Melanoma: The Most Dangerous Skin Cancer Explained

- Foreword

- Part One: What Is Melanoma?

- Part Two: What Melanoma Looks Like — and How to Spot It

- Part Three: How Melanoma Is Diagnosed

- Part Four: Staging and Prognosis

- Part Five: Treatment Options Overview

- Part Six: Melanoma That Spreads

- Part Seven: Melanoma and Other Cancers

- Part Eight: Living After Melanoma

- Part Ten: Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

Skin cancer doesn’t always look like cancer. It doesn’t always come with pain or a warning or a sense of urgency. It can start with something small — a freckle, a mole, a mark that seems to change slightly, then slowly, then more. Melanoma grows in silence until it doesn’t. And by the time it calls out, it may have already moved.

If you’re reading this, you might be trying to understand a diagnosis, or maybe you’ve noticed something strange on your skin. Maybe a loved one is facing treatment, or you’re simply here because you heard the word “melanoma” and realized you didn’t know what it meant beyond “serious.”

This article was written for that moment. The one where concern turns into questions, and questions need answers that go deeper than headlines and health pamphlets.

Melanoma is often called the most dangerous form of skin cancer — not because it’s the most common (it isn’t), but because of how quickly and unpredictably it can spread. And yet, caught early, it’s highly treatable. That’s the paradox. What makes it dangerous also makes it possible to survive — if you know what to look for, when to act, and how to navigate the options.

In the pages ahead, we’ll walk through every part of this disease: from early skin changes and diagnostic steps, to advanced-stage therapies and the emotional toll of life after treatment. We’ll cover the science without losing sight of the human weight behind every term. We’ll talk about moles on ears, lymph node biopsies, immunotherapy side effects, and what happens when melanoma collides with other cancers like breast or liver disease.

If you’re here to learn, you’re in the right place. If you’re here because you’re scared, that’s okay too. The answers won’t always be easy, but they’ll be real.

Let’s begin.

Part One: What Is Melanoma?

Most skin cancers stay local. They grow slowly, they sit on the surface, and even when they look rough or strange, they tend to stay where they started. Melanoma doesn’t follow that pattern. It begins in the same place — the skin — but it behaves like something entirely different. It’s faster. It’s more invasive. And if it isn’t caught early, it has a habit of slipping past the skin and into places that are much harder to reach.

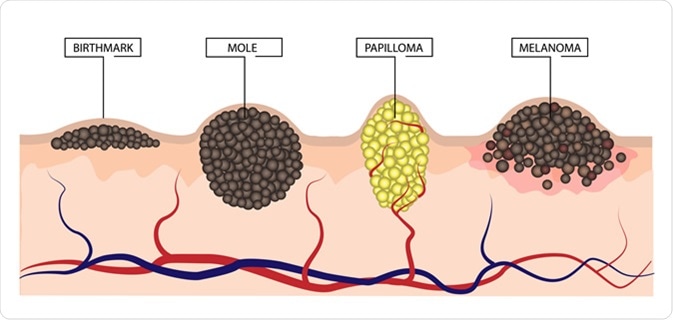

Melanoma starts in the melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the skin. These are the cells responsible for freckles, tanning, and the varying shades of brown, black, or red that give moles and birthmarks their color. Normally, melanocytes help protect us from ultraviolet (UV) radiation. But sometimes, usually after years of sun exposure — or in some cases, due to genetic mutations — these cells begin to grow out of control. That’s where melanoma begins.

But not all melanomas look the same — or behave the same.

