Colorectal Cancer vs IBS: Understanding the Differences, Symptoms, and Overlap

- Colorectal Cancer and IBS: Why They’re Often Confused

- The Role of Age, Risk Factors, and Family History

- IBS Symptoms vs. Colorectal Cancer Symptoms: Key Differences

- Diagnostic Challenges and Why Misdiagnosis Happens

- When to Suspect Colorectal Cancer Instead of IBS

- How Colorectal Cancer Develops in the Body

- Overlap Syndromes: When IBS and Cancer Coexist

- IBS Subtypes and Their Diagnostic Impact

- Screening Tools: Colonoscopy, FIT, and Imaging

- Comparing Key Features of IBS and Colorectal Cancer

- Treatment Paths: Managing IBS vs. Treating Cancer

- Impact on Quality of Life and Mental Health

- Surveillance and Follow-up: How Monitoring Differs

- Misconceptions and Myths: Clearing Up Confusion

- When to See a Specialist

- Public Awareness and Future Trends in Diagnosis

- FAQ: Colorectal Cancer vs IBS

Colorectal Cancer and IBS: Why They’re Often Confused

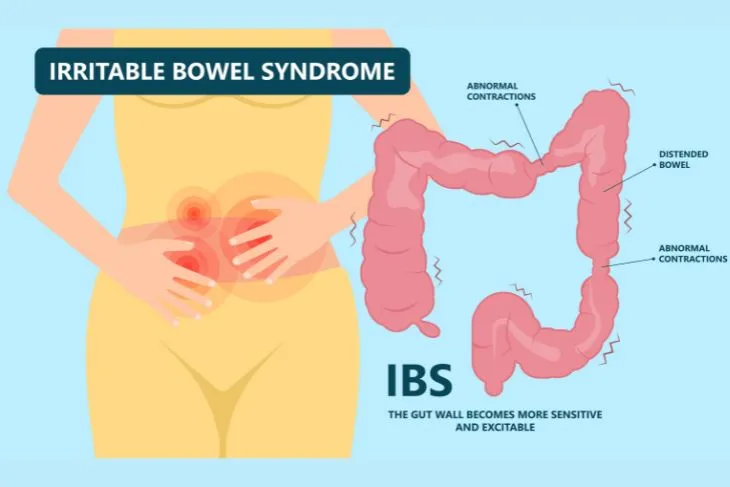

Colorectal cancer and irritable bowel syndrome share several overlapping symptoms—most notably, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, and bloating. This similarity often leads to confusion both among patients and, at times, healthcare providers. However, the nature and cause of these symptoms differ significantly, and misinterpreting them can delay proper diagnosis and treatment.

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder. This means that while symptoms are real and distressing, they aren’t caused by visible structural damage or tumors in the bowel. The colon appears normal under endoscopy, and no cancerous changes are found. In contrast, colorectal cancer involves the actual growth of malignant cells in the colon or rectum. It may begin as a small polyp and evolve into a cancerous lesion over years.

The confusion is understandable, especially in early stages of colorectal cancer, when symptoms may be subtle. Many patients report irregular stools, bloating, and fatigue—identical to IBS complaints. However, as colorectal cancer progresses, it tends to produce red flag symptoms such as unintentional weight loss, visible blood in stool, and persistent fatigue from anemia, which are rare in classic IBS.

The Role of Age, Risk Factors, and Family History

One of the key distinctions between IBS and colorectal cancer lies in who tends to get each condition. IBS often emerges in younger adults, with a higher prevalence in women under 50. It’s frequently associated with stress, diet, gut-brain interaction, and sometimes post-infectious syndromes. Meanwhile, colorectal cancer risk increases significantly after age 50, though cases are rising in younger adults.

Family history is another powerful predictor. If a first-degree relative has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer, especially before age 60, your own risk increases two to fourfold. IBS, on the other hand, can run in families but is not considered a genetically inherited disease in the same sense. The clustering of IBS in families is thought to reflect shared environment, diet, and microbiome composition rather than mutation-driven cancer risk.

Additional cancer risk factors include inflammatory bowel diseases like ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, smoking, high red meat consumption, low fiber intake, and obesity. While IBS may coexist with these factors, it is not driven by them and does not lead to cancer over time.

This type of risk stratification is crucial, and parallels the kind of cellular and molecular risk discussed in the eukaryotic cell cycle and cancer in depth, where genetic and external triggers can drive long-term transformation.

