Back Pain in Adolescent Bone Cancer

Back Pain in Adolescent Bone Cancer: Understanding the Hidden Symptom

- Why Adolescents with Bone Cancer Often Experience Back Pain

- How Bone Cancer and Its Treatment Affect the Spine and Nervous System

- How Common Is Back Pain in Adolescents with Bone Cancer?

- What Causes Back Pain During Cancer or Its Treatment

- Red Flags: When Back Pain Signals Something Serious

- Diagnosing the Underlying Cause of Back Pain

- Medical and Supportive Therapies to Relieve Pain

- Is It Preventable? Managing Risk Factors in Cancer Care

- How Long Does the Pain Last—And Will It Go Away?

- What Oncologists Say About Back Pain in Young Bone Cancer Patients

- Key Questions to Ask Your Medical Team

- 15+ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Why Adolescents with Bone Cancer Often Experience Back Pain

Back pain in adolescents is often dismissed as posture-related or sports-induced discomfort. However, in some cases, it can be a hidden early symptom of serious conditions like bone cancer. Adolescents, especially those in their growth spurts, may report vague aches that are easily attributed to normal development—but when these pains localize in the back and persist, they deserve careful attention.

In cases of primary bone cancer like osteosarcoma or Ewing sarcoma, back pain may arise when tumors develop in the spine or pelvis, or metastasize to spinal regions. The pain may initially mimic muscle strain, but it often intensifies over time, disrupts sleep, or is not relieved by rest. Unlike common mechanical pain, this discomfort may worsen at night and gradually become more focal and deep-seated.

Parents and physicians should remain alert when adolescents complain of back pain that is persistent, progressive, or accompanied by other systemic signs such as weight loss, fatigue, or unexplained fever. Recognizing these patterns early can significantly influence treatment outcomes.

