Persistent Hiccups in Diaphragmatic Tumors

Persistent Hiccups in Diaphragmatic Tumors: When a Common Symptom Signals Something Serious

- Why Do Hiccups Occur in Diaphragmatic Tumors?

- Understanding the Mechanism: From Tumor to Hiccup

- How Often Does This Happen in Patients with Diaphragmatic or Thoracic Tumors?

- What Causes These Hiccups in the Context of Cancer?

- When to Worry: Signs That Hiccups May Signal Trouble

- Diagnostic Approaches in Persistent Hiccups

- How Oncologists Treat and Manage Hiccup Symptoms

- Can This Condition Be Prevented or Minimized?

- Do These Hiccups Go Away with Treatment?

- What Specialists Say About Persistent Hiccups

- Questions to Ask Your Oncology Team

- FAQ: Persistent Hiccups in Diaphragmatic Tumors

Why Do Hiccups Occur in Diaphragmatic Tumors?

Most people experience hiccups as harmless and temporary. But in rare cases—especially in cancer patients—they can become chronic and debilitating. Persistent hiccups, defined as those lasting more than 48 hours, may be a sign of irritation or pressure on the diaphragm, phrenic nerves, or central nervous system.

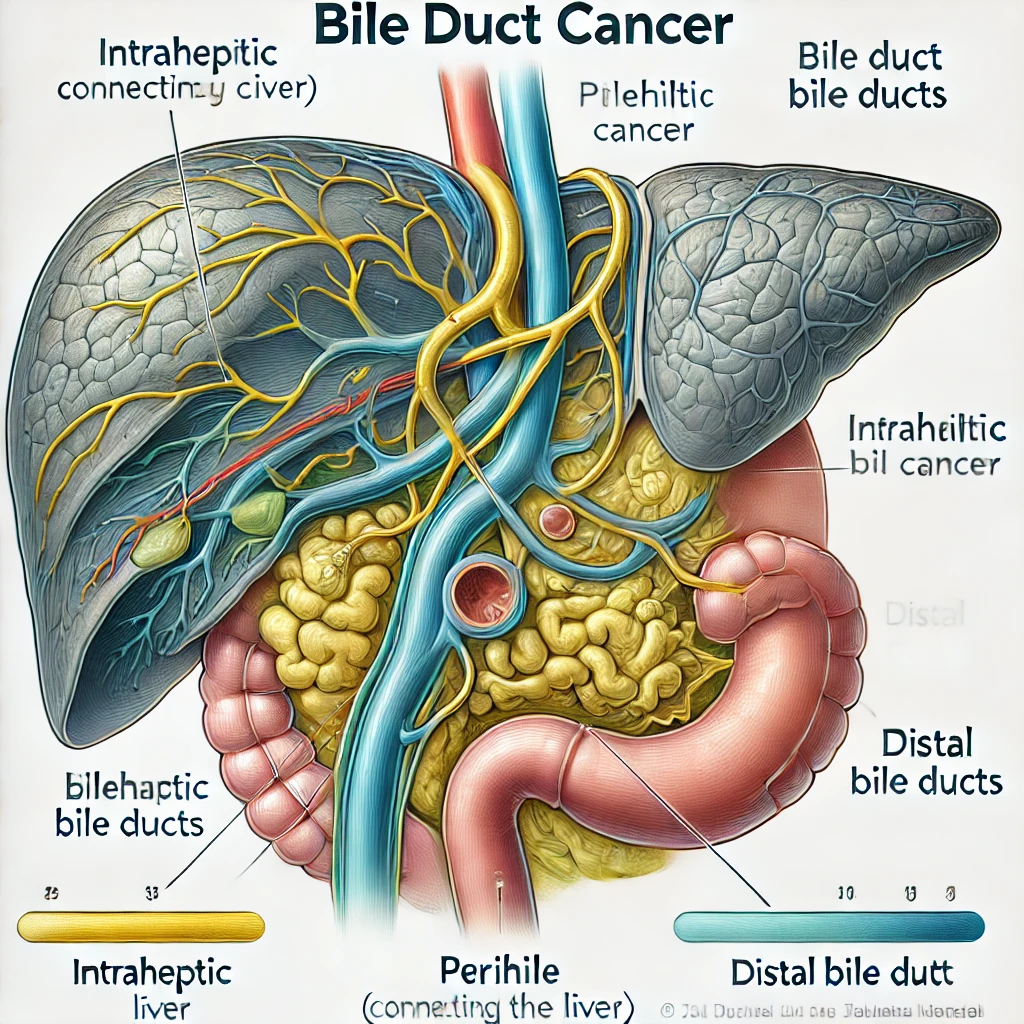

In patients with tumors in the region of the diaphragm or mediastinum, hiccups are more than just an inconvenience. They can reflect tumor infiltration, compression, or even metastasis to the peritoneum or thoracic cavity. The diaphragm is a thin muscle critical for breathing, and when affected by a mass, its function and neural control can be disrupted.

Hiccups may start subtly but become severe enough to interfere with eating, sleeping, and medication compliance. In some cases, they are resistant to typical remedies and require oncologic intervention.

Understanding the Mechanism: From Tumor to Hiccup

The pathophysiology behind hiccups in cancer patients often involves direct or indirect disruption of the hiccup reflex arc. This arc includes the phrenic nerve, vagus nerve, and parts of the brainstem. Diaphragmatic tumors can press on or infiltrate these nerves or adjacent tissues, triggering involuntary diaphragmatic contractions.

