What Do Breast Cancer Metastases Look Like? Understanding Skin Spread

- Part 1: Why Understanding Skin Metastases Matters

- Part 2: What Skin Metastases from Breast Cancer Actually Look Like

- Part 3: How Skin Metastases Are Diagnosed

- Part 4: Treatment Options for Skin Metastases

- Part 5: Monitoring Progress and Recognizing New Changes

- Part 6: When Skin Metastases Progress Despite Treatment

- Part 7: Managing Symptoms and Supporting Quality of Life

- Part 8: Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

- Part 9: Practical Living with Skin Metastases

- Part 10: Final Thoughts and Summary

Foreword

If you or someone you love is facing breast cancer, hearing the word “metastasis” can feel overwhelming. When cancer spreads to the skin, it brings a new set of questions, fears, and realities. Some patients notice a lump or a patch and wonder if it means the cancer has returned. Others are living with visible lesions every day, trying to understand what these changes mean for their treatment and their future.

This article is here to walk you through that landscape — clearly, carefully, and with respect for what you’re going through. We’ll talk about what skin metastases from breast cancer really look like, how doctors diagnose them, what treatments are available, and how patients and families can navigate the emotional and practical challenges they bring.

There are no easy answers with metastatic cancer. But understanding what is happening, and what can still be done, helps turn fear into action. You deserve clear information, honest explanations, and compassionate care at every step. Let’s begin.

Part 1: Why Understanding Skin Metastases Matters

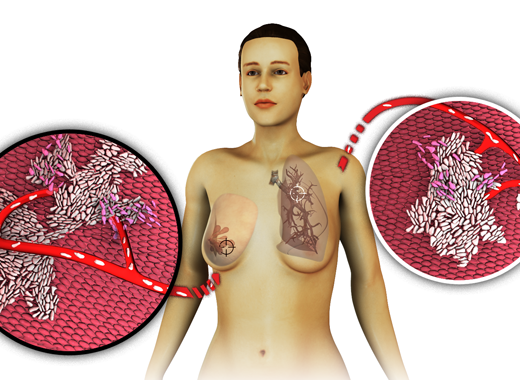

When we hear about breast cancer spreading, most of us immediately picture something internal — tumors deep in the liver, bones, or lungs. It’s less common to think about the skin. But for some people, breast cancer first announces its next chapter not with hidden symptoms, but right there, on the surface, where they can see it.

Maybe you’ve noticed a new patch of redness that doesn’t seem to heal. Maybe there’s a lump near the breast or chest wall that feels different from anything you’ve felt before. Maybe it’s not even on the breast anymore — maybe it’s a cluster of nodules across the abdomen, the back, or under the arm. If you’re seeing these things, it’s natural to feel a deep jolt of fear. What does this mean? Is it an infection? A rash? Or could it be something more serious?

Skin metastases from breast cancer — known medically as cutaneous metastases — are not the first thing doctors usually talk about. But they happen more often than most people realize, and when they do, they carry important information about the cancer’s behavior and stage.

You deserve to understand exactly what’s happening to your body. You deserve clear, compassionate explanations — not vague guesses or rushed reassurances. That’s what this guide is here for: to walk you through what breast cancer metastases to the skin can look like, how they behave, why they happen, and what steps you can take if you see changes that worry you.

This isn’t about scaring you. It’s about equipping you — calmly, honestly, and thoroughly.

Because the more you know, the stronger you stand.

Part 2: What Skin Metastases from Breast Cancer Actually Look Like

Skin metastases from breast cancer can present in several different ways, and understanding these patterns is important for early recognition. While internal metastases often remain silent until they impair organ function, skin lesions are visible and sometimes appear before deeper spread becomes apparent. Yet even though they are on the surface, they are not always immediately obvious. In many cases, early skin metastases are mistaken for benign conditions, delaying diagnosis and treatment.

Skin metastases don’t always announce themselves in the same way. They can look deceptively simple — or mimic far more common, harmless conditions. To make recognition easier, here’s a brief look at some of the most common ways they tend to show up, and what they’re often mistaken for:

| Presentation Type | Description | Common Misdiagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| Firm nodules | Small, painless lumps under the skin | Cysts, benign tumors |

| Plaques | Broad, thickened areas of skin | Scars, dermatitis |

| Infection-like redness | Warm, swollen, red patches | Cellulitis, rash |

| Blistering or ulceration | Open sores or scaling patches | Eczema, skin infections |

| Fungating wounds | Tumors breaking through skin, bleeding, fluid discharge | Severe infections, wounds |

