Stomach Cancer: Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options

- Foreword

- Part One: Understanding Stomach Cancer

- Part Two: Early Symptoms and Warning Signs

- Part Three: Family History and Genetic Risk

- Part Four: Diagnostic Process – Tests and Imaging (Narrative Version)

- Part Five: Staging and Prognosis

- Part Six: Treatment Options Overview

- Part Seven: Surgery

- Part Eight: Chemotherapy for Stomach Cancer

- Part Nine: Radiation Therapy

- Part Ten: Nutritional and Lifestyle Management

- Part Thirteen: Frequently Asked Questions

- Closing Thoughts

Foreword

If you’re here, chances are you’re searching for answers — not just medical facts, but something more personal. Maybe you’re facing a diagnosis, or maybe it’s your parent, your partner, your sibling. Maybe it’s just a lingering worry you haven’t been able to shake. Whatever brought you to this page, you deserve information that speaks to you clearly and honestly, without alarm or sugarcoating.

Stomach cancer doesn’t get as much attention as some other cancers. It doesn’t always show up in flashy headlines. But for the people it touches — and for their families — it’s anything but invisible. It’s real, it’s complicated, and it raises tough questions. What are the symptoms? How is it diagnosed? Could it run in my family? What are the chances of beating it?

This article was written with those questions in mind. It’s long — because the subject deserves time and care. And it’s detailed — because shallow answers don’t help when your health or your loved one’s life is at stake. We’ll walk through everything: symptoms, scans, blood tests, colonoscopies, CT images, chemo options, family risks, and what it means to live with or after a diagnosis. We’ll keep the language grounded and human. No medical jargon unless it’s useful, and always explained when it appears.

Whatever your reason for reading, I hope you find clarity here — and maybe a little peace in knowing you’re not alone.

Part One: Understanding Stomach Cancer

We don’t usually think about our stomach until something goes wrong. Maybe it’s a lingering ache, a heaviness after eating, or just a sense that something’s not quite right. For most people, it turns out to be nothing serious. But for others, that quiet discomfort becomes the first whisper of something much larger: stomach cancer.

If you or someone you love is facing this possibility, you’re not alone. Stomach cancer — also known as gastric cancer — affects hundreds of thousands of people every year worldwide. It often arrives quietly, hiding in symptoms that feel familiar or harmless. That’s part of what makes it such a difficult disease to catch early, and why understanding it matters so much.

So let’s start with the basics — not just the medical facts, but the real story of what stomach cancer is, how it begins, and what kinds of cells it involves. The more you know, the clearer your path forward can become.

What Is Stomach Cancer?

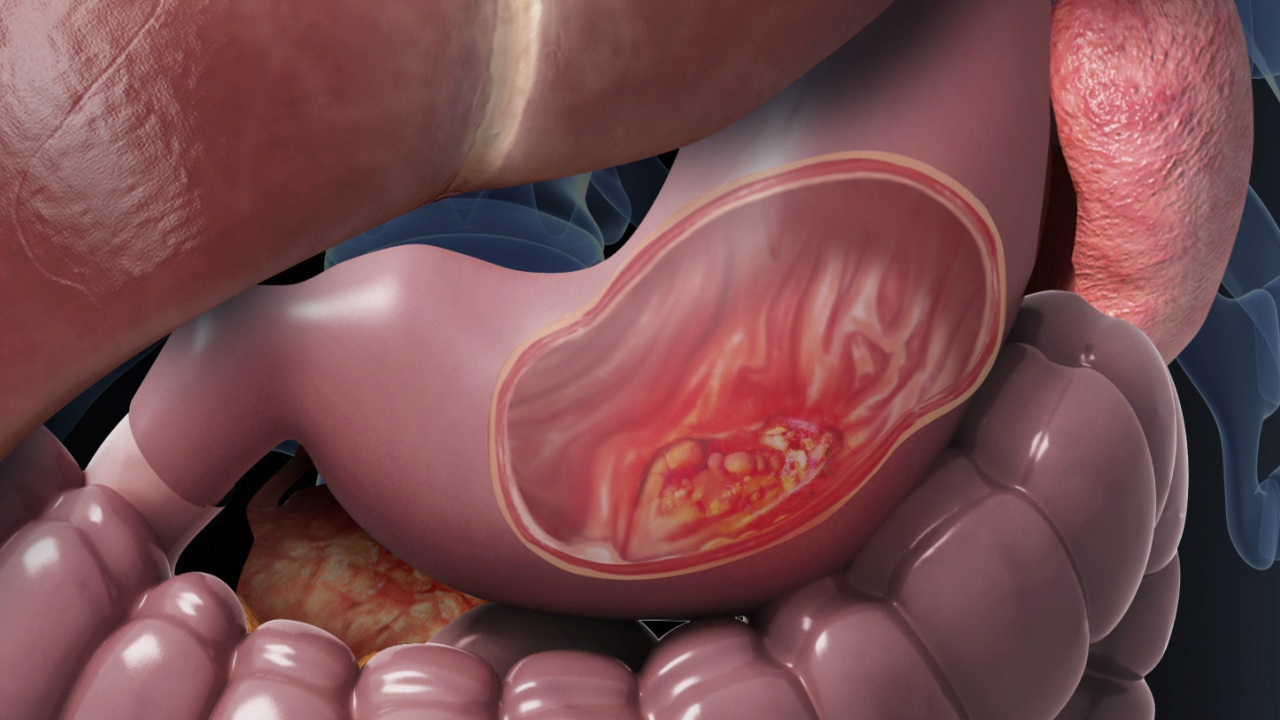

Stomach cancer begins when cells in the stomach lining grow out of control. Most of the time, it starts in the innermost layer — the mucosa — which produces acid and digestive enzymes. From there, the abnormal cells can slowly invade deeper layers of the stomach wall, and eventually spread to lymph nodes or other organs.

The most common type by far is adenocarcinoma, accounting for over 90% of cases. This form arises from the glandular cells that line the stomach’s inner surface. But not all stomach cancers are the same. There are rarer types, too, and each behaves a bit differently:

- Lymphomas begin in the immune cells of the stomach wall.

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) grow from special cells in the stomach’s muscle lining.

- Carcinoid tumors come from hormone-producing cells.

We’ll cover these more in-depth later, but for now, it’s enough to know that when doctors say “stomach cancer,” they usually mean adenocarcinoma — and this is what most treatments are designed to address.

Where It Happens and Why That Matters

The stomach isn’t just one homogenous pouch. It has distinct regions, each with its own role in digestion. Cancer can begin in any part — the cardia (where the esophagus meets the stomach), the body, or the antrum (the lower portion near the small intestine).

Where the tumor starts matters a great deal. For instance, tumors in the cardia (the upper part) behave more like esophageal cancers and may have different risk factors, like long-term acid reflux. Cancers in the lower stomach may be linked more strongly to chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that quietly irritates the stomach lining over many years.

How Common Is Stomach Cancer?

