Understanding Brain Cancer in Cats: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Care

- What Is Brain Cancer in Cats?

- Types of Brain Tumors Found in Cats

- Early Warning Signs and Behavioral Changes

- Physical Symptoms Beyond Behavior

- Diagnostic Process: From Symptoms to Imaging

- Treatment Options: Surgery, Radiation, and Medication

- Prognosis and Life Expectancy

- Differentiating Brain Cancer From Other Illnesses

- The Emotional and Behavioral Toll on Pet Owners

- Comparing Brain and Bone Cancer in Felines

- Table of Common Symptoms and Their Clinical Significance

- Supportive and Hospice Care at Home

- Nutritional Considerations During Illness

- The Role of Genetics and Breed Susceptibility

- Monitoring Disease Progression Over Time

- Euthanasia Decisions and Owner Guidance

- FAQ

What Is Brain Cancer in Cats?

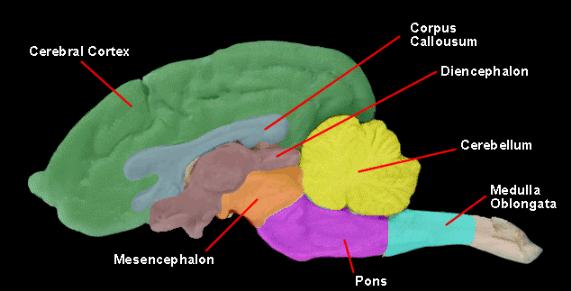

Brain cancer in cats refers to the presence of a malignant tumor within the cranial cavity. These tumors can originate in the brain itself (primary) or spread from other parts of the body (secondary or metastatic). The most common primary brain tumors in felines are meningiomas, which arise from the membranes covering the brain, and gliomas, which form in the brain tissue.

Because the brain controls virtually every bodily function, even small tumors can cause significant neurological symptoms. Brain tumors can grow slowly or rapidly depending on their type and aggressiveness, and they often go unnoticed until they interfere with behavior or motor skills.

Understanding the nature of these tumors helps pet owners grasp why symptoms can vary so widely and why treatment options need to be tailored to the tumor’s type, location, and progression.

Types of Brain Tumors Found in Cats

Veterinary neurologists typically classify brain tumors in cats into several categories based on origin, cellular makeup, and location. Primary brain tumors originate in the brain and include:

- Meningiomas: The most common, often slow-growing and sometimes surgically removable.

- Gliomas: Aggressive tumors arising from glial cells; prognosis is often guarded.

- Choroid plexus tumors: Rare but significant, often affecting cerebrospinal fluid dynamics.

Secondary tumors, such as lymphomas or metastatic cancers from other body parts, can also affect the brain. These tumors often present more diffusely and may not be operable, though they sometimes respond to chemotherapy or radiation.