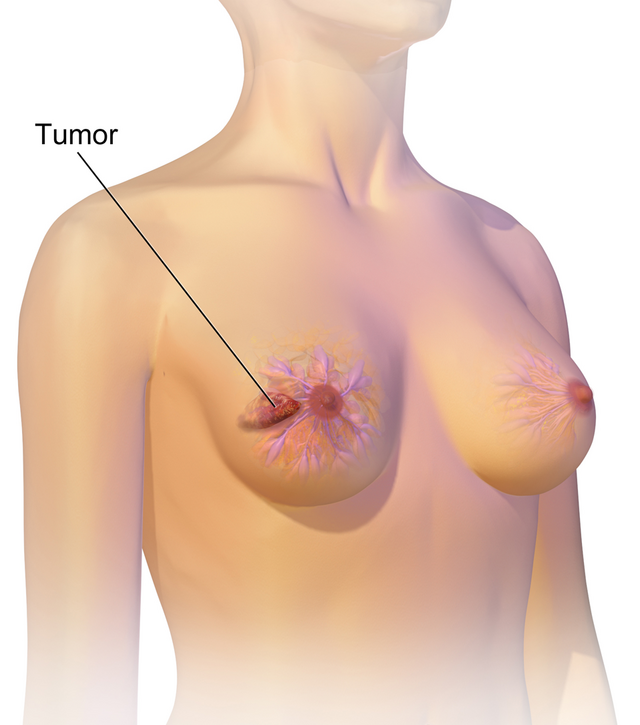

Most commonly, these metastases take the form of firm, painless nodules under the skin. They tend to arise near the site of the original breast tumor, often along the chest wall, although they can also appear across the back, abdomen, neck, or limbs. At first, the nodules may be small — no larger than a pea — and the skin above them may seem entirely normal. However, over time, they often enlarge, and subtle changes in skin color or texture can begin to emerge. Some nodules maintain the same tone as surrounding skin, while others develop a reddish, purplish, or darker appearance. In certain cases, the overlying skin becomes stretched and shiny as the underlying tumor grows.

At the same time, not all skin metastases form distinct lumps. Some present as plaques — broad, flat or slightly raised areas where the skin thickens and hardens. These plaques can easily be mistaken for scarring, dermatitis, or other inflammatory skin conditions. Even though color differences may be minor, the development of new areas of firmness or altered texture, especially near a surgical scar or radiation field, warrants careful evaluation.

In other situations, skin metastases may mimic infection. Redness, swelling, and warmth across a patch of skin often suggest cellulitis, and many patients initially receive antibiotics. However, when redness persists despite treatment, or when it spreads steadily outward, doctors must consider the possibility of cancerous infiltration. This infectious-like pattern is particularly associated with aggressive subtypes, including inflammatory breast cancer, although it can occur in others as well.

Less frequently, skin metastases may appear as small blisters, ulcerating sores, or stubborn patches that resemble eczema. Patients sometimes report scaling, flaking, or persistent weeping from affected areas. When these patches fail to improve with standard dermatological care, it raises the question of whether cancer might be involved. Open wounds that bleed easily, resist healing, or develop noticeable odor also deserve prompt medical attention.

If the disease progresses unchecked, tumors can eventually break through the skin surface, forming fungating wounds. These lesions often bleed, emit fluid, and become prone to secondary infection. Managing such wounds presents its own set of challenges, which will be addressed later. Although these are less common, their impact on physical comfort and psychological well-being can be significant.

The speed at which skin metastases develop varies greatly. In some patients, changes occur rapidly over a few weeks. In others, lesions emerge slowly over several months. It is not unusual for skin metastases to be the first sign of breast cancer recurrence, appearing even when internal imaging studies still look stable. At the same time, skin changes can also accompany known metastatic disease elsewhere.

Although not every skin abnormality in a patient with a breast cancer history will turn out to be malignant, any persistent or evolving lesion deserves thorough evaluation. Early diagnosis creates opportunities for more treatment options and better symptom control, both of which are critical for maintaining quality of life.

In the next section, we will explore how doctors move from clinical suspicion to definitive diagnosis — and why confirming the nature of a skin lesion is essential before beginning treatment.