Globally, stomach cancer remains one of the most common and deadly cancers — especially in East Asia, Eastern Europe, and parts of South America. In places like Japan and Korea, it’s so prevalent that routine screening is part of standard healthcare for older adults.

In the United States and many Western countries, it’s less common than it used to be — likely due to improved refrigeration, lower rates of H. pylori infection, and changes in diet. But while the overall incidence has declined, one subset is quietly rising: cardia tumors in younger adults, especially men under 50.

That trend is part of a larger mystery still being unraveled by researchers. We’ll explore it further when we talk about risk factors and genetics, but it’s a reminder that this disease is changing — and that vigilance still matters.

Why It’s Often Missed Early

Unlike cancers that cause sudden, dramatic symptoms, stomach cancer often creeps in slowly. You might feel full after eating small amounts. You might notice nausea, fatigue, or anemia. These signs are easy to dismiss — especially when they overlap with things like ulcers, acid reflux, or everyday stress.

That quiet onset is why many people are diagnosed only when the disease has already advanced. It’s not about ignoring symptoms — it’s about how subtle they can be. That’s also why clear information, routine checkups, and attention to family history can make such a difference.

Part Two: Early Symptoms and Warning Signs

Most people don’t expect stomach cancer. That’s one of the hardest parts. It doesn’t come with an announcement. It doesn’t always show up on routine bloodwork. It’s quiet — and for a while, it can even be invisible.

The earliest signs, when they do appear, are subtle. A little discomfort after eating. A sense of fullness that comes too quickly. Maybe a drop in appetite you chalk up to stress or a busy schedule. And often, people wait — not because they’re careless, but because it doesn’t feel urgent. That’s completely understandable. The body has a hundred little quirks, and most of them come and go. But when symptoms linger, change, or slowly build up in complexity, they can start to draw a line toward something deeper.

Let’s break that line down — carefully, clearly — so you know what to look for, and why these symptoms matter.

The Vague Signals That Often Come First

Stomach cancer rarely bursts into view. It creeps in. That’s why early-stage cases are so often missed. People live with these symptoms for weeks, even months, before realizing they might signal something serious.

Some of the earliest signs include:

- Early satiety — feeling full after eating just a few bites. This happens when a tumor begins to interfere with the stomach’s ability to stretch and accommodate food.

- Mild nausea or bloating — often mistaken for indigestion, especially in people with a history of reflux, gastritis, or IBS. It may come and go at first, but eventually become more consistent.

- General loss of appetite — food becomes unappealing, sometimes without nausea, just a subtle aversion that builds up over time.

- Unexplained fatigue — not always recognized as a stomach symptom. But if there’s slow internal bleeding (even microscopic), iron levels can drop, leading to anemia — and with it, exhaustion that doesn’t improve with rest.

What makes these symptoms so deceptive is how familiar they feel. Who hasn’t experienced indigestion or fatigue at some point? And when symptoms are low-level, they don’t raise red flags — not for the person experiencing them, and sometimes not even for doctors, especially in younger patients.

The Red Flags That Should Never Be Ignored

As stomach cancer progresses, it often becomes more assertive. It starts to interfere with digestion, nutrition, and overall function. At this stage, certain symptoms should always prompt further investigation:

- Persistent or worsening stomach pain — especially if it’s not tied to meals or stress, and doesn’t respond to common treatments like antacids.

- Unintended weight loss — this isn’t just a few pounds. We’re talking about weight loss without dieting, without increased activity, often paired with fatigue and muscle thinning.

- Vomiting — especially if food comes up undigested, or if it contains traces of blood (which may appear red or resemble coffee grounds).

- Black or tarry stools (melena) — a sign of bleeding in the upper digestive tract. Even small, slow bleeds can lead to long-term blood loss and anemia.

- Persistent anemia — if blood tests show chronic low iron or hemoglobin without a clear cause, your doctor should always rule out gastrointestinal sources, including stomach cancer.

Symptom Overlap: The Diagnostic Fog

Many of these symptoms — nausea, reflux, fatigue, anemia — overlap with common benign conditions. Ulcers, H. pyloriinfection, gastritis, and even food intolerances can produce similar discomforts. This overlap is why stomach cancer can so easily hide in plain sight.

Let’s take ulcers, for instance. They often cause pain after meals, bloating, and occasional nausea — all things you might also see in early-stage cancer. In some cases, a tumor even erodes into the stomach lining, creating something that looks like an ulcer on imaging. That’s why biopsies during endoscopy are so essential. A visual exam isn’t enough — you need tissue confirmation.

Or take iron-deficiency anemia, especially in menstruating women. It’s easy to assume the cause is gynecological. But in men, and in women after menopause, anemia should always raise suspicion for occult GI bleeding — especially if it doesn’t respond to supplementation.

Even appetite loss and weight loss — two classic cancer indicators — can be written off as stress, depression, or dietary changes. That’s why timing matters. Duration matters. Patterns matter. A single vague symptom might not point anywhere. But several symptoms, sustained over weeks or months, begin to trace a pattern — one that deserves attention.

Symptom Progression by Cancer Location

The stomach isn’t a uniform space. Tumors in different areas can cause different symptoms.

- Cardia (upper stomach): When tumors grow near the junction with the esophagus, they can mimic esophageal cancer. You might feel food sticking, or develop trouble swallowing (dysphagia). These cancers are often linked to chronic GERD.

- Body (middle stomach): These tumors tend to grow silently until they interfere with digestion. They’re less likely to cause early symptoms and more likely to present at a later stage.

- Antrum (lower stomach): Tumors here may delay stomach emptying, leading to bloating, early fullness, and vomiting. They also tend to bleed more easily, contributing to anemia.

The point isn’t to self-diagnose based on location — that’s impossible without imaging and biopsy. But understanding how location shapes symptoms can help guide what questions to ask and what follow-ups to request.

When Should You Worry?

This is the question that haunts many people, especially if cancer runs in the family or if symptoms have been brushed off before.

Here’s a good rule of thumb: any digestive symptom that lingers beyond a few weeks, worsens over time, or resists standard treatment deserves further investigation. And if that symptom comes with fatigue, weight loss, or anemia — even more so.

Even if the outcome is something benign — and in many cases, it is — the cost of missing a diagnosis far outweighs the inconvenience of asking for tests.

A Note to the Reader

It’s okay to be unsure. It’s okay to hesitate. But if something in your body feels off — if the symptoms you’re reading about sound a little too familiar — it’s worth talking to someone. That doesn’t mean panicking. It just means paying attention. You don’t need to have answers right away. You just need to take the first step toward finding them.

Part Three: Family History and Genetic Risk

There’s a particular kind of worry that doesn’t go away after a checkup. It comes when someone you love — maybe your mother, your father, your sibling — hears the word “cancer” in a doctor’s office. That moment plants a question that can linger for years: What does this mean for me?

When it comes to stomach cancer, that question is real, and it deserves honest answers. While most cases happen sporadically, without a clear inherited cause, there are families where the pattern is too strong to ignore. And in some of those families, the risk isn’t just a vague possibility — it’s written into the genes.

