C-Reactive Protein Blood Test

C-Reactive Protein Blood Test: Its Role in Cancer Detection

- What Is the C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Test?

- How CRP Relates to Inflammation and Tumor Progression

- Clinical Use of CRP in Oncology Practice

- Cancers Most Commonly Associated with Elevated CRP Levels

- Interpreting CRP Results in the Context of Cancer

- CRP in Combination with Other Blood-Based Tumor Markers

- High-Sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) and Cancer Prediction

- CRP and Its Use in Cancer Staging and Prognosis

- Role of CRP in Monitoring Treatment Response

- CRP in Detecting Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis

- Current Research and Emerging Insights on CRP and Cancer

- Educating Patients on CRP: What They Should Know

- Comparing CRP with Other Cancer Biomarkers

- When Should CRP Be Ordered for Cancer Patients?

- How to Interpret CRP Results in Cancer Context

- Link Between CRP and Long-Term Outcomes in Cancer

- FAQ: C-Reactive Protein Blood Test and Cancer

What Is the C-Reactive Protein (CRP) Test?

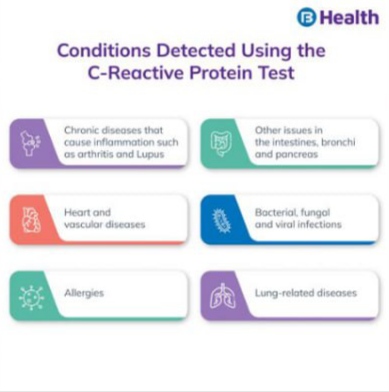

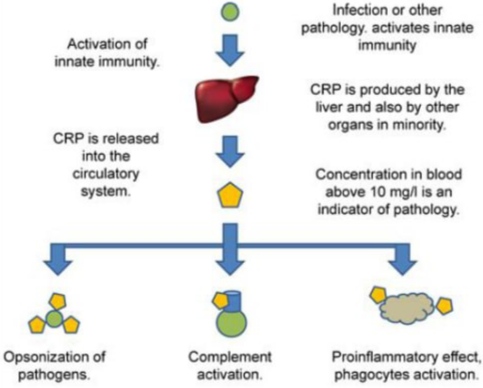

The C-reactive protein (CRP) test is a blood test that measures the concentration of CRP, a substance produced by the liver in response to inflammation. While CRP is not specific to any one disease, elevated levels can indicate a variety of health issues — from infections to autoimmune diseases and even cancer.

In healthy individuals, CRP levels are generally low. However, when inflammation occurs in the body, CRP production ramps up. The test is simple and minimally invasive, requiring only a small blood sample. It’s typically ordered when doctors suspect an underlying condition that triggers systemic inflammation. This includes diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular disease, and certain types of cancer.

Because cancer often involves chronic inflammation, CRP levels can serve as a valuable biomarker. However, it is important to note that CRP is not used to diagnose cancer on its own. Instead, it contributes to a broader diagnostic picture when combined with other clinical findings and tests.

How CRP Relates to Inflammation and Tumor Progression

Chronic inflammation plays a well-established role in cancer biology. Tumors can create an inflammatory microenvironment that promotes their growth, angiogenesis (blood vessel formation), and ability to metastasize. This inflammatory environment leads to increased CRP levels in the bloodstream.

High CRP levels may correlate with:

- Tumor burden (how much cancer is in the body)

- Disease stage and aggressiveness

- Poorer prognosis in several cancers, including colorectal, pancreatic, lung, and breast cancer

In essence, CRP acts as a nonspecific but reliable marker for tracking inflammatory activity related to malignancy. Studies have shown that patients with consistently elevated CRP tend to have worse outcomes than those with normal or fluctuating levels. While this doesn’t confirm cancer presence, it may warrant further testing when combined with symptoms and other markers.

Interestingly, some types of inflammation-induced cancer may arise from previously non-cancerous chronic conditions. For instance, the liver inflammation seen in hepatitis can eventually lead to liver cancer. In these scenarios, CRP values often reflect the persistent inflammatory response driving cancerous transformation.

Clinical Use of CRP in Oncology Practice

Doctors may use CRP results in oncology in several practical ways:

- Assessing Cancer Risk: For patients with a history of chronic inflammation or conditions like ulcerative colitis, a high CRP might suggest closer surveillance for malignancy.

- Monitoring Treatment Response: In certain cancers, falling CRP levels can indicate that treatment — such as chemotherapy or immunotherapy — is effectively reducing tumor activity.

