Frozen Shoulder Treatment and Long-Term Outlook

Frozen Shoulder: Clinical Overview and Epidemiologic Context

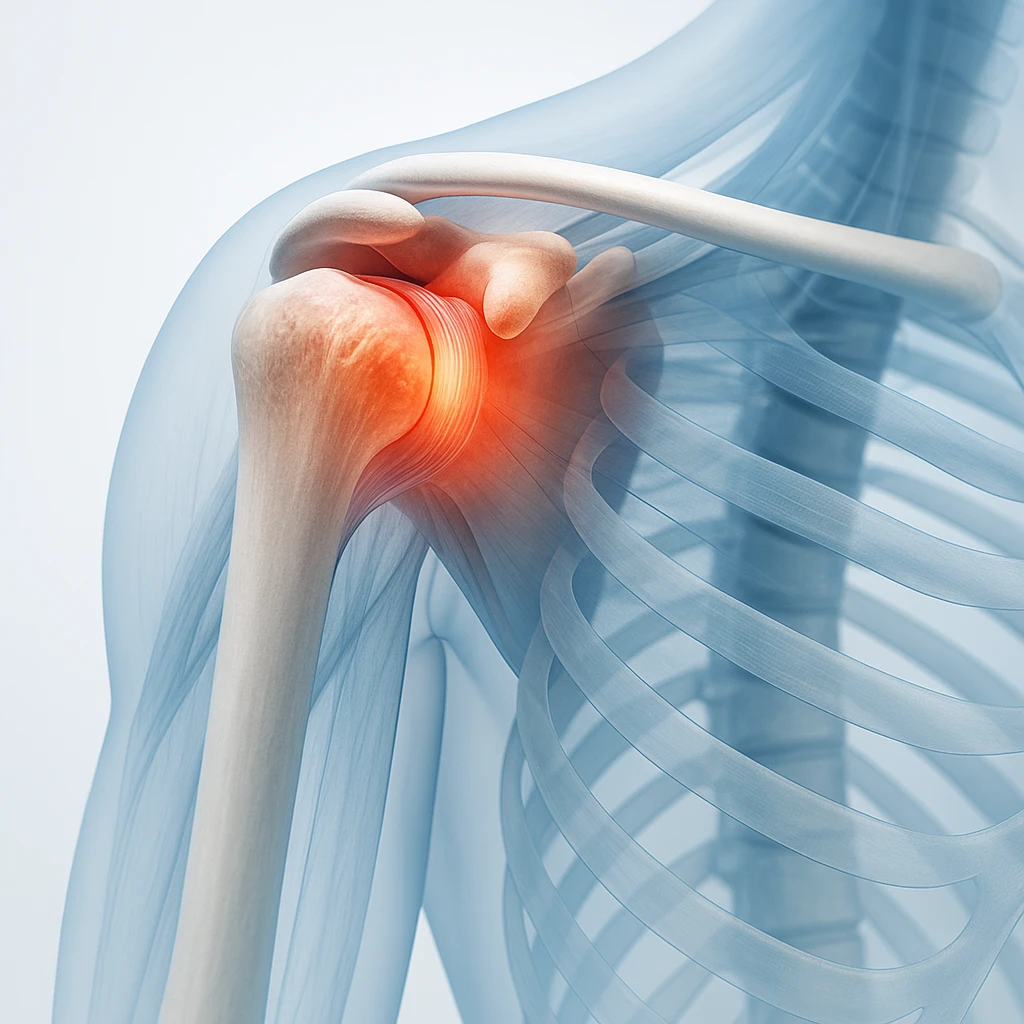

Frozen shoulder, medically known as adhesive capsulitis, is a progressive disorder of the glenohumeral joint characterized by pain and restricted movement. It develops gradually, beginning with subtle stiffness and discomfort before advancing to marked limitation of motion. Recognizing its presentation early is essential for timely intervention and prevention of chronic functional impairment.

Definition and Key Features

Adhesive capsulitis is defined by a progressive loss of both active and passive range of motion in the shoulder joint without structural abnormalities. Even with external assistance, the shoulder cannot achieve full movement. Hallmark symptoms include:

- Shoulder stiffness and diffuse pain, often worse at night

- Difficulty performing overhead or behind-the-back movements

- Loss of both active and passive motion, especially external rotation

The condition primarily affects the glenohumeral capsule, which becomes thickened and contracted, reducing joint mobility. Diagnosis is clinical, supported by a characteristic history and examination showing global restriction of motion.

