Chronic Cough in Male Lung Cancer Patients

Chronic Cough in Male Lung Cancer Patients: A Symptom Worth Investigating

- Why Chronic Cough Is Common in Male Lung Cancer Patients

- The Mechanism: How Tumors and Treatment Trigger the Cough Reflex

- How Common Is Chronic Cough Among Men with Lung Cancer?

- Clinical Patterns: Stage and Site Dependence of the Cough Symptom

- Underlying Causes of Chronic Cough in Lung Cancer Patients

- When Chronic Cough Warrants Immediate Medical Evaluation

- Diagnostic Methods Used to Assess Chronic Cough in Male Lung Cancer Patients

- Treatment and Symptom Relief for Chronic Cough in Lung Cancer

- Can Chronic Cough in Lung Cancer Be Prevented?

- Does the Cough Eventually Go Away or Persist?

- What Oncologists Say About Managing Chronic Cough

- 15+ Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Chronic Cough and Lung Cancer

Why Chronic Cough Is Common in Male Lung Cancer Patients

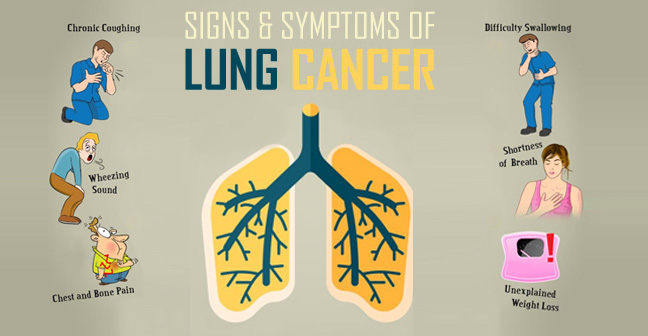

A persistent cough is one of the most frequently reported symptoms among men diagnosed with Lung Cancer. It may precede diagnosis or worsen with disease progression, and in many cases, it serves as the earliest warning sign. For some, this cough starts subtly—perhaps dismissed as seasonal bronchitis or smoker’s cough—until it becomes persistent, painful, or disruptive to sleep.

Coughing in these patients can be dry or productive, and may be accompanied by hoarseness, throat irritation, or chest discomfort. Unlike infectious coughs, which improve with time or antibiotics, this symptom lingers for weeks or months, reflecting ongoing airway irritation, tumor pressure, or pleural involvement.

Male patients, particularly long-term smokers, often delay seeking evaluation, believing the cough is harmless. This delay contributes to late-stage diagnoses and worse outcomes, especially when combined with coexisting respiratory conditions such as COPD or emphysema.

The Mechanism: How Tumors and Treatment Trigger the Cough Reflex

The mechanism of chronic cough in Lung Cancer patients is complex and multifactorial. It often begins when cancerous growths develop in or near the airways. These tumors can directly stimulate cough receptors located in the bronchial tree or trachea. Even microscopic lesions or pre-invasive cells can cause persistent irritation.

When tumors invade the mediastinum or compress the recurrent laryngeal nerve, vocal cord dysfunction and cough may follow. Tumors near the diaphragm or pleura may cause referred cough via phrenic nerve involvement.

Additionally, lung cancer treatment—including chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapy—can exacerbate the symptom. These treatments may inflame airways, damage surrounding tissues, or increase mucus production, all of which perpetuate the cough reflex. Some medications, including checkpoint inhibitors, may even cause immune-mediated pneumonitis, leading to dry, hacking coughs.

The chronic nature of the cough often stems from both direct tumor effects and the inflammatory environment they create, especially when complicated by lymphatic congestion or infection.

How Common Is Chronic Cough Among Men with Lung Cancer?

Chronic cough affects a majority of male lung cancer patients, especially those with central tumors or pre-existing lung disease. Studies estimate that up to 65–75% of newly diagnosed patients experience a cough that lasts for weeks or months. In late-stage diagnoses, this percentage rises even higher, often accompanied by shortness of breath, wheezing, or blood-tinged sputum.

The table below outlines prevalence patterns based on disease stage and location:

| Stage of Lung Cancer | Frequency of Chronic Cough | Additional Observations |

| Stage I (localized) | 30–40% | Often dry and mild |

| Stage II (nodal spread) | 50–60% | May begin producing sputum |

| Stage III (regional invasion) | 70–80% | Associated with hoarseness or wheezing |

| Stage IV (metastatic) | 80–90% | Often productive, may include hemoptysis |

Tumor location also matters. Central tumors near the trachea and bronchi tend to provoke cough more intensely than peripheral nodules. When the cancer has metastasized to the pleura or lymphatic system—as seen in Lung Cancer Metastasis—irritation of the respiratory lining amplifies the symptom even further.

Clinical Patterns: Stage and Site Dependence of the Cough Symptom

The nature of the cough changes depending on where the tumor is located and how advanced the disease has become. In early-stage cases (stage I), the cough is typically nonproductive and mild. Patients may describe it as dry, irritating, or “tickling.” Often it’s overlooked or mistaken for postnasal drip or acid reflux.