How Bone Cancer and Its Treatment Affect the Spine and Nervous System

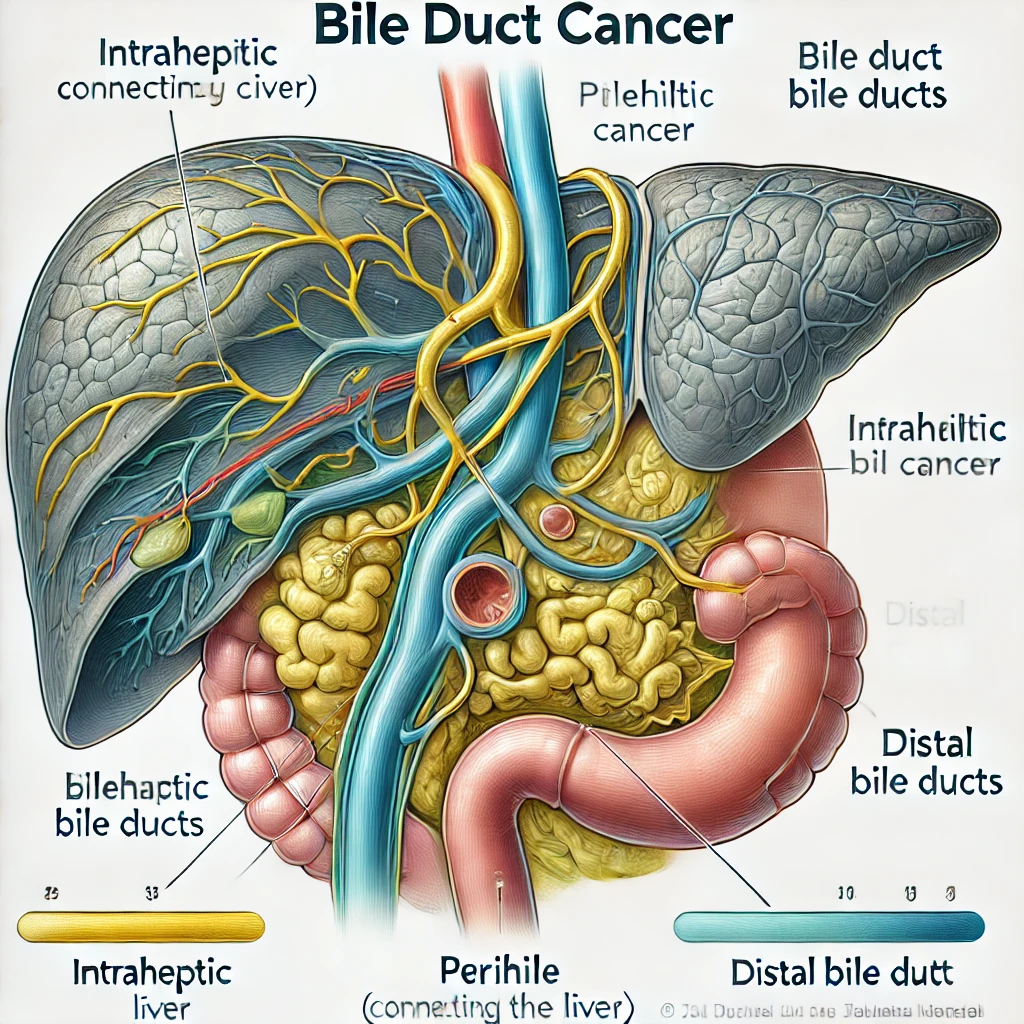

The mechanism behind back pain in adolescent bone cancer involves multiple layers of interaction between the tumor and surrounding structures. If the cancer originates in vertebral bones or nearby pelvic regions, it may directly infiltrate nerve roots or compress the spinal cord. This can lead to neurological symptoms in addition to pain, including numbness, weakness, or altered gait.

Even tumors not initially located near the spine can metastasize, particularly in aggressive subtypes. For example, Ewing sarcoma, which often begins in long bones or pelvis, has a high likelihood of spreading to the lungs or spinal areas. Once in the vertebrae, it can disrupt structural integrity, cause vertebral collapse, or irritate nerve endings—resulting in intense, unrelenting pain.

Moreover, cancer treatment itself can contribute to back discomfort. Chemotherapy may weaken bones, while radiation therapy to spinal regions can inflame tissue or accelerate degenerative changes. In some cases, long-term steroid use can lead to osteoporosis or avascular necrosis, which may also provoke back symptoms.

Understanding the relationship between tumor behavior and spinal involvement is essential for early intervention and pain management, especially when the adolescent’s physical development and future mobility are at stake.

How Common Is Back Pain in Adolescents with Bone Cancer?

Back pain is not the most common presenting symptom in adolescents with bone cancer, but when it does occur, it often indicates either spinal tumor involvement or metastatic progression. In clinical studies, only about 10–15% of patients with primary bone tumors report back pain at initial diagnosis. However, the percentage rises significantly—to nearly 40%—in patients with confirmed spinal metastases.

Among those with Ewing sarcoma, the incidence of spinal or pelvic pain is notably higher due to the tumor’s tendency to affect flat bones and soft tissues. In contrast, osteosarcoma more commonly begins in long bones (like the femur or humerus) and is less frequently associated with back pain unless metastasis occurs.

A key clinical observation is that symptoms cancer in adolescents often overlap with benign complaints—so back pain as a red flag is frequently missed until imaging or biopsy confirms the diagnosis. This delay can be critical. In one retrospective cohort, the average time from first symptom to diagnosis was over three months, during which the pain gradually worsened or changed in nature.

Therefore, while back pain may not be the most obvious warning sign of bone cancer, its presence—especially when persistent—should prompt investigation rather than be attributed to lifestyle or posture alone.

What Causes Back Pain During Cancer or Its Treatment

Several oncologic, pharmacologic, and metabolic mechanisms contribute to the development of back pain in adolescents diagnosed with bone cancer. Some causes are directly tumor-related, while others arise from the body’s response to treatment.

Oncologic factors include:

- Tumor invasion into vertebral bone or paraspinal soft tissue

- Compression or irritation of spinal nerves

- Metastasis to spine or pelvis

Medication-related causes include:

- Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy (e.g., from vincristine)

- Steroid-induced bone loss or vertebral fractures

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (paradoxical pain sensitivity)

Metabolic contributors:

- Electrolyte imbalances (e.g., hypocalcemia) affecting nerve conduction

- Anemia-related ischemia, which can increase fatigue and somatic discomfort

- Vitamin D deficiency from limited sun exposure or poor nutrition

In some cases, musculoskeletal factors play a secondary role. Adolescents may develop postural strain or muscle imbalance as a result of immobility, prolonged bed rest, or compensatory movement patterns due to tumor-related pain. These mechanical issues can then overlay the original cancer-related discomfort, compounding the intensity of back pain.