Epidemiologic Context and Clinical Burden

Frozen shoulder affects about 2-5% of the general population and is a common musculoskeletal condition in clinical practice. It typically occurs between ages 40 and 60, with a female predominance. While it may arise spontaneously, it is frequently linked to metabolic or endocrine disorders such as diabetes mellitus, which predispose to prolonged or severe disease.

The condition can significantly impair quality of life by:

- Limiting upper limb function and daily activities

- Disrupting sleep due to persistent pain

- Interfering with occupational and recreational performance

Awareness of these epidemiologic patterns aids early recognition and management to prevent chronic stiffness and disability.

Risk Factors and Pathophysiologic Mechanisms of Frozen Shoulder

Frozen shoulder develops through complex systemic, metabolic, and local factors that disrupt the normal balance of inflammation and repair in the shoulder capsule, leading to stiffness and pain.

Systemic and Metabolic Risk Factors

Endocrine and metabolic disorders are major contributors to frozen shoulder. Common associations include:

- Diabetes mellitus: markedly increases risk and is linked to a more severe and prolonged disease course.

- Thyroid disease: especially hypothyroidism, which can alter connective tissue turnover and inflammatory response.

- Metabolic disturbances: chronic hyperglycemia promotes fibrosis by thickening and stiffening collagen fibers in the capsule.

These systemic disorders modify the shoulder’s microenvironment, predisposing it to inflammation and fibrosis.

Local and Mechanical Contributors

Mechanical and local factors can initiate or worsen frozen shoulder. Common contributors include:

- Prior shoulder injury or surgical procedures

- Prolonged immobilization following trauma or illness

- Dupuytren’s disease, a fibroproliferative condition of the hand, which may share similar fibrotic mechanisms

When shoulder motion is restricted for extended periods, capsular tissues may contract and adhere, limiting glenohumeral mobility.

Topic Details

The disease process progresses from active inflammation to chronic fibrosis. Initially, the synovial lining of the capsule becomes inflamed, causing pain and restricted motion. Over time, excessive collagen deposition thickens and stiffens the capsule, producing contracture and persistent immobility. This inflammatory-fibrotic cascade may be influenced by metabolic and autoimmune factors, linking systemic disease with localized dysfunction.

Clinical Stages and Diagnostic Evaluation of Frozen Shoulder

Frozen shoulder follows a predictable clinical course and is primarily diagnosed through history and examination. Understanding its stages and clinical findings supports accurate diagnosis, while imaging helps exclude alternative causes of shoulder stiffness.

Triphasic Clinical Course

Adhesive capsulitis evolves through three overlapping stages:

- Freezing stage: gradual onset of diffuse pain, worse at night, with increasing stiffness.

- Frozen stage: pain plateaus while stiffness dominates, restricting daily activities.

- Thawing stage: gradual restoration of motion as pain diminishes and capsule elasticity returns.

The full course may span months to years, with individual variability in duration and recovery.

Physical Examination and Diagnostic Features

Diagnosis is clinical and relies on characteristic findings, including:

- Global restriction of both active and passive range of motion, especially external rotation

- Pain at end-range movements

- Compensatory scapular motion during arm elevation

These features help distinguish frozen shoulder from other shoulder conditions that typically preserve passive motion, allowing diagnosis without extensive imaging.

Role of Imaging and Differential Diagnosis

Imaging supports exclusion of other causes of shoulder pain and stiffness:

| Imaging Modality | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Plain radiographs | Rule out osteoarthritis or calcific tendinopathy. |

| Ultrasound / MRI | Evaluate for rotator cuff tear or soft-tissue pathology; may show mild capsular thickening in frozen shoulder. |

Common differential diagnoses include glenohumeral arthritis, rotator cuff tear, and subacromial bursitis, each with distinct clinical patterns.

When to Seek Medical Evaluation: Persistent stiffness and night pain lasting more than 4-6 weeks despite rest or modification of activity should prompt medical review for possible frozen shoulder.

Conservative Treatment and Rehabilitation for Frozen Shoulder

Most cases of frozen shoulder respond to nonoperative treatment aimed at reducing pain, restoring movement, and preventing recurrence. Management typically progresses from pain control to structured physiotherapy. Patient education and adherence are critical for successful outcomes.

Pain Management and Anti-inflammatory Therapy

During the early pain-dominant phase, therapy focuses on inflammation control to enable movement. Common approaches include:

- Analgesics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to relieve pain and improve tolerance to motion

- Education on posture, activity modification, and gentle use of the arm to reduce stiffness

- Encouraging shoulder mobility within pain-free limits to prevent secondary restriction

These measures help maintain joint function by reducing inflammation in the capsule and surrounding tissues.