Additional causes include local inflammation, pleural effusion, or abdominal distension from tumor growth. Chemotherapy and corticosteroids may also increase the sensitivity of the hiccup reflex through electrolyte shifts or central stimulation.

Physiological Links Between Tumors and Hiccups

| Affected Structure | Possible Tumor Impact Leading to Hiccups |

| Diaphragm | Mechanical irritation or inflammation |

| Phrenic nerve | Compression or tumor infiltration |

| Vagus nerve | Chemical or physical stimulation |

| Brainstem | Lesions from metastasis or medication |

| Peritoneum | Metastasis to the peritoneum causing gastric or diaphragmatic pressure |

This reflex is highly sensitive to pressure changes. Even small tumors or metastases near the diaphragm can provoke ongoing spasms.

How Often Does This Happen in Patients with Diaphragmatic or Thoracic Tumors?

Persistent hiccups are not among the most commonly reported cancer symptoms, but they are seen with surprising frequency in specific cases—particularly where thoracic or upper abdominal tumors are involved. According to clinical reviews, 5–15% of patients with mediastinal masses or upper GI malignancies report recurrent hiccups at some point.

They are more common in men, especially in those with hepatic or esophageal involvement, likely due to anatomical differences in diaphragmatic innervation. In diaphragmatic or lower lung tumors, hiccups may be an early, indirect sign of encroachment on the phrenic nerve or nearby structures.

Frequency Based on Tumor Location

| Tumor Location | Reported Incidence of Persistent Hiccups |

| Diaphragm or lower thorax | High (15–20%) |

| Upper GI tract (esophagus/stomach) | Moderate (10–12%) |

| Brainstem or CNS tumors | Moderate (5–10%) |

| Distant cancers without peritoneal/thoracic spread | Rare (<3%) |

Documentation remains limited due to underreporting, especially in palliative settings where hiccups are seen as minor despite their distressing impact.

What Causes These Hiccups in the Context of Cancer?

The causes of persistent hiccups in cancer patients are multifactorial and include both mechanical and chemical triggers. Tumors may directly affect structures or nerves involved in the hiccup reflex. In other cases, treatments, medications, or metabolic imbalances related to cancer progression play a role.