Part 3: How Skin Metastases Are Diagnosed

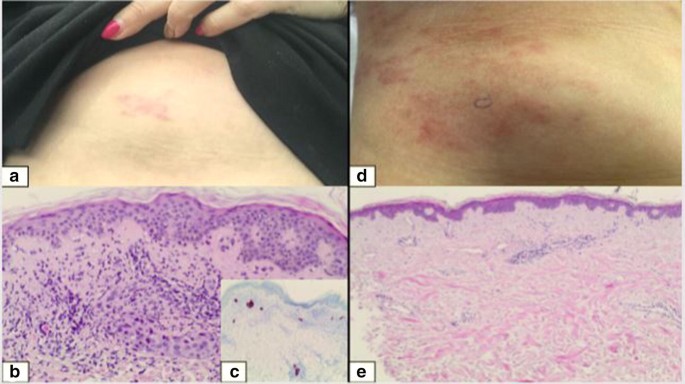

When a new skin lesion appears in a patient with a history of breast cancer, the first step is clinical evaluation. While some lesions are immediately concerning, many resemble benign skin conditions, making careful assessment essential. Physicians begin by examining the size, shape, color, and texture of the lesion, as well as its location relative to the original tumor site. They also gather information about the timing of changes and any associated symptoms such as pain, discharge, or swelling.

However, visual inspection alone cannot reliably determine whether a lesion is metastatic. Even experienced clinicians must rely on tissue analysis to make a definitive diagnosis. Patients sometimes ask whether a doctor can tell just by looking. The answer, almost always, is no. Only a biopsy can confirm whether breast cancer cells are present in the skin.

The biopsy technique depends on the lesion’s characteristics. In many cases, a punch biopsy is performed, removing a small, full-thickness cylinder of skin and underlying tissue. For nodules or isolated lumps, an excisional biopsy — complete removal of the lesion — may be preferable if technically feasible. Although these procedures are simple and quick, they are critical, because surface appearance alone often fails to reveal the extent of disease beneath.

Once a tissue sample is obtained, it is sent for pathological analysis. Under the microscope, pathologists look for cancer cells consistent with breast origin. Immunohistochemical staining is commonly used to detect hormone receptors (estrogen and progesterone) and HER2 protein. Confirming that a skin lesion shares the same receptor status as the original breast tumor helps distinguish true metastasis from unrelated skin cancers or benign conditions.

At the same time, imaging studies are usually ordered to assess the broader context. If skin metastases are present, doctors often recommend mammography or ultrasound to evaluate the breast or chest wall for local recurrence. CT scans or PET scans help determine whether the disease has spread elsewhere, while MRI provides more detailed views if soft tissue involvement is suspected. Imaging complements biopsy by mapping the overall extent of disease, which in turn shapes treatment decisions.

Understandably, many patients ask whether a blood test can detect skin metastases. The short answer is no. While blood tests can reveal general markers of inflammation or provide information about overall health, they cannot identify metastatic cells in the skin. Only biopsy can do that with certainty.

In some cases, skin metastases are the first detectable sign that breast cancer has returned or progressed. In others, they emerge alongside known internal metastases. Regardless of when they appear, prompt diagnosis allows for earlier treatment planning, symptom control, and more informed conversations about next steps.

In the following section, we will look at how treatment strategies are chosen — both to address the skin lesions themselves and to manage the underlying systemic disease.

Part 4: Treatment Options for Skin Metastases

Once breast cancer skin metastases are diagnosed, treatment planning begins. The choice of therapy depends on several factors, including the number and size of lesions, whether disease is confined to the skin or has spread elsewhere, the biological characteristics of the cancer, and the patient’s overall health and treatment history. Although the presence of skin metastases usually indicates Stage IV disease, approaches can vary significantly based on individual circumstances.

In cases where skin involvement is limited and systemic disease is absent or well-controlled, local treatments may be considered. Surgical excision of isolated skin lesions can be an option, particularly when nodules are few, accessible, and well-defined. However, even after excision, additional therapy is often recommended to address microscopic disease that might not be visible.