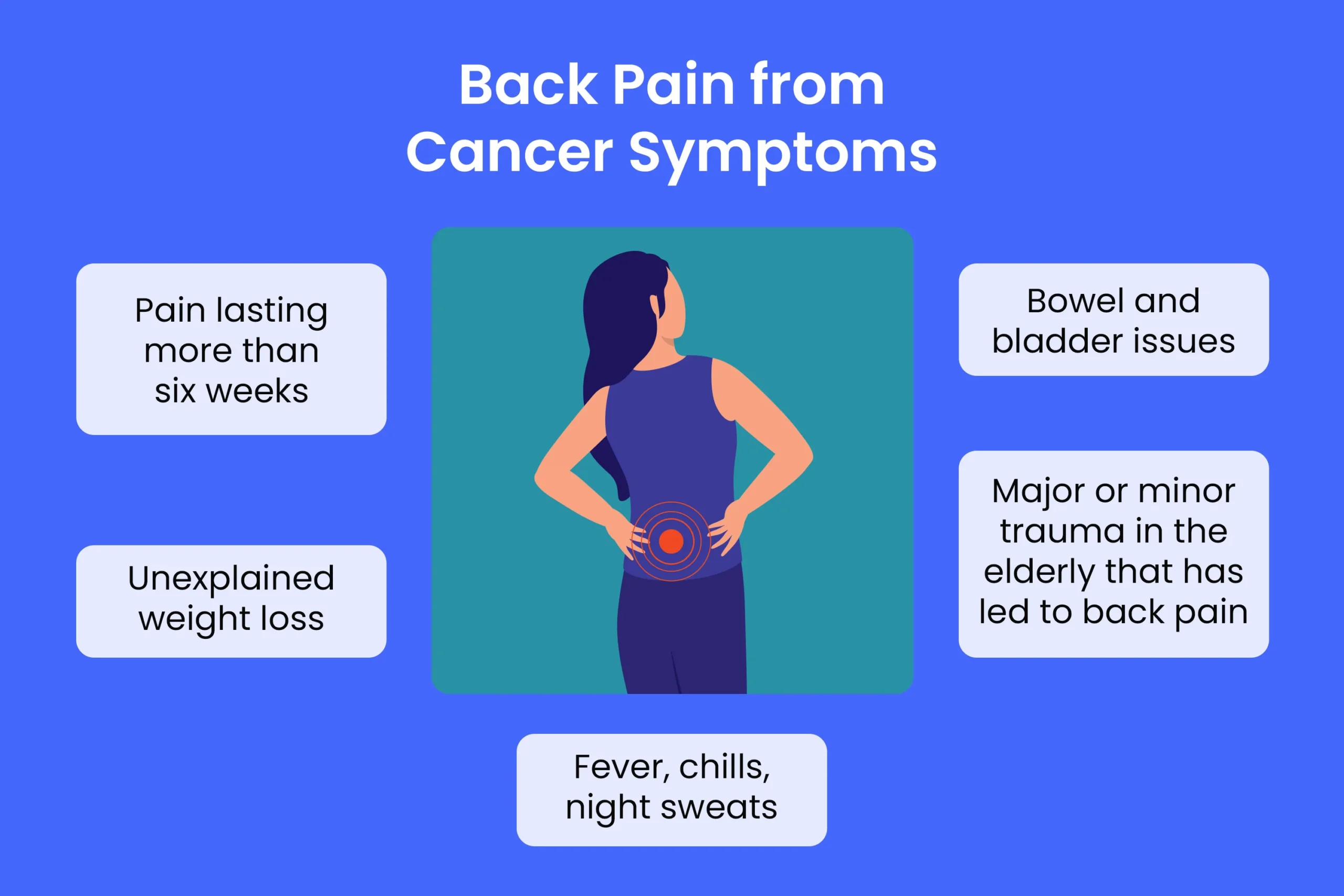

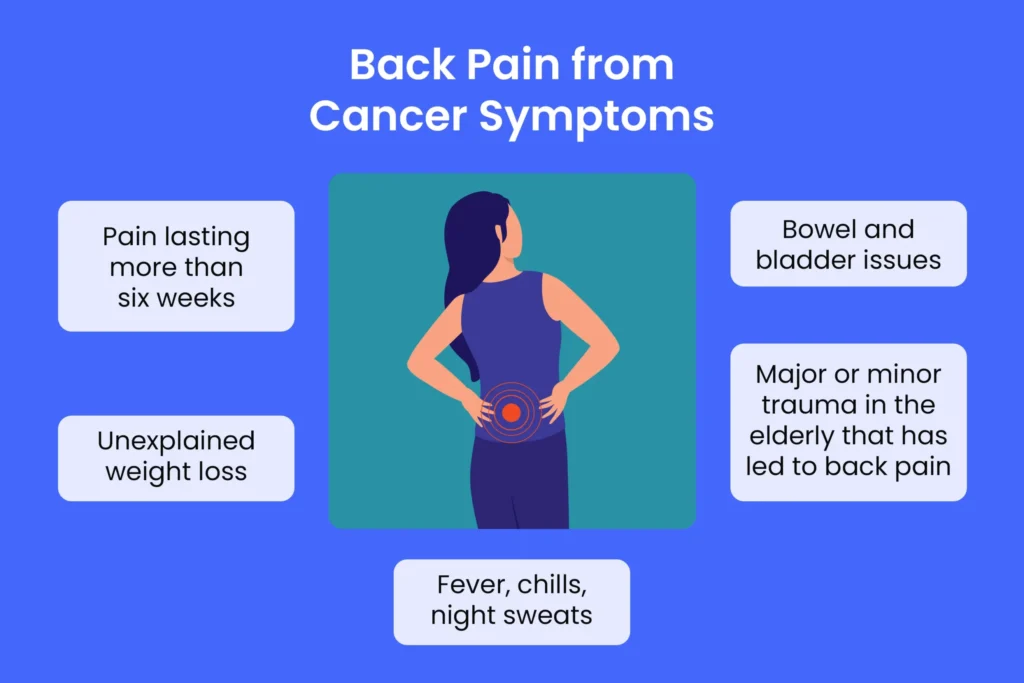

Red Flags: When Back Pain Signals Something Serious

While mild back discomfort is common in teenagers due to growth and posture, certain signs strongly suggest a more serious underlying issue—particularly in the context of known or suspected cancer. Recognizing these red flags can prompt early diagnosis and prevent irreversible complications.