- Predicting Outcomes: Persistently high CRP levels are often associated with worse outcomes. For example, in lung and colorectal cancers, elevated CRP before surgery or chemotherapy has been linked with reduced survival rates.

- Identifying Recurrence: A sudden spike in CRP post-treatment may prompt physicians to investigate for possible tumor recurrence.

Here’s a simplified overview table used in clinical tracking:

| CRP Level | Interpretation in Oncology Context |

| <1 mg/L | Normal, low inflammation |

| 1–10 mg/L | Mild inflammation, possibly non-cancer related |

| 10–40 mg/L | Moderate inflammation; could suggest tumor progression |

| >40 mg/L | Significant inflammation; warrants additional testing |

These values should always be considered alongside other tests like imaging, biopsy, or tumor markers (e.g., CEA or CA 19-9).

Cancers Most Commonly Associated with Elevated CRP Levels

Although CRP is nonspecific, some cancer types frequently exhibit high CRP levels during their course. These include:

- Colorectal Cancer: A strong body of evidence links high CRP to poorer prognosis. The inflammation from tumor invasion in bowel walls elevates CRP early in disease progression. This test often complements symptom of bowel cancer screening and may be followed by imaging or colonoscopy.

- Pancreatic Cancer: CRP levels may be elevated even in the early stages. A rise in CRP can support suspicion when patients report vague symptoms like fatigue or back pain.

- Lung Cancer: Chronic airway inflammation correlates with aggressive lung tumors. CRP here may also help differentiate between benign and malignant lung lesions.

- Breast Cancer: Inflammatory breast cancer and hormone-positive types sometimes demonstrate elevated CRP. It is used in risk assessment more than direct diagnosis.

- Lymphoma: Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas often present with systemic inflammation, where blood tests for lymphomas may include CRP as a secondary indicator.

In many cases, the test doesn’t confirm cancer but supports decision-making, especially in patients with risk factors or unexplained symptoms. Its strength lies in its sensitivity to ongoing inflammation, a hallmark of many cancers.

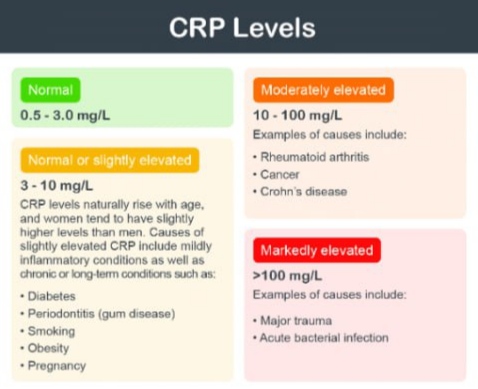

Interpreting CRP Results in the Context of Cancer

When evaluating CRP results, context is everything. A high CRP alone cannot confirm or rule out cancer, but it can direct clinicians toward further diagnostic investigation, especially if a patient presents with other signs or symptoms suggestive of malignancy.

Let’s break down what CRP readings might mean for a patient suspected of having cancer:

- Mildly Elevated CRP (1–10 mg/L): This could indicate early inflammatory activity, infection, or a pre-malignant condition. In some cases, this level is seen in smokers or individuals with metabolic syndrome.

- Moderately Elevated CRP (10–40 mg/L): Often warrants additional testing. If the patient reports unexplained fatigue, weight loss, or bleeding, this result may push the clinician to consider imaging or colonoscopy.

- Severely Elevated CRP (>40 mg/L): Associated with systemic inflammation — this may reflect late-stage or aggressive tumor growth, particularly if correlated with other abnormal labs or imaging findings.

Doctors also consider patient history (e.g., prior cancers, autoimmune diseases), physical examination findings, and concurrent test results. For example, an elevated CRP with high carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) might raise concern for colorectal cancer, while elevated CRP alongside abnormal blood smears could suggest lymphoma.

CRP’s role is not to diagnose, but to add clinical weight when the possibility of cancer is on the table — especially in combination with tumor markers and patient-reported symptoms.

CRP in Combination with Other Blood-Based Tumor Markers

CRP is often used in tandem with tumor-specific markers to enhance diagnostic accuracy and treatment planning. It doesn’t replace these markers but augments their interpretation.