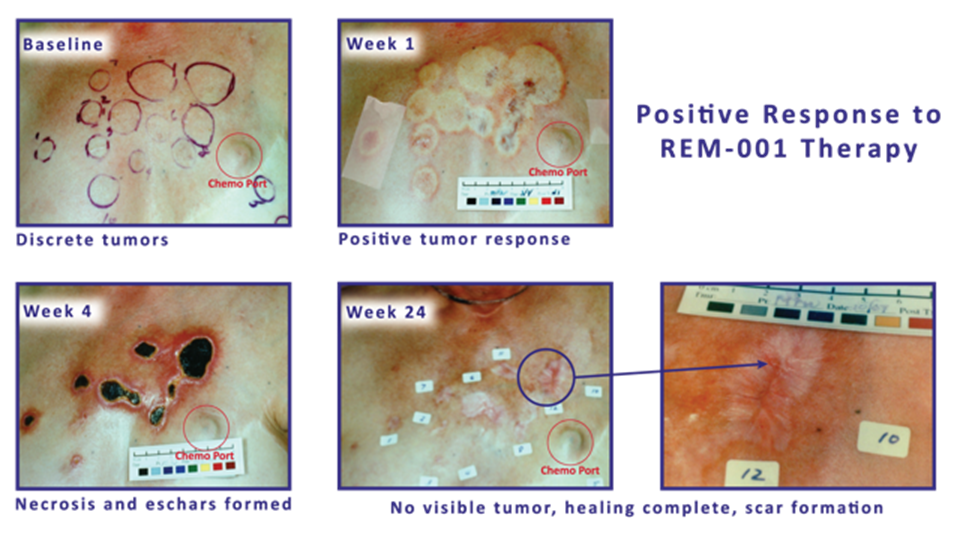

Radiation therapy represents another important tool for local control. Targeted radiation can shrink nodules, alleviate pain, reduce swelling, and sometimes close open wounds. Although radiation can cause skin irritation or fatigue, it often provides rapid symptomatic relief, especially for painful or ulcerated lesions.

In most situations, however, skin metastases are a sign of systemic disease. As a result, systemic therapy — treatment that affects the whole body — becomes the mainstay. The choice of systemic therapy is guided largely by the tumor’s receptor status.

For hormone receptor-positive cancers, endocrine therapy (such as aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen, or CDK4/6 inhibitors) remains the backbone of treatment. When the cancer expresses HER2 protein, targeted therapies like trastuzumab or newer antibody-drug conjugates may be used. For triple-negative breast cancers, which lack hormone receptors and HER2, chemotherapy remains the primary option, although immunotherapy is increasingly available in selected cases, especially when PD-L1 expression is detected.

At the same time, systemic therapy often serves not only to control internal disease but also to shrink or stabilize skin lesions. A good systemic response can lead to flattening of nodules, resolution of plaques, and in some cases, complete clearance of visible skin disease. However, skin metastases are sometimes more resistant to treatment than internal lesions, requiring adjustments in therapy over time.

Palliative treatments also play a crucial role when skin lesions cause discomfort, infection, or bleeding. Specialized wound care teams help manage fungating wounds, using dressings that minimize pain, control odor, and protect fragile tissues. Pain management, often combining topical and systemic medications, helps maintain quality of life even when curative treatment is no longer possible.

In some cases, when standard treatments are no longer effective or when disease progresses rapidly, patients may be offered participation in clinical trials. These studies investigate new drugs, drug combinations, or novel therapeutic approaches. While not all clinical trials are appropriate for every patient, they represent an important option for those seeking additional lines of therapy.

Treatment planning is always individualized. No single approach fits every patient, and goals can shift over time — from trying to control disease progression to focusing primarily on comfort and symptom relief. Honest discussions between patients and their care teams are essential for aligning medical recommendations with personal values and priorities.

In the next section, we will examine how doctors and patients monitor disease activity after treatment begins — and what signs may suggest that therapy needs to be adjusted.

Part 5: Monitoring Progress and Recognizing New Changes

Once treatment for skin metastases begins, regular monitoring becomes essential. The goal is twofold: to assess how well the therapy is controlling the visible lesions and to detect any signs of disease progression as early as possible. Monitoring combines medical evaluations, imaging studies, and patient self-observation, forming a continuous feedback loop that shapes treatment decisions.

At home, it helps to have a clear sense of what changes deserve closer attention. While not every new spot or discomfort signals progression, certain signs should always prompt a call to the care team. Some of the key ones include:

- Appearance of new nodules, plaques, or patches

- Growth or change in existing lesions

- Development of skin ulceration, bleeding, or persistent wounds

- New localized pain, swelling, or warmth

- Persistent or worsening symptoms despite treatment

During follow-up visits, physicians carefully examine the skin, checking whether treated nodules have shrunk, whether plaques have softened, and whether open wounds are healing. Even small changes in color, size, or texture provide important clues about how the disease is responding. Although complete resolution of skin lesions is possible in some cases, stabilization without further growth is also considered a favorable outcome.

At the same time, systemic monitoring is important. Imaging studies — such as CT scans, PET scans, or MRIs — are performed periodically to evaluate internal disease status. Blood work may also be ordered to check organ function, although, as noted earlier, blood tests cannot specifically monitor skin lesions. When imaging shows stability and skin lesions are improving or stable, treatment typically continues. If new findings emerge, adjustments may be needed.

Patients themselves play a critical role in day-to-day monitoring. Many changes first become apparent not during office visits, but at home. Recognizing which signs warrant prompt medical attention is an important part of living with metastatic disease.