Physiotherapy and Exercise-Based Rehabilitation

Physiotherapy is essential for regaining range of motion (ROM) and functional strength. Core principles include:

- Supervised stretching and ROM exercises to restore capsule flexibility

- Tailored therapy based on stage-passive techniques in painful phases and active strengthening as pain improves

- Consistent home exercise programs to sustain progress between sessions

Regular, controlled movement within pain-free limits promotes gradual recovery and prevents recurrence.

Adjunctive Interventions

When conservative measures plateau, adjunctive treatments may provide short-term benefit:

- Intra-articular corticosteroid injections: reduce pain and improve function, particularly in early stages, and work best alongside physiotherapy.

- Capsular distension (hydrodilatation): fluid-assisted capsule stretching that can offer temporary relief; guideline endorsement remains variable.

These interventions are reserved for patients with limited improvement despite standard care.

Interventional Options and Long-Term Outcomes in Frozen Shoulder

While most patients with frozen shoulder recover through conservative therapy, a subset experience persistent stiffness and pain despite prolonged nonoperative management. In these refractory cases, procedural intervention may be necessary to restore functional mobility and alleviate discomfort. Understanding the indications, potential risks, and expected outcomes of such procedures supports appropriate escalation of care in a safe, structured manner.

Procedural Management for Resistant Cases

When conservative therapy fails to achieve adequate improvement, the following interventional procedures may be considered:

- Manipulation under anesthesia (MUA): controlled mobilization of the shoulder joint while the patient is under anesthesia to break adhesions within the capsule and improve range of motion. Although effective, it carries potential risks such as humeral fracture or rotator cuff injury and is reserved for patients unresponsive to less invasive care.

- Arthroscopic capsular release: a minimally invasive surgical procedure that releases contracted portions of the joint capsule under direct visualization. It is indicated for severe, persistent stiffness that limits daily function despite extensive rehabilitation and is followed by structured postoperative physiotherapy to maintain motion gains.

Recovery Expectations and Prognosis

Frozen shoulder generally follows a prolonged but self-limiting course, with most patients achieving gradual improvement over one to three years. Even after intervention, full recovery of motion may take several months. Important prognostic considerations include:

- Typical timeline: functional recovery commonly occurs within one to three years.

- Prognostic modifiers: diabetes mellitus is associated with slower recovery and a higher likelihood of residual stiffness.

- Outcome expectation: most individuals regain satisfactory shoulder function, though mild residual limitation may persist in some cases.

Prevention and Long-Term Care

Long-term management focuses on maintaining shoulder mobility and preventing recurrence of stiffness, particularly following injury or surgery requiring immobilization. Effective preventive strategies include:

- Initiating early, gentle movement and guided rehabilitation after immobilization.

- Adhering to prescribed exercise programs to maintain joint flexibility and function.

- Continuing routine shoulder mobility exercises after recovery to reduce recurrence risk, especially in predisposed individuals.

Frequently Asked Questions About Frozen Shoulder

- Is frozen shoulder the same as arthritis?

- No. Frozen shoulder involves thickening and tightening of the joint capsule, while arthritis affects the joint surfaces and causes bone or cartilage changes.

- How long does frozen shoulder usually last?

- The condition often follows a gradual course lasting one to three years. Recovery times vary, but most people regain useful movement over time.

- Can frozen shoulder develop after surgery or injury?

- Yes. Prolonged shoulder immobilization after injury or surgery can trigger stiffness and capsule tightening, especially if early movement is delayed.

- Who is most likely to get frozen shoulder?

- It most often affects adults aged 40 to 60, particularly women and those with diabetes or thyroid disease.

- What are the early warning signs to watch for?

- Gradual shoulder pain, especially at night, and mild stiffness that slowly worsens are common early signs before significant motion loss develops.

- Can frozen shoulder heal on its own?

- Yes. Many cases resolve gradually without surgery, though full recovery may take months or years, depending on severity and underlying conditions.

- How is frozen shoulder diagnosed?

- Doctors rely on clinical examination showing limited active and passive motion in all directions and use imaging only to rule out other problems.

- Does diabetes affect recovery from frozen shoulder?

- Yes. People with diabetes tend to have slower recovery and may retain more residual stiffness even after treatment.

- What treatments help reduce pain and stiffness?

- Physical therapy, gentle stretching, and sometimes corticosteroid injections help relieve pain and restore mobility. Surgery is considered only for resistant cases.

- Can frozen shoulder come back after it heals?

- Recurrence in the same shoulder is uncommon, but individuals with diabetes or prolonged immobilization may develop it in the opposite shoulder later.