Primary and Secondary Causes of Hiccups in Cancer

| Type | Example Causes |

| Anatomical | Tumor in diaphragm, tumor markers indicating nerve involvement, metastatic spread |

| Pharmacological | Steroids (e.g., dexamethasone), chemotherapy (cisplatin, carboplatin) |

| Metabolic | Low sodium (hyponatremia), uremia, hypercalcemia |

| Inflammatory/Neurologic | CNS lesions, vagal irritation, phrenic nerve inflammation |

| Gastrointestinal | Distended stomach, ascites, metastasis to the peritoneum |

Persistent hiccups can also be a signal of serious electrolyte disturbance, which may not be evident until late-stage disease or during intensive treatment regimens.

When to Worry: Signs That Hiccups May Signal Trouble

While occasional hiccups are usually harmless, persistent or intractable hiccups in patients with known or suspected cancer warrant urgent attention. Hiccups that last longer than 48 hours—or that occur multiple times per day over several weeks—are considered pathological, especially when associated with weight loss, nausea, or thoracic discomfort.

In the context of tumors, hiccups can indicate disease progression, nerve involvement, or complications like pleural effusion or peritoneal metastasis. If they worsen with time, interrupt sleep, or coincide with neurologic symptoms (such as confusion or imbalance), they may reflect brain or brainstem involvement.

Red Flags in Cancer-Related Hiccups

| Symptom or Context | Clinical Concern |

| Hiccups lasting >48 hours | Persistent reflex arc activation |

| Associated chest or upper abdominal pain | Tumor expansion or inflammation |

| New hiccups in advanced-stage patients | Likely metastatic complication |

| Worsening hiccups on steroids or chemo | Drug-induced or metabolic |

| Hiccups with headache or confusion | Possible CNS involvement |

Persistent hiccups should not be ignored, especially in patients already being treated for cancer. They may provide a subtle but important clue to evolving disease burden, especially in the diaphragmatic, peritoneal, or neurologic compartments.

Diagnostic Approaches in Persistent Hiccups

Evaluating hiccups in cancer patients starts with a thorough clinical history and physical exam. The location of the tumor, the onset of hiccups, and any accompanying signs (e.g., cough, hoarseness, bloating) all help determine the source of irritation.

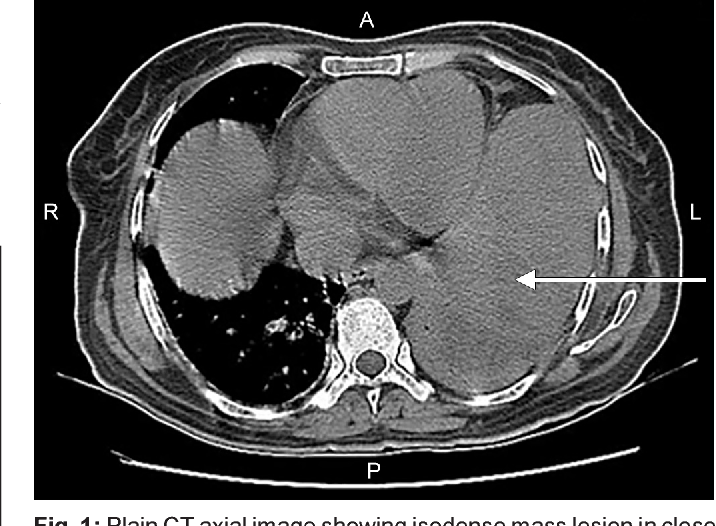

For patients with known diaphragmatic or thoracic malignancies, imaging is essential. CT scans or MRIs can detect nerve compression, new masses, or metastasis to the peritoneum. Bloodwork may reveal metabolic causes like electrolyte imbalances, while upper endoscopy helps identify GI tract issues.

Diagnostic Tools and Their Purpose

| Test or Imaging Modality | What It Evaluates |

| CT Chest/Abdomen | Tumor mass, pressure on diaphragm or nerves |

| MRI Brain/Brainstem | Central lesions, metastasis to hiccup centers |

| Bloodwork (electrolytes, renal, calcium) | Metabolic disturbances that trigger hiccups |

| Tumor Marker Panels | Tumor markers indicating progression or spread |

| Endoscopy (if GI symptoms present) | Esophageal or gastric mass, reflux, or inflammation |

These tools help determine if the hiccups are benign and transient—or if they are a manifestation of tumor behavior or systemic deterioration.