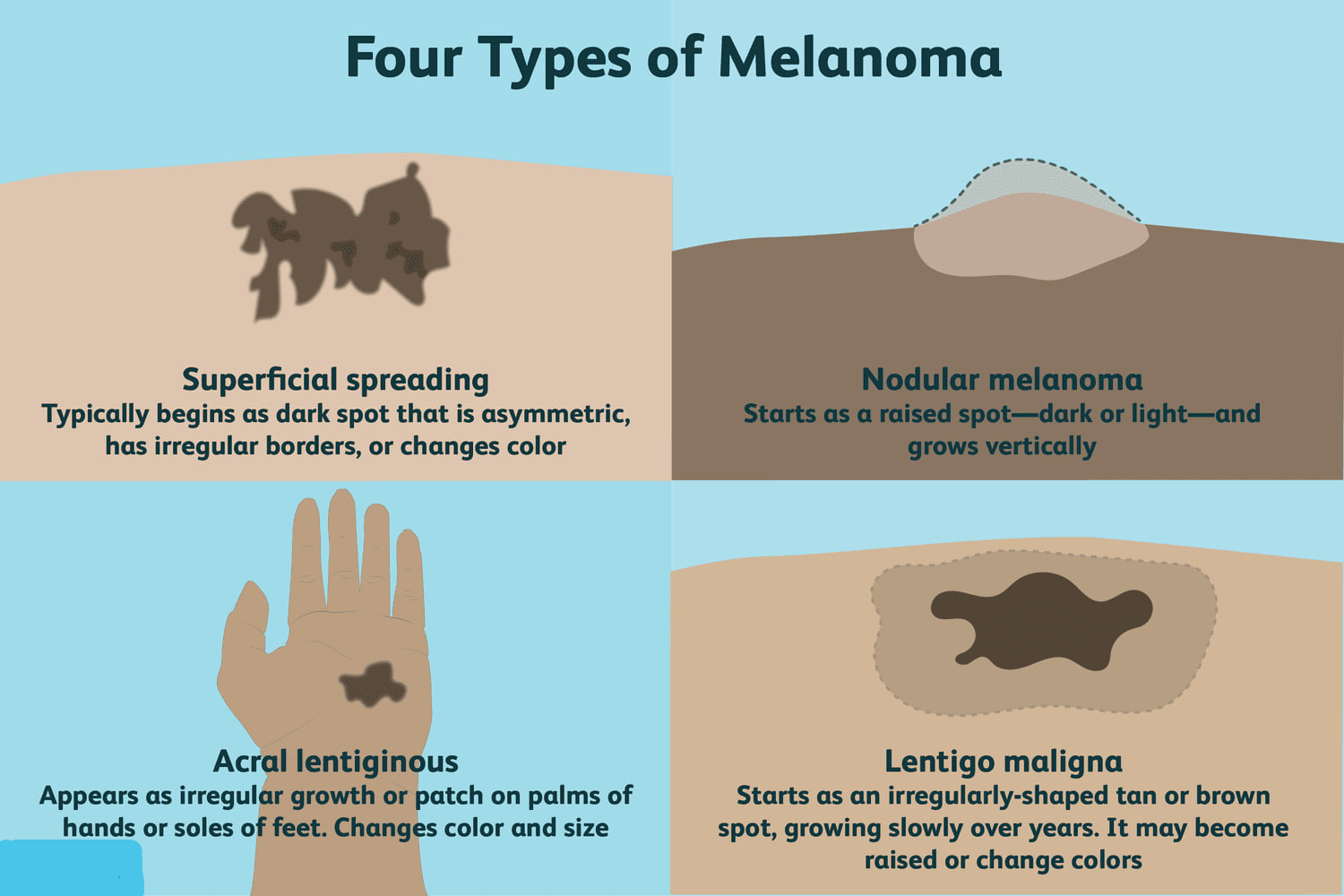

The Four Main Types of Melanoma

The most common form is called superficial spreading melanoma. It often starts as a flat or slightly raised lesion with irregular borders and mixed coloring — usually brown, black, red, or tan. It tends to grow outward across the surface of the skin before invading deeper. It’s also the type most often seen in middle-aged adults, and it can appear anywhere — not just in sun-exposed areas.

Then there’s nodular melanoma, a more aggressive form that grows downward instead of across. It usually appears as a firm, raised bump that may be black, blue, or reddish. Unlike superficial spreading melanoma, which may linger on the surface for months, nodular melanoma tends to invade quickly. It accounts for a smaller share of cases but is more likely to be caught at a later stage.

Lentigo maligna melanoma typically develops in older adults, often on the face or other areas with chronic sun exposure. It begins as a large, flat patch of discolored skin — sometimes mistaken for age spots — and grows slowly at first, sometimes over years. If caught in its early, non-invasive form (lentigo maligna), it can often be removed before it turns dangerous.

The least common but most overlooked is acral lentiginous melanoma, which appears on the palms, soles, or under the nails. It’s more frequently seen in people with darker skin and is often diagnosed late, simply because these locations are less likely to be checked or suspected. It doesn’t arise from sun damage but can be just as aggressive.

Rare and Hidden Forms

Beyond the skin, melanoma can also arise in unexpected places. Mucosal melanoma appears in the lining of the nose, mouth, throat, or genital tract — areas with no sun exposure at all. Ocular melanoma, which develops in the eye’s uveal tract, can impair vision or go unnoticed until it’s quite advanced.

These types are rare but not impossible. They serve as reminders that melanoma isn’t just a sunburn story — it’s a disease of pigment cells, wherever they exist.

Why It’s More Dangerous Than Other Skin Cancers

Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma — the two most common skin cancers — tend to grow slowly and stay local. Even when left untreated, they rarely spread far. Melanoma is different. It has a greater tendency to enter the lymphatic system and bloodstream, allowing it to travel to organs like the liver, lungs, brain, or bones. Once it spreads, it becomes significantly harder to treat.

That’s why early detection is so critical. A melanoma that’s still within the top layer of skin — the epidermis — can often be cured with a simple surgical excision. But once it penetrates deeper into the dermis and reaches blood vessels or lymph nodes, the risks escalate dramatically.

The difference between a Stage I melanoma and a Stage IV one isn’t just depth — it’s destination.

And Yet — It’s Often Curable

The paradox is this: for all its danger, melanoma is often caught early. People notice it. They see a mole changing, or a new spot that doesn’t look right, and they ask their doctor. Unlike many internal cancers that grow unseen for years, melanoma announces itself — if someone knows to look.

And when it’s caught early, melanoma is one of the most curable cancers in existence. Surgery can be curative. No chemo, no radiation, no immunotherapy — just a clean removal, clear margins, and follow-up skin checks.

That’s why awareness matters. That’s why a little education about moles and skin exams can make all the difference. Because even the most dangerous skin cancer doesn’t need to become deadly — if it’s caught before it spreads.

Part Two: What Melanoma Looks Like — and How to Spot It

You’d think a dangerous skin cancer would be easy to recognize. Something alarming. Obvious. But melanoma doesn’t always look like trouble. Sometimes it shows up as a small brown patch that fades into the background. Sometimes it looks like a normal mole, just slightly… different. And sometimes it appears where you wouldn’t think to check at all — between toes, under a fingernail, or on the back of the ear where the mirror doesn’t reach.

That’s why catching melanoma early is as much about noticing change as it is about spotting textbook symptoms. It’s not just about what it looks like — it’s about how it behaves.