So what happens when a sibling is diagnosed? Should you be screened earlier? Could a colonoscopy help? Is there a genetic test? Let’s walk through it.

Does Stomach Cancer Run in Families?

Yes — but not always in the way people think.

Most stomach cancer cases are not inherited. They result from a combination of environmental exposures, infections (especially H. pylori), diet, and chance mutations over time. That said, about 10% of cases show some form of familial clustering. And within that group, a smaller subset — about 1–3% — are clearly hereditary, caused by identifiable gene mutations passed from parent to child.

What Counts as a Family History?

Family history isn’t just one case in a distant relative. It carries more weight when the cancer occurred:

- In a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child)

- At a young age (typically before 50)

- In multiple family members, across generations

- Alongside other related cancers, like breast, colon, or ovarian

For example, if your brother was diagnosed with stomach cancer at 45, and your mother had breast cancer at 50, that may suggest a hereditary syndrome — not just bad luck.

Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (HDGC)

The most well-studied genetic cause of stomach cancer is Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer (HDGC), a syndrome linked to mutations in the CDH1 gene.

People with this mutation are at high risk for a rare, aggressive form of cancer called diffuse-type gastric cancer. This type doesn’t form a single, solid tumor. Instead, cancer cells scatter across the stomach lining, often making it hard to detect until it’s advanced.

For people who test positive for the CDH1 mutation, the lifetime risk of stomach cancer can exceed 70% — which is why some patients opt for preventive total gastrectomy (surgical removal of the stomach) even before symptoms begin.

HDGC is also linked to lobular breast cancer, so families affected by this mutation may have both gastric and breast cancers in their history. Genetic counseling is essential in these cases, and testing is often recommended for multiple family members.

Lynch Syndrome and Other Genetic Conditions

Other hereditary syndromes, while not as stomach-specific, can increase gastric cancer risk as part of a broader pattern:

- Lynch syndrome (HNPCC): Most famous for its link to colon cancer, but also raises the risk of stomach, small bowel, and endometrial cancers. Caused by mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes (e.g., MLH1, MSH2).

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): Known for colon polyps and colon cancer, but also linked to stomach and duodenal polyps, especially in the upper GI tract.

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: Rare, but can involve multiple cancers, including gastric.

If you have a strong family history of mixed cancers, or if relatives have been diagnosed unusually young, a genetics team can help piece the puzzle together.

If a Sibling Has Stomach Cancer, Should You Be Screened?

Now we come to one of the most practical questions: What if my sibling was diagnosed — should I get checked sooner?

The short answer is: yes, but with a tailored approach.

There’s no universal guideline that says everyone with an affected sibling needs immediate screening. But most doctors agree that first-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients — especially those diagnosed before age 50 — may benefit from early endoscopy, particularly if:

- You also have digestive symptoms (e.g., anemia, reflux, weight loss)

- Your sibling had diffuse-type cancer, or tested positive for a mutation

- There’s a family history of gastric cancer in more than one person

Even in the absence of symptoms, screening endoscopy might be considered as early as age 40, or 10 years before your sibling’s diagnosis. This allows for detection of precancerous changes like intestinal metaplasia or atrophic gastritis, both of which can be monitored or treated.

Can a Colonoscopy Help?

This is where things get a little more nuanced. A colonoscopy is a powerful tool for detecting colorectal cancer, but it does not examine the stomach. So, in a direct sense, no — it doesn’t detect stomach cancer.

However, if your sibling had Lynch syndrome or another hereditary condition that affects both the stomach and colon, a colonoscopy might be part of a broader screening plan. It’s not a substitute for upper endoscopy (gastroscopy), but it may still be relevant depending on your family’s history and genetic findings.

To put it simply:

- Colonoscopy = colon

- Endoscopy = stomach If you’re concerned about stomach cancer specifically, you’ll need an upper GI evaluation.

What About Blood Tests?

People often ask: Is there a blood test to screen for stomach cancer? Not reliably.

Some blood markers — like CEA or CA 19-9 — can be elevated in gastric cancer, but they are not specific. They don’t detect early disease, and they can be high in many non-cancerous conditions. Their primary use is in monitoring treatment response, not early detection.

That said, if your blood work shows chronic unexplained anemia, it could be a subtle clue. In that case, doctors often order an endoscopy to look for slow bleeding in the stomach or upper intestines.

Takeaways for Families

If someone close to you has had stomach cancer, your risk may be slightly higher — and in some cases, significantly higher. But risk isn’t destiny. It’s a signal. One that tells you to stay alert, to ask questions, and to advocate for screening when your gut tells you something isn’t right.

Family history is a story written across generations. The more you know about that story — who had what, and when — the better equipped you are to shape your own.

Part Four: Diagnostic Process – Tests and Imaging (Narrative Version)

The moment symptoms become persistent — not dramatic, just steady and quietly unsettling — the question arises: what’s really going on? The body doesn’t hand over answers freely, especially with a disease like stomach cancer. It has to be investigated, uncovered layer by layer, often with a combination of tools that each reveal a different part of the story.

Let’s begin with a common misconception. Many people assume that a colonoscopy, being one of the most well-known cancer screening tests, might help detect stomach cancer too. It makes sense intuitively — the gastrointestinal system is all connected, right? But in practice, colonoscopy only examines the colon and rectum. It goes up from the bottom, not down from the throat, and stops well short of the stomach. So no — it doesn’t detect stomach cancer directly. If the concern is higher up, in the stomach itself, the test you need is called an upper endoscopy.

Upper endoscopy — or gastroscopy — involves passing a thin, flexible tube down the throat to visually inspect the stomach lining and, most importantly, to take biopsies. This is the gold standard. If there’s a visible lesion, a suspicious thickening, or even a spot that just doesn’t look quite right, the scope allows the doctor to sample tissue on the spot. That tissue, when examined under a microscope, is what confirms whether cancer cells are present. There’s no guesswork at this stage — diagnosis means cells have been seen and identified.

Of course, many people still ask: can’t a blood test catch it sooner? Wouldn’t that be easier? It would — but the truth is, blood tests don’t work well for detecting stomach cancer early. There are no reliable screening markers like there are for prostate or liver cancer. Certain proteins, like CEA or CA 19-9, can rise in some patients with gastric cancer, but they’re inconsistent. They don’t show up in all cases, and they’re not exclusive to cancer — they can be elevated in a range of benign conditions too. So they’re sometimes helpful after diagnosis, for tracking how treatment is going, but they’re not useful for finding cancer in the first place.

That said, blood work can still offer subtle clues. Chronic iron deficiency, for instance, can be an early warning sign — especially if there’s no clear reason for it. A stomach tumor can bleed slowly over time, not enough to cause visible blood in stool, but enough to drain your iron stores and cause fatigue. When anemia turns up without a known cause, particularly in older adults or postmenopausal women, doctors often order an endoscopy just to be safe.