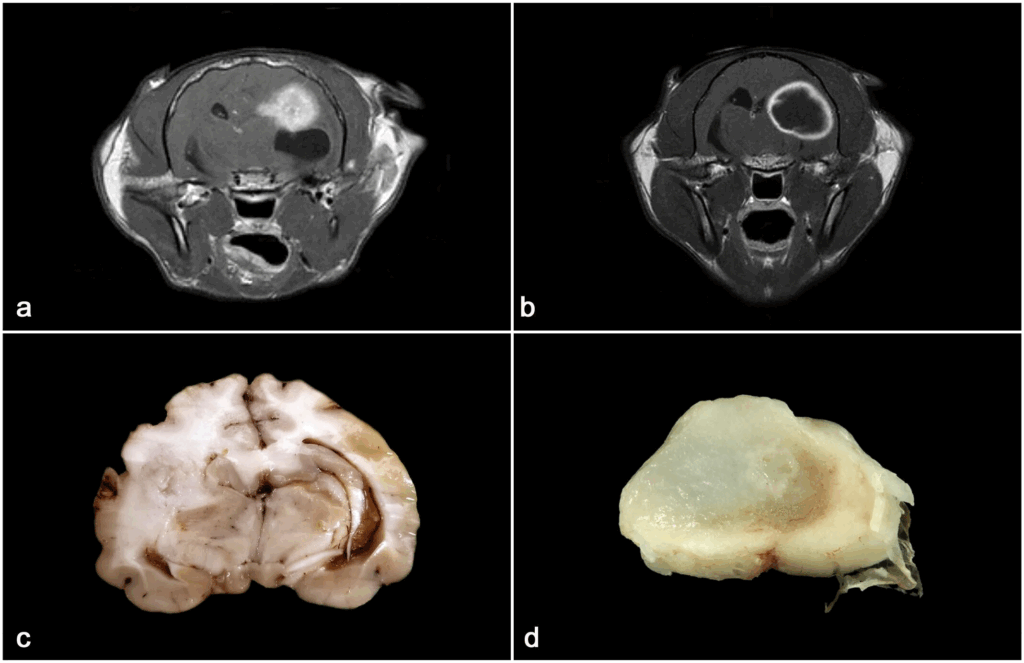

Advanced imaging techniques like MRI are often required to differentiate between these types and determine the best treatment strategy.

Early Warning Signs and Behavioral Changes

The first indicators of brain cancer in cats often involve subtle shifts in personality or behavior. A previously playful or affectionate cat might become withdrawn, disoriented, or aggressive. Loss of learned behaviors, such as litter box use or basic responsiveness, is also common.

More overt symptoms include head pressing (a sign of increased intracranial pressure), circling, vision loss, or uncoordinated movements. These signs are often misattributed to aging or other neurological conditions, leading to delayed diagnosis.

Recognizing these changes early can prompt veterinary evaluation before the tumor progresses to an untreatable stage. Behavioral abnormalities should never be dismissed, especially when they appear suddenly or worsen over time.

Physical Symptoms Beyond Behavior

In addition to changes in personality, cats with brain cancer may experience physical signs such as seizures, which are the most recognizable neurological red flag. These seizures may range from subtle facial twitching to full-body convulsions and often increase in frequency or intensity as the tumor grows.

Other symptoms may include head tilt, uneven pupil sizes, difficulty walking, or weakness on one side of the body. Because these signs may mimic conditions like ear infections or stroke, veterinary professionals must rule out other causes.

In rare cases, a cat may display signs like excessive vocalization, which can stem from disorientation or discomfort. These symptoms often become more pronounced as intracranial pressure increases.

Diagnostic Process: From Symptoms to Imaging

Diagnosing brain cancer in cats begins with a thorough neurological examination to assess reflexes, balance, vision, and cranial nerve function. Vets use these findings to localize the affected area of the brain and determine whether advanced testing is needed.

Standard bloodwork and urinalysis are typically performed to rule out systemic illnesses or infections that could mimic neurological disease. However, a definitive diagnosis usually requires imaging. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is considered the gold standard due to its ability to detect soft-tissue changes with high detail. CT scans may also be used when MRI is unavailable.

In some cases, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis can provide additional information, especially when lymphoma is suspected. A biopsy, while rare due to surgical risk, may be performed when identifying tumor type is critical for treatment decisions.

Treatment Options: Surgery, Radiation, and Medication

Treatment plans for feline brain cancer depend on the tumor’s type, location, and stage. Meningiomas, which are often encapsulated, can sometimes be surgically removed with promising outcomes. However, surgery is rarely curative for gliomas or metastatic tumors.

Radiation therapy is frequently used to reduce tumor size and control symptoms, especially for inoperable or partially resected masses. While this treatment may not offer a cure, it can significantly extend quality of life. Chemotherapy is less commonly used but may be an option in certain lymphomas or systemic cancers involving the brain.

Palliative medications such as corticosteroids can help manage brain swelling, while anticonvulsants may be prescribed for seizure control. These drugs do not treat the tumor itself but can offer meaningful relief from symptoms.

Prognosis and Life Expectancy

Prognosis for brain cancer in cats is highly variable. Cats with surgically removable meningiomas may live one to two years or longer post-surgery, especially when combined with radiation. In contrast, those with aggressive or multifocal tumors may survive only a few weeks to months, even with supportive care.