The ABCDEs of Melanoma

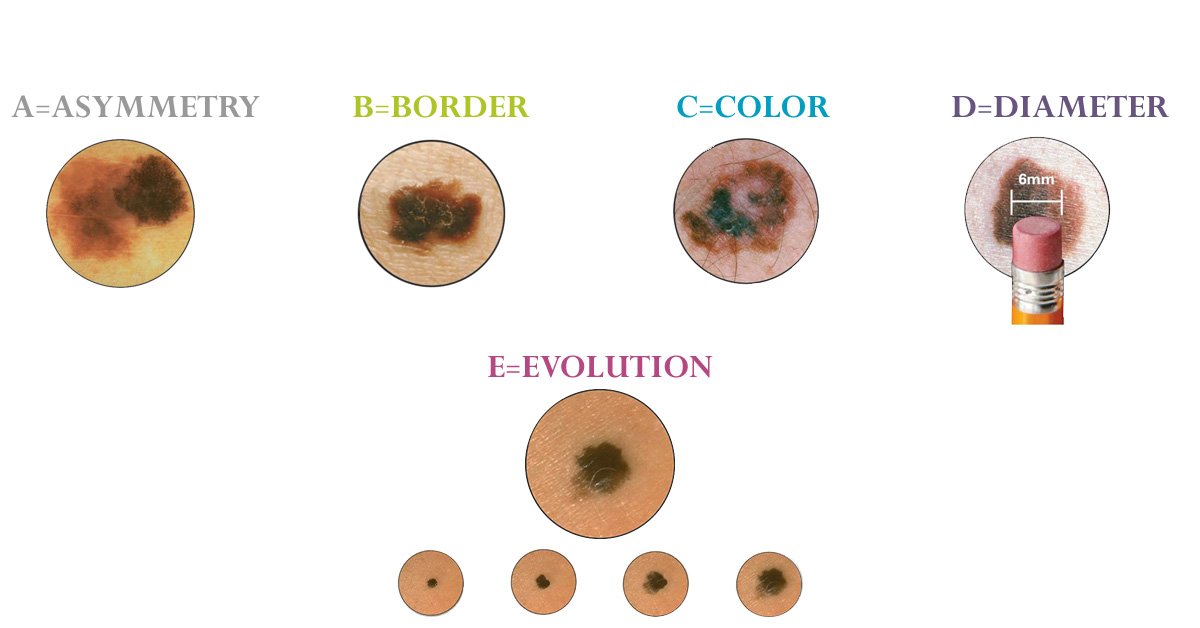

Most skin cancer education starts with a memory trick: the ABCDEs. It’s a simple framework, and it works — if you know what you’re looking for.

- Asymmetry: If you drew a line through the middle of the mole, would both halves match? Melanomas tend not to be symmetrical.

- Border: Look at the edges. Melanomas often have uneven, scalloped, or blurred borders — not clean circles.

- Color: Harmless moles usually have one shade. Melanomas may contain multiple — brown, black, red, even blue or white areas.

- Diameter: Size isn’t everything, but anything larger than a pencil eraser (about 6 mm) should raise suspicion — especially if it’s growing.

- Evolving: Change is key. Any mole that starts to grow, itch, bleed, or shift in appearance over time needs attention, even if it used to seem normal.

This pattern isn’t perfect. Some melanomas skip these rules entirely. They might be small, round, pale, or colorless — called amelanotic melanomas — and they’re harder to recognize because they don’t follow expectations. But for most people, the ABCDE guide is a starting point. It gives language to that gut feeling that something isn’t right.

Melanoma in Early Stage: What That Actually Means

The phrase early-stage melanoma gets thrown around often, but it’s worth unpacking.

When melanoma is caught early — meaning before it has invaded deeply into the skin — it’s classified as Stage 0 or Stage I. Stage 0, also called melanoma in situ, means the cancer cells are still confined to the top layer of skin, the epidermis. They haven’t broken through. These are nearly always curable with surgery.

Stage I means the cancer has begun to invade into the dermis, the layer beneath, but hasn’t yet spread to lymph nodes or distant parts of the body. These lesions are often no larger than a few millimeters deep — but even so, they require careful surgical removal with adequate margins. The thinner the melanoma, the better the odds.

What makes melanoma so different is how quickly that can change. A lesion that’s less than a millimeter thick today might become a deeper, riskier tumor in a matter of weeks or months. That’s why waiting to “see what it does” can be risky. If it looks different, or if it’s new and growing — it’s time to check.

Skin of Color, Atypical Locations, and Why Melanoma Gets Missed

Melanoma doesn’t always appear where you’d expect. While the most common locations include the back (especially in men), legs (especially in women), and face, it can also develop in more hidden or overlooked areas.

One of the most underrecognized spots is the ear. Melanoma skin cancer on the ear often presents as a flat patch or slightly raised bump — sometimes crusted, sometimes smooth — and it’s frequently ignored until it’s more advanced. The skin behind the ear, the rim of the helix, or even inside the ear canal can all be involved. These aren’t places most people inspect often, and they can be easy to miss in a mirror.

For people with darker skin, melanoma often appears on the palms, soles, nail beds, or mucous membranes — not necessarily sun-exposed areas. Because it doesn’t always follow the common presentation of dark moles or visible skin changes, diagnosis in these cases is often delayed, and outcomes are worse.

Checking these “non-obvious” areas — the scalp, ears, underarms, between toes, under the nails — can make a real difference. And bringing any new or changing spot to a dermatologist’s attention is never overreacting. Melanoma can develop anywhere melanocytes exist, not just where you got the worst sunburns.

When to Be Concerned — Even If It Doesn’t Look “Bad”

The most dangerous melanomas aren’t always the biggest, darkest, or ugliest. Some are small and quiet. The real red flag is change. A new spot on adult skin is always worth checking — because adults don’t just grow new moles regularly. A mole that suddenly starts itching, bleeding, or becoming raised after years of staying the same isn’t just “aging.” It could be signaling something deeper.

And if your skin has a history — lots of sun damage, a family member who had melanoma, or even a previous skin cancer — you’re already in a higher-risk group. That doesn’t mean panic. It means attention. Self-checks, regular exams, and digital dermoscopy when needed. You don’t need to become obsessed with your moles. But you do need to know your skin well enough to know when something doesn’t fit.