Once a diagnosis is made — once cancer is confirmed through biopsy — the question changes. It’s no longer “is this cancer?” but rather, “how far has it gone?” That’s when imaging steps in. A CT scan is usually the first choice, because it offers a wide, detailed view of the abdomen and chest. It can show whether the tumor has invaded nearby organs, whether lymph nodes are enlarged, or whether metastases have formed in the liver or lungs. When people look up stomach cancer CT images, what they often find are scans showing a thickened stomach wall or irregular masses — the radiological signature of disease that’s moved beyond the surface.

Other scans add nuance. Endoscopic ultrasound can be used to determine how deep the tumor has grown into the stomach wall and whether the nearby lymph nodes are involved — information that can guide surgeons on whether the cancer might be curable with surgery. A PET scan might follow if there’s concern about distant spread, especially to places not easily seen on a regular CT. And while MRI is less commonly used, it can sometimes help clarify details in the liver or if contrast agents can’t be used due to kidney problems.

So the diagnostic process is not a single moment. It’s a chain of moments — suspicion, bloodwork, endoscopy, biopsy, imaging — each one filling in part of the picture. Some people go through this process quickly, in just a few days. Others spend weeks moving from test to test, waiting for answers to come back, trying to understand what’s been found and what it means. That waiting can be agonizing. But every test is a step forward, even the ones that rule things out.

If you’re in this process now — watching a loved one go through it, or navigating it yourself — know that it’s okay to ask for clarity. Ask why a certain scan is being ordered. Ask what the next step is. If you’ve had symptoms for a while and your tests aren’t showing much, it’s okay to press for more. Sometimes stomach cancer hides behind normal labs and vague discomfort. Sometimes the only thing that finds it is persistence.

And that’s really the heart of this part of the story. Diagnosis isn’t just about technology. It’s about listening closely to a body that’s been trying to say something — and finally finding the tools to hear it clearly.

Part Five: Staging and Prognosis

After the diagnosis comes the next, heavier question: how far has it gone? And often, that question feels bigger than the answer. It’s not just about what stage the cancer is labeled with. It’s about what’s still possible — surgery, remission, more years, a plan. But before those decisions can be made, doctors need to understand the full shape of the disease. That’s what staging is for.

Staging doesn’t measure how sick you feel. It doesn’t even measure how “bad” the cancer is in some emotional sense. It measures structure: how deeply the tumor has grown into the stomach wall, whether it’s reached the lymph nodes, whether it’s moved outside the stomach altogether. Every decision that follows — which treatments are offered, in what order, with what intent — rests on that framework.

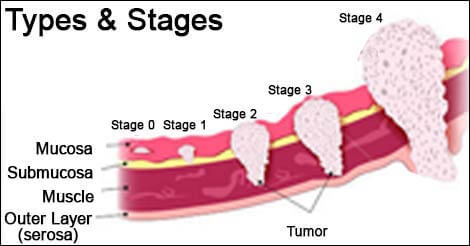

Doctors use something called the TNM system, which stands for Tumor, Nodes, and Metastasis. It sounds clinical, and it is, but it can be understood in plain terms. The “T” stage describes how far the tumor has pushed into the stomach wall. The wall isn’t a single sheet — it has layers, like skin or bark. Some tumors stay near the surface for a long time; others dig deep. If the tumor is still confined to the inner lining, it’s a T1. If it’s burrowed all the way through to the outer layer, it might be T4.

Then come the lymph nodes — the “N” in TNM. The stomach is surrounded by dozens of lymph nodes, little checkpoints where immune cells scan for trouble. Cancer often spreads here first, and doctors will want to know how many nodes are involved, and how far from the original tumor those nodes are located. Just one or two nodes might still mean the cancer is curable. A larger cluster may suggest it’s already on the move.

The last letter — “M” — stands for metastasis. Has the cancer left the neighborhood entirely? Has it reached the liver, lungs, or distant lymph nodes? If so, that usually places the cancer at Stage IV, and the focus of treatment shifts. Not away from hope, necessarily, but away from cure — and toward control, relief, and time.

Most patients will hear their stage described as a number between I and IV. That number wraps up the TNM details into something simpler. Stage I typically means the tumor is small, shallow, and contained. Stage II or III might involve deeper invasion or spread to local nodes. Stage IV means distant spread. But these labels, while helpful for sorting treatment options, don’t dictate individual outcomes. People with stage III disease have sometimes lived longer than people with stage II. Biology doesn’t always behave according to paper rules.

This is where prognosis enters the conversation — and where it gets more delicate. Many people want to know, quietly or directly: what are my chances? But prognosis is not a single number. It’s a range, built from data, not from destiny. Studies might say that five-year survival for early-stage stomach cancer is high — as much as 70% or 80% if caught early and fully removed. Later-stage cancers have lower numbers, and metastatic cases are more challenging still. But even these numbers bend depending on the tumor’s type, how it responds to chemo, the surgeon’s skill, the patient’s overall health, and sometimes pure biological chance.

For example, diffuse-type gastric cancer, which spreads more like a mist through the stomach lining than as a distinct lump, tends to be more aggressive and harder to spot early. It behaves differently from intestinal-type cancer, which is more localized and often found at a resectable stage. HER2 status, microsatellite instability, and other molecular features can also shift the landscape, sometimes dramatically, especially as targeted therapies evolve.

All of this means that staging is essential — but never the whole story. It gives you a map, not a sentence. And like any map, it tells you where you are, but not how far you’ll go, or how you’ll travel.

One more thing to know: staging can change over time. The clinical stage is based on scans and endoscopy before treatment. But once surgery is performed, doctors can examine the tumor and nodes under a microscope and assign a pathological stage — often more accurate, and sometimes different. And if treatment comes first — like chemotherapy to shrink the tumor before surgery — the staging may be reassessed again afterward, depending on how the cancer responded.

It’s a lot to absorb. But when you’re sitting with this information, it helps to remember that staging is not meant to overwhelm. It’s there to guide. Whether it points to surgery, chemotherapy, or simply the next conversation, it marks the beginning of something more structured — a shift from uncertainty into action.

Part Six: Treatment Options Overview

Once the stage is clear, the conversation shifts again — from classification to action. This is where treatment begins. But before you get to the details — chemo regimens, surgery plans, radiation doses — it’s important to understand the goals behind them. Because not every treatment is aimed at the same outcome. Some aim to remove the cancer entirely. Some aim to shrink it, slow it down, or relieve what it’s causing. Some try to do all of that at once.

So the first and most important question in treatment planning is this: Is this cancer potentially curable, or is the goal to control it for as long and as well as possible?

That answer depends on many things — stage, tumor location, patient health, and how the cancer responds to early treatments. But the distinction matters, because it shapes the entire approach.

In curative cases, especially in stages I through III, treatment usually starts with the assumption that the cancer can be removed — either immediately, or after shrinking it with chemotherapy. The stomach, or part of it, can be surgically taken out. The surrounding lymph nodes can be dissected. Chemo or radiation may be used before or after surgery to reduce the risk of recurrence. The goal is long-term survival. Ideally, cure.