Key signs that may indicate a need for treatment reassessment include:

- New skin lesions

The sudden appearance of new nodules, plaques, or patches elsewhere on the body may suggest that current therapy is no longer fully controlling disease spread. New lesions require evaluation, and often, biopsy confirmation if the diagnosis is uncertain.

- Growth of existing lesions

Even with treatment, some lesions may enlarge or change in character. A nodule that becomes larger, firmer, or more painful over a short period may indicate resistance to therapy. Progressive growth often triggers a reassessment of systemic therapy effectiveness.

- Development of ulceration or open wounds

Skin that breaks down, bleeds, or exudes fluid despite treatment suggests aggressive local behavior. New or worsening wounds are not only a quality-of-life concern but also a risk for infection, requiring immediate attention from wound care specialists.

- New symptoms such as pain, warmth, or swelling

Localized pain, increasing warmth, or new swelling near treated sites can sometimes signal recurrence or infection. While some discomfort is expected with healing tissues, persistent or worsening symptoms merit clinical evaluation.

Not every change signals failure of treatment. Some skin changes, such as temporary redness or flaking, may result from healing processes or treatment side effects rather than disease progression. Still, in the setting of metastatic breast cancer, caution is appropriate. Patients are encouraged to report new findings promptly rather than waiting for scheduled appointments.

Doctors evaluate the broader clinical picture when deciding whether therapy should continue, be modified, or be changed entirely. Stability, partial response, or continued regression of skin lesions generally supports continuing current treatment. On the other hand, evidence of active progression — particularly if combined with new internal metastases — usually prompts a change in therapeutic strategy.

In the next section, we will examine how treatment strategies shift when skin metastases continue to grow despite initial therapy — and what options remain when first-line treatments are no longer effective.

Part 6: When Skin Metastases Progress Despite Treatment

Even with carefully chosen therapies, breast cancer skin metastases do not always respond as hoped. In some cases, lesions continue to grow, new areas of involvement appear, or symptoms worsen despite active treatment. Progression does not mean that all options are exhausted, but it does signal the need to reassess the therapeutic approach.

Often, the first signs of progression appear at the skin level: new nodules form, plaques expand, or existing wounds worsen. Sometimes systemic imaging reveals simultaneous internal progression, while in other cases the skin changes occur in isolation. Regardless of how progression is detected, the next steps depend on several factors, including prior treatments, overall disease burden, and the patient’s condition and goals.

When skin metastases progress, doctors typically consider several strategies:

- Changing systemic therapy

When a cancer stops responding to one line of systemic treatment, switching to a different regimen becomes necessary. This might involve moving from one class of endocrine therapy to another, introducing chemotherapy, or changing targeted therapy if the cancer expresses markers like HER2. In triple-negative cases, chemotherapy regimens may be adjusted, or immunotherapy may be introduced if appropriate. Changing systemic treatment aims not only to control internal disease but also to limit further skin involvement.

- Adding or adjusting local treatments

Even if systemic therapy is modified, localized interventions may help manage particularly troublesome skin lesions. Radiation therapy can shrink painful or ulcerated nodules, reducing discomfort and risk of infection. In selected cases, surgical excision of isolated progressing lesions may still be considered, although this is usually reserved for lesions that cause significant symptoms or functional impairment.

- Considering clinical trials

For patients whose disease resists standard treatments, participation in clinical trials offers access to investigational therapies. These may include new targeted drugs, novel immunotherapies, or innovative drug combinations not yet widely available. Although clinical trials are not suitable for every patient, they provide an important opportunity for those who have exhausted conventional options.

- Prioritizing palliative and supportive care

When disease progression becomes difficult to control, the focus may shift increasingly toward symptom management. Specialized wound care teams can address fungating wounds, using advanced dressings to minimize pain, bleeding, and odor. Pain specialists can help optimize analgesia without excessive side effects. Psychological support becomes even more critical, helping patients and families navigate the emotional landscape of advanced illness.

It is important to recognize that changing treatments after progression is not an admission of defeat. Cancer biology is dynamic, and therapies must adapt accordingly. Many patients experience multiple lines of treatment over the course of living with metastatic disease, adjusting the strategy as needed based on disease behavior and personal goals.

Decisions about next steps should be made collaboratively, with open discussions about what each option offers, what it demands, and what outcomes are realistically possible. Maintaining quality of life remains a priority, even when cure is no longer achievable. In many cases, thoughtful shifts in treatment can still lead to meaningful periods of stability, comfort, and connection.