Part Three: How Melanoma Is Diagnosed

A spot changes. A mole looks suspicious. A doctor takes a second look — and from that moment on, the process begins. Diagnosing melanoma is both simple and layered. Simple in the sense that it often starts with a small piece of tissue. Layered because that single biopsy sets off a cascade of decisions, staging studies, and sometimes life-altering news.

But it starts, always, with observation — and then a sample.

The Skin Exam: First Clue, Not Final Answer

The first tool is still the oldest: eyes. Most dermatologists rely on visual inspection, often aided by a dermatoscope — a handheld magnifier with polarized light that lets them see pigment patterns and vascular structures beneath the surface. A trained eye can often spot melanoma based on subtle cues: irregular pigment, asymmetrical patterns, or a change in a long-standing mole.

But no matter how confident a dermatologist feels, no one diagnoses melanoma by sight alone. Suspicion leads to sampling. A biopsy is the only way to confirm.

Types of Biopsy

Depending on the size and location of the lesion, doctors may choose one of several techniques:

- Excisional biopsy: The preferred method whenever possible. The entire mole or suspicious spot is removed with a small margin of normal skin. This allows for full evaluation of depth, which is critical for staging.

- Punch biopsy: A small, circular blade is used to remove a core of skin, often for sampling part of a larger lesion. It’s helpful when the full lesion can’t be removed easily at first.

- Shave biopsy: The top layers of skin are scraped off. It’s quick and often used in primary care settings — but for suspected melanoma, this method risks underestimating depth, which can delay accurate staging. Dermatologists usually avoid it when melanoma is on the differential.

Once tissue is removed, it goes to a pathologist — a specialist who examines cells under a microscope. This is where the diagnosis is truly made.

The Pathology Report: Beyond Yes or No

If the biopsy confirms melanoma, the pathology report becomes the backbone of everything that comes next. It tells the medical team:

- How deep the tumor goes (called Breslow thickness), which is the most important prognostic factor.

- Whether the tumor is ulcerated, which increases risk.

- How many mitoses — signs of cell division — are present, which can indicate aggression.

- The subtype of melanoma: superficial spreading, nodular, acral, etc.

- Whether margins are clear, or if further surgery is needed.

This report determines the stage, guides whether lymph nodes need to be tested, and helps predict what comes next.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

If the melanoma is deeper than about 0.8 mm — or thinner but ulcerated — doctors will often recommend a sentinel lymph node biopsy. This is a surgical test that identifies and removes the first lymph node (or nodes) where cancer would likely spread, if it has begun to travel.

Here’s how it works: a small amount of radioactive tracer and/or blue dye is injected near the tumor site. That tracer flows through the lymphatic channels to the sentinel node. If that node is clear of cancer, the chances of spread are low. If it contains melanoma cells, staging changes — and so does treatment.

This procedure is often done at the same time as the wide local excision (definitive surgery to remove the tumor with a larger margin). It’s not a major operation, but it plays a major role in deciding whether further therapy is needed.

Is There a Blood Test for Melanoma?

This is one of the most common questions — and unfortunately, the answer remains: no, not yet.

There is no routine blood test that can detect melanoma early. Unlike some cancers that produce circulating markers — like PSA for prostate or CA-125 for ovarian — melanoma doesn’t shed a consistent, measurable protein into the blood during its early stages.

That said, research is ongoing. Scientists are studying circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and immune-related markers as potential blood-based tools. In advanced disease, some blood tests (like LDH) may help gauge tumor burden, but they’re not specific enough to serve as screening or diagnostic tests.

So if you’re worried about a mole or skin change, a blood test won’t rule anything out. It has to be examined. It has to be biopsied.

Imaging: When Scans Come Into Play

For early-stage melanoma — say, Stage I — imaging isn’t always needed. If the tumor is thin and the lymph nodes feel normal, scans are unlikely to change the treatment plan.

But in Stage II and above, especially if the sentinel node is positive, imaging becomes more important. Depending on the case, doctors may order:

- CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to look for distant spread.

- PET scans to find metabolically active disease.

- MRI, especially for patients at risk of brain metastases.

These scans don’t confirm melanoma — the biopsy already did that — but they reveal its reach. They define the territory, and help determine whether the next steps involve surgery alone, or systemic therapy as well.

Diagnosing Isn’t Just About Finding It — It’s About Understanding It

Melanoma diagnosis is a stepwise process: spot, biopsy, confirm, stage. But behind each of those steps is a deeper set of questions — how fast is this moving? How far has it gone? What can we still do?

And at every step, the process remains centered around a simple goal: clarity. The better the team understands the tumor, the better they can tailor the treatment.

Part Four: Staging and Prognosis

A diagnosis of melanoma is never just one sentence. It arrives with a weight behind it — not only you have melanoma, but here’s how deep, how far, and how serious it is. That’s what staging is for. It turns a diagnosis into a roadmap. It helps doctors understand what they’re treating, and patients understand what’s ahead.

But for people outside the cancer world, staging can sound cryptic — a string of Roman numerals and decimal points that feel more like coding than care. So let’s slow it down. What does it actually mean to be stage 0, or stage II, or stage IV? And how much does that number tell you about the future?

The Basics: What Staging Measures

At its core, melanoma staging tries to answer three questions:

- How deep is the tumor?

- Has it spread to lymph nodes?

- Has it spread to distant organs?

From there, the cancer is assigned a stage between 0 and IV. The lower the stage, the more local and curable it is. The higher the stage, the more systemic and complex it becomes. But the nuances matter.

Take Stage 0, also called melanoma in situ. This is the earliest possible diagnosis. The abnormal cells are confined to the epidermis — the outermost layer of skin. They haven’t breached the basement membrane. They haven’t moved. Surgery to remove the lesion with a clean margin is usually curative, and the risk of recurrence is minimal.