Persistent back pain that lasts more than two weeks, especially without relief from rest or over-the-counter medication, is a significant warning sign. This is especially concerning if the pain is deep, localized, or worse at night—features uncommon in typical musculoskeletal strain.

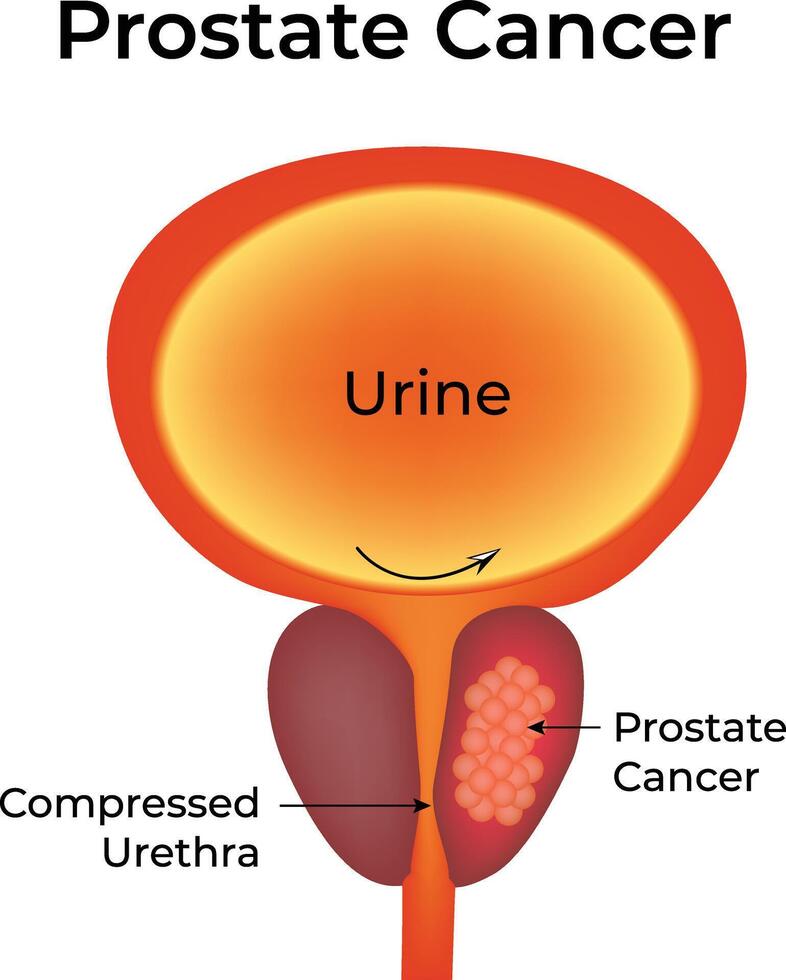

Neurological changes such as leg weakness, numbness, tingling, or difficulty walking may indicate spinal cord compression. In adolescents, even subtle gait changes or complaints of “legs feeling heavy” could signal tumor encroachment on neural pathways.