In non-curative (palliative) cases, especially at stage IV, the cancer has spread beyond what surgery can safely remove. But treatment doesn’t stop. It changes focus. Instead of trying to eliminate every cell, the aim becomes controlling the disease — keeping it from growing, relieving symptoms, and preserving quality of life. Here, chemotherapy still plays a major role, sometimes alongside targeted drugs or immunotherapy, and sometimes with procedures designed to ease pain, restore appetite, or open blockages in the digestive system.

For some people, treatment follows a neoadjuvant pathway — that means chemo is given first, before surgery, to shrink the tumor and address micrometastatic disease. Others may go straight to surgery and then receive adjuvant therapy — chemo, and sometimes radiation, to catch any stray cancer cells left behind. These sequences are carefully chosen based on staging and tumor biology.

And then there are cases that don’t fit neatly into either box. Some patients begin with a palliative plan but respond so well that surgery becomes possible. Others begin on a curative path, only to discover during surgery that the cancer has spread more than expected. In real life, treatment doesn’t always follow a clean script. Plans adjust. That’s why care is almost always coordinated by a multidisciplinary team — surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, dietitians, and often palliative specialists working together to map out next steps.

There’s also the patient’s own health and resilience to consider. Stomach cancer treatments are demanding. Major surgery, months of chemo, nutritional disruption — these things take a toll. So doctors weigh not just what’s theoretically possible, but what’s realistically safe and meaningful for the person sitting in front of them. A treatment that offers a five percent improvement on paper might not be worth it if it means months of misery for someone already frail. These choices are personal, not mechanical.

And then, of course, there’s time. Time to prepare, time to recover, time to decide. Not every treatment has to begin the same week the diagnosis is made. Often, there’s room to think, ask questions, gather second opinions, and understand what each path will look like before choosing it. That’s part of treatment too — the decision-making, the pacing, the agency.

So this is the framework. In the next sections, we’ll walk through each major component — surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapy, nutrition, and supportive care — in full depth. But before we do, let this be the core idea: stomach cancer treatment is not just about attacking the disease. It’s about coordinating care that fits the person, the tumor, the goals, and the reality of life as it’s being lived.

Part Seven: Surgery

If the cancer is caught early enough, and if it hasn’t spread too far, surgery becomes the central tool in trying to remove it entirely. For many patients, this is the turning point — when the possibility of cure comes into focus. But surgery for stomach cancer isn’t small. It’s not a quick in-and-out procedure. It changes anatomy, appetite, and sometimes the way life feels every day. That’s why deciding on surgery is about more than just eligibility. It’s about readiness — physically, nutritionally, psychologically.

So what does surgery actually involve? And what happens afterward?

Types of Surgery for Stomach Cancer

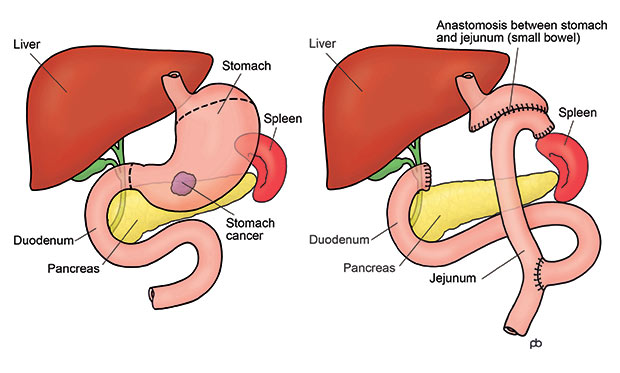

Most patients who undergo surgery will have either a partial gastrectomy or a total gastrectomy. The choice depends on where the tumor is located and how much of the stomach is affected.

When the tumor sits in the lower part of the stomach, surgeons can often remove just that portion — this is a partial gastrectomy. They’ll reconnect the remaining part of the stomach to the small intestine, often using a loop of bowel to create a new passage for food. When the tumor is higher up, near the junction with the esophagus, or if the cancer is more widespread across the stomach lining, a total gastrectomy may be required. In this case, the entire stomach is removed, and the esophagus is directly attached to the small intestine.

Neither approach is easy, but both are survivable. People live without a stomach. The body adapts. Eating becomes different — smaller meals, more frequent meals, more attention to nutrients — but not impossible. In time, many patients return to a full range of eating experiences, albeit with a new rhythm and more awareness of their body’s signals.

Lymph Node Dissection: Why It Matters

During either surgery, the surgeon will also remove a number of lymph nodes from around the stomach. This is called a lymphadenectomy, and it’s just as important as removing the tumor itself. Cancer cells often spread first to these nearby nodes, and examining them under the microscope helps doctors understand the full extent of the disease.

The number of nodes removed matters. The more that are examined, the more accurate the staging will be. In some countries, especially in Asia, surgeons routinely remove 15 or more nodes as part of a standard D2 dissection. This has been shown to improve long-term survival when done safely by experienced surgeons. In other regions, such as the U.S., practices vary depending on institutional experience and individual anatomy.

Minimally Invasive vs Open Surgery

In many specialized centers, laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgery is now an option. These methods use smaller incisions and camera-guided instruments to perform the same operation with less trauma to the body. Recovery may be faster, and hospital stays shorter. But minimally invasive techniques are not suitable for every case. Large tumors, extensive nodal disease, or certain body types may still require open surgery.

The key is not just the technique — it’s who’s performing it. Gastric cancer surgery is complex, and outcomes are often better when done by high-volume surgeons in high-volume centers. Experience matters, especially when the margins are tight.

What Recovery Looks Like

Recovery isn’t just about healing the incision. It’s about adjusting to a new digestive system. After surgery, most patients spend several days in the hospital. Pain is managed carefully. Fluids come first, then clear liquids, then soft foods. It’s a slow progression, and everyone moves through it at their own pace.

The most common early issues include nausea, bloating, and a sensation of fullness after very small meals. Some patients experience what’s called dumping syndrome — a rapid shift of food into the intestine that causes cramping, lightheadedness, or diarrhea. It’s unpleasant, but manageable with dietary adjustments.

Over the first few months, weight loss is expected. The appetite changes. Food moves faster. Absorption may be less efficient, especially for nutrients like vitamin B12, iron, calcium, and folate. Patients often need supplements, and regular monitoring becomes part of the new routine.

But the human body is remarkably adaptable. Many people — even after a full gastrectomy — learn to eat normally again, just in smaller portions and more often. Meals become mindful. Preferences shift. The relationship with food becomes more intimate, sometimes more appreciative.

When Surgery Isn’t the First Step

Not every case goes straight to the operating room. If the tumor is large, or there’s clear nodal spread, doctors may recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy first. The goal is to shrink the tumor, kill micrometastatic disease, and increase the chances of a clean surgical margin. After several cycles of chemo, imaging is repeated. If the tumor has responded well and hasn’t spread further, surgery is scheduled.

In other cases, surgery may come later — or not at all. If staging scans reveal distant metastases, removing the stomach won’t cure the disease. In those cases, the focus turns to systemic treatment, and surgery may only be done to relieve symptoms like obstruction or bleeding.