Once the melanoma moves into Stage I, it means the cancer has started to invade. At this point, the tumor is still thin — usually under 2 millimeters — and hasn’t yet reached lymph nodes or organs. These are still considered early-stage melanomas, and most can be cured with surgery alone. But the difference between 0.6 mm and 1.6 mm can be significant. Deeper tumors carry more risk, especially if they’re ulcerated or have a high mitotic rate, meaning they’re dividing quickly.

Stage II usually involves thicker tumors — over 2 mm, or thinner ones with high-risk features like ulceration. Even without lymph node involvement, Stage II melanoma has a greater chance of recurrence. This is when doctors may begin discussing additional treatments, like immunotherapy, after surgery. It’s also where routine imaging may enter the picture.

Things change substantially with Stage III. At this point, melanoma has spread to nearby lymph nodes or to the skin just beyond the original tumor site. This doesn’t always mean it’s visible — sometimes the spread is microscopic, found only through sentinel lymph node biopsy. But once melanoma reaches the lymphatic system, treatment broadens. Surgery is still important, but systemic therapy often becomes part of the plan. Stage III melanoma used to carry a grim outlook. Today, with immunotherapies and targeted treatments, many patients do well. But the stakes are higher.

And then there’s Stage IV — when melanoma has spread to distant organs. The lungs. The liver. The brain. Sometimes the bones. It no longer fits in one place. For many years, this stage was synonymous with poor outcomes. But over the past decade, Stage IV melanoma has become a frontier of rapid progress. People who once had months to live are now surviving for years, even longer, with treatments that were considered experimental just a few summers ago.

That said, Stage IV is still a turning point. Treatment shifts from curative to life-extending. The focus becomes keeping the disease in check — reducing its size, slowing its growth, controlling symptoms — and buying time. Sometimes years. Sometimes decades. Every case is different.

Prognosis: Numbers vs. Real Life

You’ll see survival statistics quoted all over the place. Five-year survival rates. Recurrence percentages. These numbers can be useful, but they rarely tell the full story.

For example, early-stage melanoma (Stage 0–I) carries a five-year survival rate close to 98–100%, assuming clean surgical margins. Stage II survival depends heavily on the exact depth and biology, but ranges from 80% down to 50%depending on the details. For Stage III, survival used to average around 40–60% — now it’s improving with newer therapies. And for Stage IV, survival rates vary wildly: some patients live just months, others several years or more, especially if they respond to checkpoint inhibitors or targeted therapy.

But numbers are just one part of prognosis. Your age, general health, immune system, tumor subtype, genetic markers (like BRAF or NRAS mutations), and how you respond to treatment all matter. Some people with high-stage melanoma live full lives. Some with early-stage disease face a recurrence that no one predicted. Risk is a guide, not a guarantee.

Why Depth Matters So Much

In melanoma, more than in many cancers, the depth of the tumor — the Breslow thickness — is the single most important predictor of outcome. The deeper the cancer goes into the skin, the more likely it is to reach blood vessels or lymphatic channels, and the more likely it is to spread.

A melanoma that’s less than 1 mm deep is considered low-risk. A melanoma that’s greater than 4 mm deep is high-risk, even if lymph nodes are still clear. That’s why biopsy technique matters. A shallow shave biopsy might miss the deepest point of invasion — and mislead the staging.

Depth changes everything. It shapes the margins of surgery. It determines whether lymph nodes are tested. It guides whether systemic treatment is recommended. Which is why pathologists are so exacting when they measure it.

So What Does Staging Mean for You?

It means a plan. If you’re Stage 0 or I, your plan may be straightforward: wide excision, skin checks, and long-term surveillance. If you’re Stage II, you may be discussing immunotherapy or clinical trials. If you’re Stage III or IV, your care becomes a team effort — oncology, surgery, imaging, immunology — with a strategy that adapts over time.

Staging isn’t just paperwork. It’s orientation. It tells your doctors how aggressive to be, how closely to monitor, and how much to prepare. And if your stage feels higher than you expected, or lower than you feared — take a breath. It’s not a verdict. It’s the beginning of your treatment roadmap.

Part Five: Treatment Options Overview

Once the diagnosis is clear and the stage is defined, treatment begins. But melanoma treatment isn’t a single pathway. It’s more like a branching system — with some routes leading to surgery and recovery, others winding into immunotherapy, clinical trials, or maintenance care. And in some cases, it’s all of those things at once.

What matters most in this phase isn’t just what treatment is given — it’s why it’s chosen, and how it fits into the full picture.

For early-stage melanoma, treatment is often surgical and curative. The tumor is removed with a wide margin of normal skin, and that’s it — no chemotherapy, no radiation, just long-term monitoring. But when the tumor is deeper, or lymph nodes are involved, or the cancer has spread to distant sites, everything changes. Treatment becomes more complex — and more powerful.

Surgery: Still the First Line — But Not Always the Last

For most patients, treatment begins with wide local excision — a surgery that removes the melanoma along with a buffer of healthy skin to make sure no cancer cells are left behind. The margin depends on how deep the tumor goes. For in situ cases, it might be half a centimeter. For deeper melanomas, it could be up to two centimeters. It may seem excessive, but in melanoma, even microscopic remnants can lead to recurrence.

In earlier stages, this procedure might be all that’s needed. But as staging increases — particularly once the tumor reaches about 0.8 mm in depth — doctors often consider a sentinel lymph node biopsy, as discussed in Part Three. If that node is positive, more aggressive treatment usually follows.

In Stage III, surgery may also involve removal of involved lymph nodes. But even here, surgery is only part of the story. Increasingly, it’s what comes after surgery that determines long-term outcome.

Immunotherapy: Teaching the Immune System to Fight Back

Melanoma was one of the first solid tumors to respond dramatically to immunotherapy, and that’s changed everything about how advanced disease is treated.