As the cancer spreads to nearby lymph nodes or tissues (stage II–III), the cough becomes more persistent and forceful. Patients may report coughing fits that disrupt sleep, social interactions, or eating. In these stages, voice changes or a sensation of chest fullness may also appear, especially if the recurrent laryngeal or phrenic nerves are involved.

In stage IV disease, cough often becomes productive. Blood-streaked sputum or frothy secretions may suggest airway invasion or pleural effusion. In some cases, metastases to other organs provoke systemic symptoms that worsen respiratory control.

Importantly, dermatological signs such as Lung Cancer Skin Rash may co-occur, indicating immune or paraneoplastic activity, which can also trigger chronic inflammation in the lungs.

Underlying Causes of Chronic Cough in Lung Cancer Patients

The chronic cough experienced by male lung cancer patients is driven by a combination of direct tumor effects, treatment-related complications, immune responses, and coexisting medical conditions. Understanding the range of causes is key to tailoring the right interventions.

Oncological factors include physical obstruction of the bronchial tubes by the tumor mass, pleural irritation, and airway invasion. Central tumors, especially those involving the mainstem bronchi or mediastinum, are notorious for triggering cough due to direct stimulation of cough receptors.

Medication-related causes are common. Chemotherapy agents such as taxanes and platinum-based drugs may cause inflammation of the mucosa. Targeted therapies and immunotherapies can trigger drug-induced pneumonitis, a serious complication that manifests with persistent dry cough.

Metabolic disturbances like electrolyte imbalance, anemia, and malnutrition can weaken respiratory muscle coordination or increase systemic inflammation, thereby prolonging cough episodes. In patients with cachexia or advanced-stage disease, reduced lung reserve further amplifies the coughing burden.

Infectious causes should also be considered. Immunosuppression due to cancer therapy makes patients vulnerable to pneumonia, fungal infections, and reactivation of latent viruses—each of which can provoke or worsen cough.

When Chronic Cough Warrants Immediate Medical Evaluation

While many lung cancer patients develop a chronic cough, there are situations where this symptom signals a complication requiring urgent evaluation. Recognizing red flags can be life-saving.

Coughing up blood (hemoptysis) is one of the most critical signs. Even a small amount of blood in sputum can indicate tumor erosion into blood vessels or coexisting bronchitis with fragile capillaries. In rare cases, massive hemoptysis may occur, posing an immediate risk of airway obstruction or hemorrhage.

Sudden worsening of cough, especially if accompanied by fever or chest pain, may suggest pneumonia or pleural effusion. Likewise, the appearance of wheezing, stridor, or hoarseness can indicate obstruction of the central airway or involvement of the vocal cords.

Patients reporting fatigue, weight loss, or shortness of breath alongside worsening cough should be screened for disease progression, including Lung Cancer Metastasis. If the cough becomes uncontrollable or disrupts daily life severely, hospitalization may be needed to prevent dehydration, rib fractures, or sleep deprivation.

Diagnostic Methods Used to Assess Chronic Cough in Male Lung Cancer Patients

Diagnosing the cause of a chronic cough in lung cancer involves a detailed clinical evaluation supported by imaging, laboratory tests, and endoscopic techniques.

Imaging is the first step. A chest X-ray can identify visible tumors, fluid buildup, or collapsed lung areas. CT scans provide more detailed views of tumor size, lymph node involvement, and airway narrowing. PET-CT may be used to detect metastasis or inflammation.

Bronchoscopy allows direct visualization of the airways. In male patients with a worsening cough and known central lung tumors, bronchoscopy is crucial for assessing mucosal involvement or obstruction. It also enables biopsy of suspicious areas.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) may be used to evaluate airflow limitation or restrictive lung patterns. These are particularly useful when trying to distinguish between cancer-related cough and other chronic lung conditions like COPD.

Sputum cytology or microbiological cultures can identify infections or malignant cells shed into the airways. In cases where pneumonia is suspected, sputum analysis is essential.

When stages cancer are advanced, and cough is likely multifactorial, a multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, pulmonologists, and infectious disease specialists ensures accurate diagnosis and care.

Treatment and Symptom Relief for Chronic Cough in Lung Cancer

Managing chronic cough in male lung cancer patients requires a multifaceted approach. The primary goal is to reduce the frequency and severity of cough while addressing underlying causes and preserving quality of life.

Pharmacological interventions include antitussives like dextromethorphan or codeine for symptomatic relief. Gabapentin or amitriptyline may be used for neurogenic cough, especially when centrally mediated.

Anti-inflammatory treatments, including corticosteroids or nebulized budesonide, are used when inflammation drives the cough—especially in immune-related pneumonitis. Antibiotics or antifungals are necessary if infection is confirmed.

Adjusting cancer therapy may also help. If immunotherapy is causing pneumonitis, a dose hold or discontinuation may be required. Radiation-induced cough may be alleviated by modifying dose or targeting regions more precisely.