IBS Symptoms vs. Colorectal Cancer Symptoms: Key Differences

Though symptoms may initially appear similar, their characteristics differ on closer examination. IBS symptoms typically fluctuate—they worsen during stress, improve after bowel movements, and often come in cycles. Pain from IBS is crampy, generalized across the abdomen, and relieved by passing gas or stool.

In contrast, pain from colorectal cancer tends to localize in one part of the abdomen, often the lower left quadrant. It may become constant, not relieved by bowel movements, and progressively worsens. While IBS is associated with diarrhea, constipation, or both, colorectal cancer may mimic these but is more likely to cause narrowed stools, persistent constipation, or diarrhea that does not respond to typical treatments.

Another key difference is the presence of visible or occult blood. Blood in the stool is never part of IBS. If blood appears—either bright red or dark and tarry—it must be investigated for serious conditions, including colorectal cancer. Similarly, unexplained weight loss and iron deficiency anemia are rare in IBS but classic warning signs for malignancy.

Clinically, IBS is diagnosed using Rome IV criteria, which require symptoms to be present for at least six months. Colorectal cancer, however, is diagnosed with colonoscopy, biopsy, and imaging—tools designed to detect structural and cellular abnormalities.

Diagnostic Challenges and Why Misdiagnosis Happens

Despite technological advancements, colorectal cancer is still misdiagnosed or diagnosed late in some patients. This happens for several reasons, especially when early symptoms mimic benign conditions like IBS or hemorrhoids. In younger adults, providers may delay referral for colonoscopy under the assumption that the symptoms are functional.

Another issue is the underuse of screening tools. Many patients under 45 do not meet the age threshold for routine colonoscopies, and unless red flag symptoms are present, they may not be prioritized for further evaluation. This creates a diagnostic blind spot for early-onset colorectal cancer, which is on the rise globally.

Laboratory tests such as fecal occult blood testing (FOBT) or fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) can help detect hidden blood loss, but they don’t differentiate IBS from cancer. Imaging and endoscopic tools remain the gold standard, yet they require clinical suspicion to be ordered.

The role of patient advocacy becomes critical. Individuals experiencing persistent bowel changes, rectal bleeding, or fatigue should request evaluation beyond surface-level symptom control. Clinicians must also balance statistical risk with personalized symptoms to avoid anchoring bias.

Wanting clarity early on is something patients face in other domains of oncology as well, as seen in topics like refusing hormone therapy for breast cancer, where early decision-making dramatically alters outcomes.

When to Suspect Colorectal Cancer Instead of IBS

While both conditions can present similarly, there are clinical warning signs that should always trigger suspicion of colorectal cancer over IBS. These include rectal bleeding, especially if persistent or mixed with stool; unintentional weight loss; ongoing fatigue without clear cause; a sudden and unexplained change in bowel habits after age 40; and the presence of iron deficiency anemia.

Another red flag is nighttime symptoms. IBS rarely wakes patients from sleep, but colorectal cancer-related pain or urgency can occur at night. If diarrhea or cramping interrupts sleep repeatedly, it may warrant further investigation. Additionally, any new onset of symptoms in a person with no prior history of bowel problems should not be automatically attributed to IBS.

If a patient has tried dietary changes, probiotics, fiber, and anti-spasmodic medications with no relief, and symptoms persist or escalate, malignancy should be considered. Diagnostic delay is most dangerous in these cases, especially if the assumption of IBS leads to months of ineffective symptom management without further testing.