Checkpoint inhibitors — like nivolumab (Opdivo) or pembrolizumab (Keytruda) — work by blocking the brakes on your immune system, allowing T-cells to recognize and attack melanoma cells. For many patients with Stage III or IV disease, these drugs are now front-line therapy.

Some receive them after surgery, to reduce the risk of recurrence. Others receive them without surgery, to shrink or control tumors that can’t be removed. And in Stage IV, where melanoma has spread to distant organs, immunotherapy has made long-term survival a real possibility. Not a miracle — but a hard-won, biologically driven outcome.

Side effects can be serious — ranging from fatigue and rash to inflammation of the colon, lungs, or thyroid — but most are manageable with close monitoring. For some, the side effects are minimal. For others, they require steroids or temporary pauses. Either way, this form of treatment has become the backbone of modern melanoma care.

Targeted Therapy: A Genetic Shortcut (If You Have the Mutation)

Roughly 40–50% of cutaneous melanomas carry a mutation in the BRAF gene, which helps regulate cell growth. When that gene is altered, it causes cells to divide uncontrollably. If you have a BRAF-mutant melanoma, you may be eligible for targeted therapy with drugs like dabrafenib and trametinib, which directly shut down that abnormal signaling.

These pills are often used in advanced or metastatic melanoma and sometimes after surgery in Stage III patients to reduce the chance of recurrence. Unlike immunotherapy, which works indirectly through the immune system, targeted therapy goes straight at the cancer’s internal wiring.

It’s not for everyone — only patients with the right mutation — and resistance can develop over time. But for those who respond, results can be dramatic and fast.

Radiation Therapy: A Supporting Role

Radiation doesn’t cure melanoma by itself. But it can help in specific situations — especially when the tumor is bulky, pressing on vital structures, or located in a hard-to-operate area. It’s also sometimes used after lymph node dissection, if there’s a high risk of regional recurrence.

In metastatic disease, radiation may help control pain, reduce swelling, or shrink a growing mass that’s affecting function. And for brain metastases — a known risk in advanced melanoma — radiation, including stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS), is a key component of treatment.

So while radiation isn’t a main character in early-stage disease, it plays a crucial supporting role when things get more complex.

Clinical Trials and New Frontiers

Melanoma research is moving fast. New combinations of immunotherapies, novel agents like LAG-3 inhibitors, personalized cancer vaccines, and engineered T-cell therapies are all under investigation. Many are available through clinical trials, especially for patients whose cancer has recurred or resisted standard treatments.

These trials aren’t just for people out of options. Sometimes they offer access to cutting-edge drugs that may soon redefine the standard of care. If you’re eligible, and your care team recommends one, it’s worth looking closely.

Treatment for melanoma isn’t just about targeting cancer. It’s about timing, sequencing, biology, and adaptability. One person’s treatment plan may be all surgery and follow-up. Another’s may stretch across years of therapy, remission, and retreatment. There’s no one path — but there are always options.

Part Six: Melanoma That Spreads

For a long time, melanoma was one of the most feared cancers — not because it always started aggressively, but because once it spread, it moved fast. A mole on the shoulder could lead to lesions in the lungs. A patch on the leg could show up again in the brain. And by the time symptoms arrived, options were often few.

That reputation came from a real truth: melanoma metastasizes early, and widely. But now, with better imaging, targeted therapies, and immune-based treatments, the way we handle metastatic disease has changed — even if the disease itself still follows its old patterns.

How Melanoma Spreads — and Why So Easily

Melanoma cells can slip into the bloodstream or lymphatic system surprisingly early. Because the skin is so vascular and lymph-rich, and because melanoma grows from melanocytes embedded across the body, it’s well positioned to travel once it becomes invasive. Unlike some cancers that stay local for years, melanoma can jump from the skin to internal organs even when the original tumor was small.

It doesn’t always follow a linear path. Some patients see a spread to local lymph nodes first, then to distant sites. Others skip the lymph nodes entirely and show up months later with disease in the lungs or brain. That unpredictability is part of why staging and close follow-up are so critical — and why recurrence can sometimes feel sudden.

Common Sites of Metastasis

Melanoma has a handful of favorite places it likes to return to. Some of this is due to blood flow, some to tissue type, and some remains poorly understood. But patterns do emerge.

The lymph nodes are often first. That’s why sentinel lymph node biopsies are done early in staging — they help detect microscopic spread even before it’s visible on scans. Swollen nodes, especially near the original tumor site, can be an early sign of recurrence.

The lungs are a frequent target. Melanoma lung metastases may appear on CT scans before any symptoms show up — though some patients develop a chronic cough or shortness of breath. Small nodules can be watched; larger ones may need treatment.

The liver is another common site — and this is often where the keyword “liver cancer melanoma” causes confusion. Melanoma doesn’t become liver cancer, but it can spread to the liver. These are melanoma metastases, not primary liver tumors. They may present with fatigue, weight loss, elevated liver enzymes, or show up incidentally on imaging. Their presence doesn’t automatically mean treatment ends — systemic therapies, including immunotherapy, can still be effective, even here.

The brain is one of the most serious sites of spread. Melanoma is notorious for crossing the blood-brain barrier. Symptoms can range from headaches and dizziness to seizures or personality changes — or nothing at all, until a scan finds it. This is why many oncologists monitor for brain metastases in Stage III or IV patients, especially those with BRAF mutations or high tumor burden.

Less commonly, melanoma may spread to bones, the gastrointestinal tract, or even the heart. When it does, it often reflects high-grade, late-stage disease — but even here, treatments have improved.

What Does Stage IV Melanoma Mean Now?

Stage IV used to carry a single implication: poor prognosis. But in the post-immunotherapy era, that’s no longer the whole truth.