In the next section, we will focus on how symptom management and supportive care help maintain dignity and well-being throughout the course of treatment.

Part 7: Managing Symptoms and Supporting Quality of Life

Living with skin metastases from breast cancer brings challenges that go beyond managing the cancer itself. As the disease affects the skin — often a highly visible and sensitive part of the body — it introduces new physical and emotional burdens that must be addressed with as much care as the tumor itself. Managing these symptoms is not an afterthought. It is an essential part of maintaining dignity, comfort, and personal strength throughout treatment.

One of the most immediate concerns for many patients is pain. Although some skin lesions remain painless, others can become sources of constant discomfort. Pain might arise from pressure exerted by growing nodules, from inflammation in surrounding tissues, or from open wounds where the skin has broken down. Addressing this pain is often a first step in supportive care, using a combination of systemic medications and localized treatments. Doctors may prescribe oral analgesics based on the severity of symptoms, while topical anesthetics like lidocaine gels can help numb particularly tender areas, making day-to-day activities less distressing.

As treatment progresses, managing the integrity of the skin itself becomes equally important. Skin affected by metastases is often fragile, vulnerable to cracking, bleeding, or ulceration. When lesions open into wounds — a process sometimes seen in more advanced or neglected cases — specialized wound care is essential. These wounds, often referred to as fungating lesions, are prone to bleeding, infection, and unpleasant odors. They require a thoughtful approach, using gentle dressings that protect the skin while minimizing trauma during dressing changes. Wound care teams also prioritize odor control, using products like charcoal dressings or antimicrobial creams to help patients maintain comfort and social confidence.

With any breach of the skin’s natural barrier, the risk of infection rises sharply. Even a small open area can serve as an entry point for bacteria, and infections can escalate quickly in tissues already compromised by cancer. Recognizing the early signs of infection — increased redness, warmth, discharge, or systemic symptoms like fever — allows for prompt treatment. In many cases, infections can be managed with targeted antibiotics, often guided by culture tests to ensure the right drug is chosen.

Sometimes, the physical complications extend beyond the skin itself. Breast cancer that spreads into the lymphatic system can obstruct normal fluid drainage, leading to a condition called lymphedema. Swelling, often affecting the chest, arm, or back, can create additional discomfort and limit mobility. Managing lymphedema requires a combination of therapies: physical therapy to encourage lymphatic drainage, compression garments to reduce swelling, and sometimes more specialized interventions like manual lymphatic massage. Left untreated, lymphedema can exacerbate the vulnerability of the skin, creating a cycle of swelling, skin breakdown, and increased infection risk.

Yet the challenges of skin metastases are not purely physical. Visible changes to the skin can have profound emotional effects. For many patients, the skin is not just a protective barrier but a central part of their sense of self. Changes that are disfiguring, difficult to hide, or associated with odors and bleeding can cause deep distress, eroding confidence and leading to social withdrawal. Depression, anxiety, and feelings of isolation are common, and they deserve the same level of clinical attention as the cancer itself.

To address these emotional needs, psychosocial support is critical. Many oncology teams include counselors or psycho-oncologists trained to help patients navigate the emotional terrain of advanced cancer. Talking openly about body image concerns, fears of judgment, and grief over physical changes can help reclaim a sense of agency and resilience. In addition to professional support, peer groups — whether in person or online — offer unique comfort. Sharing experiences with others who understand firsthand the realities of living with visible metastases can ease loneliness and offer practical strategies for coping day to day.

Throughout all stages of managing skin metastases, the focus remains steady: preserving not just life, but the quality of that life. Effective symptom management, compassionate emotional support, and a holistic understanding of each patient’s goals create a foundation where hope, dignity, and strength can endure, even in the face of serious illness.

In the next part, we’ll explore what skin metastases usually mean for long-term outlook, and why each person’s journey remains uniquely their own.

Part 8: Prognosis and Long-Term Outlook

When breast cancer spreads to the skin, many patients understandably ask: What does this mean for my future?

There is no single answer. Skin metastases usually indicate that breast cancer has reached Stage IV, or metastatic status. However, outcomes vary depending on the biology of the cancer, how widespread the disease is, how well it responds to treatment, and the patient’s overall condition.

For some patients, skin metastases are one part of a broader pattern of metastasis, involving internal organs such as the liver, lungs, or bones. In these cases, skin involvement often reflects a more aggressive disease course, and prognosis tends to align with the typical survival patterns seen in metastatic breast cancer overall. Historically, median survival has ranged from months to several years. However, advances in treatment mean that many people today live longer than past averages would predict, managing the disease over several years with successive therapies.