Systemic symptoms like unexplained fever, significant weight loss, fatigue, or night sweats—together with back pain—should immediately raise suspicion of a malignant process. In the setting of bone cancer, these are red flags not to be ignored.

Lastly, pain that progressively worsens despite conservative treatment, or recurs after initial improvement, may suggest either tumor growth or treatment-related complications like vertebral fractures. In such cases, urgent imaging is essential to rule out progression or structural instability.

Diagnosing the Underlying Cause of Back Pain

Pinpointing the source of back pain in adolescents with bone cancer requires a combination of clinical assessment and advanced imaging techniques. A thorough diagnostic approach not only identifies the cause but also guides timely and targeted treatment.

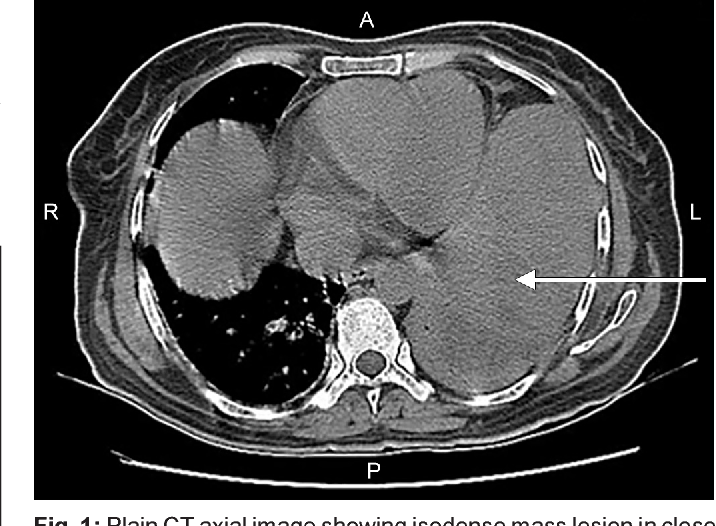

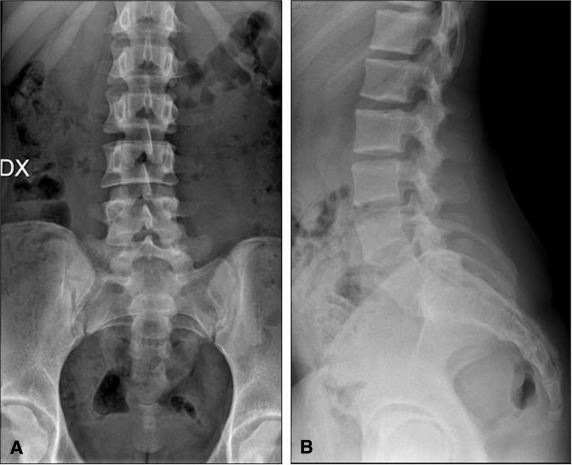

The evaluation begins with a full physical and neurological exam. Physicians assess posture, range of motion, tenderness, and any signs of nerve involvement. If cancer is suspected or already diagnosed, imaging is the next step.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is the gold standard for evaluating spinal and soft tissue structures. It can detect tumor infiltration, edema, nerve root compression, and early vertebral collapse. Computed Tomography (CT) scans offer detailed images of bone architecture and help assess for structural damage or fractures.

Bone scans and PET scans are commonly used to detect metastatic spread or identify other skeletal sites involved in the cancer. In some cases, a biopsy may be necessary to confirm whether spinal lesions are malignant, inflammatory, or treatment-related.

Laboratory tests are also valuable. Blood panels can uncover anemia, inflammation markers, or metabolic imbalances that may contribute to generalized discomfort. In patients with neurological symptoms, a lumbar puncture may be considered to check for malignant cells in cerebrospinal fluid.

