Radiation Therapy for Colorectal Cancer

Radiation Therapy for Colorectal Cancer: Complete Patient Guide

- Understanding Colorectal Cancer and Treatment Pathways

- Types of Radiation Therapy Used for Colorectal Cancer

- How Radiation Is Combined with Chemotherapy

- Timing and Sequence of Radiation Therapy in Colorectal Cancer

- Radiation Side Effects: What to Expect During and After Treatment

- How Radiation Affects the Colon vs. the Rectum

- Advances in Radiation Technology for Precision Targeting

- Comparing Radiation Therapy to Chemotherapy and Surgery

- When Is Re-Irradiation Considered in Colorectal Cancer?

- Palliative Radiation for Symptom Relief

- Psychological and Emotional Support During Radiation

- Lifestyle Adjustments During and After Radiation

- Comparing Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy

- Long-Term Outcomes After Radiation Therapy

- How Radiation Fits Into Colorectal Cancer Staging

- Future Directions in Colorectal Radiation Therapy

- 15+ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Understanding Colorectal Cancer and Treatment Pathways

Colorectal cancer originates in the colon or rectum and is commonly diagnosed in later stages when symptoms become more noticeable. Treatment often includes a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Radiation is especially critical in rectal cancer cases, where it may shrink tumors before surgery or destroy residual cancer cells afterward.

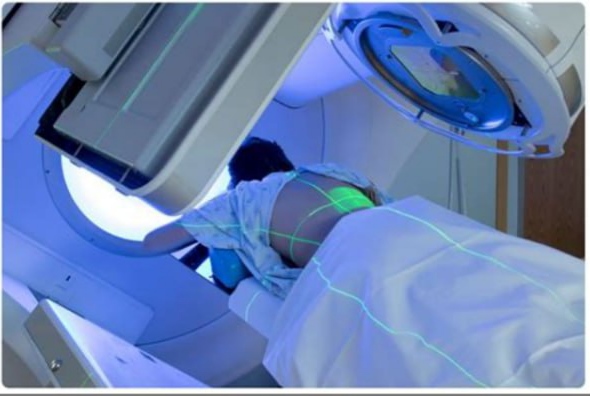

Radiation therapy involves using high-energy beams (usually X-rays or protons) to target and kill cancer cells. Its goal is to destroy the DNA of malignant cells so they can’t divide and multiply. This treatment can be curative in early stages or palliative in advanced stages to relieve pain and symptoms.

In treatment planning, doctors consider several factors such as the stage, location of the tumor, patient age, and whether lymph nodes or nearby tissues are involved. This determines whether radiation is delivered before surgery (neoadjuvant), after surgery (adjuvant), or used as the primary therapy when surgery isn’t feasible.

Types of Radiation Therapy Used for Colorectal Cancer

The two primary forms of radiation therapy used for colorectal cancer are external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and brachytherapy (internal radiation). EBRT is by far the most common.

| Type of Radiation | Description | When Used |

| EBRT | Delivers targeted beams of radiation from outside the body to the tumor area. Often combined with chemotherapy. | Pre-surgery or post-surgery in rectal cancer. |

| Brachytherapy | Involves placing radioactive material inside or near the tumor. Not commonly used for colon cancer. | In select rectal tumors, especially when preserving rectal function is critical. |

EBRT is often guided by advanced imaging such as CT or MRI to shape the radiation field precisely. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and 3D-conformal techniques further limit exposure to healthy tissue, especially vital in the pelvis where the bladder, reproductive organs, and bowel are nearby.

How Radiation Is Combined with Chemotherapy

In many cases, radiation therapy is paired with chemotherapy in a combined approach known as chemoradiation. This pairing has a synergistic effect: chemotherapy weakens cancer cells, making them more susceptible to the damage caused by radiation.

This is especially common in rectal cancer, where preoperative chemoradiation can shrink tumors, allowing for less invasive surgery and better sphincter preservation. Chemoradiation is also used postoperatively to target microscopic residual disease in the surrounding lymphatic tissue.