Here’s how CRP compares and interacts with other markers in various cancers:

| Cancer Type | Tumor Marker | CRP Role |

| Colorectal | CEA | CRP helps assess inflammation, prognosis |

| Pancreatic | CA 19-9 | CRP supports disease monitoring |

| Ovarian | CA 125 | Elevated CRP may correlate with recurrence |

| Prostate | PSA | CRP adds inflammatory context to PSA changes |

| Lymphoma | LDH, beta-2 microglobulin | CRP indicates systemic response |

Using CRP alongside specific markers allows for better risk stratification. For example, in back ache and bowel cancer, a rise in CRP may indicate that pain isn’t just muscular — it could be linked to tumor spread or inflammation of the bowel wall.

The trend of CRP levels over time is particularly useful. A rising curve, even if gradual, may hint at progressing disease, while a steady decline often reflects effective treatment.

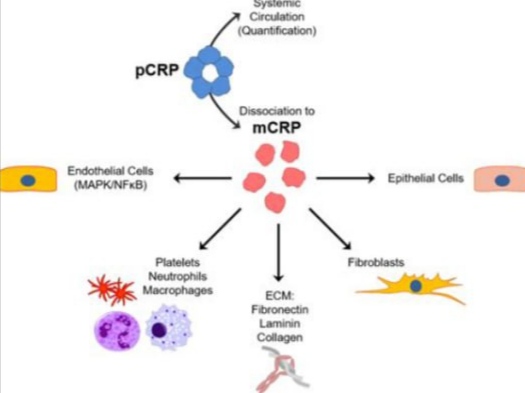

High-Sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) and Cancer Prediction

High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) tests can detect CRP levels as low as 0.3 mg/L — far below what standard CRP tests measure. Originally designed for cardiac risk assessment, hs-CRP has found applications in cancer screening and prevention research.

In oncology, hs-CRP may help:

- Identify cancer risk in asymptomatic individuals, especially those with obesity or chronic inflammation.

- Predict long-term outcomes in cancers like breast and prostate, where even low-grade inflammation can influence tumor behavior.

- Stratify risk in patients with borderline or ambiguous findings on imaging or biopsy.

A study in the Journal of Clinical Oncology linked elevated hs-CRP levels with increased breast cancer mortality, even after adjusting for stage and treatment. Another trial found that hs-CRP correlated with survival in pancreatic cancer, often providing prognostic value when CA 19-9 levels were ambiguous.

Still, it’s critical to emphasize that hs-CRP is not a screening tool for cancer by itself. It is best used to complement imaging and biopsy data, not to replace them.

CRP and Its Use in Cancer Staging and Prognosis

While CRP is not part of formal cancer staging (such as TNM classification), it plays a valuable supporting role in prognostic assessment. Elevated CRP levels may suggest:

- Higher tumor burden

- Presence of systemic inflammation

- Possible lymph node involvement

- Worse expected treatment response

In fact, some oncologists include CRP trends in their pre-treatment evaluation, particularly for GI and lung cancers. A patient newly diagnosed with stage III colon cancer and elevated CRP, for instance, may require more aggressive adjuvant therapy or closer monitoring than one with a normal CRP.

Additionally, CRP levels are often reviewed when considering surgery. If CRP is high in the absence of infection, this may prompt preoperative imaging to ensure the tumor hasn’t spread or caused complications like perforation or abscess — both of which are common in advanced bowel cancers. It’s especially relevant when assessing whether bowel leakage is a sign of cancer, as inflammation may drive both symptoms and CRP elevation.

Role of CRP in Monitoring Treatment Response

Once cancer treatment begins — whether surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or a combination — monitoring biomarkers becomes crucial. CRP is often used to track how a patient responds to therapy, especially in cancers known for systemic inflammation.

When CRP is monitored over time, its trajectory can tell physicians if the body is healing or if the cancer is progressing:

- Falling CRP levels post-treatment usually indicate that inflammation is resolving and the tumor burden is decreasing.

- Persistently elevated CRP may suggest incomplete tumor removal, lingering infection, or micrometastatic spread.

- Rising CRP during treatment could point to tumor resistance, treatment side effects (such as pneumonitis), or secondary issues like infection.

For example, in colorectal cancer management, CRP may drop following successful resection, then rise again months later — signaling a possible recurrence that imaging might still miss. It is often used alongside imaging, physical exams, and tumor markers like CEA.

In patients with lymphoma, CRP may decline with chemotherapy but spike with tumor lysis or inflammatory response to dying cells. Thus, clinicians interpret CRP dynamically, always correlating it with other clinical and lab findings.