How Oncologists Treat and Manage Hiccup Symptoms

Treatment for hiccups in diaphragmatic tumors depends on the underlying cause. If hiccups result from direct nerve compression or tumor inflammation, addressing the cancer (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation) is the primary goal. Symptom control may also be needed in the short term.

Several medications have been found effective, including baclofen (a muscle relaxant), gabapentin, chlorpromazine, and metoclopramide. If hiccups are caused by steroid use, tapering the drug or substituting with an alternative is sometimes effective. For severe or refractory cases, phrenic nerve block or vagus nerve stimulation may be considered.

Symptom Management in Persistent Hiccups

| Strategy | Application |

| Medication-based therapy | Baclofen, gabapentin, metoclopramide, chlorpromazine |

| Cancer-directed treatment | Radiation, chemo, surgery to reduce tumor mass |

| Steroid adjustment | Reduce dose or switch corticosteroids |

| Nutritional/electrolyte support | Correct imbalances (Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+) |

| Interventional techniques | Nerve block, acupuncture, vagus nerve stimulation |

| Psychological support | Especially in palliative care settings |

Care plans are individualized, especially if hiccups are chronic and interfere with nutrition, sleep, or medication adherence.

Can This Condition Be Prevented or Minimized?

Complete prevention of hiccups in patients with diaphragmatic tumors is difficult, particularly if the tumor is aggressive or metastatic. However, there are effective strategies to reduce frequency and severity, especially in high-risk individuals.

Proactive treatment of metabolic imbalances, careful adjustment of corticosteroids, and early cancer detection improve outcomes. In post-surgical patients, minimizing phrenic nerve irritation during thoracic procedures helps reduce iatrogenic hiccups.

Preventive Measures for Cancer-Related Hiccups

| Preventive Focus | Preventive Action |

| Early detection of tumor growth | Regular imaging, tumor marker monitoring |

| Medication management | Monitor for hiccup-inducing drugs |

| Metabolic stability | Maintain sodium, calcium, magnesium levels |

| Patient education | Encourage early reporting of hiccup symptoms |

| Oncologic control | Shrink tumors before nerve involvement occurs |

Patients with metastasis to the peritoneum, large thoracic masses, or chemotherapy-induced side effects may benefit from anticipatory management using anti-hiccup medications as part of supportive care.

Do These Hiccups Go Away with Treatment?

Whether persistent hiccups in diaphragmatic tumors resolve with treatment depends largely on the cause and stage of the underlying malignancy. If hiccups result from tumor compression or irritation of the diaphragm or phrenic nerve, they often improve once the tumor responds to chemotherapy, radiation, or surgical debulking.

However, in advanced or metastatic cases—particularly when tumors have invaded multiple structures or caused permanent nerve damage—the symptom may persist despite cancer-directed therapy. Hiccups linked to metabolic changes or drug side effects usually resolve more quickly with supportive treatment or medication adjustments.

Prognosis of Hiccups Based on Underlying Cause

| Underlying Cause | Likelihood of Resolution |

| Tumor-induced nerve compression | Moderate to high (if responsive to treatment) |

| Chemotherapy or steroid-induced hiccups | High (with dose adjustment) |

| Brainstem metastasis | Low to moderate (depends on lesion size/control) |

| Postoperative phrenic irritation | High (often transient) |

| Metabolic imbalance | High (correctable) |

In some cases, hiccups resolve spontaneously once the acute cause—such as a flare in inflammation or a change in therapy—is addressed. But for others, particularly in terminal phases, symptom control becomes the main focus.

What Specialists Say About Persistent Hiccups

Oncologists and palliative care physicians agree that persistent hiccups, while often overlooked, can significantly diminish quality of life for patients with diaphragmatic tumors. They report that hiccups are especially burdensome when they interfere with sleep, eating, or cause distress in family settings.