The typical chemotherapy drug used alongside radiation is 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or its oral counterpart capecitabine. These agents sensitize the tumor to radiation, but they also increase side effect risks, including fatigue, skin reactions, diarrhea, and changes in blood counts.

Timing and Sequence of Radiation Therapy in Colorectal Cancer

Timing is a crucial factor in colorectal cancer treatment. The sequence of radiation therapy depends on tumor location and overall staging. Here’s how it’s typically structured:

| Stage | Common Radiation Timing | Purpose |

| Stage II/III Rectal Cancer | Before surgery | Shrink tumor, improve surgical outcomes |

| Stage II/III Colon Cancer | Rarely used pre-surgery | More commonly after surgery for lymph node involvement |

| Stage IV (Metastatic) | As needed | Palliative for symptom relief |

Radiation may also be applied in a re-treatment scenario, known as re-irradiation, in cases of local recurrence. The safety and feasibility of this approach depend on prior dosage and time elapsed since the first treatment.

The delay between radiation and surgery—usually 6 to 12 weeks—allows the full effect of treatment to take place. This can improve outcomes by increasing the chance of a complete response, which means no viable tumor cells are found in the surgical specimen.

Radiation Side Effects: What to Expect During and After Treatment

Radiation therapy, while effective, can lead to several side effects—especially when targeting the pelvic region in colorectal cancer. These effects can be acute (during or shortly after treatment) or late-onset (appearing months or years later).

Common short-term effects include:

- Fatigue that worsens over time

- Diarrhea or bowel frequency changes

- Skin irritation or peeling near the radiation site

- Rectal bleeding or discomfort

- Bladder urgency

Potential long-term effects may involve:

- Bowel obstruction or chronic inflammation

- Sexual dysfunction

- Infertility

- Pelvic bone weakening

Managing these symptoms requires collaboration with a multidisciplinary team, including oncologists, gastroenterologists, nutritionists, and pelvic floor therapists. Patients are advised to maintain hydration, avoid spicy or high-fiber foods during treatment, and report any worsening symptoms.

How Radiation Affects the Colon vs. the Rectum

Radiation therapy is far more commonly used in rectal cancer than in colon cancer due to anatomical and functional differences. The colon is more mobile and less constrained within the pelvis, making it harder to target precisely without affecting other organs. In contrast, the rectum is a fixed structure in a confined space, making it a more accessible and effective radiation target.

This difference in location leads to:

- Higher preoperative radiation usage in rectal cancer

- More frequent use of surgery without radiation in colon cancer

- Greater risk of pelvic side effects in rectal cancer patients

However, there are exceptions. If colon cancer invades surrounding tissues or lymph nodes, radiation may be considered postoperatively. In these cases, radiation helps prevent local recurrence but carries increased risks, especially when delivered near small intestines or reproductive organs.

Advances in Radiation Technology for Precision Targeting

Modern radiation oncology has made enormous strides in improving precision and reducing collateral damage. Technologies such as IMRT (Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy) and IGRT (Image-Guided Radiation Therapy) allow doctors to tailor radiation beams with pinpoint accuracy.

These techniques help protect sensitive tissues like the bladder, prostate, uterus, and small bowel. Other innovations include:

- Proton therapy: Delivers radiation with minimal exit dose, preserving more healthy tissue. Still rarely used due to high costs.

- Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT): High-dose, short-course radiation that’s highly targeted, often used in recurrent or inoperable tumors.

With real-time imaging and dose modulation, radiation oncologists now adjust for breathing, organ motion, and tumor shrinkage over time—maximizing treatment success.