CRP in Detecting Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis

CRP also plays a critical role in post-treatment surveillance. One of the challenges in oncology is detecting early signs of recurrence before symptoms arise or metastasis spreads too far. CRP trends help flag such issues:

- A slow, steady increase in CRP over several months, even within the upper-normal range, may precede radiographic evidence of relapse.

- In lung, bowel, and pancreatic cancers, sharp spikes in CRP can indicate new metastatic activity, especially in the liver or bones.

- For bowel cancer patients with back pain, an elevated CRP may point to metastatic deposits in the spine, requiring prompt imaging.

A well-structured follow-up plan may include CRP testing every 3–6 months in high-risk patients, particularly if they had elevated CRP at diagnosis or residual disease post-treatment.

CRP alone won’t detect recurrence — but when combined with patient history, complaints (like fatigue or pain), and other lab work, it becomes a powerful early-warning tool.

Current Research and Emerging Insights on CRP and Cancer

Ongoing studies are exploring CRP’s broader implications in cancer biology. Researchers are looking at whether CRP itself plays a role in tumor progression, not just as a passive indicator. Here are key findings from recent work:

- CRP and Cancer-Induced Cachexia: Elevated CRP is linked to muscle wasting and weight loss in late-stage cancer, suggesting it may drive metabolic imbalances.

- Genetic Variants in CRP Expression: Some patients have gene polymorphisms that lead to higher CRP production — even in the absence of disease. Understanding this helps prevent false alarms.

- Anti-inflammatory Therapy: Trials are underway to see if using drugs like statins or anti-cytokine agents to reduce CRP levels could improve survival in colorectal and lung cancer.

Moreover, inflammation — as reflected by CRP — is now being integrated into multifactorial risk prediction models. These models combine CRP, genetics, and lifestyle factors to estimate cancer development risk years before symptoms appear. This is especially relevant for detecting conditions like bowel cancer, where early signs might be subtle or overlap with benign issues like IBS.

Educating Patients on CRP: What They Should Know

Understanding CRP empowers patients to take an active role in their care. However, this biomarker can be confusing, especially when patients expect a “yes/no” answer and instead get a number like “7.2 mg/L.”

Key talking points for clinicians and patient educators include:

- CRP is a general marker, not a cancer test. It signals inflammation, not necessarily malignancy.

- CRP trends are more important than isolated results. A mild elevation isn’t alarming if it stays stable; a rising trend is more significant.

- Multiple factors influence CRP, including infections, injury, autoimmune conditions, obesity, and even intense exercise.

Clear communication avoids unnecessary anxiety. For example, if a patient recovering from colorectal surgery has a slightly elevated CRP but no symptoms, they should understand it could be part of healing — not a cancer return.

This is especially important when differentiating cancer symptoms from other GI disorders. A patient might wonder if their discomfort is due to inflammation or something more serious — such as bowel leakage being a sign of cancer. In that context, CRP helps determine whether further work-up is needed.

Comparing CRP with Other Cancer Biomarkers

CRP is just one part of a broader diagnostic landscape. In oncology, multiple blood tests are often used together to improve accuracy. Below is a comparison of CRP with commonly used tumor markers:

| Marker | Primary Use | Cancer Types | Limitations |

| CRP | Inflammation & general monitoring | All types (esp. GI, lung) | Non-specific, affected by many conditions |

| CEA | Monitoring tumor activity | Colorectal, lung, breast | May be normal in early-stage disease |

| CA-125 | Tumor detection & monitoring | Ovarian, endometrial | Elevated in benign conditions too |

| PSA | Prostate cancer screening | Prostate | Can yield false positives in BPH |

| LDH | Tumor burden & cell turnover | Lymphoma, melanoma, testicular | Not cancer-specific |

What sets CRP apart is its ability to reflect systemic burden and inflammatory microenvironment—factors often overlooked in standard oncology labs. For lymphoma patients, combining CRP with LDH and blood tests for lymphomas gives a more complete picture of disease dynamics.

When Should CRP Be Ordered for Cancer Patients?

While CRP isn’t a routine part of all cancer evaluations, here are scenarios when it is especially helpful:

- Unexplained weight loss or fatigue in a high-risk individual

- During initial cancer workup, especially when inflammation is suspected

- Following cancer treatment, to monitor inflammation and recovery

- When recurrence is suspected, especially in combination with rising CEA or CA-125

- In cachexia or treatment side effect evaluation, where inflammation may play a role

Clinicians should also consider CRP in cancer patients experiencing unusual pain, fever, or back ache, as this may signal hidden metastases or complications.