A Decision That Reshapes the Body — and the Path Forward

Surgery for stomach cancer is more than a physical intervention. It’s a turning point — a moment when the disease is confronted head-on. For some, it’s the first major step in a long recovery. For others, it’s part of a broader strategy that includes chemotherapy and careful monitoring. Either way, it marks a shift: from waiting and wondering to acting.

And that shift — even when it’s scary, even when it’s exhausting — is often where hope starts to feel real again.

Part Eight: Chemotherapy for Stomach Cancer

Chemotherapy has a complicated reputation. For some, it represents the most aggressive part of treatment — the phase people dread. For others, it’s the best shot at keeping cancer from coming back, or at slowing it down once it spreads. And for many, it’s both at once: difficult, but necessary. Draining, but essential.

In stomach cancer, chemotherapy plays a major role — not just in advanced disease, but in potentially curable cases as well. It can come before surgery, after surgery, instead of surgery, or even later when the goal is purely to relieve symptoms and prolong life. The form it takes depends on the cancer’s stage, biology, and how your body handles treatment.

Let’s walk through what chemotherapy really looks like for stomach cancer patients — when it’s used, what it involves, and how people cope with it over time.

When Chemo Comes First

In many cases, especially when the tumor is large or there are signs that nearby lymph nodes are involved, doctors will recommend neoadjuvant chemotherapy — chemo that comes before surgery. The idea is simple but powerful: attack the cancer systemically before removing it surgically. This helps shrink the tumor, improve the chances of getting clean margins, and eliminate cancer cells that may already be traveling elsewhere in the body but aren’t yet visible on scans.

This approach is now standard in many treatment centers. It’s backed by data. Studies have shown that patients who receive pre-operative chemo often have better long-term outcomes than those who go straight to surgery, especially in stages II and III. After several cycles — usually two to four months of treatment — the tumor is re-evaluated with imaging, and if it has responded, surgery follows.

If surgery goes well and pathology shows that some cancer cells may still remain, additional chemotherapy — adjuvant chemotherapy — may be given afterward to reinforce the effect and reduce the risk of recurrence.

When Chemo Is the Main Treatment

In cases where surgery isn’t possible — either because the cancer has spread to distant organs or because the patient’s health makes surgery too risky — chemotherapy becomes the backbone of treatment. Here, the goal is not to cure, but to control. The right chemo regimen can stop the tumor from growing, ease pain or nausea, and extend survival in a meaningful way. It’s not just about time — it’s about quality of time.

This kind of treatment can continue for many months or even years, depending on how the cancer responds and how well the patient tolerates it. Scans are done every few months to monitor progress. When one combination of drugs stops working, another may be tried. Some patients move between regimens more than once.

What Drugs Are Used?

Stomach cancer doesn’t have a single chemo formula. Treatment usually involves a combination of drugs, chosen based on factors like tumor subtype, stage, and patient health.

Some of the most commonly used drugs include:

- Fluorouracil (5-FU) or its oral version capecitabine, which interfere with cancer cell DNA

- Platinum-based drugs like cisplatin or oxaliplatin, which damage DNA and slow division

- Docetaxel or paclitaxel, which disrupt cell division

- Irinotecan, used in some second-line settings

Often, two or three of these drugs are given together in cycles, spaced every two or three weeks. This is known as combination chemotherapy, and it’s used because stomach cancer tends to be aggressive — and single-drug treatments usually aren’t enough.

For cancers that express HER2, a growth factor receptor, doctors may add a targeted therapy called trastuzumab(Herceptin). This drug locks onto the HER2 receptor and helps slow the growth of tumors that depend on it. Testing for HER2 is now standard in all newly diagnosed metastatic cases.

There’s also a growing role for immunotherapy, especially in patients with high PD-L1 expression, microsatellite instability (MSI-high) tumors, or other biomarkers. Drugs like nivolumab or pembrolizumab, which unleash the immune system’s T-cells to fight cancer, are now approved in some settings and may become more common in the years ahead.

Side Effects and What to Expect

Chemotherapy affects not just cancer cells, but fast-growing cells throughout the body — which is why side effects can be so widespread. Fatigue is common, sometimes constant. Nausea and vomiting can usually be controlled with medication, but still take a toll. Appetite often drops. Hair may thin or fall out. Blood counts fluctuate — lowering immunity, increasing bruising, and causing anemia.

Some patients develop neuropathy — tingling or numbness in the hands and feet — especially with oxaliplatin. Others notice changes in taste, mouth sores, or trouble swallowing. These effects vary widely from person to person, and they don’t always line up neatly with lab values. One person may sail through six rounds with few complaints. Another may struggle after two. It’s unpredictable — and that’s why regular monitoring is essential.

Doctors watch carefully. Blood tests are done before every cycle to check kidney function, liver enzymes, white cells, platelets. If toxicity builds up, doses may be adjusted. Sometimes treatment is paused to let the body recover. The goal isn’t to push patients to the brink — it’s to find the strongest, safest rhythm their body can tolerate.

How People Cope — and Keep Going

No one adjusts to chemo in a single day. It’s a process, physically and emotionally. Some people find their groove quickly — a certain time of day they feel best, a comfort food that still tastes right, a friend who checks in before every session. Others stumble through fatigue and frustration, unsure how to make the days feel normal again.

Support matters here. Oncology nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, social workers — they’re part of the team for a reason. They can help with symptoms, nutrition, medication side effects, and just listening when things feel harder than expected. Palliative care — often misunderstood as end-of-life care — can also play a major role in managing pain, energy levels, and mood, even early in the process.

And over time, people adapt. They learn how their body responds. They build routines around treatment days. They make space for recovery. For some, chemo becomes a kind of rhythm — harsh, but familiar. Something to endure, yes, but also something that keeps a fragile kind of hope alive.

Part Nine: Radiation Therapy

Radiation isn’t always part of the stomach cancer journey. But when it is, it usually enters with a specific purpose — not to replace surgery or chemo, but to complement them, or to relieve symptoms that other treatments can’t fully reach. It’s a focused tool. And like all tools in oncology, its value depends entirely on when, how, and for whom it’s used.

In stomach cancer, radiation has a more limited role than in cancers like breast, prostate, or even esophagus. But that doesn’t mean it’s minor. For certain patients, it plays a key role in increasing survival, easing discomfort, or preventing complications that could interfere with nutrition and quality of life.

So how does it actually work? And when does it make sense?

What Radiation Therapy Does — and Doesn’t Do

Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams — most commonly X-rays — to damage the DNA of cancer cells. The idea is to target the tumor or the area where it was removed, without affecting too much healthy tissue around it. Unlike chemotherapy, which circulates through the whole body, radiation is local. It works where it’s aimed.

This makes it ideal for situations where cancer is confined to a specific area — or where symptoms are coming from one particular spot. It’s not usually effective for treating widespread or metastatic disease, but when there’s a dominant lesion causing bleeding, pain, or obstruction, radiation can provide powerful relief.