How Colorectal Cancer Develops in the Body

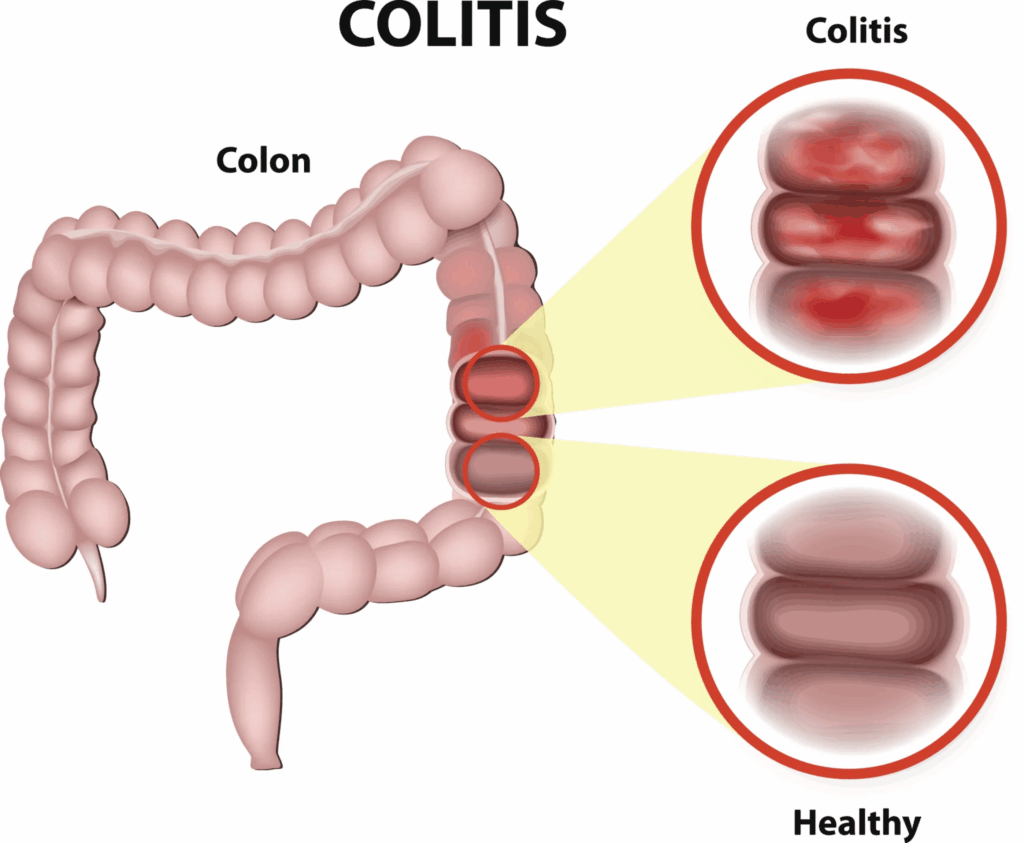

Colorectal cancer usually begins with the transformation of normal glandular cells in the inner lining of the colon or rectum. These changes often arise from adenomatous polyps—small growths that can progress over years from benign to precancerous to malignant. This multistep process, known as the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, is influenced by genetic mutations, inflammation, diet, and environmental exposures.

The first changes occur at the cellular level, often invisible on standard blood tests or imaging. Mutations in genes such as APC, KRAS, and TP53 are frequently involved. These mutations interfere with normal cell cycle regulation, promoting uncontrolled growth, resistance to apoptosis (programmed cell death), and the ability to invade nearby tissues.

As the tumor enlarges, it may erode blood vessels, trigger immune responses, and alter bowel function. In advanced stages, cancer can metastasize to the liver, lungs, or peritoneum. Unlike IBS—which involves no structural tissue changes—colorectal cancer is a physical, measurable disease that progresses if untreated.

Interestingly, some studies have explored whether prolonged tissue irritation or inflammation—seen in both IBS and other chronic GI conditions—might contribute to cellular stress. While no direct pathway has been confirmed between IBS and cancer, the concept mirrors the discussion in does polyester cause cancer, where surface exposure and low-grade inflammation are explored as long-term factors.

Overlap Syndromes: When IBS and Cancer Coexist

Although IBS does not cause colorectal cancer, they can exist in the same patient. This is especially important in older individuals or those with long-standing IBS who begin to experience new symptoms. Clinicians must guard against cognitive bias—assuming all complaints are part of the functional disorder and missing an underlying malignancy.

In some cases, colon cancer may be missed for months or even years if its symptoms are subtle and incorrectly attributed to irritable bowel. Constipation and bloating, for example, are common in both conditions. Only when bleeding, anemia, or weight loss occur does the possibility of cancer come to the forefront.

The psychological component can further complicate diagnosis. Patients with IBS often experience health-related anxiety and may feel dismissed by providers. If new or changing symptoms are brushed off as “just stress,” the diagnostic window for cancer may close prematurely. Careful follow-up, respect for patient concerns, and flexible diagnostic plans are essential to avoid this scenario.

IBS Subtypes and Their Diagnostic Impact

IBS is not a single disorder—it includes subtypes based on dominant symptoms: IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), and mixed-type IBS (IBS-M). Each subtype may resemble different colorectal cancer presentations, adding complexity to differential diagnosis.