The presence of seizures, rapid tumor growth, and metastasis to other organs generally worsens the outlook. Early diagnosis and timely intervention significantly influence long-term survival and quality of life.

For many pet owners, understanding prognosis helps guide emotionally difficult decisions about treatment intensity and end-of-life care. Quality of life should remain the central consideration throughout the disease course.

Differentiating Brain Cancer From Other Illnesses

Many feline health issues can cause neurological signs similar to those of brain cancer. Vestibular disease, liver shunts, toxoplasmosis, and hypertensive encephalopathy are just a few conditions that may initially look like a brain tumor.

Moreover, some symptoms—such as vocalizing, disorientation, or changes in gut behavior—can confuse owners. For example, excessive gastrointestinal sounds in cats with disorientation may resemble issues described in humans with bowel cancer stomach noises — вставить ссылку на статью про bowel cancer stomach noises — though in felines this is more likely due to neurologic control loss or anxiety.

Proper diagnosis is essential to avoid mistreatment or delays in appropriate care. Veterinarians use differential diagnosis and clinical experience to distinguish between these conditions and narrow down the cause of neurological signs.

The Emotional and Behavioral Toll on Pet Owners

Caring for a cat with brain cancer is emotionally draining and often accompanied by uncertainty, guilt, and grief. Pet owners may struggle to interpret their cat’s discomfort or decide whether treatment is in the animal’s best interest. It’s common to feel conflicted between extending life and preserving quality of life.

Veterinarians can offer guidance by explaining how symptoms are likely to progress and what behaviors may indicate suffering. Some owners benefit from creating a “quality-of-life scale” to track appetite, mobility, interaction, and comfort over time. Support groups, whether online or in-person, also help pet guardians process emotions and make informed choices.

Understanding that brain cancer is not a reflection of inadequate care but rather a medical reality can ease self-blame. Compassionate veterinary teams can walk alongside families during decision-making and palliative care stages.

Comparing Brain and Bone Cancer in Felines

Cats can experience several types of cancer simultaneously or consecutively, making it important to differentiate between neurological and skeletal cancers. While brain cancer often presents with seizures and balance issues, bone cancer in cats usually involves visible swelling, pain when walking, or limping.

These two cancer types share some common mechanisms, such as aggressive cell replication and the potential for metastasis, but their treatment and prognosis vary widely. For example, bone tumors may be detected on radiographs, while brain tumors often require advanced imaging like MRI. In some rare cases, cancer may metastasize from bone to brain or vice versa, although this is uncommon in felines.

Learn more about how bone cancer in cats affects mobility, pain levels, and treatment approaches — вставить ссылку на статью про bone cancer in cats — to understand how symptom profiles differ and intersect.

Table of Common Symptoms and Their Clinical Significance

The following table outlines major symptoms seen in cats with brain cancer, their potential underlying causes, and what they might indicate in a clinical context:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Clinical Implication |

| Seizures | Tumor disrupting electrical signals | Neurological emergency; often progressive |

| Head pressing | Increased intracranial pressure | Sign of discomfort or disorientation |

| Circling behavior | Lesion in one cerebral hemisphere | Possible mid-brain involvement |

| Loss of vision | Optic nerve compression | Advanced tumor growth |

| Vocalization | Confusion or discomfort | May reflect pain or anxiety |

| Appetite loss | Brain-gut disruption | Nutritional concern; quality of life marker |

| Weakness in limbs | Tumor compressing motor regions | Indicates worsening neurologic function |

This chart helps cat owners identify patterns and communicate them clearly to veterinarians, ensuring early intervention and informed treatment decisions.

Supportive and Hospice Care at Home

When curative treatment is not an option or has failed, hospice care becomes essential. The goal of palliative care is not to extend life at all costs but to ensure the cat is as comfortable and pain-free as possible in its remaining time.

Hospice care may include medications to reduce brain swelling and control seizures, soft bedding, assistance with grooming, and environmental adjustments to prevent injury from disorientation. A quiet space, consistent routine, and gentle interaction can reduce stress for the cat and strengthen the human-animal bond during this vulnerable period.

