routine extensive testing is low yield if there are no alarm features. Selective testing-such as celiac serology or targeted breath tests-may be appropriate based on clinical suspicion.

Which symptoms mean I should seek urgent care?

Warning signs include gastrointestinal bleeding, unexplained weight loss, a persistent change in bowel habits, and severe or persistent abdominal pain. These warrant prompt medical evaluation.

Can constipation cause bloating after meals?

Yes. Constipation and outlet dysfunction can restrict gas movement and reduce available colonic space, making post-meal fullness feel disproportionate.

Will a low-FODMAP or targeted diet help?

Dietitian-guided low-FODMAP or targeted restriction of triggers like lactose or sugar alcohols can reduce symptoms for many people. Reintroduction helps identify individual tolerance.

Are probiotics recommended for post-meal bloating?

Guidance differs, and at least one guideline advises against routine probiotic use for bloating or distension. They are not universally recommended.

What non-drug approaches are supported?

Cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy can reduce symptoms in gut-brain interaction disorders. Diaphragmatic breathing and biofeedback may help abdominophrenic dyssynergia.

Which medications might be considered if symptoms persist?

Options depend on symptom pattern and comorbidities. Antispasmodics, peppermint oil, and neuromodulators are potential choices discussed with a clinician.