Comparing Radiation Therapy to Chemotherapy and Surgery

Radiation therapy is not a standalone treatment in most colorectal cancer cases—it works best when integrated into a multimodal approach. Here’s how it compares:

| Modality | Role | Strengths | Limitations |

| Surgery | Primary curative tool | Removes visible tumor | Not useful for microscopic spread |

| Chemotherapy | Systemic treatment | Targets metastases | Less effective at local control |

| Radiation | Local/regional control | Shrinks tumors, reduces recurrence | Less effective alone in late stages |

In rectal cancer, the gold-standard approach is neoadjuvant chemoradiation followed by surgery, particularly for stage II–III. For colon cancer, radiation is used more selectively and often in recurrence or palliation.

In rare cases where a patient cannot undergo surgery, radiation with or without chemotherapy may be the only treatment. This highlights the need for personalized planning based on tumor characteristics, patient fitness, and goals of care.

When Is Re-Irradiation Considered in Colorectal Cancer?

Re-irradiation refers to giving radiation therapy to a region that has previously received radiation. In colorectal cancer, this is considered only in highly selected cases, such as local recurrence where no other curative options exist.

The key factors influencing re-irradiation decisions include:

- Time elapsed since the first radiation course (typically ≥6 months)

- Original radiation dose and area

- Current tumor size and location

- Patient’s general health and prior treatment tolerance

Re-irradiation is performed cautiously due to the increased risk of severe complications like bowel perforation, chronic pain, and pelvic fibrosis. New techniques like proton beam therapy or IMRT allow for safer re-treatment by sparing more normal tissue.

Palliative Radiation for Symptom Relief

Not all radiation therapy in colorectal cancer is intended to cure. In advanced or metastatic cases, palliative radiation is used to relieve symptoms such as:

- Rectal bleeding

- Pain from pelvic or bone metastases

- Obstruction of the bowel or urinary tract

- Pressure on spinal nerves or blood vessels

The goal is comfort, not cure. Palliative courses are shorter—typically 1 to 10 sessions—and use lower total doses. While not curative, this approach can greatly improve quality of life for patients with limited treatment options.

It’s often combined with systemic treatments like chemotherapy or immunotherapy, depending on the spread of the disease.

Psychological and Emotional Support During Radiation

Undergoing radiation therapy can be mentally and emotionally taxing. Patients may experience anxiety, fear of recurrence, body image concerns, and fatigue. Providing comprehensive support is essential to treatment success.

Helpful strategies include:

- Counseling or therapy for anxiety and depression

- Patient support groups, online or in person

- Regular updates from the care team to manage expectations

- Physical activity to combat fatigue

- Maintaining a journal to track symptoms and emotions

Social workers and psychologists on oncology teams help patients process fear and grief while navigating financial or logistical challenges. Compassionate, holistic care is just as important as technical precision.

Lifestyle Adjustments During and After Radiation

Radiation therapy often requires temporary changes to daily habits to reduce complications and support recovery. Some of the most helpful lifestyle tips include:

- Diet: Eat smaller, low-fiber meals to minimize bowel irritation

- Hydration: Drink plenty of fluids to reduce urinary discomfort

- Rest: Plan extra time for rest and limit strenuous activities

- Skin care: Gently clean the radiation area with lukewarm water, avoid perfumes or tight clothing

- Stress management: Practice meditation, light stretching, or deep breathing

Long-term survivors should also consider incorporating an anti-inflammatory diet, maintaining a healthy weight, and undergoing regular colonoscopies to monitor for recurrence or second cancers.

Comparing Radiation Therapy and Chemotherapy

While both radiation and chemotherapy are used to treat colorectal cancer, they serve different purposes and are often used together in multimodal treatment plans.

| Aspect | Radiation Therapy | Chemotherapy |

| Target | Local (specific tumor area) | Systemic (whole body) |

| Common Use | Rectal cancer, symptom relief | Colon cancer, micrometastases |

| Delivery | External beam or internal (brachytherapy) | IV, oral, or via port |

| Side Effects | Skin irritation, pelvic discomfort | Fatigue, nausea, immune suppression |

| Timing | Before or after surgery (neoadjuvant/adjuvant) | Before, after, or instead of surgery |

For rectal cancers, radiation is almost always part of the treatment. For colon cancers, chemotherapy is usually favored unless there’s a need for local control or palliation.