Some cats can live several months with appropriate supportive care, especially when symptoms are managed well. Regular veterinary check-ins help assess changes and guide humane decisions when the time for euthanasia approaches.

Nutritional Considerations During Illness

As a cat with brain cancer progresses through illness, its ability to maintain regular eating habits often becomes compromised. Neurological dysfunction can affect coordination, making it difficult for the cat to find or consume food. In other cases, the tumor may interfere with the hypothalamus or other brain regions involved in appetite regulation, leading to reduced interest in food altogether.

This creates a nutritional challenge: how to provide sufficient calories and nutrients in a format that’s accessible and appealing. Wet food, especially varieties that are high in protein and rich in scent, may help entice reluctant eaters. Hand-feeding, warming the food slightly, or adding flavor enhancers like tuna water or bone broth can further stimulate appetite. For more severe cases, veterinary diets formulated for critical care (such as high-calorie paste or mousse) may be required.

In cats that stop eating entirely, assisted feeding through syringes or feeding tubes becomes an ethical and medical decision. Maintaining hydration is equally important. Tumor-affected cats often forget to drink or may be unable to approach their water source safely. This can be managed with subcutaneous fluids or fluid-enriched diets.

The Role of Genetics and Breed Susceptibility

Although research on feline brain tumors is still developing, certain genetic and breed-related patterns have begun to emerge. Studies indicate that brachycephalic breeds, such as Persians and Himalayans, have a higher incidence of intracranial meningiomas. These tumors originate from the meninges—the protective membranes covering the brain—and are generally benign but space-occupying.

While a clear-cut genetic mutation has not yet been identified in cats as it has in some human brain cancers, familial predisposition cannot be ruled out. Additionally, cats with compromised DNA repair mechanisms—possibly due to inherited traits—may be more prone to neoplastic transformation.

Understanding potential breed susceptibility can guide earlier screening. For example, in older Persian cats that begin displaying even subtle signs of confusion or gait disturbance, early referral for neurologic assessment can lead to faster diagnosis and better management options. Despite this, brain cancer can affect any cat, and environmental triggers or spontaneous mutations are often just as important as genetics.

Monitoring Disease Progression Over Time

Tracking the clinical course of feline brain cancer requires attentiveness and coordination between pet owners and veterinary teams. Neurologic symptoms can evolve gradually or escalate rapidly depending on tumor type and location. Documenting changes on a daily basis—such as frequency of seizures, coordination changes, or behavioral shifts—can be crucial for adjusting medications and treatment plans.

Veterinarians often use quality-of-life scales to help families quantify changes in appetite, hydration, hygiene, pain, and interaction. Objective measures like gait scoring, pupil response tests, or follow-up MRIs provide visual confirmation of tumor stability or progression. In cases of corticosteroid treatment, owners must also monitor for side effects like increased thirst, urination, or muscle wasting, which may influence care decisions.

A stable cat with a slow-growing tumor may live comfortably for months or even years. Conversely, sudden deterioration—such as complete collapse, unresponsiveness, or severe cluster seizures—may indicate a critical threshold has been crossed, prompting immediate reevaluation of goals.

Euthanasia Decisions and Owner Guidance

The decision to pursue euthanasia in a cat with brain cancer is deeply personal and emotionally difficult. It requires balancing medical facts, ethical considerations, and the cat’s current quality of life. While some cats with tumors like meningiomas may remain comfortable for extended periods, others may suffer rapid neurological decline that leaves little room for meaningful recovery.

Owners may struggle with the uncertainty of timing. A helpful rule is to watch for cumulative signs of suffering—persistent seizures despite medication, inability to eat or drink, withdrawal from social contact, or continuous anxiety and restlessness. These are red flags that the disease has reached a stage where comfort can no longer be reliably preserved.

Veterinarians often recommend using structured quality-of-life checklists, such as the HHHHHMM Scale (Hurt, Hunger, Hydration, Hygiene, Happiness, Mobility, More good days than bad). These tools can provide clarity at a time when emotions are overwhelming.