When Is Radiation Used in Stomach Cancer?

There are a few key scenarios where radiation might be offered:

1. After surgery (adjuvant therapy):

If the cancer was removed but the margins were close — meaning the tumor extended right up to the edge of the tissue — or if a lot of lymph nodes were involved, radiation may be recommended after surgery along with chemotherapy. The goal here is to kill any microscopic cells left behind in the surgical area and reduce the risk of recurrence.

This approach is more common in the U.S. than in East Asian countries, where surgical lymph node removal is often more extensive. But in centers where fewer nodes are removed or where the tumor was advanced, adjuvant radiation can add an extra layer of protection.

2. When surgery isn’t an option:

If the tumor can’t be removed — either because it’s too large, too entwined with other organs, or the patient isn’t well enough for surgery — radiation may be used with chemotherapy to shrink the tumor and control symptoms. This is often part of a definitive chemoradiation strategy, especially if the cancer is localized but inoperable.

3. For palliative relief:

In advanced cases, where cancer has spread or recurred, radiation can help relieve pain, stop bleeding, or open up areas of the stomach or intestines that are being compressed. These are palliative doses — lower than curative doses — designed to make life more manageable and reduce the burden of symptoms.

How Radiation Is Given

Most patients receive external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). That means the machine stays outside the body and aims high-energy rays precisely at the tumor site. Treatments are delivered in short sessions, usually five days a week, over a period of four to six weeks for curative plans — or fewer sessions for palliative care.

Planning is essential. Before the first treatment, patients go through a simulation session, where a CT scan is used to map the body and define the exact area to be targeted. Tiny skin marks or tattoos may be used to align the body precisely each day. This accuracy helps protect nearby organs, especially the liver, kidneys, and spinal cord.

In recent years, techniques like IMRT (Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy) have made it possible to shape the radiation dose more precisely — delivering high doses to irregular tumor shapes while sparing nearby tissue. This is particularly useful in stomach cancer, where the anatomy is complex and the stomach sits close to many sensitive structures.

What It Feels Like to Go Through It

The actual radiation treatment is painless. It feels like lying still on a hard table while a machine moves around you. The sessions are short — often just 15 to 20 minutes — and there’s no radioactive residue afterward. You’re not glowing. You’re not dangerous to others. You can go home and be with your family.

But over time, side effects build. Most patients develop fatigue, which can feel different from the tiredness of chemo — more like a deep, persistent drain that lingers through the day. There may be nausea, especially if the stomach or surrounding digestive organs are in the field of radiation. Some people experience diarrhea or abdominal cramping. The appetite may shrink. The skin over the treated area can become dry or irritated, though this is usually mild compared to other cancers.

Long-term side effects are possible too — such as mild scarring, reduced stomach capacity, or changes in how food moves through the GI tract — but these vary greatly by dose, area, and whether surgery was also performed.

What helps most during radiation is routine. The daily rhythm — waking up, going in, coming home — creates a sense of structure. Supportive medications are available for most side effects, and dietitians often help adjust eating patterns to minimize discomfort.

Radiation as a Piece of the Whole

Radiation isn’t always offered, and it’s not needed for every case. But when it is used, it’s part of a broader strategy — a complement to surgery, a partner to chemo, a relief valve for pain or pressure. It doesn’t work in isolation. It works because it’s paired with a team that knows when to use it, and why.

Some patients only need it once. Others return to it later, if symptoms reappear. Some never need it at all. But for those who do, it’s one more way medicine bends light — quite literally — toward fighting what the body can’t fight alone.

Part Ten: Nutritional and Lifestyle Management

When people talk about stomach cancer, they often focus on the cancer itself — the surgery, the chemo, the scans. But for many patients, it’s what comes after those treatments that defines daily life. Because whether you’ve had a partial gastrectomy, a total gastrectomy, or just months of chemotherapy, one thing becomes clear very quickly: eating is no longer automatic.

The stomach isn’t just a container. It’s an active organ — stretching, churning, regulating the release of food into the intestine. Without it, or with part of it gone, the body doesn’t lose the ability to digest food, but it does lose the ability to do it in the same way. Meals become smaller. Hunger cues change. Energy comes in waves. And the simple act of eating — something most of us have done without thinking for our entire lives — becomes something new to learn.

Life Without a Stomach — What Changes

If the entire stomach has been removed, the most noticeable change is in portion size. Without a pouch to hold a meal, food passes directly from the esophagus into the small intestine. That means even small meals can feel sudden or overwhelming. It takes time to learn what feels comfortable, what triggers symptoms, and what rhythms the body prefers.

The first few weeks after surgery are usually the hardest. Patients often start with liquids, then soft foods, then small solids. Even when digestion is technically working, symptoms like nausea, bloating, or cramping can make meals difficult. Some people experience dumping syndrome, where food enters the small intestine too quickly and causes a rush of fluid, leading to dizziness, sweating, or diarrhea. Others feel full after just a few bites, or need hours to recover between meals.

But with time, most people adjust. They learn to eat slowly, chew thoroughly, and listen to what their body tolerates. They break meals into five or six small portions a day. They keep snacks nearby. They learn which foods give them steady energy and which ones leave them feeling drained or queasy.

And eventually, eating becomes more natural again — not like before, but familiar enough.

Nutrient Deficiencies and Supplements

When the stomach is altered or removed, the body’s ability to absorb certain nutrients drops — not because food isn’t eaten, but because the environment has changed. The stomach plays a role in absorbing iron, calcium, vitamin B12, and folate, among others.

Vitamin B12 is a particular concern. The stomach produces a protein called intrinsic factor, which is essential for absorbing B12 in the intestine. Without it, even a diet rich in B12 can’t prevent deficiency. That’s why patients who’ve had a total gastrectomy almost always need B12 injections or high-dose sublingual supplements for life.

Iron deficiency is also common, especially if the part of the stomach that helps convert dietary iron is gone. Combined with blood loss from surgery or chemo, this can lead to chronic anemia if not monitored.

Calcium and vitamin D absorption may also be reduced, increasing the risk of bone thinning over time. Regular screening, supplements, and sometimes bone density scans become part of long-term follow-up care.

Folate, zinc, and fat-soluble vitamins can also dip, depending on diet and absorption patterns. That’s why many patients work closely with a dietitian or nutritionist after surgery — not just to get enough calories, but to rebuild the body’s balance from the inside out.

Maintaining Weight and Strength

Weight loss is expected — especially after surgery. Some people drop 10, 20, even 30 pounds in the first few months. But not all weight loss is equal. What matters isn’t just pounds, but muscle mass, energy, and how the body functions day to day.

The goal is to stabilize weight, not necessarily to return to a pre-surgery number. Often, people settle into a new baseline — lighter, but still strong. Muscle-building foods like eggs, fish, poultry, and legumes become important, as do calorie-dense but easy-to-digest items like nut butters, smoothies, and soft dairy.

For those who struggle to eat enough by mouth, enteral feeding (via a feeding tube) may be used temporarily. This isn’t a failure — it’s a support, a bridge between surgery and recovery, especially when the appetite is slow to return.