Supportive care, including hydration, humidified air, and breathing exercises, can reduce throat irritation. In cases of airway obstruction, palliative bronchoscopy (e.g., stenting or laser debulking) may provide mechanical relief.

Referral to a cough clinic or palliative care specialist is often warranted for refractory cases, where cough persists despite optimal treatment of the underlying disease.

Can Chronic Cough in Lung Cancer Be Prevented?

While complete prevention of chronic cough in lung cancer may not be possible, several strategies can reduce its frequency, severity, or delay its onset. Prevention largely depends on proactive symptom management, early detection of complications, and careful coordination of cancer therapies.

Patients should attend all scheduled imaging and follow-up appointments. Monitoring tumor response to therapy allows oncologists to adjust treatment before it causes significant airway irritation. Avoiding overexposure to known irritants—like cigarette smoke, dust, or pollutants—is crucial, especially in male patients with pre-existing lung conditions.

Respiratory hygiene plays a role. Staying hydrated, practicing gentle airway clearance techniques, and using saline nebulizers may protect the mucosa. Regular oral hygiene can also prevent infections that trigger cough.

For those undergoing targeted or immune therapies, being alert to signs of pneumonitis or allergic reactions is critical. Reporting new or changing symptoms early can allow clinicians to act before a cough becomes debilitating.

Lifestyle adjustments—such as stress management, light aerobic exercise (as tolerated), and maintaining nutritional status—support overall lung function and immune resilience. These protective measures don’t eliminate risk, but they significantly enhance the patient’s ability to tolerate treatment and manage symptoms.

Does the Cough Eventually Go Away or Persist?

The course of chronic cough in male lung cancer patients varies based on cancer type, stage, treatment response, and individual physiology. Some men experience temporary coughing only during chemotherapy or radiation, while others struggle with persistent or lifelong symptoms.

For early-stage patients, especially those with Lung Cancer detected before airway invasion, cough may resolve completely after tumor resection or curative treatment. However, if the tumor is inoperable or located centrally, cough may remain due to scarring, inflammation, or airway collapse.

In more advanced cases—such as Stage III or IV disease—the cough tends to persist and may even worsen as cancer progresses. In those receiving palliative care, cough management becomes a core component of quality-of-life treatment.

Long-term remission cases still require monitoring, as radiation fibrosis, nerve damage, or lung function changes can leave residual cough. Thus, while cough may diminish with time or respond to treatment, complete and permanent relief is not always guaranteed.

What Oncologists Say About Managing Chronic Cough

Practicing oncologists emphasize a personalized and layered approach to managing chronic cough in men with lung cancer. According to Dr. H. Malik, a thoracic oncologist at the National Cancer Institute, “Persistent cough is not just a symptom—it’s often a clue. We always investigate whether it’s signaling tumor growth, inflammation, or drug reaction.”

He notes that ignoring the cough or simply masking it with over-the-counter suppressants can be risky. “A new or worsening cough in a patient with lung cancer must prompt re-evaluation. Sometimes we catch infections or metastatic changes early just because the cough didn’t behave normally.”

Dr. A. Jensen, a pulmonary oncologist, adds that communication is key: “Many men don’t report their symptoms until the cough is intolerable. I always encourage my patients to describe changes in cough pattern, especially if they notice blood, night worsening, or breathlessness.”

Both experts agree on integrating pulmonologists, radiologists, and palliative care professionals early in complex cases. Their coordinated insight leads to faster symptom relief and improves the patient’s physical and emotional well-being.

15+ Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Chronic Cough and Lung Cancer

1. What is causing my chronic cough?

Your doctor can help identify whether your cough is due to the tumor, treatment, infection, or another factor.

2. Could my cough be a sign of cancer progression?

This question allows for discussion of imaging and staging updates.

3. Should I worry about coughing up blood?

Even small amounts can be significant and warrant evaluation.

4. Are there medications to help reduce the cough?

Antitussives, anti-inflammatory agents, or neuropathic treatments may be suggested.

5. Can adjusting my cancer treatment help my cough?

Modifying dose, timing, or switching therapies may reduce cough-inducing side effects.

6. What should I do if the cough suddenly worsens?

Knowing emergency signs helps patients act quickly.

7. Do I need a bronchoscopy or further imaging?

Advanced tests may clarify the cause of persistent cough.

8. Could I be experiencing radiation-induced lung changes?

This is important for patients with prior chest radiation.

9. What role does infection play in my symptoms?

Your oncologist may recommend cultures or empiric antibiotics.

10. Will my cough ever completely go away?

Set realistic expectations based on stage and treatment goals.

11. What supportive therapies can I try at home?

Humidifiers, breathing exercises, and voice therapy may help.

12. Should I see a cough or pulmonary specialist?

Referral to a pulmonologist may improve management of complex cases.

13. Can I still exercise or will that worsen my cough?

Your care team can guide you based on lung reserve and oxygenation.

14. How do I manage cough at night or during sleep?

Positioning and medications may improve nighttime relief.

15. What symptoms should I report immediately?

Being alert to red flags—like fever, chest pain, or stridor—is essential.