In other cases, skin metastases may be more limited. Some patients develop only isolated lesions, with slower progression and minimal spread to other organs. When systemic therapies control the disease effectively, quality of life can remain good for extended periods. While these cases are less common, they do occur.

The subtype of breast cancer plays a major role in prognosis. Hormone receptor-positive cancers generally have more treatment options and better overall survival statistics. HER2-positive cancers, once associated with poorer outcomes, now often respond well to targeted therapies. Triple-negative breast cancers remain more difficult to treat, particularly when metastatic, although immunotherapy and new drug combinations are offering more options than in the past.

Patients sometimes wonder whether skin metastases themselves are fatal. In most cases, they are not the immediate cause of life-threatening complications. However, untreated skin lesions can become a source of infection, bleeding, or significant pain, all of which can severely affect quality of life and overall health.

Doctors monitor disease status through physical examinations, imaging studies, and symptom reviews. Stability — meaning that skin lesions are not growing, spreading, or causing serious complications — is considered a positive sign. New lesions, rapid changes, or worsening systemic symptoms typically prompt a reassessment of the treatment plan.

Although average survival statistics provide general guidance, each patient’s course is individual. Advances in systemic therapies, clinical trials, and supportive care mean that outcomes are often better than they were even a few years ago.

Quality of life remains an important part of prognosis discussions. Survival length matters, but so does the ability to live comfortably, maintain independence, and stay connected to daily activities and relationships. Treatment decisions should always balance disease control with personal values and goals.

In the next part, we will focus on practical strategies for living with skin metastases and maintaining daily routines despite the challenges.

Part 9: Practical Living with Skin Metastases

Managing breast cancer skin metastases is not only about medical treatment. It also requires daily adjustments in how patients care for their skin, monitor their bodies, handle symptoms, and navigate the psychological impact of living with visible disease. Many patients ask: What can I do at home to stay as healthy and comfortable as possible? The answer involves practical, consistent routines, guided by medical advice but adapted to real life.

One of the most important areas of day-to-day management is skin care. Because skin affected by metastases is often thinner, more fragile, or more prone to breakdown, it requires careful handling. Gentle washing with mild, fragrance-free cleansers helps prevent irritation. Patting the skin dry rather than rubbing it can reduce the risk of injury. Moisturizers recommended by the healthcare team can help maintain skin integrity without clogging pores or irritating lesions.

Protecting skin from trauma is another important step. Clothing made from soft, breathable fabrics can minimize friction over affected areas. In cases where lesions are exposed or easily irritated, non-stick dressings may be recommended to prevent direct contact with clothing. Patients should avoid adhesive bandages unless specifically directed by their care team, as removing sticky dressings can damage fragile skin.

Monitoring for new changes remains an ongoing task. Patients are often encouraged to perform regular self-examinations, noting any new nodules, color changes, warmth, discharge, or signs of infection. Having a baseline understanding of what the skin normally looks and feels like can make it easier to detect subtle changes early. However, patients should not feel they are solely responsible for assessment. Regular medical appointments remain essential for professional evaluation.

Pain management at home is an evolving process. Some patients find that scheduled pain medication, rather than taking it only when symptoms become severe, provides better control. Others use topical treatments alongside systemic medications to target specific tender areas. Communication with the medical team is key, particularly if pain worsens or if side effects from pain medications interfere with daily activities.

Dealing with fatigue is another common concern. Fatigue in metastatic breast cancer is often both physical and emotional. Balancing rest with gentle activity, such as short walks or light stretching, can sometimes help manage energy levels. Patients are often advised to prioritize tasks that are most meaningful to them and to allow themselves flexibility without guilt when energy is low.

The psychological impact of skin metastases can be harder to predict and even harder to manage. Some patients adapt quickly to visible changes, while others struggle with self-consciousness, grief, or anxiety. Open conversations with trusted friends, family members, or counselors can ease the emotional burden. In some cases, patients choose to join support groups focused specifically on living with metastatic breast cancer, where experiences are shared without judgment.

Finally, planning for practical needs can ease daily life. For example, arranging medical supplies for dressing changes ahead of time, planning gentle activities during periods of higher fatigue, or scheduling treatments to allow recovery days can all make a difference. Patients may also benefit from early conversations with social workers or case managers about financial assistance, transportation services, and home healthcare options if needed.

Living with skin metastases changes daily routines, but it does not erase the ability to live meaningfully. Small adaptations, consistent monitoring, open communication, and support — both medical and personal — form the foundation of practical, sustainable living with this condition.

In the next and final section, we will summarize key points and reflect on how patients, families, and care teams can work together to maintain strength and hope across all stages of this journey.