Gastroenterologists often assist in ruling out gastrointestinal triggers, while neurologists may be consulted when hiccups are associated with CNS lesions. According to specialists, early intervention is key—not only to reduce discomfort, but to potentially catch signs of disease progression, such as metastasis to the peritoneum or phrenic nerve invasion.

Pain and symptom management teams emphasize a multimodal approach that combines drug therapy, psychological support, and where possible, targeted oncologic treatment. A recurrent theme across specialties is the need for better documentation and recognition of hiccups as a real clinical problem—not just a side note.

Questions to Ask Your Oncology Team

If you or your loved one is experiencing persistent hiccups in the context of cancer, here are important questions to discuss with your medical team:

| Question | Why It Matters |

| What is likely causing my hiccups? | Identifies whether it’s tumor, treatment, or metabolic |

| Could my tumor be pressing on a nerve or diaphragm? | Evaluates possible mechanical causes |

| Are these hiccups dangerous or just uncomfortable? | Assesses risk of underlying pathology |

| Should I undergo imaging to look for new growth? | Detects tumor progression or metastasis |

| Are any of my medications contributing to this? | Helps reduce or switch problematic drugs |

| Can you prescribe something to stop the hiccups? | Requests symptom management |

| Will this resolve with ongoing cancer treatment? | Sets expectations for recovery |

| Can these hiccups affect my ability to eat or sleep? | Evaluates impact on daily function |

| Should I worry about aspiration or choking? | Safety concern with prolonged episodes |

| Would adjusting my cancer treatment help? | Considers modifying oncologic plan |

| Is this a sign that my cancer has spread? | Monitors for tumor markers or metastasis |

| Do I need to see a neurologist or gastroenterologist? | Seeks interdisciplinary support |

| Is this symptom common in diaphragmatic tumors? | Normalizes experience or flags red flags |

| Are there non-drug methods to try? | Explores acupuncture, breathing therapy, etc. |

| What should I do if hiccups get worse suddenly? | Prepares for emergencies |

FAQ: Persistent Hiccups in Diaphragmatic Tumors

1. Are hiccups common in cancer patients?

They’re not among the most reported symptoms, but they do occur, particularly with thoracic or diaphragmatic tumors.

2. What makes hiccups last for days or weeks?

Chronic stimulation or compression of the phrenic or vagus nerve—often by a tumor—can cause hiccups that persist beyond 48 hours.

3. Should I be alarmed by persistent hiccups?

Yes, if they interfere with daily life or coincide with other symptoms. They could indicate tumor growth or complications.

4. Can medications cause hiccups?

Yes. Steroids, chemotherapy agents like cisplatin, and some antibiotics are known to trigger hiccups.

5. How do I know if the tumor is causing the hiccups?

Imaging (CT, MRI) and symptom correlation help doctors determine the cause.

6. Do hiccups ever mean cancer has spread?

Yes, especially if there’s metastasis to the peritoneum or CNS that affects the hiccup reflex arc.

7. Can hiccups be treated effectively?

In many cases, yes—with medications, tumor treatment, or nerve management techniques.

8. Will lifestyle changes help reduce hiccups?

Sometimes. Avoiding carbonated drinks, eating slowly, and managing stress may help milder cases.

9. Can hiccups affect nutrition?

Absolutely. Prolonged hiccups can lead to nausea, loss of appetite, and even vomiting.

10. Is hiccup surgery a real option?

Rarely, but nerve blocks or neurostimulation may be considered in extreme cases.

11. Are hiccups a late sign in cancer?

They can appear at any stage but are often more persistent in advanced disease.

12. Can I manage hiccups at home?

You can try gentle home remedies, but persistent symptoms require medical evaluation.

13. What if nothing helps?

Palliative teams can offer advanced symptom management focused on comfort.

14. Are there any labs to predict hiccup risk?

No direct test exists, but tumor markers and metabolic panels may suggest contributing factors.

15. Should I document my hiccup episodes?

Yes, especially if they are new or changing. It helps your doctor evaluate patterns and triggers.