Belching: causes, types, and when to seek care

Belching: What’s Normal and When to Worry

Belching is a familiar body function, and for most families it’s simply a sign that swallowed air is leaving the upper part of the digestive tract. In healthy children and adults, belching happens many times a day within a normal range and doesn’t mean anything is wrong. Understanding the two main patterns-gastric and supragastric-can help parents notice what’s typical for their child and what might deserve a closer look. Gastric belching reflects gas that vents from the stomach, while supragastric belching involves rapid air movement into and out of the esophagus without reaching the stomach. Knowing the difference sets the stage for appropriate next steps if belching becomes disruptive at home, at school, or during activities.

Plain-Language Definition

Belching is the oral expulsion of gas from the upper gastrointestinal tract. Put simply, it’s air that travels upward and is released through the mouth.

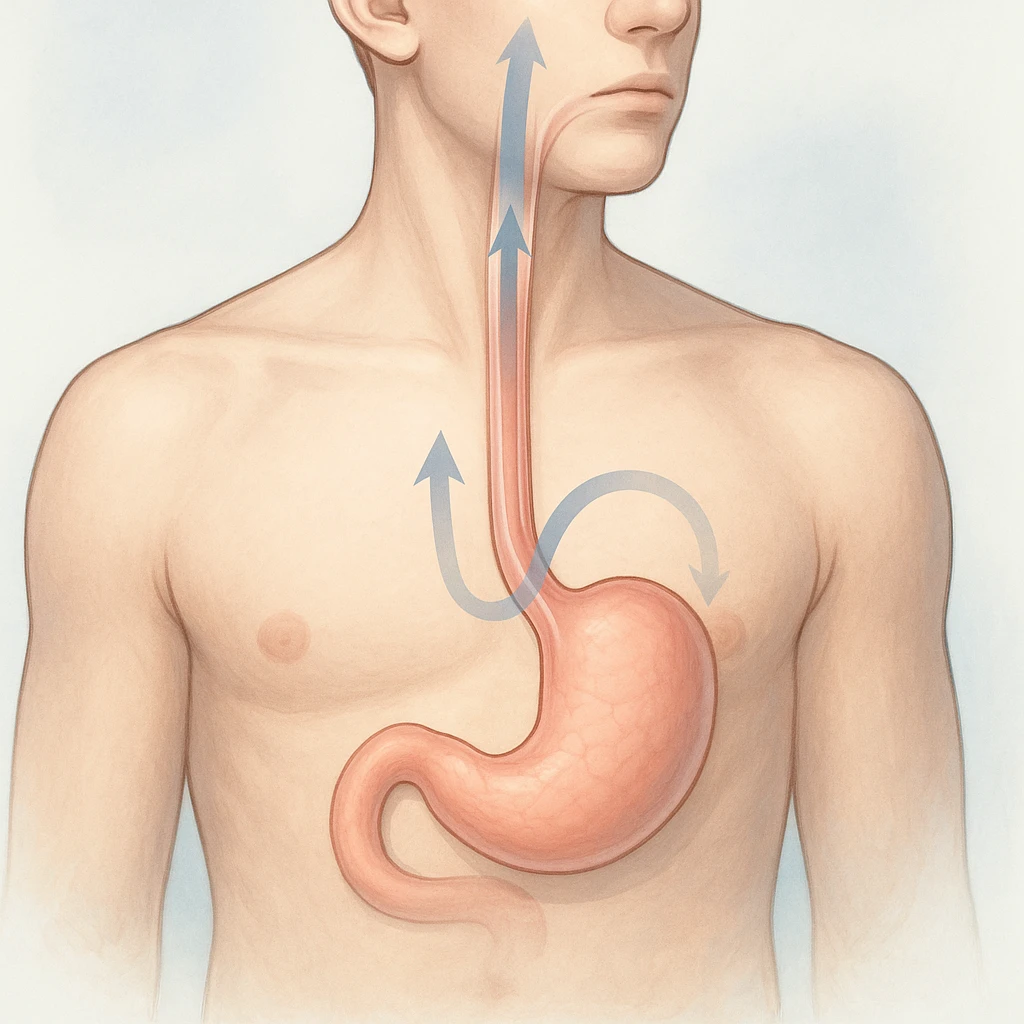

- In gastric belching, that air has accumulated in the stomach and is vented outward.

- In supragastric belching, air is quickly drawn into the esophagus and then expelled, so the movement starts and ends above the stomach.

This distinction matters because the pattern offers clues about where the air is and how the body is moving it. For families, recognizing that not all belching is the same can reduce worry and make conversations with a clinician clearer and more focused.