IBS-D, for example, shares symptoms with left-sided colorectal cancer, such as urgency and loose stools. IBS-C may mimic obstructive tumors in the distal colon, causing constipation, straining, and incomplete evacuation. IBS-M, with alternating symptoms, overlaps with early colon cancer that intermittently blocks stool flow.

Knowing the subtype helps guide treatment, but also ensures clinicians don’t overlook the need for imaging or endoscopy when symptoms shift. For instance, if an IBS-C patient begins experiencing night sweats or anemia, it should trigger an immediate reassessment of diagnosis, regardless of past GI history.

Unlike cancer, IBS does not cause rectal bleeding, systemic symptoms, or structural tissue change. Differentiating the two is possible, but requires vigilance, awareness of progression, and a willingness to repeat evaluation when clinical status evolves.

Screening Tools: Colonoscopy, FIT, and Imaging

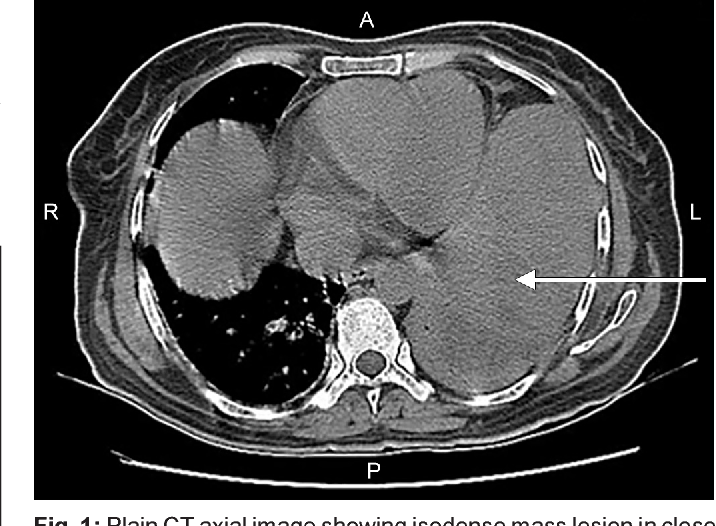

The gold standard for detecting colorectal cancer is colonoscopy. This endoscopic procedure allows direct visualization of the inner lining of the colon and rectum and provides the opportunity to biopsy or remove suspicious lesions immediately. Polyps can be snared and analyzed, while full-thickness tumors are biopsied for histological diagnosis.

For patients with low to moderate risk or without red flag symptoms, non-invasive tests like the fecal immunochemical test (FIT) or guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (FOBT) can help screen for hidden blood in stool. These are useful tools but are not diagnostic. A positive result on FIT requires prompt follow-up with colonoscopy. Stool DNA tests like Cologuard are also emerging as helpful in certain populations.

Imaging modalities such as CT colonography (“virtual colonoscopy”) or abdominal CT scans can be used if colonoscopy is incomplete or contraindicated. However, these tools may miss flat lesions or provide limited information on histological characteristics. Ultimately, biopsy remains essential for definitive diagnosis of cancer.

These tools are not used to diagnose IBS, which is defined by symptom criteria and supported by normal test results. That’s why negative findings in IBS are just as important—they rule out serious pathology and build confidence in a functional diagnosis.

Comparing Key Features of IBS and Colorectal Cancer

| Feature | Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) | Colorectal Cancer |

| Onset Age | Typically under 50 | Typically over 50, but rising in younger adults |

| Nature of Condition | Functional, no visible tissue damage | Structural, with tumor formation |

| Pain Pattern | Cramping, relieved by defecation, fluctuates | Constant, localized, worsens over time |

| Stool Changes | Diarrhea, constipation, or both (alternating) | Persistent narrowing, blood, or obstruction |

| Blood in Stool | Absent | Often present (visible or occult) |

| Systemic Symptoms | Rare | Common (anemia, weight loss, fatigue) |

| Diagnosis | Based on symptoms (Rome IV criteria) | Requires imaging, colonoscopy, biopsy |

| Progression Risk | Does not progress to cancer | Progresses if untreated |

| Treatment Focus | Symptom management | Surgical, oncologic, sometimes palliative |

| Nighttime Symptoms | Rare | Possible, especially in advanced stages |

Treatment Paths: Managing IBS vs. Treating Cancer

IBS treatment is centered around symptom control and lifestyle modification. Dietary changes—such as reducing FODMAP intake—play a central role, along with stress management, physical activity, and sometimes cognitive behavioral therapy. Pharmacological options include anti-spasmodics, anti-diarrheals, laxatives, and gut-brain modulators like SSRIs or tricyclic antidepressants.