Part 11: FAQs About Breast Cancer Skin Metastases

Can skin metastases be mistaken for infections?

Yes. Skin metastases often mimic infections like cellulitis. Patients and doctors may first think the redness and swelling are caused by bacteria. Antibiotics are sometimes prescribed, but when the redness does not improve — or keeps spreading — doctors start to suspect cancer. A biopsy usually confirms the difference. Whenever skin changes near a previous breast cancer site don’t respond to normal infection treatment, further evaluation is needed.

Are skin metastases always a sign of widespread disease?

Not always, but often. In some cases, skin metastases are the first and only sign of cancer spread. In others, they appear alongside internal metastases in the bones, liver, lungs, or brain. Even when skin metastases are the only visible sign, staging scans are important to check for hidden disease. Skin involvement places breast cancer into Stage IV, but the overall burden of disease can vary widely.

Do skin lesions hurt?

Sometimes. Early nodules and plaques are often painless. As lesions grow or ulcerate, they can become tender, sore, or itchy. If infection sets in, pain usually worsens. Pain levels vary from person to person. Doctors work closely with patients to manage discomfort, using medications, wound care techniques, and other supportive measures.

Can skin metastases heal or disappear with treatment?

They can. When systemic treatments like chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or targeted therapy work well, skin lesions may shrink, flatten, and sometimes disappear completely. Radiation therapy can also help clear localized skin disease. However, even when visible lesions heal, doctors continue close monitoring, as microscopic disease may persist beneath the surface.

How are fungating breast cancer wounds managed?

Fungating wounds require specialized care. Wound care nurses use dressings that absorb drainage, reduce odor, and protect fragile tissue. Pain management is crucial, both at dressing changes and throughout daily life. Antibiotics may be needed if infection sets in. Good wound care can dramatically improve comfort, dignity, and quality of life, even when the wounds cannot be fully closed.

Can imaging detect all skin metastases?

No. Imaging like CT or PET scans can detect deeper tumors and some skin involvement, but small or early skin metastases often do not show up well on scans. Physical examination and biopsy remain the best ways to diagnose skin lesions. Imaging is more useful for checking internal spread beyond the skin.

What should patients look for when monitoring treated skin areas?

Patients should watch for new lumps, patches, or plaques near previous cancer sites. They should also monitor existing lesions for changes in size, color, pain, or surface breakdown. New warmth, tenderness, or fluid drainage should be reported promptly. Even small changes can carry important information about how the disease is behaving.

Part 10: Final Thoughts and Summary

Breast cancer that spreads to the skin presents challenges that are both visible and deeply personal. It marks a progression of disease that requires thorough medical attention, but it also demands patience, adaptation, and resilience from those living with it.

Throughout this guide, we have looked closely at what skin metastases are, how they appear, how they are diagnosed, and how they are treated. We have discussed the practical realities of managing symptoms, monitoring for changes, and maintaining quality of life despite the ongoing presence of disease. Each step reflects a simple truth: even when cancer becomes more complex, care must remain comprehensive — addressing not only tumors, but the individual living with them.

There are several key points to carry forward. First, skin metastases signal metastatic breast cancer, but their appearance and impact vary widely. Some cases are aggressive, while others remain localized and manageable for long periods. Second, early recognition and confirmation through biopsy are essential for proper treatment planning. Third, therapies — whether local, systemic, or palliative — must be chosen based not only on medical factors but also on the patient’s goals and preferences.

Living with skin metastases often means learning to monitor the body in new ways, adapting daily routines, and finding ways to navigate visible changes. It requires consistent communication with healthcare providers, openness to adjusting treatments, and attention to both physical and emotional needs. Support systems, whether professional or personal, are critical. No one should have to navigate this path alone.

Throughout treatment and beyond, questions will arise: What is changing? What options remain? How can life remain as full and meaningful as possible? These are questions that deserve honest answers and thoughtful guidance, grounded in up-to-date knowledge and real-world experience.

While skin metastases are a serious development, they do not erase hope. Advances in therapy continue to expand the possibilities for longer survival and better quality of life. Even in the presence of visible disease, patients can find strength, purpose, and connection.

The work of living with metastatic cancer is ongoing. It is shaped by moments of uncertainty, but also by resilience, by informed decisions, and by the unwavering effort to maintain dignity and agency. Medical teams, family, and communities all play a role in supporting that effort.

No two experiences with skin metastases are identical. Yet every person facing this challenge deserves the same foundation: clear information, compassionate care, and the recognition that they are more than their diagnosis.