Chemo and radiation can also impact appetite. Nausea, mouth sores, changes in taste — all of these make food less appealing. Sometimes the effort to eat feels bigger than the reward. But with time, and with help, most people find their way back to food again.

Building a New Relationship With Food

After stomach cancer, eating becomes something you pay attention to — not in fear, but in detail. You start to notice how certain foods affect your energy, how pacing changes your symptoms, how social meals feel different. You might find joy in simpler things — warm broth, plain rice, a soft piece of toast with butter — because they’re gentle and reliable.

Some patients journal their meals to spot patterns. Others build routines around breakfast and dinner, then improvise the rest. It’s a process of trial and error — and also of patience. You’re not just fueling the body anymore. You’re negotiating with it.

There’s also the emotional side. For people who once found comfort, celebration, or identity in food, this new relationship can be hard. Meals may feel smaller not just physically, but socially. That’s why support groups, counseling, or simply open conversations with family can make a difference.

Exercise, Energy, and Everyday Life

Physical activity is often encouraged — gently and gradually. Walking helps digestion. Light strength training preserves muscle. Movement supports circulation, mood, and sleep. But the body’s limits are different now, and it’s important to listen closely. Energy often comes in windows. Some days are better than others. That’s normal.

Work may be possible, depending on your job and recovery speed. Some people return after a few months; others take longer. What’s important is not rushing — not measuring progress against anyone else’s story, but against your own.

The Long Game

Living after stomach cancer is just that: living. It’s not about getting back to how things were. It’s about building something new — a body that works differently, a diet that adapts, a lifestyle that shifts with need and capacity.

Some people return to near-normal eating after a year. Others live with permanent changes — smaller meals, more supplements, a different sense of fullness. But almost everyone finds some rhythm again. Not perfect, but stable. And that’s enough.

Part Eleven: Frequently Asked Questions

Can a colonoscopy detect stomach cancer?

No — not directly. A colonoscopy only examines the large intestine (colon) and rectum. It doesn’t reach the stomach at all. Stomach cancer is diagnosed with a different procedure: an upper endoscopy, where a thin camera tube is passed down the throat to examine the esophagus, stomach, and the first part of the small intestine. If you’re having symptoms that might suggest a stomach issue — like persistent nausea, early fullness, unexplained weight loss, or anemia — your doctor might recommend an endoscopy instead of (or in addition to) a colonoscopy.

In rare, advanced cases where stomach cancer has spread far enough to invade the colon, a colonoscopy might detect those changes — but that’s not how it’s usually found.

Can a blood test detect stomach cancer?

Not reliably. There’s no standard blood test that can screen for or confirm stomach cancer in its early stages. Some tumor markers — such as CEA or CA 19-9 — may be elevated in patients with stomach cancer, but they aren’t specific, and they often remain normal even when cancer is present. These markers are more useful for tracking how the disease responds to treatment after a diagnosis is made, not for spotting the cancer early.

However, indirect clues in routine bloodwork — like chronic iron-deficiency anemia — can sometimes be a sign that prompts further investigation. If you’re consistently low on iron without a clear cause, your doctor may order an endoscopy to rule out slow internal bleeding from the stomach or intestines.

Does stomach cancer show up in blood tests?

It doesn’t “show up” the way something like diabetes or liver disease might. But blood tests can raise suspicion — for example, if someone has low hemoglobin, signs of malnutrition, or abnormal liver enzymes in the context of other symptoms. These findings don’t diagnose cancer, but they might lead to the right tests — especially endoscopy and imaging — that can.

In some cases, doctors may use tumor markers to track disease progression or recurrence after surgery, but not all patients produce these markers, and they’re never used alone to guide care.

If my sibling had stomach cancer, should I get a colonoscopy sooner?

Not specifically for stomach cancer. Since colonoscopy doesn’t examine the stomach, it won’t detect the kind of cancer your sibling had. But your family history still matters — and you may benefit from earlier screening via upper endoscopy, especially if your sibling was diagnosed at a young age (under 50), or if multiple family members have had stomach or related cancers.

In families with known hereditary conditions (like Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer or Lynch Syndrome), early and even preventive screening can make a life-saving difference. You may be eligible for genetic counseling and testing, especially if your sibling had a rare or aggressive form of cancer. If that testing reveals a relevant mutation, screening protocols — including both endoscopy and colonoscopy — may be recommended earlier than the general population.

What do stomach cancer CT images reveal?

A CT scan helps show how far the cancer has spread beyond the stomach. It won’t diagnose the cancer itself — that still requires a biopsy — but it plays a critical role in staging. CT images can reveal:

- A thickened stomach wall or mass

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Involvement of nearby organs (like the liver or pancreas)

- Fluid buildup in the abdomen (suggesting peritoneal spread)

- Distant metastases in the lungs or liver

CT is often the first imaging step after diagnosis and may be repeated throughout treatment to track response. It’s not infallible — small tumors can be missed — but it’s a cornerstone of modern staging and surveillance.

What’s chemotherapy like for stomach cancer?

Chemotherapy is used both before and after surgery, and also as a primary treatment if the cancer has spread. Most regimens involve a combination of drugs, typically including a fluoropyrimidine (like 5-FU or capecitabine), a platinum compound (like cisplatin or oxaliplatin), and sometimes docetaxel, trastuzumab (for HER2-positive cancers), or immunotherapy.

It’s usually given in cycles, with rest periods in between. The experience varies from person to person. Some patients feel mostly tired. Others deal with nausea, neuropathy, or appetite loss. The side effects tend to build over time, but so does the support. Antiemetics, nutrition advice, dose adjustments, and regular bloodwork monitoring are all part of standard care. For many, it’s hard — but manageable. And for some, it keeps the cancer stable for years.

What should I watch for after treatment ends?

Once treatment is over, monitoring for recurrence becomes the focus. This often includes regular follow-ups every few months, especially in the first two years. You and your doctor will watch for:

- New or returning symptoms (especially pain, fatigue, weight loss, or anemia)

- Changes on imaging scans

- Tumor markers, if they were elevated during your initial diagnosis

Recurrence is most likely to occur near the original site, in the lymph nodes, or in distant organs like the liver or peritoneum. If caught early, some recurrences are still treatable. If you’ve had stomach cancer, it’s important to stay in close touch with your care team, report new symptoms, and continue any nutritional follow-up as advised.

Closing Thoughts

Stomach cancer reshapes life at every stage — from symptoms that are easy to ignore, to treatments that ask everything of the body, to recoveries that take months to settle. Whether you’re still trying to understand a diagnosis, moving through chemotherapy, adjusting to life without a stomach, or quietly waiting for your next follow-up, this disease doesn’t follow a single story arc. It moves in real time, through decisions, doubts, waiting rooms, and small victories.

There’s no perfect roadmap for what comes next — only knowledge, choices, and support. And if you’re still searching for answers, you’re not behind. You’re already doing the work that matters most: paying attention, asking questions, staying engaged.