Colorectal cancer, by contrast, follows a structured oncologic treatment pathway. Early-stage disease may be treated with surgical resection alone. For more advanced cases, chemotherapy (such as FOLFOX or CAPOX regimens), radiation therapy, and targeted agents (e.g., anti-EGFR or anti-VEGF drugs) are used based on molecular tumor profiling. Stage IV disease may require palliative care, stenting for obstructions, or hepatic metastasis resection.

Whereas IBS rarely requires hospitalization, colorectal cancer may necessitate intensive inpatient care during diagnosis, surgery, and treatment. IBS can impact quality of life, but cancer affects both quality and survival. Therefore, distinguishing between these two early is critical not only for effective care, but for long-term prognosis.

Impact on Quality of Life and Mental Health

Both conditions can severely affect daily functioning, but in different ways. IBS tends to be chronic, unpredictable, and emotionally distressing. Patients often feel embarrassed, misunderstood, or unsupported. The social burden—avoiding meals out, unpredictable urgency, fear of symptoms in public—can create persistent anxiety and even depression.

Colorectal cancer imposes a different burden. Fear of death, treatment toxicity, surgery, and long recovery times can all be psychologically devastating. The physical toll of cancer—fatigue, pain, digestive disruptions—often requires psychological as well as medical support. Survivors may face lasting changes in bowel function, including incontinence or colostomy use.

Interestingly, both groups report feeling dismissed by providers. IBS patients often feel labeled as anxious or overreactive. Cancer patients may feel reduced to a diagnosis, without full acknowledgment of their lived experience. Addressing mental health and validating symptoms is essential in both cases, and the model of integrated care is increasingly applied across GI specialties.

Surveillance and Follow-up: How Monitoring Differs

After diagnosis, the long-term monitoring strategies for IBS and colorectal cancer diverge sharply. IBS does not require routine imaging, colonoscopies, or laboratory testing unless new symptoms arise. Management is primarily symptom-based, and follow-up focuses on quality of life, medication adjustment, and flare prevention.

In contrast, colorectal cancer involves a highly structured follow-up protocol. For stage I–III cancers, regular colonoscopies are typically performed at 1, 3, and 5 years post-surgery. Surveillance blood tests, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels, and periodic CT scans are used to monitor for recurrence. If metastasis was present, imaging and systemic evaluations are more frequent.

Recurrence of colorectal cancer often happens within the first three years. Close follow-up during this window is essential. Any new symptom, especially bowel changes, pain, or weight loss, must be taken seriously. IBS patients do not face such oncologic risks, though symptom monitoring remains important for comfort and function.

Misconceptions and Myths: Clearing Up Confusion

A common misconception is that IBS can “turn into” colorectal cancer. This is false. IBS does not cause cellular mutations, tissue erosion, or tumor growth. It is a separate condition, and while both can occur in the same individual, one does not evolve into the other.

Another myth is that a person is too young for colon cancer. While age is a risk factor, early-onset colorectal cancer is increasing globally, especially among those in their 30s and 40s. Symptoms should never be dismissed due to age alone.

Some people believe fiber cures IBS or prevents cancer. While fiber helps regulate stool and can be protective, it’s not a cure. In fact, fiber worsens symptoms in some IBS patients, especially those with IBS-D. Cancer prevention involves screening, healthy diet, weight management, and avoiding carcinogens—not fiber alone.

Finally, many assume that absence of bleeding rules out cancer. Yet, some right-sided colorectal cancers bleed microscopically and are detected only through anemia or stool tests. Similarly, the presence of gas, bloating, or constipation doesn’t automatically mean IBS—these symptoms can be shared across multiple diagnoses.

When to See a Specialist

Anyone experiencing persistent digestive symptoms for more than four weeks should consult a physician. If those symptoms include rectal bleeding, weight loss, anemia, or a family history of colorectal cancer, a referral to a gastroenterologist is warranted. Early evaluation significantly improves outcomes in cancer cases.