Today, many patients with Stage IV melanoma live for years, especially if their tumors respond to checkpoint inhibitors like nivolumab or ipilimumab. Some go into long-term remission. Others manage the disease as a chronic condition, alternating between treatments, scans, and periods of stability. The presence of distant spread no longer ends the story — it changes it.

Treatment depends on factors like:

- Location of metastases (brain and liver involvement often require more urgent or layered treatment)

- Number of sites affected

- BRAF mutation status (which can open the door to targeted therapy)

- PD-L1 expression and immune markers

- Response to prior treatment — if any

Therapy may include a combination of immunotherapy and targeted agents, or focus on one pathway depending on side effect profile, tumor load, and speed of disease progression. Radiation is sometimes used to control specific spots, particularly in the brain or bones.

When It Spreads to Just One Organ

There are also rare cases of oligometastatic disease — meaning melanoma has spread, but only to a single organ or a limited number of spots. In these cases, surgical resection or focused radiation may be considered, especially if the rest of the disease appears stable. Some patients even undergo liver or lung resection after systemic therapy, particularly if the immune system seems to have done most of the cleanup already.

This isn’t the norm, but it’s no longer out of reach either. For certain patients, aggressive control of a few metastases can add years of meaningful time — especially when the immune response is strong.

Understanding Spread Without Giving Up

Melanoma is a shape-shifter. It can disappear from the skin and reappear somewhere visceral. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing to do. Spread changes the math, yes — but it doesn’t erase hope.

If the cancer has reached the liver, the brain, or the lungs, the goal is often control over time, not a single cure. But even that can be powerful. People live full lives in the space between scans, between infusions, between treatments that used to feel experimental and are now standard. The landscape is still difficult. But it’s no longer flat.

Part Seven: Melanoma and Other Cancers

Cancer doesn’t always come one at a time. For some people, melanoma is the first diagnosis. For others, it comes second — after years of routine mammograms, or in the middle of treatment for another cancer entirely. That overlap raises questions that are both medical and deeply personal: Are these cancers connected? Did one cause the other? Am I more vulnerable now than before?

And while there’s no single answer, patterns do exist. Especially between melanoma and breast cancer.

Melanoma and Breast Cancer: Is There a Connection?

On the surface, melanoma and breast cancer don’t seem related. One starts in pigment-producing cells of the skin; the other begins in glandular tissue deep inside the breast. Their risk factors are different, their behaviors distinct. But research has found something surprising: people who develop one often have an elevated risk of developing the other.

That link goes both ways. Studies show that women with a history of breast cancer have a slightly increased risk of developing melanoma, and vice versa. The reasons are still being explored. Some of the connection may be environmental — such as shared exposure to UV radiation (from tanning beds or sunbathing) and radiation therapy to the chest. But part of it may be genetic.

When It’s Not Coincidence: The Genetic Angle

A small but significant number of patients carry inherited mutations that raise the risk for multiple cancers. For example, mutations in the CDKN2A gene — often associated with familial melanoma — can also increase risk for pancreatic cancer and, potentially, breast cancer. Other mutations, like BRCA2, are strongly linked to breast and ovarian cancer, but may also play a role in melanoma development, particularly in families with high cancer burdens.

Then there’s BAP1, a tumor suppressor gene that, when mutated, can predispose people to uveal melanoma (a rare eye melanoma), as well as mesothelioma, kidney cancer, and sometimes breast cancer. These aren’t common mutations, but when multiple cancers cluster in one person or family — especially at young ages — genetic counseling becomes a vital part of care.

It’s not just about managing one cancer. It’s about understanding the whole risk profile, and tailoring screening and prevention accordingly.

Melanoma in the Breast — or Two Primary Cancers?

When patients hear “melanoma breast cancer,” it can mean one of two things — and the difference matters.

The first is melanoma metastasizing to the breast. This is rare, but it happens. The breast isn’t a common site of metastasis, but melanoma has been known to appear there, usually as a firm, painless mass. Because of its rarity, it can be mistaken for a primary breast tumor until biopsy confirms its true origin. In these cases, treatment is based on melanoma protocols, not breast cancer guidelines.

The second meaning is having two separate primary cancers — melanoma and breast cancer — either diagnosed together or in close succession. This is more common than metastatic spread. It may reflect shared risk factors, genetics, or just statistical overlap, especially as cancer survivorship improves and people live long enough to encounter more than one malignancy.

Either way, management becomes multidisciplinary. Surveillance intensifies. And the patient’s story shifts from a single diagnosis to a more layered reality.

Shared Surveillance — and What to Watch For

If you’ve had breast cancer, especially if you received radiation to the chest, it’s worth being aware of your skin — not just where the beam landed, but across your entire body. Regular dermatology visits may be recommended, particularly for those with light skin, a history of sunburns, or numerous moles.

Likewise, if you’ve had melanoma, your care team might keep a closer watch on your breast health — especially if you have a strong family history or genetic markers. While melanoma doesn’t directly cause breast cancer, the presence of one may raise vigilance for the other.

None of this is meant to raise fear. It’s about attention. Knowing what you carry — whether it’s a gene, a history, or simply a pattern — lets you catch problems earlier. And when it comes to either melanoma or breast cancer, early detection changes everything.

Part Eight: Living After Melanoma

When the last biopsy comes back clean, or the final dose of immunotherapy is done, there’s a kind of stillness. Not relief exactly — not at first. Just the sudden absence of motion. For weeks or months, your days were filled with appointments, scans, treatment plans, decisions. Then, everything quiets. You’ve made it through. But now what?

Living after melanoma is often more complicated than it looks on the outside. It’s not just about healing scars or finishing treatment. It’s about adjusting to a new kind of attention — one that never fully goes away.