Belching Myths vs Facts

| Myth | Fact |

|---|---|

| Myth: All belching comes from “too much gas in the stomach.” | Fact: Belching can be gastric, but it can also be supragastric, in which air rapidly moves into and out of the esophagus without reaching the stomach. |

| Myth: Any daily belching is abnormal. | Fact: Belching happens in healthy people; many experience it multiple times per day within a normal range. Concern rises when belching is bothersome, frequent, and impairs activities, consistent with recognized diagnostic criteria. |

With these basics in place, the next section explores common triggers and conditions that can influence how often belching occurs.

Why Belching Happens: Triggers, Conditions, and Subtypes

Belching can increase for simple, everyday reasons or as part of a digestive pattern linked to other conditions. Families often notice that episodes cluster around meals, busy conversations, or moments of nervous energy. Understanding common triggers and how the digestive tract moves air helps explain why belching shows up at certain times and why patterns differ from one person to another.

Everyday Triggers

Several day-to-day habits can increase swallowed air, a contributor to belching. Aerophagia-literally swallowing air-can happen during rapid eating, frequent talking while chewing, or sipping fizzy, carbonated beverages that release gas. Even equipment like poorly fitting dentures can let extra air in during meals, adding to the amount that later needs to be released.

- Families may also observe that belching is more noticeable after specific situations: a quick lunch between activities, a carbonated drink at sports practice, or animated conversations at the dinner table.

- In many people, symptoms are most apparent around meals, during anxiety, or when talking a great deal, reflecting how air intake and timing influence when gas reaches the upper digestive tract.