Long-Term Outcomes After Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy plays a crucial role in improving long-term outcomes, especially in locally advanced rectal cancer. When used preoperatively, it can significantly reduce the risk of local recurrence and improve disease-free survival.

Key outcome measures include:

- Local recurrence rate: reduced from 25% to under 10% with radiation

- 5-year survival: can reach up to 70–75% in selected rectal cancer patients

- Bowel function: may be altered long-term, especially if surgery follows

- Second cancers: rare but possible; long-term monitoring is advised

Radiation therapy is continually evolving, with modern techniques like image-guided and adaptive radiotherapy helping to reduce complications and preserve quality of life.

How Radiation Fits Into Colorectal Cancer Staging

Colorectal cancer staging guides treatment planning. Radiation is generally used for stage II and III rectal cancer, less often for colon cancer.

Here’s how it fits:

- Stage 0–I: Surgery alone is often enough

- Stage II (rectal): Preoperative radiation reduces recurrence

- Stage III: Chemoradiation followed by surgery

- Stage IV: Palliative radiation for metastase

Correct staging often relies on imaging (CT, MRI, PET) and biopsy. Radiation may be re-evaluated if the cancer progresses or recurs after initial treatment.

Future Directions in Colorectal Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is rapidly advancing. Some promising innovations include:

- Proton therapy for more precise targeting with fewer side effects

- MRI-guided radiotherapy for real-time adaptation

- Hypofractionation (fewer sessions at higher doses)

- Artificial intelligence for personalized radiation plans

- Integration with immunotherapy, especially in mismatch repair–deficient tumors

Clinical trials continue to explore how to balance radiation dose, reduce toxicity, and improve survival. As we understand more about tumor biology, radiation will likely become more tailored and biologically guided.

15+ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Is radiation always necessary for rectal cancer?

No, but for stage II and III cases, it is commonly used before surgery to shrink the tumor and reduce recurrence risk.

2. How many sessions of radiation are typical?

Most standard radiation courses involve 25–30 sessions over 5–6 weeks, though short-course options also exist.

3. Will radiation therapy cause me to lose bowel control?

Some patients experience temporary urgency or incontinence, but permanent bowel dysfunction is uncommon with modern techniques.

4. Can I work while undergoing radiation?

Many people continue working, but fatigue and digestive discomfort may make it harder to maintain full-time hours.

5. Is radiation used for colon cancer too?

Not routinely, except in rare cases where the tumor invades adjacent organs or for palliation.

6. How does radiation affect the immune system?

Pelvic radiation has limited systemic effects, but can mildly suppress local immune function temporarily.

7. Will I lose my hair from pelvic radiation?

No, only the area treated is affected. Scalp hair is not impacted by colorectal radiation therapy.

8. Is it safe to have sex during radiation treatment?

It can be, but discomfort and emotional strain may reduce interest. Discuss specific concerns with your doctor.

9. What’s the risk of infertility?

Radiation may affect fertility in both men and women. Fertility preservation options should be explored beforehand.

10. Can radiation cure colorectal cancer alone?

Radiation is most effective when combined with surgery and/or chemotherapy for curative intent.

11. Are there permanent side effects?

Most side effects resolve, but rare cases of chronic bowel, bladder, or sexual dysfunction may occur.

12. How soon after radiation can surgery happen?

Surgery usually follows radiation after 6–12 weeks to allow tumor shrinkage and tissue recovery.

13. Does insurance cover radiation for colorectal cancer?

In most countries, yes—especially when used as part of standard cancer protocols.

14. Can I travel during treatment?

Short local travel is possible, but radiation requires near-daily attendance, which makes long trips difficult.

15. What’s the cost of radiation therapy?

In the U.S., full courses can cost tens of thousands of dollars without insurance. Financial aid may be available.