Surveillance Never Really Stops — It Just Changes Shape

If you’ve had melanoma, you don’t graduate from care. You enter a new phase of it — long-term surveillance. For early-stage patients, that may mean skin checks every 6–12 months, annual lymph node exams, and self-monitoring in the mirror at home. For those who had Stage III or IV disease, follow-up often includes regular imaging — PET scans, CTs, sometimes brain MRIs — every few months, at least in the first few years.

Doctors look for local recurrence, new primary melanomas, and distant metastases. And while the chances of recurrence drop over time, the risk never hits zero. Melanoma has a known habit of returning late — sometimes five, ten, even fifteen years later. That doesn’t mean it will. But it explains why dermatologists and oncologists often follow patients for life.

Fear of Recurrence: The Quiet Companion

Even with clean scans and good outcomes, many melanoma survivors live with a low thrum of uncertainty. Every new freckle gets a second look. Every headache raises a question. Some learn to compartmentalize it. Others carry it constantly. It’s not irrational — it’s awareness. And while it can be exhausting, it can also be useful. You don’t have to panic every time something changes. But you do have to notice.

That kind of vigilance is part of life after melanoma. And over time, it becomes less consuming. You learn what’s normal for your skin. You develop a rhythm with your doctors. You start to trust your instincts again — and your body, too.

Physical Recovery and Long-Term Effects

For many, the physical part of recovery is straightforward. A scar fades. Energy returns. But for those who’ve had immunotherapy, the body may not bounce back quite so easily. Some experience fatigue for months. Others develop autoimmune side effects — like thyroid dysfunction, joint pain, or skin issues — that require long-term management. These aren’t always severe, but they’re reminders that treatment doesn’t always stop working just because it’s finished.

If you had a sentinel lymph node dissection or full lymph node removal, you may be at risk for lymphedema — swelling in the arm or leg, especially on the side where nodes were removed. This can be subtle at first and managed with compression, physical therapy, or massage — but it should never be ignored.

And there’s always the possibility of second primary melanomas. Having one melanoma increases your risk of developing another — which is why self-exams and regular derm visits aren’t just about the site of the original tumor. They’re about the whole skin.

Part Nine: Frequently Asked Questions

Can melanoma appear on the ear?

Yes — and it often does. The ear is a high-risk site for melanoma, particularly for men and those with fair skin. It’s frequently exposed to sun but often overlooked in routine self-checks. Melanoma on the ear may look like a discolored patch, a small bump, or a crusted lesion along the rim, behind the ear, or even inside the canal. Because it’s a spot people rarely examine closely, tumors here can grow unnoticed for longer and are sometimes diagnosed at more advanced stages. Dermatologists pay special attention to the ears during full skin exams for exactly this reason.

Is there a blood test for melanoma?

Not at this time — at least not for early detection. Melanoma doesn’t produce a reliable, consistent blood marker like some other cancers do. Standard blood tests won’t detect it. If you’re concerned about a mole or a skin change, only a biopsy can confirm melanoma. That said, in advanced stages of the disease, blood work may include LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) and other markers to help track tumor burden or response to treatment. Researchers are currently exploring blood-based tests like circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) for early-stage detection, but none are ready for routine use yet.

What does early-stage melanoma mean?

Early-stage melanoma typically refers to Stage 0 (in situ) and Stage I disease. In Stage 0, cancer cells are confined to the top layer of skin and haven’t yet invaded deeper tissue — making this stage almost always curable with surgery alone. Stage I melanomas have penetrated into the second layer (the dermis) but remain relatively shallow (under 2 mm), with no signs of lymph node involvement or metastasis. These stages carry high survival rates and usually don’t require systemic treatment beyond surgery. The key is catching them before they go deeper — which is why routine skin checks and early biopsies matter.

What’s the connection between breast cancer and melanoma?

There’s a growing body of research showing that people with breast cancer have a slightly increased risk of developing melanoma, and vice versa. This link may be due to shared genetic risk factors, like BRCA2 or CDKN2A mutations, or to environmental exposures like UV light or prior radiation therapy to the chest. It’s not that one causes the other directly, but they can coexist more frequently than expected. In some cases, genetic counseling may be recommended, especially if multiple family members have had either or both cancers. Screening recommendations might also be adjusted based on this risk overlap.

Can melanoma spread to the breast?

It can — though it’s rare. When people refer to “melanoma breast cancer,” they might mean melanoma that has metastasized to the breast, which is uncommon but possible. The breast is not a typical site of spread, but melanoma is aggressive and can show up in almost any tissue, including the breast, lungs, liver, and brain. If a mass appears in the breast and a person has a history of melanoma, a biopsy is needed to determine whether it’s a new primary breast canceror a melanoma metastasis. The treatment depends entirely on which it turns out to be.

What happens if melanoma spreads to the liver?

If melanoma spreads to the liver, it’s considered Stage IV, or metastatic disease. The liver is one of the more common sites for distant melanoma spread, along with the lungs, brain, and bones. This doesn’t mean treatment stops — but it does mean that systemic therapy becomes the focus. Patients may receive immunotherapy, targeted therapy (if their cancer has a BRAF mutation), or sometimes liver-directed radiation or surgery in very select cases. While liver metastases once carried a very poor prognosis, newer therapies have significantly improved outcomes, and some patients with liver involvement live for years with stable disease.

Closing Thoughts

Melanoma is a skin cancer, but it rarely stays skin-deep. It demands attention not just because of how it starts, but because of where it can go — and how quickly. But for all its reputation, it’s also one of the most studied, most actively treated, and most closely monitored cancers today. Outcomes have improved. Options have expanded. And for many, the difference between danger and survival still comes down to noticing one small change — and acting on it.

Whether you’re here with a diagnosis, a concern, or just a question, that attention is the most powerful thing you carry. Melanoma moves quickly. But so can you.