By combining these diagnostic tools, clinicians can distinguish between pain caused by tumor, treatment, or secondary mechanical strain—each of which requires a different therapeutic approach.

Medical and Supportive Therapies to Relieve Pain

Treating back pain in adolescents with bone cancer requires a multidisciplinary strategy that addresses both the root cause and symptomatic relief. While the primary goal is tumor control, effective pain management is crucial for maintaining quality of life and functional independence.

Pharmacological treatment typically starts with non-opioid analgesics like acetaminophen or NSAIDs (if tolerated). If pain persists or is severe, opioid therapy may be introduced with careful dosing to avoid dependence and monitor for side effects.

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone are commonly used to reduce tumor-induced inflammation and spinal cord compression. For neuropathic pain, medications like gabapentin or amitriptyline may be added to modulate nerve signaling.

Radiation therapy plays a role in cases where tumors are compressing the spine or causing intractable pain. It can shrink lesions and reduce pressure on nerves. Surgical intervention may be considered in rare cases of spinal instability or fracture.

Supportive therapies are equally important. Physical therapy helps restore mobility and correct imbalances caused by postural strain or muscle atrophy. Psychological support addresses emotional stress, which often amplifies pain perception—especially in adolescents navigating a cancer diagnosis.

Palliative care specialists are frequently involved, even during curative treatment phases, to ensure that pain is addressed holistically, combining medication, rehabilitation, and emotional support.

Is It Preventable? Managing Risk Factors in Cancer Care

While not all cancer-related back pain is preventable, several strategies can significantly reduce the risk of its development or severity in adolescents with bone cancer. These preventive efforts often focus on early detection, skeletal protection, and lifestyle adaptations during treatment.

Monitoring for symptoms cancer—including subtle back aches or posture changes—can lead to earlier diagnosis of tumor spread or treatment complications. Educating patients and caregivers to report new or changing pain patterns is essential.

Preventing treatment-related causes of back pain involves proactive management of side effects. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation may help preserve bone strength during chemotherapy or steroid use. Regular weight-bearing exercises (within safety limits) can also maintain muscle support and spinal alignment.

For patients on long-term therapy, periodic imaging can monitor for signs of spinal instability, especially if the cancer involves the pelvis or vertebral bodies. Intervening early in cases of minor compression can prevent major neurological compromise.

Encouraging proper ergonomics, supportive bedding, and movement routines—particularly during periods of hospitalization—further reduces the risk of secondary musculoskeletal pain. Though cancer itself cannot be entirely prevented, its spinal effects can often be mitigated through attentive, multidisciplinary care.

How Long Does the Pain Last—And Will It Go Away?

The duration and resolution of back pain in adolescents with bone cancer depend on several factors: the cancer’s stage, whether the spine is directly involved, the response to treatment, and the individual’s recovery capacity.

In early-stage cases where the spine is unaffected, any back pain linked to posture or treatment side effects often improves within weeks after therapy begins. Supportive care—like physical therapy and pain management—can accelerate this process.

However, when the pain originates from spinal tumors or metastases, the prognosis becomes more complex. Some patients experience substantial relief after radiation or chemotherapy shrinks the tumor. In these cases, the pain may resolve within months. Yet, if the cancer causes long-term nerve damage or structural instability, the pain may persist even after tumor control.

Pain related to vertebral fractures, degenerative changes from radiation, or steroid-induced bone weakening may also linger and require ongoing management. That said, with proper intervention, many adolescents regain full or near-full function and report little to no chronic pain over time.

Long-term outcomes improve when back pain is addressed early, treated comprehensively, and monitored closely throughout and after cancer therapy. In cases where pain remains, adolescent patients may benefit from chronic pain rehabilitation programs and structured return-to-activity plans.

What Oncologists Say About Back Pain in Young Bone Cancer Patients

According to practicing pediatric oncologists, back pain in adolescents is often underrecognized as a serious symptom until more severe signs appear. Dr. Helen Morris, a pediatric oncology specialist, emphasizes: “Any back pain that lasts more than 10–14 days in a teen, especially with fatigue or night sweats, deserves further investigation. These aren’t growing pains—they could be symptoms cancer.”

Neuro-oncologists echo the concern, especially when back pain presents alongside gait changes or limb numbness. “Spinal involvement in bone tumors can be silent initially,” notes Dr. Eric Lu, “but by the time the patient can’t walk normally, we’re often dealing with advanced compression. Earlier imaging could change outcomes.”