How to Interpret CRP Results in Cancer Context

Interpreting CRP values correctly is essential. Below is a simplified reference table tailored for cancer patients:

| CRP Level (mg/L) | Interpretation in Cancer Setting |

| <1.0 | Low inflammation; typical in remission or early disease |

| 1–5 | Mild elevation; may indicate early inflammatory response |

| 5–10 | Moderate; often seen post-treatment or in active disease |

| >10 | High; may suggest recurrence, progression, or infection |

| >50 | Very high; warrants urgent investigation |

Always assess CRP in relation to clinical signs and history. A reading of “8 mg/L” might not seem alarming alone, but if it was 2 mg/L a month ago and symptoms are worsening, it signals progression.

Patients should be reminded that CRP doesn’t diagnose cancer — it complements diagnostic and monitoring strategies, helping clinicians evaluate how the immune system is responding to underlying issues.

Link Between CRP and Long-Term Outcomes in Cancer

Several studies have linked chronic inflammation (measured by CRP) to poorer outcomes in cancer patients. Elevated CRP before or during treatment is often associated with:

- Shorter overall survival

- Lower response rates to chemotherapy

- Increased post-operative complications

- Higher recurrence risk

In colorectal and pancreatic cancers, pre-treatment CRP above 10 mg/L has been linked to worse prognosis — even in patients with otherwise localized disease.

This connection is now a subject of active research. Scientists are exploring whether controlling CRP with anti-inflammatory interventions could improve survival or treatment tolerance.

Some patients, especially those interested in preventative health or with family history, also look into how CRP fits into broader cancer prediction models. These models are often combined with data from tests that explore type of cancer causes low hemoglobin, or genetic predisposition to inflammation.

FAQ: C-Reactive Protein Blood Test and Cancer

1. Is CRP a cancer marker?

Not directly. CRP is a marker of inflammation, not cancer itself. However, cancer often causes inflammation, so elevated CRP can indirectly indicate cancer presence or progression.

2. Can high CRP mean cancer recurrence?

Yes, in some cases. A rising CRP level after treatment can suggest inflammation linked to recurrence. However, it must be interpreted alongside other tests and clinical signs.

3. Is CRP always elevated in cancer?

No. Some cancers, especially in early stages or indolent types, may not trigger significant CRP elevation. CRP is more useful in active or advanced disease.

4. Can CRP be used to monitor chemotherapy response?

It can. A falling CRP level during chemotherapy often reflects reduced tumor-related inflammation, which may indicate a positive response.

5. Does a low CRP level mean I’m cancer-free?

Not necessarily. A low CRP indicates little to no inflammation but does not rule out cancer. Some cancers grow silently without triggering immune response.

6. Can infections also raise CRP?

Absolutely. CRP is not specific to cancer. Infections, autoimmune diseases, and even minor injuries can elevate CRP.

7. How often should CRP be checked in cancer patients?

This depends on the cancer type and clinical scenario. Some oncologists check CRP monthly during treatment, while others only order it with symptom changes.

8. What’s the difference between CRP and ESR?

Both are inflammatory markers. CRP reacts quickly (within hours), while ESR is slower and influenced by more variables like age and anemia.

9. Can CRP detect cancer earlier than imaging?

In some cases, CRP can rise before a tumor becomes large enough to show on scans. But it’s not reliable enough to replace imaging for early detection.

10. Are CRP levels affected by diet or stress?

Yes. Obesity, chronic stress, and processed foods can raise CRP levels. A healthy lifestyle can help keep CRP lower.

11. Can CRP help differentiate between cancer types?

Not really. CRP reflects inflammation, not tumor origin. It can’t tell if the source is breast, colon, or another cancer. That requires other diagnostic tools.

12. How long after treatment does CRP normalize?

This varies. If treatment is successful and no inflammation remains, CRP may drop within days to weeks. Persistently elevated CRP may indicate complications or residual disease.

13. Does CRP play a role in cancer prevention?

Indirectly. Since inflammation is linked to cancer risk, keeping CRP low through anti-inflammatory diets and lifestyle changes may reduce cancer risk.

14. What is hs-CRP and is it different?

High-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP) detects low levels of inflammation, often used in heart disease risk. In cancer, regular CRP is usually sufficient.

15. Can I test CRP at home?

Not yet reliably. While some at-home kits exist, accurate CRP testing should be done in clinical labs for proper interpretation and medical context.