Linked Digestive Conditions

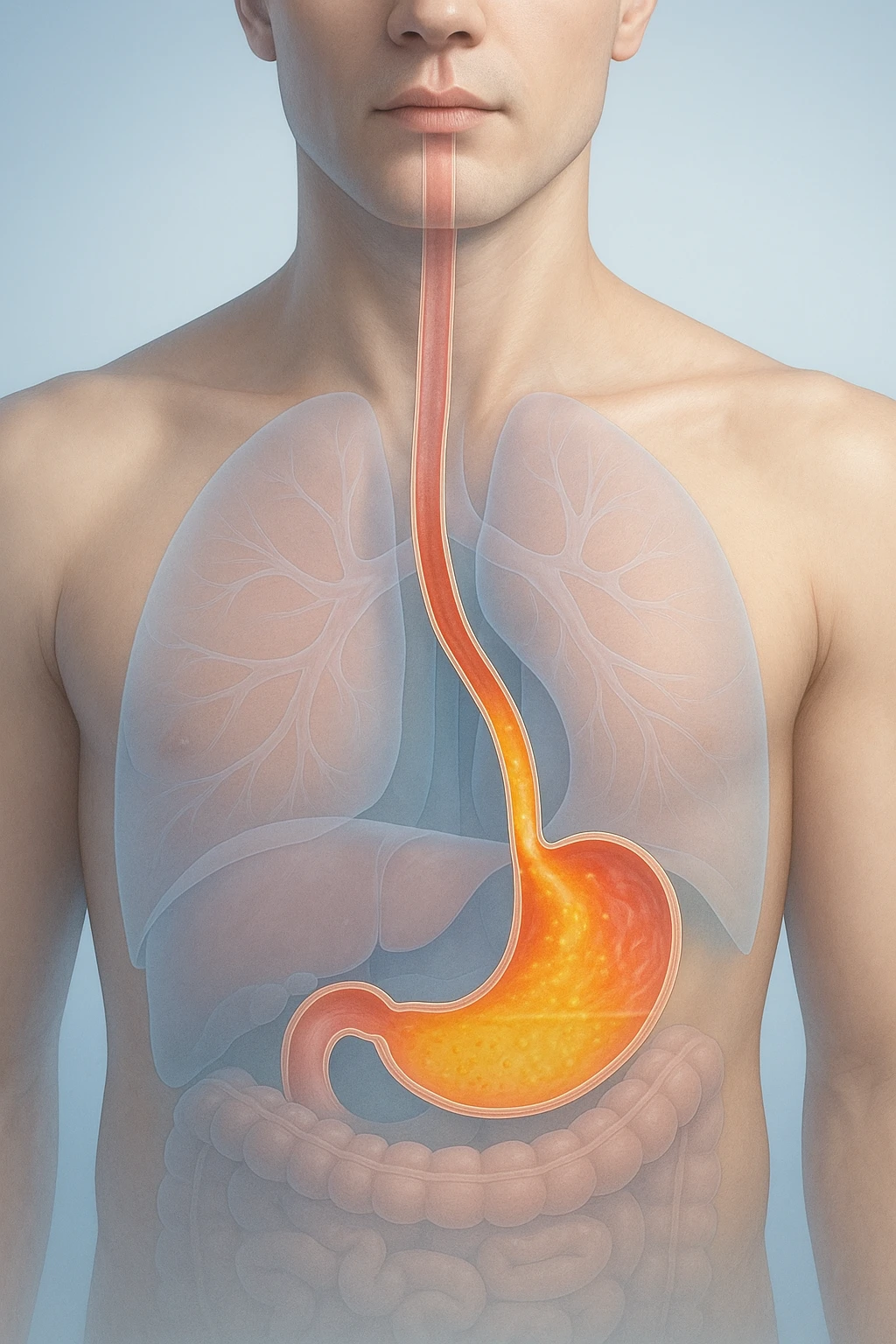

Belching can occur on its own, but it also appears alongside other gastrointestinal conditions. Functional GI disorders can coexist with belching, shaping how symptoms are felt and reported. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may be present in some individuals, and certain carbohydrate malabsorption patterns can add gas that needs to be released.

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and gastroparesis are additional conditions that may accompany belching in some cases.

- When these are present, the overall digestive environment changes-how food moves and how gas is produced-so belching may become more frequent or more noticeable in daily routines.

Gastric vs Supragastric

Belching does not always come from the same place. In gastric belching, gas that has accumulated in the stomach vents upward through the esophagus and out of the mouth. This is a familiar pathway and often follows eating or drinking.

Supragastric belching follows a different route: air rapidly flows into the esophagus from the mouth and then exits before reaching the stomach. This quick in-and-out movement creates a distinct pattern that feels repetitive and can appear during conversation or moments of tension. Recognizing whether belching is gastric or supragastric clarifies what is happening inside the body and helps families make sense of when and why episodes occur.

| Subtype | Description |

|---|---|

| Gastric belching | In gastric belching, gas that has accumulated in the stomach vents upward through the esophagus and out of the mouth. |

| Supragastric belching | Supragastric belching follows a different route: air rapidly flows into the esophagus from the mouth and then exits before reaching the stomach. |

Belching: Targeted Treatments, Co-existing Conditions, and Outlook

Behavioral Therapy First

For supragastric belching, first-line therapy centers on behavioral interventions. Approaches such as diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and speech therapy target the rapid air inflow and outflow pattern in the esophagus and align treatment with the underlying mechanism. When these strategies are paired with attention to personal triggers, symptoms often improve, reflecting the value of matching care to the belching subtype and everyday contexts in which episodes occur.

- Because day-to-day patterns can influence how frequently belching appears, targeted behavioral work provides a practical framework for families.

- By focusing on techniques that reduce the behaviors driving supragastric belching and by reinforcing consistent trigger management, this approach supports durable improvement while keeping the plan straightforward and understandable.

OTC and Pharmacologic Aids

Over-the-counter options may be used selectively, guided by what is contributing to symptoms. Alpha-galactosidase may help when gas is related to specific carbohydrates, and lactase helps when lactose intolerance is present. These enzyme-based aids are most relevant when a clear dietary link is identified and can be incorporated as part of a broader plan centered on behavioral and trigger-focused strategies.

- Evidence for commonly used gas remedies such as simethicone and activated charcoal is limited, so their use is optional and based on individual response.

- Framing them as adjuncts rather than stand-alone solutions keeps expectations realistic and maintains focus on the strategies most closely linked to the mechanism of belching.

Follow-Up and Prognosis

With targeted behavioral therapy and consistent trigger management, many people experience symptom improvement. Recurrence can occur without ongoing strategies, so follow-up emphasizes maintaining the techniques that helped and revisiting triggers if patterns shift over time. When symptoms remain persistent or disabling, when the diagnosis is uncertain, or when specialized behavioral therapy is needed, referral to gastroenterology is appropriate to guide next steps.

- This stepwise outlook balances practical home strategies with clear thresholds for specialty input.

- It also provides a path for families to understand progress over time, recognize when additional support is warranted, and stay focused on approaches that align treatment with the type of belching and the daily triggers that influence it.

Belching FAQs

Is frequent belching always a sign of too much stomach acid?

No. Belching can come from stomach gas (gastric) or rapid air movement in and out of the esophagus (supragastric). The pattern, not acid level, often explains symptoms.

Which everyday habits can increase belching?

Rapid eating, frequent talking while chewing, using straws, chewing gum, and drinking carbonated beverages increase swallowed air. Poorly fitting dentures can also let extra air in during meals.

Could another digestive condition be contributing?

Yes. Belching may accompany functional gastrointestinal disorders, GERD, carbohydrate malabsorption, SIBO, or gastroparesis. Addressing co-existing issues can influence symptom patterns.

When does belching become a medical disorder?

When it is frequent, bothersome, and interferes with daily activities. Diagnostic frameworks also consider symptom persistence for at least three months with onset six months earlier.