Most specialists agree that pain is frequently underestimated in teens due to their stoicism or tendency to minimize symptoms. Oncologists encourage open communication with both adolescents and parents, and stress the importance of documenting even subtle symptoms over time.

Multidisciplinary tumor boards—including oncologists, neurologists, radiologists, and physiatrists—are often involved when back pain persists. They evaluate the pain not just as a side effect, but as a potential clinical signal requiring active intervention.

Key Questions to Ask Your Medical Team

Families navigating adolescent bone cancer often face uncertainty when back pain becomes part of the picture. Asking the right questions can help clarify the situation, set expectations, and ensure that nothing is overlooked. Consider bringing these questions to your oncologist or care team:

- Could the back pain be caused by spinal metastasis?

- What imaging tests are most appropriate for this type of pain?

- How can we distinguish between cancer-related pain and musculoskeletal pain?

- Is physical therapy safe during treatment?

- What medications are best for managing back pain without interfering with cancer treatment?

- Will the pain go away after therapy ends?

- Are there risks of long-term spinal damage?

- Could the treatment itself (chemotherapy, steroids, radiation) be worsening the back pain?

- Should we see a pain specialist or neurologist?

- Are there safe alternative therapies for pain, such as acupuncture or massage?

- How do we monitor for worsening neurological symptoms?

- What should we do if the pain returns after remission?

- Are there red flags that should prompt a trip to the emergency room?

- How can we manage the emotional stress associated with chronic pain?

- Will insurance cover supportive treatments like physiotherapy or counseling?

These questions help open a dialogue with the care team and make families feel more prepared and empowered.

15+ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is back pain a common first symptom of bone cancer in teens?

While not the most common, back pain can be an early warning sign, especially when tumors are located near or have spread to the spine. Persistent or night-worsening pain should not be ignored.

2. How is cancer-related back pain different from typical teenage back pain?

Cancer-related pain tends to be deeper, more persistent, and often occurs at night. It may also be accompanied by fatigue, weight loss, or neurological changes—unlike typical postural or activity-related discomfort.

3. What imaging is used to detect spine involvement in bone cancer?

MRI is the preferred method for evaluating soft tissue and nerve compression. CT scans help visualize bone structures. PET and bone scans are used for detecting metastasis.

4. Can physical therapy help with bone cancer back pain?

Yes—if prescribed appropriately. A physical therapist familiar with oncology cases can design a program that improves mobility and posture without worsening symptoms.

5. Is it safe to exercise during treatment?

In many cases, light to moderate activity is encouraged to maintain strength and prevent muscle atrophy. Always consult your oncologist or physiatrist for a tailored plan.

6. Do steroids cause back problems in bone cancer patients?

Long-term steroid use can weaken bones and increase the risk of vertebral fractures, which may contribute to back pain.

7. Can radiation make back pain worse?

Sometimes, especially in the short term. Inflammation after radiation may cause transient discomfort, but the pain typically improves once the tumor shrinks.

8. How can we tell if back pain is from metastasis?

If the pain is localized, progressively worsening, or associated with neurological changes (like leg weakness), imaging should be performed to check for metastasis.

9. Should we be concerned about back pain even if the primary tumor isn’t near the spine?

Yes. Tumors can spread hematogenously to the spine even if they start in long bones like the femur or tibia.

10. Can the pain go away after successful treatment?

In many cases, yes—especially if the pain was due to tumor pressure or inflammation. Some patients, however, may need long-term pain management if structural or nerve damage occurred.

11. What role does nutrition play in managing back pain?

Good nutrition supports healing, bone health, and muscle maintenance. Calcium, vitamin D, and protein are particularly important during treatment.

12. Are opioids the only option for pain relief?

No. Other medications, including anti-inflammatories, neuropathic agents, and complementary therapies, can be used alone or with opioids to control pain.

13. How do we prevent worsening back problems during treatment?

Monitor symptoms closely, avoid excessive bed rest, ensure spinal support with proper seating and sleep positions, and stay physically active when possible.

14. What mental health resources can help with pain-related distress?

Psycho-oncology services, child psychologists, and pain coping programs can help adolescents manage the emotional toll of chronic pain and cancer.

15. Who should manage ongoing back pain after cancer treatment ends?

A multidisciplinary team including oncologists, pain specialists, physiatrists, and mental health professionals can provide long-term follow-up and care.