Some pet owners draw insight from parallel cases in other species. For example, bone cancer in dogs life expectancy without treatment often leads to similar end-of-life decisions when pain or immobility becomes unmanageable — вставить ссылку на статью bone cancer in dogs life expectancy without treatment. Regardless of species, the goal is the same: to ensure dignity, peace, and relief from suffering.

FAQ

What are the first signs of brain cancer in cats?

The earliest signs are often subtle behavioral changes—such as increased aggression, withdrawal, or confusion. Cats may begin to miss the litter box, avoid affection, or pace aimlessly. Over time, symptoms like head pressing, circling, or seizures may develop as the tumor progresses.

Can brain tumors in cats be cured?

Curability depends on the type and location of the tumor. Some tumors, like meningiomas, may be surgically removed and followed by radiation therapy to extend survival. However, aggressive tumors or those in inoperable areas are typically managed rather than cured.

How are brain tumors diagnosed in cats?

Diagnosis usually begins with a neurological exam and bloodwork to rule out other causes. MRI is the gold standard for visualizing the brain. In some cases, a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tap may help detect certain types like lymphoma. Biopsies are rare due to surgical risk.

Do brain tumors cause pain in cats?

While the brain itself has no pain receptors, tumors can cause pain indirectly by increasing pressure inside the skull or affecting nerves. Cats may show signs of discomfort like restlessness, vocalization, or head pressing, which suggest the need for palliative support.

Are older cats more at risk for brain cancer?

Yes, most feline brain tumors occur in cats over 10 years of age. Aging cells are more prone to mutation, and the immune system becomes less efficient at detecting abnormal growths. However, younger cats are not immune and should be evaluated if symptoms arise.

What types of brain tumors are most common in cats?

Meningiomas are the most frequently diagnosed and are often benign but space-occupying. Gliomas, choroid plexus tumors, and metastatic cancers from other organs are less common but usually more aggressive. Each type requires a different treatment strategy.

Can seizures be controlled in cats with brain cancer?

Yes, anticonvulsant medications like phenobarbital or levetiracetam are commonly used to manage seizures. While they don’t treat the tumor itself, these medications can significantly improve the cat’s quality of life and reduce risk of injury from seizure episodes.

Is surgery always necessary for treatment?

Surgery is considered when the tumor is well-defined and accessible, such as in the case of certain meningiomas. However, not all cats are good surgical candidates, especially those with underlying health conditions or tumors in difficult-to-reach locations.

How long can a cat live with brain cancer?

Survival time varies widely. Cats with surgically removed meningiomas may live more than two years, especially with radiation. In contrast, cats with aggressive gliomas or untreated tumors may live only a few weeks to a few months after diagnosis.

Are certain cat breeds more prone to brain cancer?

Some evidence suggests Persian and Siamese cats may have a higher incidence of certain tumor types, possibly due to genetic factors. However, brain tumors can occur in any breed, and environmental and age-related factors also contribute to risk.

Can brain cancer in cats be confused with other conditions?

Yes, many neurological or metabolic diseases mimic brain cancer symptoms. Vestibular disease, hepatic encephalopathy, toxoplasmosis, and high blood pressure can all cause similar signs. That’s why imaging is crucial for an accurate diagnosis.

Is radiation therapy safe for cats?

Radiation is generally well-tolerated in cats and is often used when surgery isn’t possible or doesn’t fully remove the tumor. Side effects are usually mild but may include temporary lethargy or skin irritation. It is performed under anesthesia and requires multiple sessions.

What is the role of corticosteroids in brain cancer treatment?

Corticosteroids like prednisone reduce inflammation and cerebral edema (swelling), which can relieve pressure-related symptoms. While not a cure, these medications can significantly improve comfort and function during the course of the disease.

When should euthanasia be considered?

Euthanasia becomes a humane option when symptoms become unmanageable, the cat no longer enjoys basic activities like eating or grooming, or there are repeated seizures or unrelenting pain. Quality-of-life assessments can help guide this difficult decision.

Can brain cancer spread to other parts of the body in cats?

Primary brain tumors rarely metastasize outside the brain, but systemic cancers (like lymphoma) can affect the brain. It’s also possible for other cancers to metastasize to the brain. Each scenario has unique implications for treatment and prognosis.