What situations commonly trigger episodes?

Meals, anxiety, and extended talking are common contexts for belching. Families often notice clustering around busy conversations or hurried eating.

How do clinicians evaluate belching at the first visit?

They start with history, diet review, and a physical examination. Testing is reserved for alarm features or atypical findings.

What are the red flags that need prompt care?

Unintended weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, progressive dysphagia, persistent vomiting, fever, or an abnormal examination warrant timely evaluation.

What diagnostic test can confirm the belching subtype?

Esophageal impedance-pH monitoring can distinguish supragastric from gastric belching when results would change management.

Do over-the-counter products help belching?

Alpha-galactosidase may help when gas relates to specific carbohydrates, and lactase helps with lactose intolerance. Evidence for simethicone and activated charcoal is limited.

What treatments work best for supragastric belching?

Behavioral therapy is first-line, including diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and speech therapy. Many people improve with targeted techniques and trigger management.

Belching: Targeted Treatments, Co-existing Conditions, and Outlook

Behavioral Therapy First

For supragastric belching, first-line therapy centers on behavioral interventions. Approaches such as diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and speech therapy target the rapid air inflow and outflow pattern in the esophagus and align treatment with the underlying mechanism. When these strategies are paired with attention to personal triggers, symptoms often improve, reflecting the value of matching care to the belching subtype and everyday contexts in which episodes occur.

- Because day-to-day patterns can influence how frequently belching appears, targeted behavioral work provides a practical framework for families.

- By focusing on techniques that reduce the behaviors driving supragastric belching and by reinforcing consistent trigger management, this approach supports durable improvement while keeping the plan straightforward and understandable.

OTC and Pharmacologic Aids

Over-the-counter options may be used selectively, guided by what is contributing to symptoms. Alpha-galactosidase may help when gas is related to specific carbohydrates, and lactase helps when lactose intolerance is present. These enzyme-based aids are most relevant when a clear dietary link is identified and can be incorporated as part of a broader plan centered on behavioral and trigger-focused strategies.

- Evidence for commonly used gas remedies such as simethicone and activated charcoal is limited, so their use is optional and based on individual response.

- Framing them as adjuncts rather than stand-alone solutions keeps expectations realistic and maintains focus on the strategies most closely linked to the mechanism of belching.

Follow-Up and Prognosis

With targeted behavioral therapy and consistent trigger management, many people experience symptom improvement. Recurrence can occur without ongoing strategies, so follow-up emphasizes maintaining the techniques that helped and revisiting triggers if patterns shift over time. When symptoms remain persistent or disabling, when the diagnosis is uncertain, or when specialized behavioral therapy is needed, referral to gastroenterology is appropriate to guide next steps.

- This stepwise outlook balances practical home strategies with clear thresholds for specialty input.

- It also provides a path for families to understand progress over time, recognize when additional support is warranted, and stay focused on approaches that align treatment with the type of belching and the daily triggers that influence it.

Belching FAQs

Is frequent belching always a sign of too much stomach acid?

No. Belching can come from stomach gas (gastric) or rapid air movement in and out of the esophagus (supragastric). The pattern, not acid level, often explains symptoms.

Which everyday habits can increase belching?

Rapid eating, frequent talking while chewing, using straws, chewing gum, and drinking carbonated beverages increase swallowed air. Poorly fitting dentures can also let extra air in during meals.

Could another digestive condition be contributing?

Yes. Belching may accompany functional gastrointestinal disorders, GERD, carbohydrate malabsorption, SIBO, or gastroparesis. Addressing co-existing issues can influence symptom patterns.

When does belching become a medical disorder?

When it is frequent, bothersome, and interferes with daily activities. Diagnostic frameworks also consider symptom persistence for at least three months with onset six months earlier.

What situations commonly trigger episodes?

Meals, anxiety, and extended talking are common contexts for belching. Families often notice clustering around busy conversations or hurried eating.

How do clinicians evaluate belching at the first visit?

They start with history, diet review, and a physical examination. Testing is reserved for alarm features or atypical findings.

What are the red flags that need prompt care?

Unintended weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, progressive dysphagia, persistent vomiting, fever, or an abnormal examination warrant timely evaluation.

What diagnostic test can confirm the belching subtype?

Esophageal impedance-pH monitoring can distinguish supragastric from gastric belching when results would change management.

Do over-the-counter products help belching?

Alpha-galactosidase may help when gas relates to specific carbohydrates, and lactase helps with lactose intolerance. Evidence for simethicone and activated charcoal is limited.

What treatments work best for supragastric belching?

Behavioral therapy is first-line, including diaphragmatic breathing, cognitive-behavioral strategies, and speech therapy. Many people improve with targeted techniques and trigger management.