For IBS, specialists are usually brought in when first-line treatments fail, or if the diagnosis is unclear. Gastroenterologists can help fine-tune therapy, identify dietary triggers, and evaluate for co-existing conditions such as bile acid malabsorption, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or pelvic floor dysfunction.

If cancer is confirmed, the care team expands to include oncologists, surgeons, nutritionists, and often mental health professionals. The multidisciplinary approach ensures comprehensive treatment that addresses both survival and post-treatment quality of life.

Clear pathways of referral and open patient-provider communication are critical to timely diagnosis and avoiding mismanagement—especially in cases where symptoms resemble IBS but harbor something more serious beneath the surface.

Public Awareness and Future Trends in Diagnosis

Awareness campaigns for colorectal cancer screening have helped improve early detection, but gaps remain—particularly in younger populations and underserved communities. IBS, despite affecting up to 15% of the population, also suffers from underrecognition and stigma, often perceived as a “nervous stomach” rather than a legitimate disorder.

Future diagnostic trends are shifting toward non-invasive biomarker testing, genetic screening, and artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted colonoscopy. These tools may one day reduce reliance on invasive procedures and identify cancer risk earlier. For IBS, microbiome analysis, gut-brain axis research, and personalized nutrition plans are gaining traction.

Public health messaging must emphasize that colorectal cancer is preventable and treatable when caught early. Simultaneously, IBS needs de-stigmatization so patients can seek care without shame or dismissal.

It’s important to approach both conditions with the nuance they deserve—whether discussing structural disease or functional disturbance, biology or psychology, chronicity or curability. This same principle applies across disciplines, even in areas seemingly unrelated, as seen in does polyester cause cancer, where long-term exposure patterns challenge conventional thinking.

FAQ: Colorectal Cancer vs IBS

Can IBS lead to colorectal cancer?

No, IBS does not lead to or increase the risk of colorectal cancer. The two are distinct conditions with different biological mechanisms.

What is the main difference between colorectal cancer and IBS symptoms?

Colorectal cancer symptoms often include blood in the stool, weight loss, and fatigue, while IBS symptoms are more functional—like cramping, bloating, and irregular bowel habits without systemic signs.

How can doctors tell IBS from colorectal cancer?

Doctors rely on symptom history, physical exams, lab tests, and, most importantly, colonoscopy. IBS has normal test results, while colorectal cancer shows structural changes.

Is it possible to have both IBS and colorectal cancer?

Yes, it is possible to have both, especially if a person with IBS develops new symptoms later in life. Each condition requires its own evaluation and management.

Does rectal bleeding always mean cancer?

No, but it should never be ignored. Hemorrhoids, infections, and anal fissures can also cause bleeding, but cancer must be ruled out with appropriate testing.

Can people under 40 get colorectal cancer?

Yes. Although less common, colorectal cancer is rising in people under 40. Any persistent bowel changes in this age group should be evaluated.

Does IBS cause weight loss or anemia?

No. If you are losing weight or showing signs of anemia, it is essential to investigate for other causes, including malignancy.

Are IBS symptoms consistent or do they come and go?

IBS symptoms typically fluctuate and are often linked to diet, stress, or hormonal cycles. They may improve after bowel movements.

How long should I wait before seeing a doctor about bowel changes?

If symptoms last more than 4 weeks, or if red flags like bleeding or weight loss are present, seek medical attention promptly.

Can stress cause colorectal cancer like it does IBS?

Stress can worsen IBS but does not cause colorectal cancer. Cancer develops due to genetic and environmental factors, not psychological stress alone.

Are there blood tests to tell IBS from cancer?

Not definitively. Blood tests may show anemia in cancer but are usually normal in IBS. Diagnostic imaging and colonoscopy are more reliable.

Do IBS medications help with colorectal cancer symptoms?

No. Medications for IBS will not treat cancer and may delay proper diagnosis if used without further evaluation.

Can dietary fiber cure or prevent either condition?

Fiber may help manage IBS symptoms and may reduce cancer risk, but it is not a cure for either condition.

Is colonoscopy necessary if I’m young with IBS symptoms?

If you have red flag symptoms, a colonoscopy may still be recommended regardless of age. Each case should be individually assessed.

What if my doctor says it’s just IBS, but I feel worse?

You should advocate for further testing, especially if your symptoms are changing, worsening, or accompanied by red flags. Second opinions are always an option.